Abstract. The article presents the development of food retail in Poland in comparison with global trends, characterised by the tendency to replace small traditional food stores with large-format stores, such as supermarkets and hypermarkets. This tendency has led to the emergence of retail and food deserts in numerous countries. This is a major problem from the perspective of both practitioners and researchers. In Poland, like in many other countries in the world, similar processes in retail development occur, therefore, researchers should pay attention to the emergence of retail deserts, the so-called ‘supermarket deserts,’ as well as some limitations in terms of access to supermarkets. Many territorial units in Poland, especially in eastern Poland, have no large-format stores. These areas constitute retail deserts and require further micro-scale research.

Key words: food deserts, supermarket deserts, supermarket, hypermarket, marketisation, retail landscape, Poland

The growth of food retail, especially in developing countries, is characterised by the tendency to replace small traditional food stores with larger stores, such as supermarkets[1] and/or hypermarkets,[2] which is described in literature as the modernisation of food retail. On this basis, researchers began to identify food deserts and retail deserts. This research issue concerning commercially excluded areas is interdisciplinary in nature, as indicated by the interest in the topic not only among geographers, but also sociologists, economists, doctors, politicians, etc. This article focuses primarily on research regarding retail deserts in relation to supermarketisation and hypermarketisation, or phenomena that shape the modern retail landscape of Western European and Central European countries, including Poland. The name ‘food deserts’ is more suited to areas with no access or limited access to food, while ‘retail deserts’ describe areas which lack certain categories of retail facilities, e.g., supermarkets or hypermarkets. Obviously, in some cases, the lack of these forms of food stores does not have to cause a limited access to foodstuffs of appropriate quality and price.

An uneven expansion of food retail chains in a country can influence the emergence of retail deserts and food deserts, which may cause difficulties, such as a limited access to some shopping facilities. An uneven development of such individual facilities may lead to the emergence of retail or food exclusion for some social groups. According to M. C. Guy (1998, 2007), major issues include accessibility to shopping facilities and unjust treatment of marginalised social groups, for instance the elderly, the disabled, the unemployed, households with single parents, households with low income, or carless households.

The purpose of the article is to present the development of large-format food retail in Poland (hypermarkets and supermarkets) in comparison with global trends, especially those in Europe. The identification of analogical directions of changes makes it possible to predict further stages of development in this area of the Polish economy. In addition to numerical changes, the article also presents the spatial variation of the phenomenon in question in Poland.

The research on retail also includes studies on food deserts, which are quite extensive in English-speaking countries (USA, Canada, and the UK) but occasional and selective in some European countries (Germany, Sweden, and Slovakia). So far, Polish academic research has not raised the issue of food deserts which creates a peculiar research gap. Therefore, the additional purpose of this article is to raise awareness of the problem. The article focuses on presenting the trends in the development of large-format food retail in Poland and identifying areas where ‘trading deserts’ could potentially occur. The issue of such deserts is vital from both the practical and academic perspectives.

An in-depth analysis of the academic literature on retail deserts has been conducted mainly on the basis of English literature and statistical data from Statistics Poland (the data of Statistics Poland refers to the number of hypermarkets and supermarkets). The work utilises indices of phenomenon intensity (e.g., the number of people per one market in both supermarkets and hypermarkets), and indices of dynamics (e.g., the changes in the number of hypermarkets and supermarkets in Poland in 2008‒2020; the increase in the number of supermarkets in Poland in 2008‒2018 per powiats[3]).

The notion of a ‘food desert’ is a relatively broad one and has been defined in different ways. The term was coined in Scotland in the early 1990s (Cummins and Macintyre, 2002: 2115, 2002a: 436). Since then, researchers have been using the term in various ways. For instance, in their research, Hendrickson et al. (2006: 372) defined food deserts as “urban areas with 10 or fewer grocery stores and no stores with more than 20 employees.” Cummins and Macintyre (2002a: 436) have defined them as “poor urban areas where residents cannot buy affordable, healthy food.” The latter definition focuses on the type and quality of food instead of the number, type or size of food stores available to residents (Walker et al., 2010, p. 876). Guszak et al. (2016) reviewed the literature which defined and characterised a food desert. The term was used to describe areas with no food stores (Cummins and Macintyre 1999; Morton et al., 2005), areas with food stores located at a major distance from each other (Coveney and O’Dwyer, 2009; Donkin et al., 1999; Wrigley et al., 2004), areas with a poor selection of fresh and healthy products (Clarke, et al., 2002; Coveney and O’Dwyer, 2009; Gallagher, 2008; Wrigley et al., 2002), as well as areas whose residents have low incomes and therefore face difficulties in accessing suburban supermarkets, due to the lack of cars or non-existent or too expensive public transportation (Coveney and O’Dwyer, 2009; Laurence, 1997; Short et al., 2007). Food deserts are areas (urban or rural) with relatively disadvantageous social and economic conditions, where the problem of the lack of the means of transport increases and residents are unable to access stores located further away from home and find better retail food sources (e.g., supermarkets) (Apparicio et al., 2007; McEntee and Agyeman, 2010; Walker et al., 2010).

Studies on the occurrence of food deserts are reflected in practice. For instance, during the Australian census of 2001, residential housing was classified as being badly located in terms of access to healthy food, or as food deserts if the census district it was located in had a high percentage of carless households or the distance between the household and the closest supermarket exceeded 2.5 km (Coveney and O’Dwyer, 2009). In the USA, for an area to be classified as a food desert with poor access to foodstuffs, at least 500 people and/or 33% of people in the census must live further than a mile (approx. 1.6 km) from a supermarket or a large food store (in the case of the census in rural areas, the distance exceeded 10 miles, approx. 16 km) (Khalil and Mendelson, 2017; USDA, 2015; Ver Ploeg et al., 2011).

One theory on the emergence of food deserts in the USA was associated with both the development and closing of stores (Curtis and McClellan, 1995; Guy et al., 2004). It is believed that the development of a supermarket network influences the consumers’ access to food of better quality, higher diversity, and lower prices. The expansion of these large food stores located outside cities (or on their edges) resulted in the closures of smaller (independent) food stores. The areas where affordable diverse food is accessible only to people with cars or those willing to pay for public transport emerged.

This phenomenon may lead and does actually lead to the emergence of areas with limited access to diverse ‘healthy’ food. Generally, supermarkets have this type of food on offer at an affordable price. For this reason, some studies associate access to healthy food with access to a supermarket or a large food store. Because of such deliberations food deserts were defined as areas with limited access to healthy and affordable food (Apparicio et al., 2007; Jiao et al., 2012; Križan et al., 2015). Moreover, supermarkets have longer working hours, have better parking facilities, and are attractive to customers (Alwitt and Donley, 1997; Guy et al., 2004). Another approach assumes that the high competitiveness of supermarkets selling general products leads to defining a food desert as an area which creates a retail emptiness (Furey et al., 2001; Walker et al., 2010). This is due to the closure of small local stores which lose against supermarkets and hypermarkets.

Guy and David (2004, p. 223) have identified five characteristics of a food desert:

From the perspective of researchers, spatial access to large food stores and supermarkets is the precondition for buying and consuming healthy food (Farber et al., 2014). Neighbourhoods with poor spatial and economic access to such stores are colloquially named ‘food deserts’ (Jiao et al., 2012; Larsen and Gilliland, 2008; USDA, 2014). According to, for instance, Short et al. (2007), food deserts are places which converge the transport constraints of carless residents and a lack of supermarkets forcing residents to pay inflated prices for inferior and unhealthy food in small local markets and general food stores (Short et al., 2007, p. 352). There is also an uneven distribution of grocery shops and the presence of disadvantaged neighbourhoods with no access to supermarkets (Walker et al., 2010).

Since the mid-1990s, the concept of an urban food desert has been widely studied in the poor districts of European and North American cities. Food deserts are often characterised as areas with disadvantageous economic conditions, where access to healthy and affordable food is limited due to the lack of modern retail outlets (such as supermarkets) (Battersby and Crush, 2014, p. 143). Even households with cars may not always want to bear the associated fuel costs. In inner city neighbourhoods of developed countries such as the UK, USA, and Canada, the number of supermarkets and large food stores has decreased with only a few independent stores, small supermarkets or discount stores remaining.[4] These stores offer less diverse and cheaper selections of food (Larsen and Gilliand, 2008; Cummins and Macintyre, 2002; Wrigley, 2002). Access to such food is worse for certain groups and it is necessary for people to travel outside their neighbourhoods to purchase cheaper goods (Larsen and Gilliand, 2008). Such city centre neighbourhoods are defined as food deserts and they have become the subject of research on the identification of social exclusion and health-related inequalities in urban areas (Ozuduru, Guldman, 2013, pp. 5–6).

It should be remembered that high-quality food may be delivered by various suppliers, such as large-format supermarkets, corner stores and mobile food trucks, large-format grocery stores, and supermarkets (Block and Kouba 2006). Since spatial access is the precondition for buying and consuming healthy food, these studies focus on the spatial access to large grocery stores and supermarkets (Farber et al., 2014).

Particularly since the early 20th century, there have been some changes to the retail maps of individual countries. This was a result of the emergence of new formats of large-format commercial spaces such as supermarkets, hypermarkets, as well as shopping centres of various types and generations. The development of individual facilities was uneven and had different dynamics depending on the country. The term “supermarketisation” is sometimes used to describe the observed increase in the number and market percentage of the modern formats of food retail (e.g., Dries et al., 2004; Reardon et al., 2009).

As a result of the globalisation of the economy, the foreign expansion of trade tycoons has accelerated the process of the concentration of retail chains and resulted in the growing dominance of the biggest retailers in many countries. This expansion mostly applies to emerging markets: Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, South-East Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America (Kaczmarek, 2010).

The development of modern retail began in the 1930s in USA and soon after in Western Europe. Since the 1990s, this type of retail has become a global phenomenon, spreading throughout all the developing regions. Recognised retail chains from USA and Western Europe have grown on a global scale. At the same time, their business models have been adopted by local companies, many of which have managed to build enormous retail chains and even develop on the international scale. The driving force behind the globalisation of retail was the growing competitiveness between the retail chains from USA and Western Europe (Altenburg et al., 2016).

Reardon et al. (2003) have distinguished four waves of supermarket expansion, encompassing different regions and countries in the world. The first wave occurred in the early 1990s mainly in the countries of South America, parts of South-East Asia, Northern and Central Europe (Baltic states, Poland, and the Czech Republic), as well as Southern Africa. The second wave started in the mid-1990s and encompassed parts of South-East Asia, Latin America, South America, as well as Northern and Eastern Europe (e.g., Bulgaria). The third wave emerged in the mid-2000s – supermarkets spread to other parts of Central and South America, South-East Asia, China, India, Eastern Europe, and Russia. The fourth wave encompassed mostly the countries of Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.[5]

In the early and mid-1990s in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the supermarket revolution began (Reardon and Berdegué, 2006), fuelled mostly by foreign direct investments (FDIs) from renowned American and West European food store v chains (Altenburg et al., 2016). At that time (the mid-1990s) various stages of commercial development could be distinguished in Western Europe (Kłosiewicz and Strużycki, 1997):

During the times of the communist regime, Central and East European consumers bought the majority of food products in state-owned retail stores and cooperatives, as well as fresh produce in private shops and at farmers’ markets (fruit and vegetable markets). During the transition stage in the 1990s, the retail sector was privatised and supermarket chains with foreign and domestic capital began to emerge. All countries of Central and Eastern Europe have undergone the same three phases of retail transformations, with major differences in the time it took to transition from one phase to another. The first phase, i.e., “the communism era,” was the period prior to reforms. The second phase, i.e., “the transition phase,” was the first stage of transformation, wherein serious reforms took place, including the privatisation and liberalisation of the market. In the third phase, i.e., the “globalisation era,” large investments of international enterprises occurred in the retail sector. All countries of Central and Eastern Europe began the transition phase in 1989–1991. The subsequent phases were much more diverse. For instance, countries such as the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland were first wave countries in terms of retail transformation, with globalisation occurring circa 1996. Balkan states, such as Croatia, Romania, and Bulgaria, were part of the second wave, with globalisation of retail beginning in the late 1990s. In the third wave countries, including Russia and Ukraine, the globalisation of retail began only in 2002 (Dries et al., 2004).

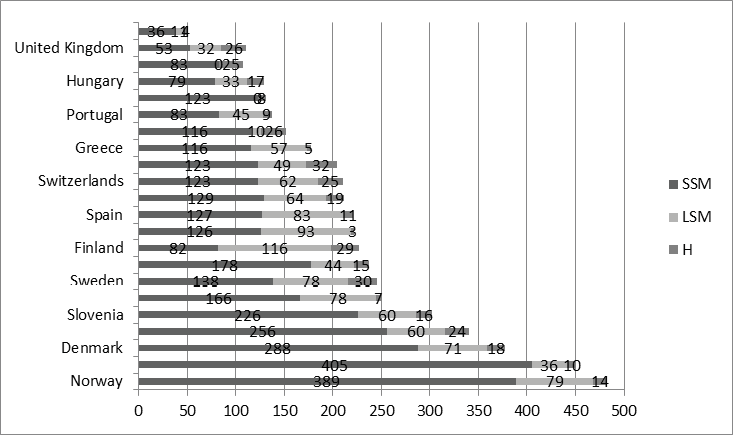

The structure of large-format stores in individual European countries is diverse as is the saturation of these retail facilities. On the one hand, there are countries with more than 450 large-format stores per million residents (Norway, Austria) and, on the other, countries with less than 150 such stores per million residents (Turkey, the United Kingdom, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Portugal) (Fig. 1). The list provided by Nielsen (2014) shows that Poland was a market with poor saturation of large-format shopping facilities, which brought on their intense development in the following years.

The natural decrease in retail selling area has resulted in a greater concentration of shopping facilities; currently, it is common that only 3‒4 biggest chains control as much as 90% of a market in a country (Geomarketing, GfK, 2017). Despite the facts presented above, further decreases in retail area per person are expected.

Fig. 1. The number of supermarkets and hypermarkets per 1 million of residents in European countries

SSM ‒ supermarkets (400‒1000 sq. m); LSM ‒ large supermarkets (1000‒2500 sq. m); H ‒ hypermarkets (>2500 sq. m) (Nielsen, 2014) Nielsen, 2014. GROCERY UNIVERSE 2014, Results of the 52nd inventory of retail grocery in Belgium, drawn up by Nielsen

Eastern markets still have some potential to obtain new retail areas. Some of the western chains took advantage of that in order to further their development (e.g., Auchan, Carrefour, the Delhaize Group or the Agrokor Group). Another new tendency is to introduce new concepts which offer customers a better sales culture and customer service, as well as more convenient shopping (usually Lidl, partially also Kaufland) (Kunc and Križan, 2018). In 2016, the retail landscape in individual countries was still diverse. Economies with minor retail trade, with less than 0.8 sq. m per resident (Ukraine, Romania, Bulgaria, and Greece) functioned right next to countries with a large surface area of more than 1.6 sq. m per resident (Austria, Belgium, and Netherlands) (Table 1).

Table 1. Retail selling area per person in 2016 in selected European countries (in sq. m)

| Country | Retail area (sq. m) | Country | Retail area (sq. m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 1.67 | Czech Republic | 1.04 |

| Belgium | 1.64 | Italy | 1.03 |

| Netherlands | 1.61 | Hungary | 1.02 |

| Switzerland | 1.47 | Slovakia | 1.01 |

| Germany | 1.44 | Poland | 0.95 |

| Sweden | 1.27 | Greece | 0.74 |

| France | 1.23 | Bulgaria | 0.74 |

| Spain | 1.12 | Romania | 0.70 |

| Croatia | 1.10 | Ukraine | 0.44 |

| Great Britain | 1.09 |

Source: REGIODATA research (2017): Regional economic data for Europe [online]. Available at: http://www.regiodata.eu/en/ [accessed on: 12.01.2022]; after: Kunc, J., Križan F., 2018, Changing European retail landscapes: New trends and challenges, Moravian Geographical Reports, 26 (3), p. 152.

One of the characteristic features of European retail trade is the possibility of distinguishing two types of its development, the so-called autonomous and colonised markets. Autonomous markets include: German, British, French, and Scandinavian markets. They have a relatively low presence of foreign chains and their native retail is somewhat specific, for instance the native hypermarket chain Carrefour predominates in France, while the discount chain Aldi is most popular in Germany. An unusually strong position of consumers’ cooperatives is typical of Scandinavian countries. Southern European markets (Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece) as well as Central and Eastern European markets fall into the second category of countries with a predominance of foreign retail chains (Ciechomski, 2010).

After the Second World War, in the Polish People’s Republic, in accordance with the law that considered state ownership the basis of the new political system, the so-called battle for retail was initiated midway through 1947. It largely led to the nationalisation of retail trade. In the 1950s and 60s, the construction of large-format department stores became widespread in Poland as one of the instruments in the struggle for trade. The stores included cooperative and common department stores, where state-regulated prices prevailed, and which were to serve as competition for private stores. However, these large-format forms could not be compared to modern markets and shopping centres constructed in other countries at the same time (different architecture, organisation, principles of functioning, and smaller surface areas ‒ the largest had surface areas of approx. 5,000 sq. m).

Polish retail trade began to undergo a dynamic transformations in the late 1980s. Initially, these changes involved only a dynamic growth in numbers resulting from establishing small private shops. As a consequence of these changes, Poland in the early 1990s saw a rapid increase in the number of stores opened by Polish entrepreneurs. Usually an owner established a single store, rarely – two or more. Traditional stores with small surface areas predominated. “Only between 1989 and 1991 did the number of stores in Poland increase more than twofold (from approx. 152,000 to 311,000)” (Cyrson and Kopczyński, 2016). The numbers continued to increase until 2008, when Statistics Poland registered more than 385,000 commercial facilities. Since then, the tendency has reversed, and a gradual decrease in the number of stores has been taking place. In 2020, only approx. 320,000 such shops were registered.

As a result of the growth in shop numbers, the Polish retail trade in the late 20th and the early 21st century was still largely fragmented. In 2003, there were approx. 12 stores per 1,000 residents. In comparison, in the same year this value was 7.8 in France, 6.2 in Sweden, 5.8 in the United Kingdom, 5.6 in Finland, and only 5.0 in Austria. However, it should be mentioned that Poland was not the only country with such a high dispersion of retail trade. In some European countries it was even higher: Portugal had 13.3 stores per 1000 residents, Italy 15.6, and Greece 17.4 (Cyrson and Kopczyński, 2016).

The 1989 political upheaval caused transformations to all sectors of the national economy, including significant changes to retail trade. Among other things, the Polish market was opened to foreign capital, including one investing in large-format trade. A poor saturation with shopping facilities and a lack of modern retail forms resulted in the new and unfamiliar shopping facilities (supermarkets, hypermarkets, and shopping centres) quickly gaining numerous supporters in the form of Polish consumers, which influenced their development to spiral. In the 1990s, a gradual increase in the wealth of an average Polish consumer occurred, lifestyle was becoming more consumerist, and car ownership increased (which significantly increased access to large-format stores). This encouraged foreign investors to establish new shopping facilities. Those and other factors also determined the development of modern forms of retail concentration, i.e., shopping centres.

In the first transformation years in Poland, there was no large national capital specialising in retail. The gap was filled by foreign capital in the form of direct investments. Foreign capital saw incentives to invest in large-format stores in the form of: favourable tax regulations, low prices of purchasing or leasing real estates, the availability of qualified workforce, as well as a large and absorptive market. Large-format stores developed rapidly also due to the experience of foreign retail companies with global reach, large capital, and modern management (Wrzesińska, 2008).

It has already been mentioned that in the early 1990s, foreign retail chains began to enter the Polish market with large-format stores, including facilities with fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG): supermarkets (e.g., Billa, Champion, and Rema 1000), discount stores (e.g., Plus, and Biedronka), and hypermarkets (e.g., Geant, Tesco, Carrefour, and E. Leclerc), but also specialist hypermarkets with non-food goods, such as IKEA, Nomi, and Obi. In 1990, the German company Billa (since 2001 known as Elea, taken over by the French Auchan) opened the first supermarket in Poland, while the Belgian chain Globi was the precursor of discount stores with its first shop established in Warsaw (owned by the French Carrefour since 2000). The German HIT was the first hypermarket established in Poland (in 1994), with all 13 stores taken over by the British Tesco in 2002.

J. Dawson and J. Henley (1999), among others, explained why Poland was so attractive to large shopping chains. They enumerated the following factors which attracted foreign retail investors: large internal market resulting from the demographic potential of the country, the increasing wealth of Poles, enthusiastic consumerist attitudes (similar to the habits of western post-industrial societies), stable macroeconomic conditions, and a low competitiveness of native capital in the 1990s.

Yet another crucial change in retail in the early 1990s was privatisation ‒ the number of stores owned by the state was decreasing, while the number of those owned by private entities was rising. In only 4 years, between 1989 (25,000) and 1993, the number of private stores tripled (Cyrson and Kopczyński, 2016). In 2003, there were as many as 456,000. In the following years the tendency reversed (394,000 in 2007). At the same time, the number of retail facilities owned by the public sector decreased drastically from 27,000 in 1989 to approx. 1,300 in 2007 (Gazdecki, 2009).

With the development of market economy, the nature of Polish retail has changed significantly. Aside from the already-mentioned changes associated with the radical increase in shopping facilities, privatisation of retail, and its internationalisation (the emergence of foreign chains), Szromnik (2001) has also mentioned the development of street-market retail, the strengthening of newly made connections between trade and industry, the modernisation of trade techniques and customer service procedures, and the implementation of merchandising experiences in retail.

Ciechomski formulated the model of selective development of retail trade in Poland as early as in 2010, predicting that within 10‒20 years the FMCG market would be dominated by the following forms of retail: large-format retail (modern shopping centres), delicatessen (supermarkets with premium grade goods), discount stores (shops based on the cost leadership strategy), neighbourhood stores (convenience stores), and internet retail (online retail with home delivery of highly processed food, substances and household goods) (Ciechomski, 2010).

Despite the existence of certain differences, especially the large percentage of small stores, in the early 21st century general European tendencies and trends were observed in Poland. This is largely due to the internationalisation and globalisation of Polish trade, including (Drzazga, 2016):

In Poland, in the first decade of the 21st century the percentage of stores with large selling areas (over 400 sq. m) increased rapidly. This was caused by a fast development of the network of supermarkets, discount stores, hypermarkets, and shopping centres, which mostly belonged to foreign retail companies with large capital. The first and the beginning of the second decade of the 21st century also saw an intensification in the internationalisation and globalisation of Polish retail. Polish retail became an expansion area for the largest global trade companies: the English Tesco Plc, the French Carrefour SA, and the German Metro Gruppe (Real, Media Markt, Saturn, and Makro Cash&Carry). Aside from the above-mentioned companies, which have remained the largest global retail companies for many years now, a major role in the internationalisation of Polish retail was also played by other foreign retail companies with large shopping chains, such as: Jeronimo Martins from Portugal, Groupe Auchan from France, and Rewe AG, Edeka Gruppe, Schwarz Gruppe, Aldi Gruppe, and Tengelmann Gruppe from Germany. The internationalisation and globalisation of Polish retail have significantly accelerated concentration in this economic area in the country (Drzazga, 2016).

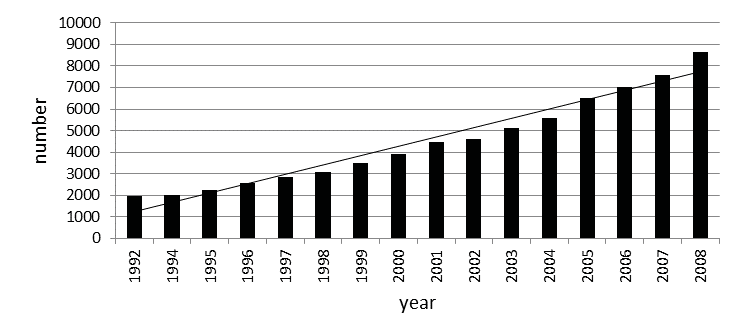

Between 1992 and 2008, the number of retail facilities with a surface area of 400 sq. m or higher increased from 1,973 to 8,634, so the absolute value of the increase amounted to 6,661 (Fig. 2), or 437.6%. The dynamics was the lowest between 1992 and 1994 with 101.1%, but it increased in the following years with an average annual value of approx. 111.1%.

Fig. 2. Changes in the number of stores with a surface area of 400 m2 in Poland in 1992‒2008

Source: M.Gazdecki, 2010, ‘Koncentracja handlu detalicznego w Polsce’, Journal of Agribusiness and Rural Development 2(16), Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego, Poznań. Dane pozyskane w oparciu Rynek wewnętrzny z lat 1991–2008. 2008. GUS, Warszawa.

In 2004, the method of classifying shops changed, with the largest divided into four groups in accordance to their surface area: 400‒999 sq. m, 1,000‒1,999 sq. m, 2,000‒2,499 sq. m, and with a surface area of ≥ 2500 sq. m. In terms of organisational forms, those are department stores,[7] trade houses,[8] supermarkets,[9] and hypermarkets.[10]

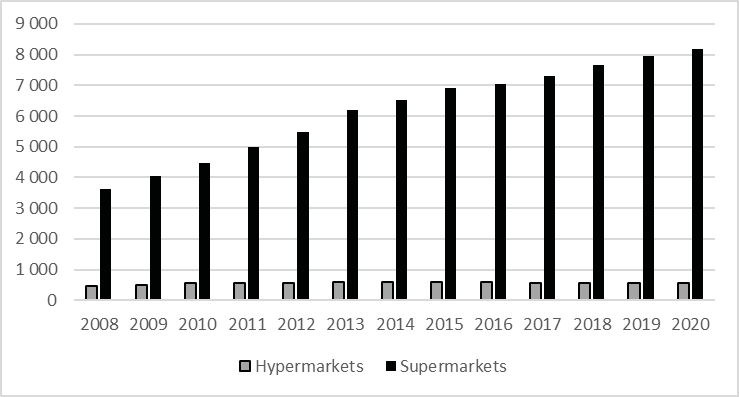

The first hypermarket in Poland opened in Warsaw in 1994. It belonged to the German chain HIT (taken over by Tesco in 2002). In the following years, other chains appeared. After several years of the predominance of small traditional stores, the expansion of large-format stores, especially hypermarkets, began. The upward trend in the number of hypermarkets lasted until 2014, but after that the trend reversed and decreases have been observed and the number has begun to decrease (546 in 2020).[11]

As Mazurkiewicz (2020) indicated, hypermarkets have continued to take the market by storm from the 1990s onwards. Polish chains were convinced that large stores with enormous assortments of goods would dominate the market. In Poland, the retreat from large areas in favour of smaller and medium-sized shops, but closer to home, is noticeable (Mazurkiewicz, 2020).

The situation is different with supermarkets, whose market continues to grow dynamically. In 2008, there were nearly 4,000 supermarkets in Poland, with twice as many (more than 8,000) in 2020 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Changes in the number of hypermarkets and supermarkets in Poland in 2008‒2020

Source: Own work on the basis of data provided by Statistics Poland

The spread of qualitatively new trading units has been uneven. The expansion of the biggest ones began in the largest cities and only later crossed into medium and smaller towns. Yet the location strategies of individual companies were diverse. Some focused on select regions of the country, others considered the sizes of settlement units and their consumerist or purchasing potential. Competitiveness also remained a major factor in the adopted location strategies. It should be remembered that the times when individual companies entered the Polish market differed, additionally there were changes in ownership that resulted in the process of rebranding and divestments[12] in retail.

After saturating large urban centres, retail chains began to expand to ever smaller centres, especially main cities of powiats that offered better potential for good sales. This saturation is reflected in a denser network of facilities and decreased distances between stores within a chain. Food discount stores are most often the driving force behind such investments, since they win the battle for their clients’ wallets. Those were initially facilities with a basic assortment and low prices, but due to the continuous development of their offers they became a predominant form of retail, similar to the concept of supermarkets (Nowakowska and Palicki, 2016). For several years now food retail has been saturated with hypermarkets, but supermarket and discount stores still continue to expand (Cyrson and Kopczyński, 2016).

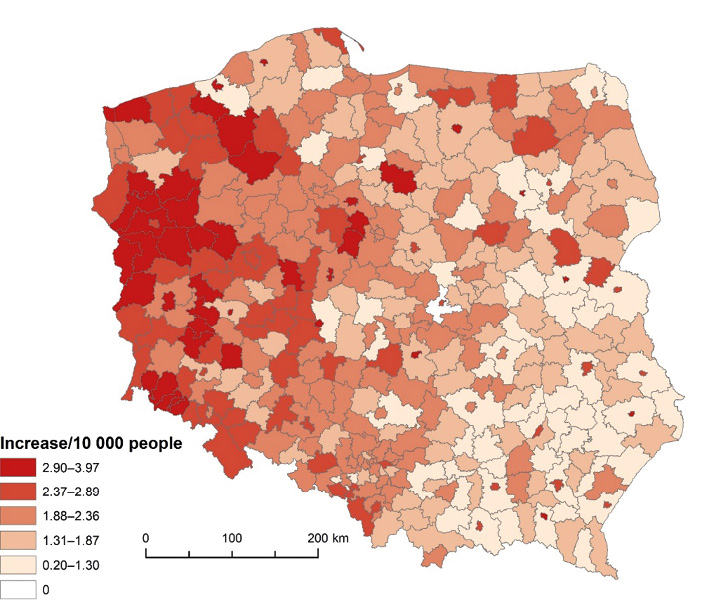

The development of supermarkets in the country (as seen in Fig. 4) is uneven. The greatest growth dynamics within the period of 10 years was observed in western Poland (even up to 4 stores per 10,000 people) in urban areas, in areas with the highest numbers of tourists, and in borderlands (the western border with Germany and partly also the southern border with the Czech Republic). The weakest development occurred in the south-eastern part of the country with less than 1.3 stores per 10,000 people (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Increase in the number of supermarkets in Poland in accordance with powiats in 2008‒2018

Source: own work.

The demand for goods and services offered in retail facilities is generated not only by local or domestic households, but also consumers from neighbouring countries. This is mostly visible in borderlands, where the residents of neighbouring countries frequent retail facilities more often than the residents of the country (city or region). This phenomenon is common in areas where well-developed and weaker economies meet. In case of the latter, both goods and services are competitive in terms of price. The differences in currency exchange rates are also favourable to shopping tourism (Foryś, 2014). In this case, obviously, the possibility of crossing the border is also a factor, due to such obstructions as, for instance, rivers.

For several years now, the tendency to shop in smaller-surface stores has been observed. There are numerous causes of this phenomenon. Discount stores (with smaller surface areas) gain significance and their percentage in the food market continues to grow. Poles perceive them as offering products with a good quality-to-price ratio. More and more often consumers also appreciate the comfort of shopping, choosing stores located closer to home, with no need for additional travel (Cyrson and Kopczyński, 2016, pp. 20–21).

In studies on food deserts some researchers consider the accessibility to supermarkets as facilities with a diverse, rich assortment, providing healthy and affordable food (e.g., Gay et al., 2004; Apparicio et al., 2007; Jiao et al., 2012; Battersby and Crush, 2014; Križan et al., 2015; Guszak et al., 2016).

The uneven expansion of food store chains in Poland (supermarkets and hypermarkets) may influence the appearance of food deserts and lead to the phenomenon of retail or food exclusion. The lack of such stores in some territorial units may foreshadow the appearance of food deserts there. In such areas, residents may have limited access to a diverse offer of goods, due to, for instance, transportation limits (no car or underdeveloped public transport), economic limits (travel expenses or prices of goods), assortment limitations (lack of retail facilities or small stores without a diverse offer), and health limitations (immobility or difficulty in getting around).

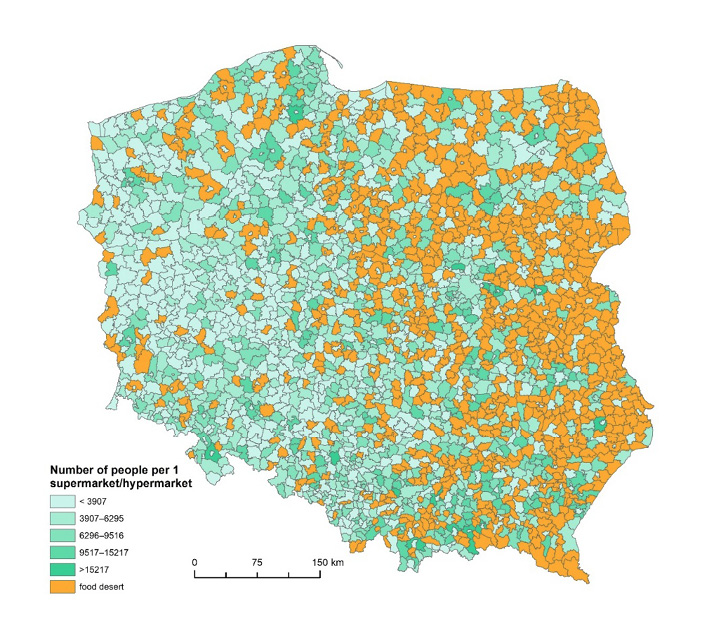

Figure 5 shows the number of residents per one supermarket or hypermarket in 2020 per administrative units. Many areas in Poland have no such forms of retail and are therefore categorised as potential food deserts. The highest number of units without these stores is in eastern Poland (the Lublin and Podlaskie Voivodeships), south-eastern Poland (the Subcarpathian Voivodeship) and north-eastern Poland (the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship). In territorial units with supermarkets and hypermarkets, their index is often relatively high, with more than 9.5000 residents per one shopping facility. The situation is different in the western part of the country (the Greater Poland and Lubuskie Voivodeships), south-western Poland (the Lower Silesian Voivodeship), north-western Poland (the West Pomeranian Voivodeship) and in southern Poland (the Silesian and Opole Voivodeships). Those areas have few units without supermarkets or hypermarkets, and there is more of them in places where they do exist than in eastern parts of the country, which translates into a lower number of residents ‒ often less than 3.9000 ‒ per one supermarket or hypermarket (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Number of people per one supermarket or hypermarket in Poland in 2020, per administrative units

Source: own work.

The unevenness of supermarketisation is the result of, among others, the varied levels of social and economic development in individual regions. Eastern areas are largely agricultural, with a lesser density of settlements, and residents with lower income. According to Statistics Poland, the average monthly gross income in relation to the national average (Poland = 100) in 2020 was the lowest in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship (85.2%) and the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship (85.3%). The highest was recorded in the Masovian Voivodeship (119.2), although it should be mentioned that it is the largest voivodeship in terms of surface area and contains the Warsaw Metropolitan Area, which boosts the index (which is lower in other parts of this administrative unit). The Lower Silesian Voivodeship (with its capital in Wrocław) also exceeds the value of 100, with 103.1. The differences in the level of social and economic development in Poland stem not only from the differences in environmental conditions, but also historical ones. For more than a century individual areas of the country functioned within different state organisms, during the Partitions of Poland. The eastern and central Poland was incorporated into Tsarist Russia (Russian Empire), the south-eastern Poland (the Subcarpathian Voivodeship) was incorporated into the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the remaining northern, western and southern areas were incorporated into Prussia. This long period in Polish history to this day impacts the distribution of numerous social and economic phenomena, in many cases showing the preservation of the borders from the era of the Partitions.

The role of national borders was mentioned when describing the dynamics of the development of supermarkets and hypermarkets. Poland is part of the European Union (EU), and therefore it is open in the south and west, allowing for the free crossing of borders. The difference in prices, mostly between Poland and Germany, results in increased shopping tourism in Poland, which contributes to the retail investors’ interest in these areas. That is why the number of units without supermarkets is low. The rivers Lusatian Neisse and the Oder constitute Polish borders, therefore, they are a barrier hindering the free crossing – the gminas[13] (communities) with no border checkpoints develop more weakly in terms of retail. Eastern and northern Polish borders are simultaneously the borders of the EU with Ukraine,[14] Belarus, and Russia which means there are regulations in place when it comes to crossing them. Additionally, the purchasing power there is weaker and the prices are lower. For these reasons, eastern areas are less attractive to investors in search of locations for future supermarkets and hypermarkets.

When it comes to the retail landscape, urban areas are highly attractive to investors, for example the Warsaw Metropolitan Area, the Gdańsk Metropolitan Area, the Bydgoszcz–Toruń Metropolitan Area, areas with high urbanisation, such as Upper Silesia or tourist locations (mainly mountain towns and the Masurian Lake District).

The research on the locations of food deserts considering only supermarkets and hypermarkets is based on a significant simplification. Areas without such objects do not necessarily constitute a retail desert with limited access to grocery stores offering a non-diverse assortment of goods.

Subject literature seems to confirm such observations. For instance, Ver Ploeg (2011) has claimed that the lack of access to supermarkets does not necessarily mean the access to products is limited, since they can be purchased in other food stores, such as ethnic stores, specialist stores, and markets. Rose et al. (2009) discovered that certain districts (e.g. Village de L’Est, Treme in New Orleans) identified in some studies as food deserts due to the lack of supermarkets could not be considered food deserts, since they had many smaller stores with basic food products.

A state-wide research involving only access to supermarkets and hypermarkets identifies areas where residents have potentially limited access to numerous products. Such analyses should be continued on the microscale and they should consider other retail units to verify the presence of food deserts.

On the global scale, supermarkets and hypermarkets are the predominant form of food retail, and in developed economies they have the highest percentage in total sales. In USA, hypermarkets constitute the basic form, but in Western Europe, where urban areas are more densely populated, the space is limited, more people use public transport and there are greater physical limitations to constructing large-format stores (e.g., supermarkets, hypermarkets). Additionally, many regulatory authorities in Europe prohibit the construction of large stores in central locations.

In some countries, especially in Germany, the United Kingdom and USA, hypermarkets and supermarkets are put under pressure by discount stores which develop rapidly and take over many customers of traditional supermarkets. Discount stores offer a cheap, limited and standardised assortment of articles, which lowers their costs (Acker, 2011; Jürgens, 2011).

The emergence of new forms of retail on the Polish market has had an impact on its retail map. The changes have involved a major decrease in retail facilities, which may suggest that numerous stores did not meet the challenge of competing with new retail forms and/or failed to adapt to the new retail reality and meet consumers’ expectations. Retail in Poland has also been influenced by an increase in consumer mobility (higher level of car ownership). Some customers were no longer dependent on the location of stores or the availability of public transport. New types of retail facilities had car parks and favourable locations (near transport routes with high traffic capacities), thus becoming attractive to customers. Their attractiveness was further increased through their assortment of goods and their competitive prices, reinforced by numerous special offers.

As it has already been indicated, the development of retail in Poland is similar to that in other parts of the world. In particular, supermarkets, and discount and convenience shops are gaining in importance. This trend in many places may, on the one hand, facilitate access to groceries, but, on the other, it leads to the closure of small local shops. The purpose of the article was not only to present the tendencies in the development of large-format stores in the era of globalisation and internationalisation, but also to identify potential areas of retail exclusion. The research conducted has shown that areas less saturated with such shops are located in the east and south-east of Poland. A more detailed identification of areas in Poland that are in danger of becoming trade deserts may become a valuable tip for investors in food retail, both foreign and – perhaps above all – domestic.

ALTENBURG, T., KULKE, E., REEG, C., PETERSKOVSKY, L. and HAMPEL-MILAGROSA, A. (2016), Making retail modernisation in developing countries inclusive: a development policy perspective, Discussion Paper, 2, Bonn: Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik, German Development Institute.

ALWITT, L. F. and DONLEY, T. D. (1997), ‘Retail Stores in Poor Urban Neighborhoods’, The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 31 (1), pp. 139–164.

APPARICIO, P., CLOUTIER, M.-S. and SHEARMUR, R. (2007), ‘The case of Montrèal`s missing food deserts: evaluation of accessibility to food supermarkets’, International Journal of Health Geographics, 6, 4.

BATTERSBY, J. and CRUSH, J. (2014), ‘Africa’s Urban Food Deserts’, Urban Forum, 25, pp. 143–151.

BATTERSBY, J. and CRUSH, J. (2014, June), ‘Africa’s urban food deserts’, [in:] Urban Forum, 25 (2), pp. 143–151. Springer Netherlands.

BEHJAT, A., KOC, M. and OSTRY, A. (2013), ‘The importance of food retail stores in identifying food deserts in urban settings’, WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, 170, pp. 89–98.

BLOCK, D. and KOUBA, J. (2006), ‘A comparison of the availability and affordability of a market basket in two communities in the Chicago area’, Public Health Nutrition, 9 (07), pp. 837–845.

CIECHOMSKI, W. (2010), Koncentracja handlu w Polsce i jej implikacje dla strategii konkurowania przedsiębiorstw handlowych, Poznań: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego.

CLARKE, G. EYRE, H. and GUY, C. (2002), ‘Deriving Indicators of Access to Food Retail Provision in British Cities: Studies of Cardiff, Leeds and Bradford’, Urban Studies, 39 (11), pp. 2041–2060.

COVENEY, J. and O’DWYER, L. A. (2009), ‘Effects of Mobility and Location on Food Access’, Health and Place, 15 (1), pp. 45–55.

COVENEY, J. and O’DWYER, L. A. (2009), ‘Effects of Mobility and Location on Food Access’, Health and Place, 15 (1), pp. 45–55.

CUMMINS, S. and MACINTYRE, S. (1999), ‘The Location of Food Stores in Urban Areas: A Case Study in Glasgow’, British Food Journal, 101 (7), pp. 545–53.

CUMMINS, S. and MACINTYRE, S. (2002), ‘A Systematic Study of an Urban Foodscape: The Price and Availability of Food in Inner Glasgow’, Urban Studies, 39 (11), pp. 2115–2130.

CUMMINS, S. and MACINTYRE S. (2002a), ‘Food deserts – evidence and assumption in health policy making’, British Medical Journal, 325, pp. 436–438.

CURTIS, K. and MCCLELLAN, S. (1995), ‘Falling through the safety net: poverty, food assistance and shopping constraints in an American City’, Urban Anthropology, 24, pp. 93–135.

CYRSON, E. and KOPCZYŃSKI, T. (2016), Trzy dekady handlu. Kształtowanie się polskiego rynku na przykładzie sieci Żabka, Wyd. Edward Cyrson, Tomasz Kopczyński.

DAWSON, J. and HENLEY, J. (1999), ‘Internationalisation of Retailing in Poland: Foreign hypermarket development and its implications’, [in:] The Internationalisation of Retailing in Europe, K. Centre for the study of Commercial Activity-Ryerson Polytechnic University, Canada, pp. 22–27.

DONKIN, A. J. M., DOWLER, E. A., STEVENSON, S. J. and TURNER, S. A. (1999), ‘Mapping Access to Food at a Local Level’, British Food Journal, 101 (7), pp. 554–564.

DRIES, L., REARDON, T. and SWINNEN, J. F. (2004), ‘The rapid rise of supermarkets in Central and Eastern Europe: Implications for the agrifood sector and rural development’, Development Policy Review, 22 (5), pp. 525–556.

DRZAZGA M., 2016, ‘Ewolucja form handlu detalicznego na początku XXI wieku’, Handel Wewnętrzny, 3 (362), pp. 114–125.

FARBER, S., MORANG, M. Z. and WIDENER, M. J. (2014), ‘Temporal variability in transit-based accessibility to supermarkets’, Applied Geography, 53, pp. 149–159.

FORYŚ I., 2014, ‘Obiekt handlowy w przestrzeni miejskiej’, [in:] FORYŚ, I. (ed.) Zarządzanie nieruchomościami handlowymi, Warszawa: Wyd. Poltext, pp. 45–104.

FUREY, S., STRUGNELL, C. and MCILVEEN, H. (2001), ‘An investigation of the potential existence of «Food Deserts» in rural and urban areas of Northern Ireland’, Agriculture and Human Values, 18, pp. 447–457.

GALLAGHER, M. (2008), Food Desert and Food Balance Indicator Fact Sheet, Chicago: Mari Gallagher Research and Consulting Group, http://www.marigallagher.com/site_media/dynamic/project_files/FdDesFdBalFactSheetMG_.pdf [accessed on: 11.09.2015].

GAZDECKI, M. (2009), ‘The restructuring and internalization of retail trade in Poland between 1990 and 2007’, Journal of Agribusiness and Rural Development, 11 (1), pp. 53–62.

Geomarketing (2017), European retail in 2017, GfK.

GUSZAK CEROVEČKI I., GRÜNHAGEN M. (2016), ‘«Food Deserts» in Urban Districts: Evidence from a Transitional Market and Implications for Macromarketing’, Journal of Macromarketing, 36 (3), pp. 337–353.

GUY, C. M., DAVID, G. (2004), ‘Measuring physical access to ‘healthy foods’ in areas of social deprivation: a case study in Cardiff’, International Journal of Consumer Studies, 28 (3), pp. 222–234.

GUY, C., CLARKE, G., EYRE, H. (2004), ‘Food retail change and the growth of food deserts: a case study of Cardiff’, International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management 32 (2), pp. 72–88.

GUY, C. M. (1998), ‘Controlling new retail spaces: the impress of planning policies in western Europe’, Urban Studies, 35 (5–6), pp. 953–979.

GUY, C. M. (2007), Planning for Retail Development, New York: Routledge.

GUY, C. M. and GEMMA D. (2004), ‘Measuring Physical Access to «Healthy Foods» in Areas of Social Deprivation: A Case Study in Cardiff’, International Journal of Consumer Studies, 28 (3), pp. 222–234.

HENDRICKSON, D., SMITH, C., EIKENBERRY, N. (2006), ‘Fruit and vegetable access in four low-income food deserts communities in Minnesota’, Agriculture and Human Values, 23, pp. 371–383.

JIAO, J., MOUDON, A. V., ULMER, J., HURVITZ, P. M. and DREWNOWSKI, A. (2012), ‘How to identify food deserts: measuring physical and economic access to supermarkets in King County, Washington’, American Journal of Public Health, 102, pp. 32–39.

KACZMAREK, T. (2010), Struktura przestrzenna handlu detalicznego. Od skali globalnej do lokalnej, Poznań: Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

KHALIL, H., MENDELSON, R. (2017), ‘Food deserts: where nutrition meets inequality’, [in:] Washington University Political Review, 19. http://www.wupr.org/2017/12/19/food-deserts-where-nutrition-meets-inequality/ [accessed on: 27.10.2020].

KLOSIEWICZ, U. and STRUZYCKI, M. (1997), Europejskie prawidłowości rozwoju handlu w Polsce, Handel Wewnętrzny, 43 (1), pp. 1–7.

KRIŽAN, F., BILKOVÁ, K. and KITA, P. and HORŇÁK, M. (2015), ‘Potential food deserts and food oases in a post-communist city: Access, quality, variability and price of food in Bratislava-Petržalka’, Applied Geography, 62, pp. 8–18.

KUNC, J. and KRIŽAN F. (2018), ‘Changing European retail landscape: New trends and challenges’, Moravian Geographical Reports, 26 (3), pp. 150–159.

LARSEN, K. and GILLIAND, J. (2008), ‘Mapping the evolution of „food deserts” in a Canadian city: supermarket accessibility in London, Ontario 1961–2005’, International Journal of Health Geographics, 7 (16).

LAURENCE, J. (1997), ‘More Equality – Just What the Doctor Ordered,’ The Independent, 11 June, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/more-equality-just-what-the-doctor-ordered-1255340.html [accessed on: 29.03.2015].

MARGHEIM, J., The Grocery of Eating Well. http://pdx.edu/ sites/www.pdx.edu.ims/files/media_assets/ims_mscape07atlas.pdf [accessed on: 15.01.2022]

MAZURKIEWICZ, P. (2020), ‘Nie ma nadziei dla hipermarketów’, Rzeczpospolita, 10 (14.01.2020), pp. A20–21.

MCENTEE, J. and AGYEMAN, J. (2010), ‘Towards the development of a GIS method for identifying rural food deserts: geographic access in Vermont’, USA. Applied Geography, 30 (1), pp. 165–176.

MORTON, L. WRIGHT, E., BITTO, A., OAKLAND, M. J. and SAND, M. (2005), ‘Solving the Problems of Iowa Food Deserts: Food Insecurity and Civic Structure’, Rural Sociology, 70 (1), pp. 94–112.

NEUMEIER, S. and KOKORSCH, M. (2021), ‘Supermarket and discounter accessibility in rural Germany– identifying food deserts using a GIS accessibility model’, Journal of Rural Studies, 86, pp. 247–261.

NIELSEN, A. C. (2014), Grocery Universe 2013, AC Nielsen, Brussels, http://be. nl. nielsen. com/trends/documents/GROCERYUNIVERSE2013Brochure. pdf [accessed on: 15.08.2014].

NOWAKOWSKA, K. and PALICKI, S. (2016), ‘Nieruchomości handlowe jako czynnik ożywiania przestrzeni małych miast’, Biuletyn Stowarzyszenia Rzeczoznawców Majątkowych Województwa Wielkopolskiego, 2 (46), pp. 107–115.

OSBERT-POCIECHA, G. (1998), ‘Dywestycje w przedsiębiorstwie’, Monografie i Opracowania, nr 126, Prace Naukowe Akademii Ekonomicznej im. Oskara Langego, 794, Wrocław.

OZUDURU B. H. and GULDMANN J. M. (2013), ‘Retail location and urban resilience: towards a new framework for retail policy’, Surveys And Perspectives Integrating Environment&Society, 6 (1), Resilient Cities, https://journals.openedition.org/sapiens/1620 [accessed on: 20.01.2021].

PAJERSKÁ, E. (2016), ‘Food deserts as a consequence of modernization of food retail’, Acta Oeconomica Cassoviensia, IX (1), pp. 68–80.

REARDON, T., BARRETT, C. B., BERDEGUE, J. A. and SWINNEN, J. F. (2009), ‘Agrifood industry transformation and small farmers in developing countries’, World Development, 37 (11), pp. 1717–1727.

REARDON, T., TIMMER, C. P., BARRET, C. B. and BERDEGUÉ, J. (2003), ‘The rise of supermarkets in Africa, Asia and Latin America’, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 85 (5), pp. 1140–1146.

SHORT, A., GUTHMAN J. and RASKIN, S. (2007), ‘Food Deserts, Oases or Mirages? Small Markets and Community Food Security in the San Francisco Bay Area’, Journal of Planning Education and Research, 26 (3), pp. 352–364.

SHORT, A., GUTHMAN, J. and RASKIN, S. (2007), ‘Food Deserts, Oases or Mirages? Small Markets and Community Food Security in the San Francisco Bay Area’, Journal of Planning Education and Research, 26 (3), pp. 352–364.

SZROMNIK, A. (2001), ‘Dylematy zmian strukturalnych w handlu w Polsce na przełomie wieków’, Handel Wewnętrzny, 47 (2), pp. 14–25.

United States Department of Agriculture (2015). USDA defines food deserts, 04.04.2018. http://americannutritionassociation.org/newsletter/usda-defines-food-deserts [accessed on: 20.01.2022].

Ver PLOEG, M., NULPH, D. and WILLIAMS, R. (2011), Mapping food deserts in the United States, 27.10.2020. https://www.indicters.usda.gov/amber-waves/2011/december/datafeature-mapping-food-deserts-in-the-us/ [accessed on: 25.01.2022].

Ver PLOEG, M., NULPH, D., WILLIAMS, R. (2011), Mapping food deserts in the United States, 27.10.2020. https://www.indicters.usda.gov/amber-waves/2011/december/datafeature-mapping-food-deserts-in-the-us/ [accessed on: 23.01.2022].

WALKER, R. E., KEANE, C. R. and BURKE, J. G. (2010), ‘Disparities and access to healthy food in the United States: a review of food deserts literature’, Health Place, 16 (5), pp. 876–884.

WRIGHT, M. L., BITTO, E. A., OAKLAND, M. J. and SAND, M. (2005), ‘Solving the Problems of Iowa Food Deserts: Food Insecurity and Civic Structure’, Rural Sociology, 70 (1), pp. 94–112.

WRIGLEY, N. (2002), ‘«Food deserts» in British cities: policy context and research priorities’, Urban Studies, 39 (11), pp. 2029–2040.

WRIGLEY, N., WARM, D., MARGETTS, B. and LOWE, M. (2004), ‘The Leeds «Food Desert» Intervention Study: What the Focus Groups Reveal’, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 32 (2), pp. 123–136.

WRZESIŃSKA, J. (2008), ‘Rozwój wielkopowierzchniowych obiektów handlowych w Polsce’, Zeszyty Naukowe SGGW w Warszawie. Ekonomika i Organizacja Gospodarki Żywnościowej, 72, pp. 161–170.