Abstract. The aim of this article is to provide a holistic presentation of the genesis, intensity, and directions of movement, as well as the spatial and temporal distribution of the German national group which settled in Central Poland from the end of the 18th century to the 1820–1830 period. This paper analyses the determinants of the inflow of German immigrants, and their geographical origin, as well as the social and occupational structure. The settlers from German lands were a very diverse social group. In the case of first and second-generation immigrants who came to Central Poland, the social integration process was still quite slow. The colonists and settlers living in the diaspora developed a certain pattern of existence that focused on their immediate environment separating them from the outside world, while the retention of their mother tongue and religious tradition was more an expression of traditionalist consciousness than national identity.

Key words: German settlement in Poland, Central Poland, Łódź province, geography and history of migration.

The theme of German settlement in Poland has been the subject of numerous publications authored by Polish and German historians. The reasons and circumstances surrounding migratory movements have been discussed at length, yet little attention has been given to the spatial aspects of the phenomenon. Information regarding the directions of migration and locations of exile and settlement which appeared in texts devoted to Germans arriving in Polish territories provided merely a cursory view into the demographic, social, and settlement spatial structures of the German minority in Poland which took shape in the 19th century.

The purpose of this paper is to provide a more holistic presentation of the genesis, intensity, and directions of movement, as well as the spatial and temporal distribution of the German national group which settled in Central Poland from the end of the 18th century to the 1820–1830 period.[1]

Fig. 1. Administrative division of Central Poland from 1816 to 1938 and since 1999 onwards

Source: own work.

The assumed spatial scope of this paper basically covers the territory of Central Poland. State borders and internal administrative divisions of the Polish territories underwent multiple changes since the partitions. The notion of Central Poland, which has been gaining significance in scientific literature, is in principle equivalent to the Łódź region. In this study, the regional scope is defined by the borders of today’s province (voivodeship) of Łódź, supplemented by the areas of several counties (poviats) belonging to the province before World War II[2], and currently located in the province of Greater Poland (Wielkopolska) (see Fig. 1).

German settlement and the related processes of cultural permeation and transfer of new models and values to Poland date back to the Middle Ages. For centuries, Germans inhabited Poznań, Pomerania, and Upper Silesia, creating more or less tightly knit ethnic groups. The processes of medieval German colonisation also left their mark in Central Poland. Waves of the first emigrants from the shores of the Rhine River headed towards the poorly developed lands in the basin of the Warta and Vistula rivers.[3] The migrants who settled in Central Poland in the Middle Ages gradually became assimilated and in time completely Polonised. By the 16th century, the German minority in Polish cities was relatively small (Inglot, 1945, p. 64).

An influx of German settlers to Poland was noted during the Reformation, brought about by increasing religious persecution in the western part of the continent; meanwhile, the territory of what was then the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth enjoyed religious and national tolerance. In the 17th century, Hollander settlements quickly spread to the wetlands in the Vistula valley, on to Greater Poland and other parts of the country, including what is now the region of Central Poland. Initially, native Mennonites, the Dutch, Flemish, and Frisians were the prevailing immigrant groups, which gradually became Germanised. In the decades that followed, the ethnic composition of the settlers changed and ever so often the villages in the river valleys were settled by migrants originating mainly from northern Germany. Hollanders of German nationality[4] who came to the territory of Central Poland in the 18th century also originated from Brandenburg, West Pomerania, Saxony, Greater Poland, and Silesia. The destruction of Germany caused by the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) further intensified migration movements. The depopulation of Polish lands caused by numerous wars with Sweden, Russia, and Turkey also contributed to the influx of migrants from beyond the western border. Many villages were devastated, and the population was decimated by numerous plagues. As a consequence, areas which were previously cultivated for agriculture remained undeveloped. The development of Hollander settlements was one of the remedies to this situation.

Some time later, an influx of German people to Polish cities was noticeable. One of the several new urban centres that appeared in Central Poland in the first half of the 18th century was Władysławów, whose owner brought weavers from Bohemia and Saxony.[5]

German colonisation, which was spontaneous until the mid-18th century, significantly increased towards the end of the 1700s. In German territories, the concentration of land ownership in the hands of large owners and the economic stratification of peasants was becoming ever more visible. Living conditions in the overpopulated German territories became more and more difficult for the poorer population (Śladkowski, 1969, p. 118). At the same time, in the less populated Polish territories, economic development processes were initiated, which, in the absence of qualified personnel and capital, required support from the outside.

In the second half of the 18th century, the growing influx of economic immigrants to Poland from Germany mainly concerned agricultural colonists, who in particular headed in great numbers to the economically underdeveloped territory of Central Poland. This settlement intensified in the final two decades of the 18th century, when many new settlements were established in royal and private estates, inhabited by a German-speaking immigrant population. Quite often, the goal of the colonisation process was to restore economic functions to abandoned land, which had been excluded from use for many years. Yet in most cases, the Hollander villages in Central Poland were created ‘from scratch’, in areas not previously subject to settlement expansion.

The Hollander economy was definitely a cut above the economy of the serfs. It had greater efficiency, and the surplus production was sent to the market, contributing to the development of trade contacts between the country and the city. The inflow of German colonists in the pre-industrial era, both to rural areas and to cities, had substantial civilisational and cultural significance. It enriched Polish culture with new models that proved key for social and economic development and left their mark in many areas of life.

The second partition of Poland in 1793 meant that nearly the entire area of today’s Central Poland was within the borders of the Prussian state. A new province called South Prussia was created on the seized lands. The Prussian authorities introduced a number of legal regulations that were key for the relocation of the German population to the occupied territories. A decision was made to secularise church property and nationalise royal lands. Frederick William III ordered the development of colonisation plans for each of the provinces. That in turn paved the way to yet another stage of the inflow of German settlers to Central Poland (Breyer, 1941, p. 47). Meanwhile, Hollander settlement continued to develop in private estates (see Woźniak, 2013, pp. 96–99).

The Prussian colonisation was a de facto continuation of the settlement processes related to the Hollander colonisation during the pre-partition period[6]. The initial efforts were geared towards populating abandoned peasant farms. With time, the settlement campaign organised by the Prussian administration included the former estates of the Polish treasury. German peasants were also placed in noble estates repossessed for debts. The settlement of Polish lands with German settlers was connected to the implementation of the economic and political goals set by the Prussian government, while the goal of the spatial redistribution of the German population was to bring East Prussia and German Silesia closer together.

In 1798, a large-scale campaign was launched to encourage the inhabitants of the crisis-stricken region of Baden and Württemberg to migrate to sparsely populated South Prussia (see Woźniak, 2013, pp. 80–81). The Prussian government also tried to recruit settlers from Mecklenburg, taking advantage of the fact that in this region, from which fugitive peasants had long been migrating to Poland, the action of ousting peasants from their land was intensifying (Nichtweiss, 1954, pp. 122–127; Pytlak, 1917, p. 9). The authorities provided all peasants settling in South Prussia with significant allowances and financial aid; each settler was reimbursed for travel expenses and granted several years’ exemptions from taxes and military service (Smoleński, 1901, p. 214).

In the first period, settlers headed mainly to the Poznań region, and only a handful reached the Hollander villages in the Łódź region (Woźniak, 1993, p. 120). An organised and more massive influx of German settlers to Central Poland began in 1800. These were farmers, coming mainly from Württemberg, but also from Baden, Prussia, Bavaria, Neumark, Bohemia, and the Poznań region. The newcomers settled in existing villages or in newly established settlements.

Gradually, owners of private estates joined the government’s initiative to bring in colonists. Among the immigrants there were also handicraft weavers who founded the first textile settlements in Central Poland. In the years that followed, groups of new settlers increasingly included migrants from the south-western territories of Germany (Swabia, or, specifically, Baden, Hesse, Palatinate, and Württemberg). The new settlers were exempt from any payments, with the exception of rent paid after 3–6 years.

The greatest intensification of the Prussian colonisation campaign was between 1801 and 1806. This settlement activity indeed contributed to the economic revival of areas where new settlements were concentrated. German settlement in the Prussian period was essentially of an agricultural nature (although glassworks were also being established in many places) (Friedman, 1933, p. 115) despite the fact that settlers coming to cities could also count on the support of the Prussian government, including the reimbursement of travel costs, exemption from taxes and military service, and possibly a grant to open a workshop (see Smoleński, 1901, p. 215). Dąbie was the only town in Central Poland where, by dint of the influx of German craftsmen, cloth-making was developing on a larger scale since 1798 (see Friedman, 1933, p. 98).

Wąsicki estimates that between 1793 and 1806, around six thousand rural colonists settled in South Prussia on an area of 15,900 hectares (Wąsicki, 1953, pp. 137–179; 1957). Much larger numbers were cited by Z. Kaczmarczyk, who wrote that 13,800 people settled in South Prussia, of which 5,500 inhabited cities (Kaczmarczyk, 1945, p. 182). Other data claims that between 1802 and 1804 alone, 7,500 people migrated to South Prussia from German lands (Simsch, 1983, p. 222 et seq.).

At the end of the Prussian period (including earlier pre-1793 settlement), the Łódź region had a total of 14,200 farms situated in over 300 German settlements (referred to as ‘Swabian’ settlements, i.e., ‘Schwabensiedlungen’) inhabited by around 83,000 people (Heike, 1979, pp. X–XI). The settlements located in Central Poland were dominated by people from Swabia and Upper Franconia. The share of immigrants from Pomerania was quite significant, as it exceeded 1/3, while about 8% of the settlers came from Baden and Württemberg (Heike, 1979, p. IX).

As a result of military operations led in Poland in 1806 and 1807 and the loss of property, as well as the agitation of the Russian government, some settlers decided to migrate further east. Colonists who inhabited the areas that were most damaged during the war of 1807 were the most economically solid group of the peasantry, yet they became unable to meet their obligations to the Court and State, so they would sell their livestock and real estate for next to nothing and move to Russia, where they were given better conditions and were allotted large areas of land (cf. Mencel, 1959, pp. 136−137).

The establishment of the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807 (inhabited by over 10,000 German settlers who came there during Prussian and Austrian rule (Pytlak, 1917, p. 19)), which remained in union with the Kingdom of Saxony, brought about further economic development. The government of the Duchy continued earlier policies favouring the inflow of foreigners (Zdzitowiecki, 1948, pp. 428−430), mainly professionals, craftsmen, and farmers. Despite numerous incentives, the influx of new immigrants was limited and textile production in Central Poland remained underdeveloped. Yet the policy of the government was met with some interest from certain private landowners who took actions to settle German clothmakers.

The period of the Duchy of Warsaw brought a new stage in the colonisation of rural areas – the settlement campaign planned by the Prussian government was replaced by a spontaneous and rapid influx of German peasants to Central Poland. Additional farming colonies were established or existing ones expanded, and then settled by the German population, mainly in private estates, while the inflow of settlers to state-run estates was much weaker.[7]

Some of the settlers, who did not manage to establish themselves in their new homes as the end of their rent-free period was approaching, decided to leave the newly inhabited settlements and emigrate further. Napoleon’s defeat in the war with Russia and the years of the Russian occupation (1813–1815) resulted in the migration of an unknown number of German settlers to regions located deep in the Romanov empire. As a result of the recruitment campaign organised by the Russian authorities to encourage migration to the territory of the Empire, around 400 German settler families left the Duchy after 1813 and assumed farms in Bessarabia[8].

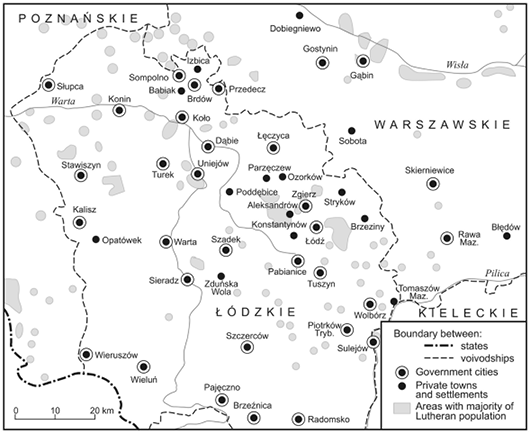

The turn of the 19th century was a period of the influx of German colonists, mainly to the rural areas of Central Poland, although there were migrations of craftsmen of German nationality (albeit initially marginal) to urban centres where the clothmaking industry was gradually developing. Up to 1815, craftsmen of German nationality ran clothmaking shops in over a dozen locations in central Poland (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Centres in Central Poland that noted an influx of clothmakers of German nationality up to 1815

Source: own work based on Kossmann, 1978, p. 244.

The most spectacular example of growth was the development of Ozorków, a village for which a development plan was prepared in 1807 at the village owner’s initiative to establish an industrial settlement. As a result, streets and plots of land were marked out for German clothmakers brought in from Dąbie. In June 1811, 64 clothmaker families settled in Ozorków, and their number increased to 117 by 1815 (including several families who had come from Saxony).[9]

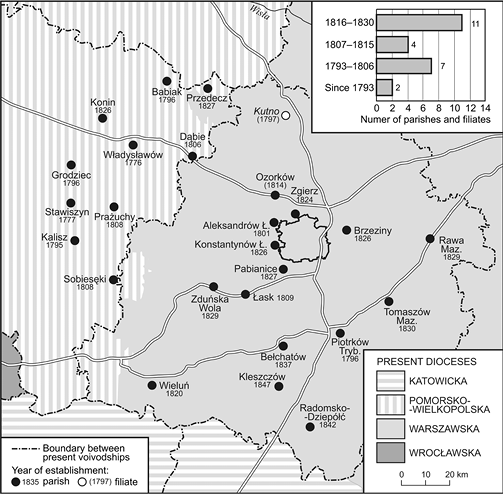

Over 90% of the German settlers who arrived in the second half of the 18th century and at the beginning of the 19th century were Lutheran. The first Augsburg Evangelical parishes in Central Poland were established in the 1770s (in Władysławowo and Stawiszyn). In the following years, Lutheran parishes appeared in places of larger concentrations of German settlers. By the establishment of the Duchy of Warsaw (until 1807), six parishes were established[10], with four more appearing between 1808 and 1815[11].

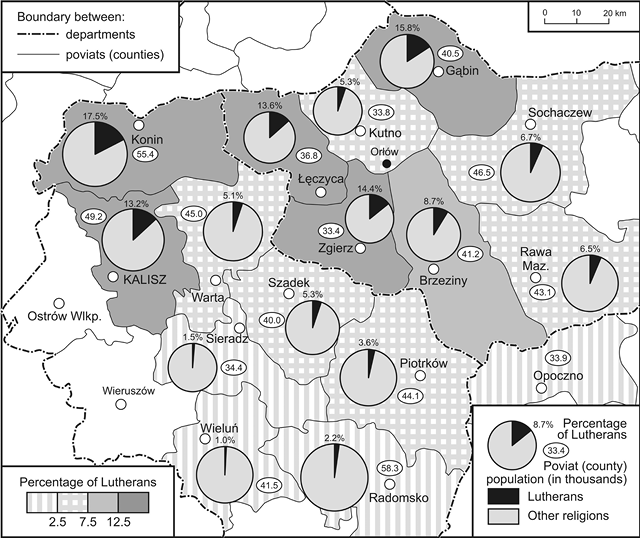

Fig. 3. Spatial distribution of the population of Augsburg Evangelical denomination in Central Poland in 1810 by county (poviat)

Source: own work based on Grossman, 1926, pp. 46–48, and Das ehemalige Königreich…, 1872.

In 1810, 363,300 representatives of the German minority of Augsburg Evangelical faith lived in the Duchy of Warsaw, constituting 8.3% of the total population[12]. In 1810 in Central Poland, in an area which included parts of the Kalisz and Warsaw departments and Opoczno county/poviat (Radom department), out of 667,100 inhabitants, 51,900 were of the Augsburg Evangelical faith, while only 1,300 belonged to the Reformed Evangelical church. In Kalisz with a total population of 7,300, which was the largest urban centre in the region at the time, the number of Lutherans reached 1,500 (Grossman, 1926, pp. 46−48). The Protestant population was concentrated mainly in the northern and north-western counties (poviats) of Central Poland: Konin (9,700 Protestants), Kalisz (6,500), Gostynin (6,400), Łęczyca (5,000), and Zgierz (4,800). At the same time, these were also counties in which Lutherans constituted the largest percentage of inhabitants, reaching 13–18% (see Fig. 3).

Established after the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the Kingdom of Poland occupied an area of 128,500 sq. km and had a population of nearly 3.3 million. The placement of the Kingdom’s western border, adopted at the congress in Vienna, meant that all the well-developed centres of textile production in Greater Poland were located outside its borders, on the Prussian side. At the time of its establishment, the Congress Kingdom was still an agricultural country with marginal textile production, which was already well-developed in neighbouring countries. Small craftworks producing fabrics and canvases that existed at the turn of the third decade of the 19th century in many urban centres in Central Poland was focused solely on meeting local needs (Różański, 1948, pp. 195−199).

The pro-immigration policy initiated during the Duchy of Warsaw period was continued by the authorities of the Kingdom of Poland in an effort to address low population density and a lack of a qualified workforce. The German population which migrated to Central Poland from abroad on the initiative of the government and private landowners settled both the colonised rural areas and the newly emerging factory settlements.

After 1815, agriculture was in a particularly difficult situation, having been heavily damaged by warfare. Populating the empty spots in government-owned properties was supposed to help boost the economy. The ineffectiveness of the serfdom system also brought about a growing interest of the nobility in the use of hired labour. To increase their income, they would place colonists in private estates, both in non-cultivated areas and areas claimed from ousted peasants.

The publication on 2 March 1816 of the Decision on the settlement of useful foreigners - manufacturers, craftsmen as well as farmers encouraged migration to the Polish territory. This law guaranteed immigrants, farmers, and craftsmen, who had settled in the Kingdom:

These incentives were supplemented by the decision adopted in the same year on the creation of a fund for the development of industry on the Polish territory; money from the fund could be used to establish factories, build houses for craftsmen, and regulate factory settlements, as well as for loans and grants for ‘useful foreigners.’ (Gąsiorowska, 1965, p. 71). Government cities were designated in Central Poland that were to become industrial centres in the future (see Fig. 4). The government’s actions encouraged similar efforts by private estate owners to settle foreign craftsmen and develop industry[13].

Fig. 4. Cities and settlements designated for industrial development in Central Poland in the 1820s

Source: own work.

From the point of view of colonists claiming the farms, the legal conditions under which they were given land for use were quite important. These conditions differed significantly from the rules of land use in serf villages. The settlers received plots of land on the basis of hereditary leases; after several years of exemption, they were obligated to pay a specified amount of rent to the land owner. The leased land could be inherited or sold.

The legal situation of industrial settlers in the Kingdom of Poland was secured by contracts, which guaranteed them numerous concessions and financial support. The government attached particular importance to the construction of water facilities, fulling mills, and bleaching plants, and supported these investments both organisationally and financially. So it was no wonder that already “by mid-1824, encouraged by the numerous privileges offered by the local government and the success of their compatriots, crowds of artisans from Bohemia and Saxony appeared in Poland.” (Flatt, 1853, p. 72)

As soon as the early 1820s, the government of the Kingdom of Poland launched large-scale activities to promote settlement. Recruitment campaigns were renewed several times. The government sent emissaries to all key Prussian, Saxon and Czech production centres, and their chief task was to bring industrial settlers. As a result, more and more craftsmen of German nationality settled in cities, where they assumed the role of industrialisation pioneers. Settlement in rural areas was also developing.

All these actions taken by the Polish government would have been much less effective had it not been for the difficult economic situation in German countries in the first decades of the 19th century. In Mecklenburg, Pomerania and other areas inhabited by the German population, the acreage of manor farmland was being increased at the expense of peasants who were being ousted from the land. Tax burdens grew and army conscription was a troublesome affair. Social inequality among the peasants was becoming more and more pronounced – the rich expanded their farms while the poor became free farm workers[14]. A large group of impoverished peasants evolved in Prussia, who were at times completely deprived of land. For them, the only option was to look for means of subsistence in exile. Even in the densely populated regions of Baden, Bavaria, Württemberg, and the Palatinate with high land fragmentation, social inequality among the peasantry was gradually increasing, thus prompting poorer groups to emigrate.

At the same time, in the field of non-agricultural activities, the increasing impoverishment of craftsmen was becoming key[15]. The difficult situation of German craftsmanship was caused by the competition that came from cheap, machine-made English products and the prohibitionist customs regulations that severed them from traditional Polish and Russian outlets. The situation was further aggravated by a long-lasting crop failure (1809–1816) and a famine in Württemberg and Hesse[16].

After the introduction of a customs tariff by Russia, the situation of small producers in Silesia, Brandenburg, and the Poznań region worsened.[17] The collapse of many handicraft factories in Saxony, northern Bohemia, and Silesia was accelerated by the progressive mechanisation of textile production.

While the migration from the German lands of people affected by the economic crisis was spontaneous, the influx of settlers to Polish territories who headed to private estates, as well as government and church properties, was the result of a well-thought-out economic policy, which was facilitated by a large supply and low price of land in the Kingdom of Poland. The migration of professionals to Central Poland was associated with the implementation of new knowledge regarding management, in the realm of both agricultural and non-agricultural activities. The activities of the Polish government, aimed at the development of the country’s economy and promotion of industrialisation, found support from the likes of highly entrepreneurial landowners seeking to introduce new, more effective management systems on their private land.

From the viewpoint of the development of the textile industry in the Kingdom and the associated settlement of German craftsmen, a return to protectionist policies and the introduction of a protective tariff on the import of textiles from Prussia was a key factor. The establishment of a customs union with Russia with its own protectionist policies was an equally important goal. By obtaining a guarantee of preferential customs tariffs, the Kingdom could secure access to absorptive markets in the East. The growing absorption of the internal market and government orders for the military also played a key role in the creation of demand for textile products.

The geographical origin of migrants arriving in Central Poland in the period prior to the Uprising was quite diverse. Above all, they came from Saxony, Württemberg (Swabia), Silesia, Bohemia, Mecklenburg, Prussia, and Hesse, as well as from the territory of the Grand Duchy of Poznań. At the same time, highly qualified professionals headed to industrial settlements, usually on a temporary basis, included people from other Western European countries, such as France (Lorraine and Alsace), Belgium, Switzerland (dyers), and England (mechanics).

At the turn of the 1820s, most of the industrial settlers came from the Prussian partition (Poznań, Lubuskie region), Pomerania, Brandenburg, and Silesia (Missalowa, 1964, p. 60). The migration of craftsmen from the crisis-stricken linen industry in Silesia intensified between 1826 and 1830. From 1827, a growing influx of newcomers from West Prussia was observed (Missalowa, 1964, p. 66). From 1824 to 1830, numerous craftsmen, mainly of German nationality, came from the Sudeten textile production regions of Bohemia and Moravia.

Many industrial settlers came from Saxony where the government pursued a liberal migration policy and where the textile industry, strongly developed in the 17th and 18th centuries, was experiencing difficulties after the loss of eastern outlets and in the face of increasing competition from English products. The impoverished Saxon weavers massively migrated to the Kingdom of Poland from the mid-1820s until the outbreak of the November Uprising in 1831 (and later between the Uprisings, from 1837 to 1844) (Missalowa, 1964, pp. 76, 83). Most of them headed for Łódź and the nearby centres of textile production.

The first settlers to appear in Łódź were Saxons and Germans from Bohemian territories (northern Bohemia)[18]. Migrants coming in the following years to Łódź, which was a rapidly growing industrial centre, mainly came from: Prussia (Brandenburg) and Lower Silesia[19], Saxony – especially its eastern part[20], Bohemia[21], and the Duchy of Poznań[22] (see Rynkowska, 1958, p. 53).

As the settlers often came in tight-knit groups, many localities in Central Poland were inhabited by newcomers from the same region.[23]

The social and professional structure of the settlers coming to Central Poland in the decades that followed clearly differed from that of the migrants arriving at the turn of the 19th century. In the first three decades of the 19th century, along with the increasing scale of migration, representatives of agricultural professions constituted an ever smaller share of the total number of settlers, while the influx of craftsmen was rapidly increasing.

Despite the fact that textile production was dynamically developing, in the initial phase of industrialisation in the 1820s, the transition of agricultural colonists to jobs in textile processing was previously unheard of. Rural settlements settled by German immigrants were usually sparsely populated, with a predominance of poor people primarily interested in the cultivation of land obtained under favourable conditions. Thus, agricultural colonists could not constitute significant support for developing production centres (see Woźniak, 1993, pp. 113–130).

Most of the Germans who migrated between 1815 and 1830 were industrial settlers – specialists in the field of textile production included weavers, and spinners, as well as particularly sought-after fullers, combers, and dyers. Representatives of other professions also came, including bricklayers, carpenters, workshop manufacturers, saddlers, etc. Clothmakers dominated in the first wave of migration. The following wave of migrants included specialists in the production of cotton products, while linen canvas manufacturers appeared at the very end.

The first wave of industrial settlers were craftsmen and small industrialists from the eastern provinces of Germany who needed government support, yet most of them had the required qualifications to engage in production activities. The most numerous group among the industrial settlers were small producers who only on occasion employed a few journeymen or makers. Along with the qualified workforce, foremen and journeymen, large groups of unskilled makers appeared, who came mainly from Prussia. Many of the newcomers were people who were not proficient enough in their profession, so to make sure that government expenditures for the settlers would not be wasted, a regulation was introduced already in March 1819 which stated that migrants could obtain a permission to settle only if they previously confirmed their wealth or their knowledge of the profession (Woźniak, 1993, p. 129).

The level of wealth of the earliest migrants was not significant enough to ensure the implementation of the ambitious assumptions of the government policy aimed at the development of large-scale textile production which would enable effective competition with the rapidly developing textile industry in Western Europe. The government of the Kingdom of Poland was not able to meet the growing credit needs of the massively migrating clothmakers, while the commissioning of larger and more specialised factories required the involvement of foreign capital. Therefore, efforts were made to recruit industrialists with more available capital from Saxony, Bohemia, and Prussia[24]. Attracting wealthier factory owners meant that the earlier economic equality among the settlers was swayed and small producers, often operating in the outwork system, became a link in the production chain dependent on wealthier entrepreneurs.

The strongest binding force of the agricultural colonists and craftsmen originating from the territory of the German Reich and bordering regions and settling in Polish territory was language and religion (Protestant faith) (see Woźniak, 1993, p. 11). For many years in Central Poland, they constituted a clearly distinguishable national group, in which acculturation processes occurred relatively slowly and only a small percentage of migrants in the first generation became Polonised. At least by the mid-19th century, the German diaspora maintained a particularly strong awareness of belonging to their ‘small homelands’ (‘Heimat’), and settlers who migrated to Polish lands would define themselves as subjects of Prussia, Württemberg, or Saxony[25]. At the end of the 18th century and in the first half of the 19th century, people from Aachen, Saxony, Bavaria, or Prussia were completely different Germans, with a different sense of national affinity (cf. Śmiałowski, 1999, p. 209). Most of the settlers from Württemberg, Hesse, Baden, and the Palatinate were ethnic Swabians[26](Woźniak, 1993, p. 11), whose differences, which also included language resulting from the use of a specific Swabian dialect, were often an obstacle in communicating with the area, though they were also German (see Woźniak, 1993, p. 88).

Despite a clear sense of identity of their origins related to the attachment to their ‘small homelands’ and migration from various, not necessarily German regions, i.e., Saxony, Prussia, Silesia, Baden, Württemberg, Pomerania, the Bohemia, or Greater Poland, the vast majority of migrants settling in Central Poland were bound with German culture (Woźniak, 1998, p. 88). Upon arrival in Poland, they were cast into a foreign environment and by living in the diaspora, they showed a quite understandable tendency to strengthen mutual contacts, show solidarity in their attitudes, and cultivate tradition, language, and faith (see Śmiałowski, 1999, p. 210). This tendency to separate was reflected both in the spatial dimension, which was demonstrated by the way they concentrated within newly formed colonies and settlements, as well as in the professional sphere.

The German colonies in Central Poland in the early 19th century were quite hermetic, and the scope of contact between the settlers and the native Polish population was relatively small. Germans rarely settled in villages previously inhabited by the Polish population, and likewise, immigrants rarely claimed farms abandoned by Polish peasants[27].

In addition, contacts with cities by German colonists who settled in the countryside during the first decades of the 19th century were quite sporadic, which resulted from communication difficulties and quite frequently a significant distance from the nearest urban centre. A significant degree of self-sufficiency in the field of crafts that secured daily existence, was characteristic of the rural settlers; so this also limited the need for contact with the external world and strengthened the isolation of the rural German minority communities.

Among German immigrants representing non-agricultural professions, there was a clear tendency for separation in the sphere of professional and social activity, which was manifested by their reluctance to join already existing Polish-Catholic associations or craft guilds. Once groups of settlers built sufficiently strong clusters, they established their own German organisations[28]. In larger production centres, this led to the formation of a type of professional ghettos, isolated from the Polish society to a certain extent and characterised by its cultural, linguistic, and religious distinctiveness. The size of the clusters of German weavers, the guild traditions of crafts, apprenticeships, and the transition of workshops to children, as well as numerous economic ties with representatives of their own national group meant that many handicraft colonies in Central Poland (and especially in the Łódź district) retained their distinct character for a long time. The processes of acculturation and assimilation unfolded much faster in those regions where the number of settlers was smaller, contacts with the social environment were more extensive, and the professional structure of German migrants was more diverse (Wiech, 1999, pp. 107–108). The more dispersed clusters of German craftsmen, where second generation migrants often integrated with the Polish population, were losing the features typical of German factory settlements at a faster rate.

The gradually developing education system for the children of German settlers helped to maintain their sense of national identity. Already in the times of the Duchy of Warsaw, a network of Evangelical religious schools was developed with German as the language of instruction, with no Polish language instruction in the curriculum[29]. Nearly all the children of German-speaking settlers attended Evangelical schools at the beginning of the 19th century.

Assimilation processes were counteracted by the religious distinctiveness of the majority of the settlers who belonged to the Augsburg Evangelical Church, which became “A nearly exclusively German church.” (Bursche, 1925, p. 23.) Religious affiliation, which usually has a hereditary character, became an element of tradition that had an effect on cultural rooting and constituted a permanent component of social, and often national, consciousness. This factor was particularly important in rural areas inhabited by the more dispersed communities of German migrants. The religious community supported the integration of fellow believers living a certain distance away – the parish was the centre of religious life, as well as community, social, and cultural life, for settlers living in nearby villages (see Stegner, 1994, pp. 6–7). Marriages within one’s own religious and national group contributed to maintaining national identity.

In the pioneer period that lasted until the end of the 1820s, assimilation processes were quite limited in scope, especially in places where the German minority formed larger clusters, and concerned a small number of people. Rather, those were times of the initial adaptation of the German environment to new, rapidly changing living conditions in a new place of settlement (Pytlas, 1996, p. 14).

According to various sources, the size and spatial distribution of German settlements in the Kingdom of Poland before the outbreak of the November Uprising were very diverse and difficult to verify. Estimates of the number of settlers range from 35,000 up to 300,000, where about 1/4 of the total number of migrants were agricultural colonists (see e.g., Bajer, 1958, p. 46). The source of these differences seems to lie not only in the ideological attitude of the authors, but also in different calculation methodologies[30]. A total of 300,000 settlers is an undoubtedly overestimated figure (including 250,000 between 1818 and 1828) as provided by the German researcher Gustaw Schmoller (Schmoller, 1873). At the same time, the figures provided by the Polish side, which spoke of 55,000 German immigrants (around 10,000 families) who arrived between 1810 and 1827, was vastly underestimated[31]. According to a report of the Minister of Religious Denominations and Public Education from 1823, there were 128,000 Evangelist immigrants in the Kingdom of Poland (without settlers of German nationality of other religions)[32]. Most likely, before the outbreak of the November Uprising, the territory of the Kingdom of Poland was inhabited by about 260,000 settlers of German origin who came during the previous 50 years (see Badziak et al., 2014, p. 37).

In the period before the Uprising, German settlers came to the territories of Central Poland mainly in groups – brought by the government or private owners as part of a planned colonisation action – and created tight-knit agricultural or handicraft settlements. Individuals or families, whose places of settlement were more spatially dispersed, migrated less frequently. In 1818, the first weavers from Greater Poland, which was severed in 1815 from existing markets, settled in Brzeziny and Zduńska Wola, and in 1819 in Zgierz (Kaczmarczyk, 1945, p. 195). By 1830, German-speaking migrants found their way to practically every city or land estate. The migration of craftsmen to jobs in the clothmaking industry in the 1820s was facilitated by the fact that it was a continuation of the earlier influx of agricultural colonists from Germany, so newcomers arrived in a region where their compatriots had been settling for over three decades.

Immigrants seeking employment in textile production settled mainly in state-owned estates and were particularly willing to opt for government cities slated to be industrial centres, where unlike many settlements established on private lands, they could live for free. Industrial settlements established by private landowners that had not yet obtained municipal rights, were less popular; settlers feared the arbitrariness of private landowners, who sometimes imposed unfavourable provisions in their contracts.

The activities of the authorities of the Kingdom of Poland for economic activation were mainly focused on two provinces (voivodeships): Kalisz and Warsaw. The direction of the migration of professional craftsmen from Germany was greatly influenced by the decision of the Mazovia Province Commission of 1820 to allocate selected centres which had sufficient water resources needed for the operation of fulleries and dyeworks for the development of clothmaking. In the initial intentions of the government, the planned clothmaking district was to include Łęczyca as the main centre along with the surrounding cities (Zgierz, Łódź, Dąbie, Przedecz, and Gostynin). The authorities prepared plans for these cities. Plots were allocated for settlers, fulleries were established, and brickyards were built.

In the first period, Zgierz attracted the largest number of industrial settlers, where 230 plots of land were designated for a new handicraft settlement as early as 1821, while the number of inhabitants increased by almost 16 times to 8,900 people between 1815 and 1828[33]. Aleksandrów also saw a rapid development in the first half of the 1820s[34].

Foreign clothmakers in large numbers were accepted by many cities (government and private), including: Kalisz, Zduńska Wola, Sieradz, Zelów, Turek, Koło, Pabianice, Bełchatów, Zgierz, Konstantynów, Ozorków, Dąbie, Ksawerów, Tomaszów Mazowiecki, Brzeziny, and Łęczyca. At the same time, until the early 1820s, immigrants generally avoided Łódź, which had a typical agricultural character despite having municipal rights. The city was surrounded by a ring of German peasant settlements established at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century.

The scale of the influx of immigrants to centres which were developing textile production was evidenced by the population increase during the fifteen year period before the Uprising in what was then the Mazovia province in the north-eastern part of Central Poland (see Fig. 5).

In the first period, the workforce factor had a decisive influence on the location of the newly created production centres, and craftsmen migrating from German lands mainly headed for locations closer to the western border of the Kingdom of Poland (in the Kalisz province). The years that followed brought faster colonisation by settlements further east (in the Warsaw province), with a vast majority of them located in the strip stretching along the western border of the Warsaw province (from Izbica to Tomaszów Mazowiecki) (see Ostrowski, 1949, pp. 34–35). The key determinants here were the outlets and the location of this region closer to the border with Russia, to where most of the textile production was delivered.

Fig. 5. Population growth in cities of Central Poland (Mazowsze province) between 1815 and 1828

Source: own work based on Lück, 1934, p. 336.

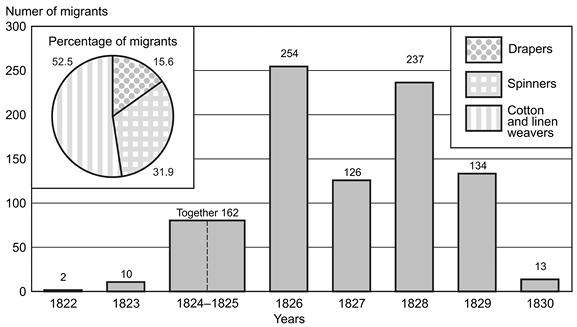

The influx of industrial settlers to Łódź, which had been avoided earlier, was initiated by the designation of 202 plots in the newly created clothmaking settlement called Nowe Miasto in 1822. The first group of immigrants arrived in Lodz in the autumn of 1823; among them there were about a dozen clothmakers and a comber from Saxony, as well as several construction experts to build textile workshops and houses. Nearly 200 skilled craftsmen settled in the city between1823 and 1825, most of whom (about 60%) were weavers. The establishment in 1824 of a settlement for cotton and linen weavers with 307 plots, and a settlement for linen spinners with 167 plots in 1825, led to rapidly increasing migration of skilled German settlers in the following years. The first cotton weavers arrived in September 1924. By the mid-1820s, Łódź became an attractive place to live.

The spatial development of the Łódź textile production centre was further complemented with the establishment of yet another settlement (weaving/spinning) called Ślązaki with 42 plots in 1828. All these actions initiated by the government resulted in the designation of 366 plots of land to immigrants arriving in Łódź by 1829 (see Lorentz, 1930, p. 183).

Fig. 6. Number and occupational structure of migrants settled in Łódź from 1822 to 1830

Source: own work based on Rynkowska, 1951.

In the 1820s, Łódź, which had a population of 799 inhabitants in 1821, saw the arrival of about 1,000 immigrant craftsmen, meaning that around 4,000 people of their nationality settled in the city[35]. The period from 1826 to 1829 saw a particular increase in the influx of migrants, dominated by cotton-linen weavers (cf. 6). As a result of the population processes occurring in the 1820s, the national structure of Łódź changed completely; at the turn of the 1830s, it became a multinational city with a large proportion of Germans and one of the main centres of the German population in Central Poland[36]. In 1839, as many as 68% of the permanent inhabitants of Łódź were allochthoons (people born outside the city) (Kossmann, 1936, p. 36).

Over time, many German industrial settlers changed their original place of settlement, looking for increased support and more favourable income-earning opportunities. Contributing to these immigrant movements was the competitive battle for textile professionals not only between the subregions of Central Poland (Kalisz and Mazovia provinces), but also through actions taken by the owners of private land estates and cities who tried to settle newcomers in their territories. In time, settlers coming from German lands gradually started to inhabit areas increasingly further east, but only a few decided to settle beyond the line of the Vistula.

Apart from the industrial settlements established in the 1820s, Central Poland was the location of numerous colonies established in government and private estates by migrating peasants. In many estates, there were at least a few such colonies and each of them was inhabited by anywhere from a few to a dozen German families. Significant concentrations of Germans inhabited the numerous agricultural colonies surrounding Łódź. A certain (but rather small) share of these colonies fuelled the fast-developing textile production centres by providing craftsmen for clothmaking. Incomplete data on the distribution of German agricultural colonists in Central Poland indicate that before the outbreak of the January Uprising, they were concentrated mainly in four districts: Łęczyca, Kalisz, Piotrków, and Rawa, where a total of about 28,000 agricultural settlers lived.

The influx of German people (approximately 90% of which were of the Augsburg Evangelical faith) to the lands of Central Poland over several decades at the turn of the 19th century was reflected (also from a spatial perspective) in the time of establishment and distribution of Lutheran parishes. Their number almost doubled during the first fifteen years of the existence of the Kingdom of Poland (1816–1830). A total of 11 new parishes were established, of which half were in the rapidly developing industrial district of Łódź (see Fig. 7)

German settlement in the Kingdom of Poland in the period before the Uprising (up to 1830), both agricultural and industrial and regardless of its character, demonstrated a clear tendency towards spatial concentration. The largest concentration of the German minority was in the district of Łódź, located closest to the Prussian border. Unlike in the Middle Ages (when migrant journeymen established workshops far away from their homelands), cases of migration of individual foreigners (without government support) to establish individual craftsmanship activity in cities and villages located in provincial areas were rare (see Wiech, 1999, p. 99).

Fig. 7. Distribution of parishes and branches of the Augsburg Evangelical Church in Central Poland in 1830 (according to the date of establishment)

Source: own work based on Kneifel, 1971, pp. 292–295.

In 1827, the population of the German minority settled within the Kingdom of Poland totalled nearly 300,000. Just under 40% lived in two provinces of Central Poland, i.e., Mazovia, which included the Łódź district (70,500 people of German nationality), and Kalisz (45,100)[37].

In the decade prior to the Uprising, industrial settlers were definitely the dominating group among the newcomers. The influx of a professional workforce, almost entirely recruited from people of German origin, conditioned the development of clothmaking, and the main centres of textile production were also locations of a high concentration of German settlement. The spatial distribution of this ethnic group at the end of the 1820s was associated with the distribution of cloth production. In the scale of the entire Congress Kingdom, approx. 4/5 of this production was located in Central Poland, in the eastern part of the Mazovia province (close to 3/5 of the total number of wool spindles in the Kingdom of Poland were located here) and in the Kalisz voivodship (about 1/4 of the total number of woolen spindles in the Kingdom of Poland), and above all in the Mazovia-Kalisz textile district (mainly the Łęczyca district), the most important centre of which at that time was Zgierz with its surrounding clothmaking settlements. In addition to Zgierz in the Łęczyca region, Ozorków, Aleksandrów, and Konstantynów held a key position in terms of textile production, followed by a slightly lower ranking Łódź. Apart from the Łęczyca region, the most significant clothmaking centres included Tomaszów Mazowiecki, Kalisz, Sieradz, and Opatówek. The period of the first heavy influx of German craftsmen to the Polish industry, which was most intense in the mid-1830s, ended with the outbreak of the November Uprising in 1831.

The rich body of literature devoted to the German minority in Poland offers an array of publications by both Polish and German researchers who provide a reliable description and possibly objective assessment of this ethnic group. However, this subject matter was often an issue of considerable controversy and differing interpretations of historical facts, while the formulated conclusions depended on who raised the topic and when, as well as the ideological position from which the matter was addressed. The realities of the functioning of the German minority in Poland were much more complex than the simple and generalised message we sometimes find in literature. The situation was quite different in various parts of the country, in different social groups, and in different periods.

The German population that came to Central Poland in the 19th century made an unquestionable, though difficult to measure, contribution to the development of the region and its main centre, Łódź, a city which over the course of several decades grew from a small neglected settlement to a key industrial centre. The settlers coming from abroad possessed traits very typical of Protestants – they were diligent and thrifty, and had a strong sense of responsibility and respect for work. Their willingness to invest at the expense of limiting current consumption facilitated their adaptation to a new place of residence and was of particular importance in the period of accelerated industrialisation (see: Kończyński, 1911, p. 60).

In the common perception, the German colonists constituted a homogeneous group, the main distinguishing feature of which was their language and faith. Yet in fact, the settlers from German lands were a very diverse social group. There were a number of reasons for this differentiation. The differences between the settlers came above all from their territorial origin – they migrated from Pomerania, the Poznań region, Saxony, Swabia, Silesia, and areas located on the lower Vistula (Niederunger). This in turn was associated with significant differences in the sphere of culture, differing customs, building techniques, and farming methods. The linguistic differences were significant, especially in the case of migrants from the region of Württemberg and Baden (the Swabian dialect vastly differed from the German spoken by migrants from other regions). And most importantly, at the beginning of the 19th century, German settlers felt a stronger bond with the region they came from than with the German nation. The differences inherited from ancestors persisted for many years, while the processes of homogenisation within such a diverse German minority were often much weaker and slower than the process of Polonisation of future settler generations.

Differences in the realm of religion were no less important. Individual Lutheran congregations were diverse not only in terms of organisation but also in the liturgical sphere and all too often “An evangelical who attended a service in another, sometimes even neighbouring parish, felt like he was in a church of a different denomination.”(Gastpary, 1977, p. 312). Some of the German settlers belonged to the Roman Catholic Church, while the group of Protestants included several smaller groups of Christians, in addition to the dominant Lutherans.

In the first and second generation of immigrants from German lands who came to Central Poland at the end of the 18th and at the beginning of the 19th century, the social integration process was still quite slow. The colonists and settlers living in the diaspora developed a certain pattern of existence, which focused on their immediate environment separating them from the outside world, while retaining their mother tongue and religious tradition was more an expression of traditionalist consciousness than national identity.

This did not change until the later decades of the 19th century, followed by World War I and the political events of the inter-war period; accompanied by gradual integration and assimilation processes, these events influenced social change which in turn redefined the ethnic identity of the German minority and its place in the community of their country of settlement.

BADZIAK, K., CHYLAK, K. and ŁAPA, M. (2014), Łódź wielowyznaniowa. Dzieje wspólnot religijnych do 1914 r., Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego. https://doi.org/10.18778/7969-512-6

BAJER, K. (1958), Przemysł włókienniczy na ziemiach polskich od początku XIX wieku do 1939 roku. Zarys historyczno-ekonomiczny, Łódź.

BREYER, A. (1941), Deutsche Tuchmachereinwanderung in den Ostmitteleuropäischen Raum von 1550 bis 1830, Posen-Leipzig.

BUDZIAREK, M. (2001), ʽKatolicy niemieccy w Łodzi (wybrane zagadnienia)ʼ, [in:] KUCZYŃSKI, K. A. and RATECKA, B. (eds), Niemcy w dziejach Łodzi do 1945 r., Łódź, pp. 41–76.

BURSCHE, E. (1925), ʽWstęp informacyjny o istniejących w Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej Kościołach Ewangelickichʼ, Rocznik Ewangelicki, pp. 17–43.

Das ehemalige Königreich Polen, nach den Grenzen von 1772: mit Angabe der Theilungslinien von 1772, 1793 & 1795, L. Friederichsen & Co. Geographische – Verlagshandlung; (Lith. Anst. v. Leopold Kraatz), Hamburg-Berlin, 1872.

FLATT, O. (1853), Opis miasta Łodzi pod względem historycznym, statystycznym i przemysłowym, Warsaw.

FRIEDMAN, F. (1933), ʽPoczątki przemysłu w Łodzi 1823–1830ʼ, Rocznik Łódzki, 3, Łódź, pp. 97–186.

GASTPARY, W. (1977), Historia protestantyzmu w Polsce od połowy XVIII w. do I wojny światowej, Warszawa: Chrześcijańska Akademia Teologiczna, p. 312.

GĄSIOROWSKA, N. (1965), ʽOsadnictwo fabryczneʼ, Ekonomista Year XXII, 1922, I-II [in:] GĄSIOROWSKA-GRABOWSKA, N., Z dziejów przemysłu w Królestwie Polskim, Warsaw, pp. 70–135.

GINSBERT, A. (1962), Łódź – studium monograficzne, Łódź: Wydawnictwo Łódzkie.

GOLDBERG, J. (1968), ʽOśrodki przemysłowe we wschodniej Wielkopolsce w XVIII w.ʼ, Roczniki Dziejów Społecznych i Gospodarczych, XXIX, Poznań, pp. 55–85.

GROSSMAN, H. (1926), ʽStruktura społeczna i gospodarcza Księstwa Warszawskiego na podstawie spisów ludności 1808–1810ʼ, Kwartalnik Statystyczny 1925, II, GUS, Warsaw, pp. 1–108.

HEIKE, O. (1979), 150 Jahre Schwabensiedlungen in Polen 1795–1945, Leverkusen.

INGLOT, S. (1945), Kolonizacja wewnętrzna a napływ Niemców do Polski od XVI–XVIII wieku, Krakow.

JANCZAK, J. (1982), ʽLudność Łodzi przemysłowej 1820–1914ʼ, Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Historica, 11, Łódź.

KACZMARCZYK, Z. (1945), Kolonizacja niemiecka na wschód od Odry, Poznań.

KNEIFEL, E. (1971), Die evangelisch-augsburgischen Gemeinden in Polen 1555–1939. Eine Parochialgeschichte in Einzeldarstellungen, Vierkierchen Vierkirchen über München.

KOŃCZYŃSKI, J. (1911), Stan moralny społeczeństwa polskiego, Warsaw.

KOSSMANN, E. O. (1936), ʽDas alte deutsche Lodz auf Grund der städtischen Seelenbücherʼ, Deutsche Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift für Polen, Hf. XXX, pp. 21–47.

KOSSMANN, E. O. (1937), ʽStammesspiegel deutscher Dörfer in Mittelpolenʼ, Jomsburg, 3, pp. 329–342.

KOSSMANN, O. (1978), Die Deutschen in Polen seit der Reformation. Historisch-geographische skizzen. Siedlung – Sozialstruktur – Wirtschaft, Marburg am Lahn.

LORENTZ, Z. (ed.) (1928), ʽTrzy raporty Rajmunda Rembielińskiego prezesa Komisji Województwa Mazowieckiego z objazdu obwodu łęczyckiego w 1820 r.ʼ, Rocznik Oddziału Łódzkiego Polskiego Towarzystwa Historycznego, 1.

LORENTZ, Z. (ed.) (1930), ʽRaport prezesa Komisji Wojewódzkiej Mazowieckiej o stanie przemysłu włókienniczego w roku 1828ʼ, Rocznik Oddziału Łódzkiego Polskiego Towarzystwa Historycznego 1929–1930, Łódź, pp. 173–192.

LÜCK, K. (1934), Deutsche Aufbaukräfte in der Entwicklung Polens, Plauen.

MARSZAŁ, T. (2020), Mniejszość niemiecka w Polsce Środkowej. Geneza, rozmieszczenie i struktura od końca XVIII w. do II wojny światowej, Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego.

MENCEL, T. (1959), ʽPod zaborem pruskim i w Księstwie Warszawskim (1793–1814)ʼ [in:] RUSIŃSKI, W. (ed.), Dzieje wsi wielkopolskiej, Poznań, pp. 115–140.

MISSALOWA, G. (1964), ʽPrzemysłʼ Studia nad powstaniem łódzkiego okręgu przemysłowego (1815–1870), 1, Łódź: Wydawnictwo Łódzkie.

NICHTWEISS, J. (1954), Das Baurnlegen in Mecklenburg. Eine Untersuchung zur Geschichte der Bauernschaft und der zweiten Leibeigenschaft in Mecklenburg bis zum Brginn des 19 Jahrhunderts, Berlin.

OSTROWSKI, W. (1949), Świetna karta z dziejów planowania w Polsce 1815–1830, Warsaw.

PYTLAK, A. (1917), Die deutschen Kolonisationsbestrebungen auf den Staatsdomänen im Königreich Polen (1793–1864), Leipzig.

PYTLAS, S. (1996), ʽProblemy asymilacji i polonizacji społeczności niemieckiej w Łodzi do 1914 r.ʼ, [in:] WILK, M. (ed.), Niemcy w Łodzi do 1939 r., Łódź, pp. 13–20.

RODECKI, F. (1830), Obraz jeograficzno-statystyczny Królestwa Polskiego, Warsaw.

RÓŻAŃSKI, A. (1948), ʽPróba określenia liczby imigrantów niemieckich przybyłych na teren Królestwaʼ, Roczniki Dziejów Społecznych i Gospodarczych, Poznań, 10, pp. 185–201.

RUTKOWSKI, J. (1953), Historia gospodarcza Polski (do 1864), Warsaw.

RYNKOWSKA, A. (1951), ʽDziałalność gospodarcza władz Królestwa Polskiego na terenie Łodzi przemysłowej w latach 1821–1831ʼ, Łódź: ŁTN, Wydz. 2, 5.

SCHMOLLER, G. (1870), Zur Geschichte der deutschen Kleingewerbe im 19. Jahrhundert, Halle.

SCHMOLLER, G. (1873), Die Entwicklung und die Krisis der deutschen Weberei im 19. Jahrhundert, Berlin.

SIMSCH, A. (1983), Die Wirtschaftpolitik des preussischen Staates in der Provinz Südpreussen 1793–1806/7, Berlin.

SMOLEŃSKI, W. (1901), ʽRządy pruskie na ziemiach polskich 1793–1807ʼ, Pisma Historyczne, III, Krakow.

SOBCZYŃSKI, M. (2000), ʽHistoria powołania i przemiany administracyjne województwa łódzkiegoʼ, [in:] SOBCZYŃSKI, M. and MICHALSKI, W. (eds.), Województwo łódzkie na tle przemian administracyjnych Polski, Łódź, pp. 7–21.

STEGNER, T. (1994), ʽWięź wyznaniowa a narodowaʼ, [in:] STEGNER, T. (ed.), Naród i religia, Gdańsk, pp. 6–16.

ŚLADKOWSKI, S. (1969), Kolonizacja niemiecka w południowo-wschodniej części Królestwa Polskiego w latach 1815–1915, Lublin.

ŚMIAŁOWSKI, J. (1999), ʽNiemców polskich dylematy wyborówʼ, [in:] CABAN, W. (ed.), Niemieccy osadnicy w Królestwie Polskim 1815–1915, Kielce, pp. 209–224.

WĄSICKI, J. (1953), ʽKolonizacja niemiecka w okresie Prus Południowych 1793–1806’, Przegląd Zachodni Year 8 (9/10), pp. 137–179.

WĄSICKI, J. (1957), Ziemie polskie pod zaborem pruskim. Prusy Południowe 1793–1806, Wrocław.

WERESZYCKI, H. (1986), Pod berłem Habsburgów, Krakow.

WIECH, S. (1999), ʽRzemieślnicy i przedsiębiorcy niemieckiego pochodzenia na prowincji Królestwa Polskiego 1815–1914’, [in:] CABAN, W. (ed.), Niemieccy osadnicy w Królestwie Polskim 1815–1915, Kielce, pp. 95–116.

WINIARZ, A. (1998), ʽUdział mniejszości niemieckiej w życiu kulturalno-oświatowym księstwa Warszawskiego i Królestwa Polskiego (1807–1915)’, [in:] BILEWICZ, A. and WALASEK, S. (eds), Rola mniejszości narodowych w kulturze i oświacie polskiej w latach 1700–1939, Wrocław, pp. 123–138.

WOBŁYJ, K. G. (1909), Oczierki po istorji polskoj cabricznoj promyszlennosti, I, ʽ1764–1830’, Kyiv.

WOŹNIAK, K. (1993), ʽWokół sporów o znaczenie rolnego osadnictwa niemieckiego w łódzkim okręgu przemysłowym’, Acta Universiitatis Lodziensis. Folia Historica, 49, pp. 113–130.

WOŹNIAK, K. (1997), ʽSpory o genezę Łodzi przemysłowej w pracach historycznych autorów, polskich, niemieckich i żydowskich’, [in:] SAMUŚ, P. (ed.) Polacy, Niemcy, Żydzi w Łodzi w XIX–XX w.; sąsiedzi dalecy i bliscy, Łódź, pp. 9–26.

WOŹNIAK, K. (1998), ʽMiastotwórcza rola łódzkich ewangelików w latach 1820–1939’ [in:] MILERSKI, B. and WOŹNIAK, K. (eds), Przeszłość przyszłości. Z dziejów luteranizmu w Łodzi i regionie, Łódź, pp. 83–116.

WOŹNIAK, K. P. (2013), Niemieckie osadnictwo wiejskie między Prosną a Pilicą i Wisłą od lat 70. XVIII w. do 1866 roku. Proces i jego interpretacje, Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego. https://doi.org/10.18778/7525-960-5

WOŹNIAK, K. P. (2015), ʽPruskie wsie liniowe w okolicach Łodzi i ich mieszkańcy w początkach XIX w.’, Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Geographica Socio-Oeconomica, 21, pp. 101–117. https://doi.org/10.18778/1508-1117.21.06

WRÓBEL, E. and WRÓBEL, J. (1988), ʽAleksandrów Łódzki 1816–1831’, Mówią Wieki, 10, pp. 15–19.

ZDZITOWIECKI, J. (1948), Książę-Minister Franciszek Xavery Drucki-Lubecki 1778–1846, Warsaw.

Received: 6.02.2022. Revised: 20.02.2022. Accepted: 9.03.2022.