Abstract. Integrating the ecosystem services (ES) concept into land-use planning has been the focus of researchers in recent years. Forwarding this objective in order to foster human well-being, urban and regional planning became the focus of research efforts. Furthermore, governance research has been beneficial in studying the coupling of ecosystem services and planning processes. Thus, in this explorative case study we have analysed the governance of urban and regional planning in two case studies – Rostock and Munich – in order to gain insights about the role and value of ecosystem services among planning actors. We conducted semi-structured interviews to identify relevant parameters to facilitate integrational approaches of ecosystem services into decision-making in the context of cross-sectoral urban and regional planning. Based on our results, we argue for a change of the perspective of ES within planning practice. Instead of ecological or economic endeavours, the contribution of ES to human well-being should be in the centre of attention. Human well-being as an overarching aspiration may have the potential to shift ecosystem services from sectoral to cross-sectoral planning.

Key words: urban ecosystem services, land use planning, urban and regional planning, ecosystem service integration, science-policy interface

Cities not only have an impact on their environment but are also dependent on it. The relationship between the city and nature within urban space is increasingly being considered and discussed from the perspective of urban nature and green infrastructure for sustainable urban development. This often raises the question of the benefits of urban nature for planners in the context of changes to land use – which is why an examination of the concept of ecosystem services seems inevitable (Breuste, 2019, p. 100). Ecosystem services (ES) not only provide essential services, e.g., drinking water or food supply, but also contribute significantly to the quality of life in cities and to human well-being (Kowarik et al., 2017; MEA, 2005). Particularly in view of global climate change, the integration of ES into urban and regional planning is increasingly becoming the focus of practice-oriented research (Geneletti et al., 2020b).

In recent years, the number of publications on the integration of ES explicitly aimed at supporting land-use planning decisions by trying to address real-world planning issues has increased (Longato et al., 2021). In addition to research on the recording and assessment of ES (Gómez-Baggethun and Barton, 2013; Burkhard et al., 2014; Förster et al., 2015; Kowarik et al., 2017; Potschin-Young et al., 2018), concrete studies on the integration of ES in land-use planning have also been published (Mascarenhas et al., 2014; Kaczorowska et al., 2016; Terzi et al., 2020), also considering legally binding land-use planning, for instance in Germany (Deppisch et al., 2021). Thus, the opportunities and barriers of ES integration in urban and regional planning have been studied and discussed (Luederitz et al., 2015; Forkink, 2017; Longato et al., 2021).

Although there are recommendations for action on ES integration in strategic environmental assessments (SEAs) (e.g., UNEP, 2014), comprehensive implementation in land-use planning practice outside of research projects is still scarce, although planners are equipped with appropriate tools, such as permits, use options, and restrictions, to implement ES in making informed decisions (Geneletti et al., 2020a). However, Mascarenhas et al. (2014) have pointed out in their case study in Portugal that planners consider ES as already integrated in SEAs and in regional land-use plans. They have concluded that integration either exists implicitly in the planning documents or that there is a gap between planners’ perception and the actual degree of integration (ibid.) But studies for Germany have shown that if just cross-cutting land-use planning is considered and not landscape-planning and further specific plans, many gaps of references to and preserving of and development of ES are lacking in current plans (Deppisch et al., 2022). Furthermore, a review of several case studies by Longato et al. (2021) shows that although there have been many efforts by ES researchers to develop universal classifications and tools to ensure broad applicability and comparability, a deep understanding of the local context is a prerequisite for providing effective planning support for ES integration. As Arkema (2006, p. 531) phrased it: “Site differences in management goals, ecosystem function, and human use may affect the extent to which an ecosystem-based approach is incorporated into management planning.”

In researching the integration of ES, a focus has also been placed on the (urban) governance of ES (Newig, 2011; Primmer and Furman, 2012; Wilkinson et al., 2013; Connolly et al., 2014). As ES are beneficial for people and subsequently do not exist in the absence of people, they can be conceived as part of a social-ecological system. Sarkki (2017, p. 83) highlighted the complex links between ES, governance and human well-being, and promoted the “co-production of benefits for human well-being by ES and environmental governance”. Thus, governance and its structure play an important role for the provision of ES. Farhad et al. (2015), for example, have shown how changes in governance and the interplay of local-level institutions and upper level regulation affect ES. The complexity and dimensional levels of ES (Grunewald and Bastian, 2018) favour the consideration of the governance of regional planning, as it requires the interplay of state, municipal, and private sector actors (Fürst, 2004).

Here, we focus on the general question of how urban and regional land-use planning in practice and its future results (of zoning) can better consider ES. We pay special attention to the governance aspects of planning in order to answer this question. In order to understand the motives and results of planning processes, a look at the governance of land-use planning has proven useful (Nuissl and Heinrichs, 2011). Land-use planning is characterised by complex collective action constellations with various actors involved, including a variety of modes of action coordination ranging from hierarchical to negotiation-oriented forms. The governance approach enables a holistic perspective on the forms of control and action of land-use planning in view of ES integration. The interweaving with actor-centred institutionalism as research heuristic enables feedback from chosen forms of interaction with the institutional context, as well as regional spatial-structural conditions (Wahrhusen, 2021).

In this explorative study we examine two single case studies – the region of Rostock and the region of Munich. Through the analysis of the governance related to ES in these two case studies we investigate the hypothesis that ES are deemed among planning actors as means for SEAs and not considered as an instrument for cross-sectoral planning. Subsequently, we elicit potential parameters that could foster the integration of the ES concept into urban and regional planning processes. First, we describe in the method section the research design of conducting semi-structured qualitative interviews with selected interviewees. This constitutes the empirical basis of our research. Second, we give a brief overview on actor-centred institutionalism (Mayntz and Scharpf, 1995), which we use as a research heuristic to draw insights from the obtained data and to provide explanations for further interactions to foster the integration of ES in planning processes. After outlining the context of the two case study areas, we present the main findings followed by a discussion of the results. We close the paper with concluding remarks and present future research incentives.

In order to draw insights about the interactions of different actors within an institutional setting and policy environment we examine our data in light of actor-centred institutionalism (ACI, German Akteurzentrierter Institutionalismus, Mayntz and Scharpf, 1995). It is rooted in the understanding of the processes and results of policy decisions (Treib, 2015). As part of the neo-institutionalism movement, actor-centred institutionalism should not be considered as a fully developed theory, rather as a research heuristic (ibid.). It relies on the assumption that the actions of actors are not ultimately controlled, yet influenced by the institutional framework (Diller, 2013). Actor-centred institutionalism at least offers support to classify the different forms of interactions that occur between different actors with specific capabilities, both cognitive and normative orientations within a given institutional context and under given conditions of a policy environment (Scharpf, 1997). Actor-centred institutionalism is too complex to incorporate its entirety systematically in an empiric investigation (Mayntz and Scharpf, 1995). However, the importance of political science research heuristics in planning science has been recognised and discussed (Diller, 2013; Krekeler and Zimmermann, 2014). Further, actor-centred institutionalism has been described as a conceptional bridge towards governance research (Gailing and Hamedinger, 2019) and also served as a research heuristic in the context of governance analysis about land-saving settlement development (Wahrhusen, 2021).

However, this qualitative research design can by no means extensively use the full scope of actor-centred institutionalism or provide definitive explanations of the cases. Thus, we emphasise the research heuristic properties of actor-centred institutionalism while addressing the qualitative data represented in this study. Our aim is to illustrate different institutional agendas and to indicate possible adjustments beneficial for ES integration which in turn address further areas of research. That is also why we have chosen two single case studies which inform the results and bear some differences in size – with Rostock as a relatively small regional centre and bigger city, and Munich as one of the biggest German cities and economic centres – as well as in terms of its geographical location.

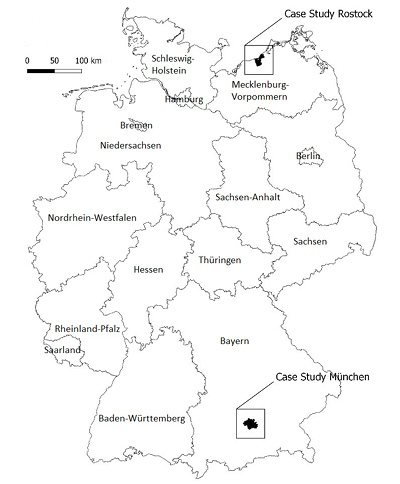

In our explorative case study design, the research focus was set to analysing the governance of urban and regional planning in the two single case studies – the region of Rostock and the region of Munich (Fig. 1). In choosing our case studies, we made sure to successively build access to the local knowledge, as well as contact opportunities with relevant stakeholders. The choice of the Munich case study was apparent as part of the research team has been working for a long time with different projects in the fields of environmental planning, spatial development, and nature conservation in and around Munich. Therefore, a good knowledge base of the region and the planning context, as well as contacts to different actors were already in place. As a counterpart, we have chosen the Rostock case study as it geographically complements the Munich case study. Rostock is located in the north of Germany, while Munich is located in the south. Here, too, part of the research team had obtained a knowledge base of the region and the planning context, as well as contacts with stakeholder prior to the research. Both case studies are characterised by an urban core of economic importance within their respective German Federal States. In order to address the regional planning perspective in these regions we included one adjacent smaller town to both case studies – the city of Bad Doberan in the fringe of Rostock and the city of Dachau near Munich. By no means did we intend to directly compare the two case studies. The explorative approach of the underlying research project endorsed the selection of two geographically different regions and within those regions the focus on one bigger and one smaller city. By choosing our case studies we aimed to gain insights about the role and value of ES among planning actors and hoped to identify parameters relevant for facilitating integrational approaches of ES into decision-making in the context of cross-sectoral urban and regional planning.

Fig. 1. Location of the case studies in Germany

Source: own work based on map data from OpenStreetMap©.

We conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews in each case study region with an average duration of one to one and a half hours. The questionnaire was developed in advance for both case studies and sent to the interviewees beforehand. It comprised different thematic blocks. These included the context of the case study region, the background of planning and decision-making processes with corresponding circumstances of governance practices of urban and regional planning, questions about relevant stakeholders and citizen participation, and questions about the ES concept, its evaluation, assessment and communication, and its ability to be integrated into the planning process. Depending on our interview partners, and their expertise and experience, we were able to delve into various thematic blocks and ask detailed questions about them. Yet other thematic blocks could only be addressed superficially depending the interviewees’ knowledge. Our passages quoted further in this paper mark key passages that we would like to reflect representatively for a thematic block. The aim of the interviews was to gain a more comprehensive insight into different phases and aspects of planning using the expertise and practical knowledge of the interviewees.

A total of nine semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted for the case study region of Munich. The interviewees included planning officials from departments for urban or regional development and planning bodies, local politicians, and civil society activists. Furthermore, six referred in their statements to Munich and three to the small adjacent town of Dachau.

For the case study region of Rostock ten interviewees participated, including planning officials from departments for urban or regional development and planning, representatives of the Chamber of Industry and Commerce, local politicians, and representatives of environmental agencies on the city, county and/or regional levels. Two interviewees referred to Bad Doberan, the smaller adjacent town near Rostock, five interviewees to the city of Rostock and 3 interviewees referred to the county of Rostock.

The participants of this study were asked to address the questions from their institutional role as experts and not as a private person. Thus, the interviewees in light of actor-centred institutionalism partly represent different institutions with diverse aims and resources, as well as partly different logics of action. While mainly – due to the matter of fact that urban and regional planning is an administrative act in Germany – administrative actors were involved, also the other logics of action were represented, such as politics, civil society, and economy. However, in accordance with data privacy regulations we cannot state the functions or positions of the individual interviewees as this would reveal their identities in such a small sample size.

Land-use planning in Germany is to a certain extend hierarchically structured, and even though all levels set the frame for spatial and land-use development, regional and urban planning are the most relevant for considering ES and having a concrete impact on the ground in terms of the final land-use structure. While land-use planning at the regional or local levels has to weigh and then integrate all interests and demands on the land, there are also more specific plans and planning endeavours, dealing with specific land-uses or concerns, such as transport, landscape, energy or agriculture. In contrast to the local level, the regional level has to co-ordinate not only those specific demands, but also the interests and demands of the local communities of a region. That is why the regional plan is legally binding to the local communities in their land-use planning. On local levels, then, cities and communities develop in the ideal case a regulatory land-use plan for their territory as a whole and out of that the development plan, which is binding to everyone. How planning has to be performed and what has to be considered in doing so, is defined in two different explicit laws, which already tackle some ES explicitly, e.g., habitat.

The subsequently presented results represent key statements of interviewees to the thematic blocks posed by the interview guidelines. These address the research objective of eliciting the role and value of ES among planning actors of the case studies in two ways: (1) general responses representing the overall planning system (governance, i.e., involved and missing actors, goals, and assertiveness of actors), and (2) the position of ES among actors in the current planning system (i.e., allocation of responsibility). Following the results separated per the case studies, Table 1 gives an overview on the summarised main findings before these are discussed in the next chapter.

In regards to the institutional setting, remarks about the priorities and goals of planning processes in the region can be drawn from the interviews. Without exception the goal of sustainable or balanced development was mentioned several times by the planning-related administration. This is also in accordance with German planning, as well as construction law claiming sustainable land-use development as the overarching goal. In addition, less surprising and expectable goals were mentioned by interviewees, who mainly referred their own remit and were partly directly related to the target program or defined goals of their institution. For example, regional planning actors referenced the corresponding regional plan, environmental agencies referred environmental quality standards as the object of consideration and assessment standard for the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), and economic representatives emphasised economic stability and development. Furthermore, interviewees mentioned the focus of urban planning in the growing city of Rostock was on securing land for building, housing and community needs, however, in reference to balanced development between ecology and social issues. Yet, the focus in the smaller municipality of Bad Doberan was on tourism without harming nature too much, heavy rainfall events and flood protection besides creating affordable housing. However, aims were referenced regarding consistent environmental compatibility of all decisions. Interestingly, in addition to economic development, the simultaneous improvement of the human well-being among the population was highlighted as another important goal by economic representatives. In general, planning efforts reflected expected outcomes of a growing region, such as land-saving goals, securing housing, and maintaining economic attractiveness, especially in tourism-rich areas. However, all objectives were mentioned in connection with environmental concerns or as a compromise between social, economic, and ecological interests.

Furthermore, formal statements were made about the institutionally supported planning processes regarding the involvement of participating actors. In general, interviewee statements named the usually involved actors in regional planning and negotiation processes. Many of the actors mentioned are required by law (public authorities, specialist agencies, public interest groups, as well as the broad public) or also addressed in addition to include all interests on land, be it social, environmental or economic interests. One person said that the formal participation with “a long list of actors” also covered all actors:

“Our list is so long. We deal with the actors who are really important. As it is in the daily routine, I’d say. And they are on our list anyway.” (R1)[1]

Or as another interviewee has put it: “[a]ll those that are legally required, of course,” (R2) are involved.

Missing actors regarding direct relevance for ES were not mentioned. Some individual statements about general missing actors in participatory processes, such as people with a migration background or those with low income, were made. However, the overall feedback about missing actors was that the usual procedure covered all relevant actors, like the statements about involved actors, or as one interviewee stated:

“I can’t think of any relevant actors off the top of my head, and I don’t know whether someone we consider relevant has not brought them in.” (R3)

In addition, the individual economic perspective, represented by local small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), was perceived as lacking, especially in the city of Rostock, although (regional) business associations or representatives were mentioned more often among the actors involved or at least addressed. It was also described that local companies only participated when concrete plans were already “on the table.” It is also worth noting that late participation was generally mentioned as problematic, i.e., not a fundamental lack of certain actors, but their late participation. Further, as planning is also a formal procedure, in a late stage of the planning process an intense involvement of those actors and their specific interests could not be assured anymore.

The interviewees described actors who were basically involved in planning as assertive in principle, since they had already gained experience and could make more references to “abstract” topics (e.g., at the level of the land-use plan). In addition, it is advantageous if actors already have access to administrative structures. Thus, there were statements that described access at an individual level, e.g., through personal contacts (e.g., to the mayor) or political networks (e.g., parliamentary groups) – as one interviewee claimed:

“These are the people who have a short line to the mayor, a short line to the parliamentary groups, who have networks of some kind, who do not even lower themselves to this level of participation from their point of view, but try to act without these processes.” (R4)

However, assertive actors were also described at a collective level, for example, through associations that had already contributed or were contributing knowledge and experience to administrative structures (e.g., environmental associations). One statement from Bad Doberan, a region characterised by tourism and health resorts, described tourism associations and rehabilitation clinics with great assertiveness:

“The tourism associations and such things are of course also important, because if we target the main tourism focus area, then of course the tourism service providers are a very, very decisive power.” (R5)

It is interesting to note here that tourism associations and rehabilitation clinics have a great deal of influence on planning processes because they account for the majority of the economic viability in Bad Doberan. Apparently, there are differences at this level with the city of Rostock, where local SMEs were often described as lacking actors. However, it is questionable whether the tourism association and the rehabilitation clinics in Bad Doberan can be described as local SMEs or whether they also act supra-regionally and thus have more power than classic local SMEs.

Alongside being described as assertive through bundling interests and engaging in political, administrative networks, environmental associations have further been described also as actors with allegedly most concern about ES. Besides being involved in planning processes for environmental issues, environmental associations were viewed as relevant actors for bringing the ES concept on the political agenda, as one interviewee stated:

“Perhaps the local group of the [environmental association] in Bad Doberan is one of those who can perhaps get the topic more into politics here. That would not be such a bad thing in the sense of this process.” (R5)

In addition, citizens, nature conservation agencies, and landscape planning entities, and, at the political level, the Green Party were also mentioned, although less frequently. Thus overall, the actors who were associated with dealing with ES in the context of planning processes by most interviewees can be summarised as environmental-oriented actors.

By contrast, the institutional environmental agency had only mentioned, in addition to specific environmental concerns, quality assurance as a priority, yet without directly referencing ES. Thus, in one known example, other actors have been instrumental in bringing environmental and open space concerns to the attention of the planning actors in Rostock. At the request of the public, the development model of the “Protection of significant environmental and open space concerns”[2] was included in the new version of the land-use plan, which, in addition to the preservation of all protected areas, also included the preservation of all allotment gardens (representing cultural ES among others) in Rostock (Hanse und Universitätsstadt Rostock, 2019). The fact that allotment gardens play an important role in future planning processes was also mentioned by some interviewees. Thus, even though environmental agencies are focused on environmental protection and the environmental interests are superficially included in the overarching goal of sustainable development of urban and regional planning (i.e., integrating social, economic, and environmental concerns), the public, with a strong interest in allotment gardens, managed to highlight green spaces as a major concern for future planning processes in Rostock. Perhaps this example suggests that currently ES or, in a broad sense, environmental concerns related to public interests are in the hands of the public (and politics) or at the fringe responsibility of environmental associations.

Additionally, expertise and administrative responsibility were mentioned as factors of actors relevant for planning and the environment that force assertiveness. Public interest groups can affect planning outcomes by involving expert opinions and expertise on certain matters. Thus, for example as mentioned by interviewees, environmental authorities are in a position to enforce environmental concerns through expert reports during the planning process. Conversely, as has been generally stated by interviewees, competence determines assertiveness. However, if this is true, in real-world planning procedures it is debatable as otherwise ecological and environmental concerns would be much more prominent in every day planning and the public discussions about polluting and ecosystem harming construction projects in Germany would not take place.

Interview statements give insights into assertiveness and involved actors in the planning process within an institutional setting, and ascribe the potential responsibility of ES to environmental-oriented actors. However, direct responsibilities for the integration of ES cannot be made as responsibility is neither formally assigned nor distributed among planning actors, as one interviewee described:

“That is a very fundamental question: Who bears the responsibility? Who records, who spends the money, who evaluates? And then there is also the question of how this flows into any procedures.” (R1)

Overall, the planning process seems to consider all relevant stakeholders as far as interviewees reported. ES were mainly ascribed in the case study region of Rostock as part of the potential jurisdiction of environmental agencies or institutions. However, no direct responsibilities nor possible resources of entities as integrational tools were mentioned. Thus, it indicated, based on interview statements, a lack of current responsibility to integrate the concept of ES into the planning procedure as a measurement for improving human well-being, but a seeming allocation towards environmental agencies as potential jurisdiction. Nevertheless, factors that strengthen assertiveness can be derived from the interview statements. Associations around certain interests, e.g., environmental or business associations, connections to policy or planning networks, and overall actors with knowledge about administrative structures and the general planning process were mentioned as assertive factors.

In regards to the institutional setting, remarks about the priorities and goals of planning processes in the region can be drawn from the interviews. Overarching priority issues in the case study region of Munich were the high growth pressure in the region, which could be seen in the rising population figures, the high influx into the region, and the associated challenges with regards to the design of the infrastructure. Above all, this includes saving land in the region. Issues surrounding traffic and mobility play an important role, too: Dachau was described by the interviewees as a mobility hub, which is why a traffic turnaround was urgently needed. Munich also featured increasing traffic congestion as an important issue; a better design of local public transport and the expansion of public infrastructure seemed to be necessary. It is interesting to note here that the interviewees from Munich indicated that the issue of transport had fallen on the defensive due to the dominant housing problem. Important environmental issues in the case study region of Munich were ostensibly related to the conflict between the protection of natural areas and the needs of people seeking recreation. Protection was also mentioned by the interviewees as an important environmental concern. This referred to, for example, the protection of species and biotopes, groundwater protection, noise protection, nature conservation, and the preservation of fresh air corridors. The interviewees from Dachau emphasised the role of the “Dachauer Moos” (a fen landscape north of Munich), which is a typical regional landscape feature that has been severely lost in some parts. Biodiversity and ecological connectivity were also mentioned as important environmental concerns for the region. However, in all the statements, there were hardly any direct references to ES.

Here, too, it is noticeable that the interviewees named goals related primarily to their own area of responsibility and, in some cases, were directly related to the target program or the defined goals of their institution. For example, representatives of regional planning entities have referred to the concerns that affect the region, such as the topics of settlement, free space, and traffic. Representatives of the urban planning generally referred to the negotiation processes between different, sometimes contradictory, concerns that were typical of a large city like Munich. Local politicians referred in their statements to their membership to their parliamentary parties. The reference to the corresponding institutions of the interviewees became clearest when they were asked about the actors involved in the planning and decision-making processes or who were not involved or not sufficiently involved. Here, hardly any information regarding the participation of different actors could be gained from the interview material for the case study region of Munich. Some results, though, were obtained regarding possible governance structures, which are presented subsequently.

Overall, the answers given by the interviewees regarding possible governance structures hardly enabled us to draw any conclusions about governance constellations or informal coordination possibilities. On the one hand, this was due to the sensitive nature of the question and, on the other, to the tendency of the interviewees to refer to existing formal guidelines of their institutions when answering such questions. Nonetheless, it was possible to obtain some statements in this regard. From the interview material of the case study region of Munich, we were able to identify various factors that, according to the interviewees, strengthen one’s own assertiveness. These include one’s own network and (personal) relationships with relevant actors, direct contact with decision-makers, and the opportunity to participate in various committees or networks.

‟But it happens, yes, people pick out our phone number and, yes [laughs], you can say, then harass us in the office. Yes. It happens.” (M1)

The interviewees mentioned that these factors enabled them, on the one hand, to ask for and disseminate informal opinions at an informal level. On the other, to exert influence at the informal level had a favourable effect on the acceptance of the topics that one wanted to set. Another aspect that was mentioned by the interviewees was the timing of the participation or action of the actors. The interviewees emphasised that it was only possible to set one’s own agenda if there was early participation in the decision-making process possible, meaning before the issues had been decided. At a later stage, the interviewees emphasised, it was basically no longer possible to change the existing agenda[3].

“And accordingly, we have the opportunity to suggest certain points as early as possible, already on an informal level, to point out conflicts and needs from the point of view of the environment. If this is not possible, then only in later procedures with the problem that then often some things are simply already set, which are difficult to turn around again.” (M2)

Therefore, it can be concluded from the interviews that early participation and early influence in relevant processes can be seen as a prerequisite for one’s own assertiveness. The interviewees also made statements about their procedures, which could have had a favourable effect on their own assertiveness. For example, regular coordination was the foundation of one’s own approach. The importance of exchange and interaction in all directions was also emphasised, as was a results-oriented approach and, somewhat related, an efficient and pragmatic choice of topics. The way of arguing could also have a beneficial effect on one’s ability to assert oneself. Becoming part of the agenda, emphasised by an interviewee from Dachau, worked via monetisation or the reference to economic figures. Another interviewee indicated that it could be helpful to broaden the range of concerns in an argument. Finally, binding requirements such as laws were mentioned, which could be seen as an enhancer of one’s own assertiveness and thus binding formal requirements facilitate cooperation because they leave little or no room for interpretation.

“And that, of course, is also an enrichment, that one can stand up and say, dear people, that’s the way it is, we can’t go over it in the consideration, but that has to be complied with.” (M2)

In addition to the factors that strengthen one’s own assertiveness, we asked our interviewees also about assertive actors, and the reasons for it. The following answers were obtained and compiled from the interview material. The interviewees emphasised that actors with common interests who organise themselves were considered to be assertive. As examples they mentioned clubs, associations or sponsors that organised or established for themselves.

“It’s probably easier for the [actors] who have the best personal contact with the individual city councilor. Or probably also for those actors whose overlap of members of the party or faction is greatest with the conviction they represent. I’ll say now, for example, the influence of [environmental association] is greater in the Green faction than in the [conservative] faction.” (Int: M3)

In this context, environmental and nature conservation associations were frequently mentioned. Furthermore, actors with a strong lobby and thus strong possibilities to influence decision-makers were rated as assertive. Environmental associations were also mentioned. Additionally, ES were often related to environmental concerns and thus ascribed to these environmental-oriented actors, as one interviewee phrased:

“The ‘real advocates’ of nature, species and climate protection concerns are of course the nature conservation associations.” (M4)

Finally, actors who – from their institutional position – had decision-making power were characterised as assertive. As examples, the interviewees listed political decision-makers, such as mayors, city councils or city politicians. In this context, and less surprisingly, those actors who had the best individual contact with their individual city councillor or who had the greatest overlap in terms of content in their topics were also defined as assertive.

“I have a direct line to the mayors and the relevant administrations. All it takes is one phone call, and I’m basically there. Of course, the larger the municipality, the more difficult it is.” (M4)

From the interview material, it was also possible to identify possible multipliers that had a beneficial effect on one’s own assertiveness. The interviewees named the professionalism, personal appearance, and the personal knowledge of those involved as relevant factors that had a reinforcing effect on their own assertiveness. Furthermore, actors who had a good political connection to the relevant decision-makers were defined as being assertive. In addition to these points that can be specifically assigned to actors, two aspects were also mentioned that were related to the actors’ working methods. First, a practiced approach of actor groups was classified as a reinforcing factor. For example, the urban planning of Dachau has been mentioned, which, according to the interviews, is characterised by its good, practiced way of working. At the same time, it was named as a reinforcing factor if the concerns of actors could be made visible in public space, for example with the help of citizen initiatives or citizen participation.

| Case study: Region of Rostock | Case study: Region of Munich | |

|---|---|---|

| Priorities and goals related to the planning results |

Majority: sustainable and balanced development; compromising social, economic and environmental interests Single sector-related goals, economic goals linked to improvement of human well-being depending on state of environment Urban planning securing land for building, (affordable) housing and community needs Small town specifics: flood protection, tourism development without excessive harm to nature |

Overarching priority issues: growth pressure in the region, high influx, land scarcity, housing shortage, ecological connectivity, conversation of biodiversity General issues: conflicts over commercial land, residential land and green space; conflicts between protection of natural areas and the need for recreation Small town specifics: independence of the city of Dachau as an urban body in the dynamics of the Munich metropolitan region, question of how an urban body can be maintained and how it can be preserved from urban sprawl |

| Involved actors | Long list of actors as legally required | Long list of actors as legally required |

| Missing actors |

Low income and migration households Small and medium-sized enterprises Late involvement of some actors as a problem |

Late involvement of some actors as a problem Stakeholders or persons who do not have a lobby or are not visible in the public sphere or in the public discourse |

| Assertive actors with regards to the influence on the planning results |

Stakeholders who are already very familiar with the planning process Persons with strong personal contacts in local politics Associations (e.g. tourism environmental) Strong economic actors, especially in small towns Competence and expertise: administration such as environmental administration through bringing highlighted external expertise in the process |

Stakeholders who are already very familiar with the planning process and know each other personally Persons with strong personal contacts in local politics, especially those who have decision-making authority, or in planning processes Associations (e.g. environmental) Competence and expertise: administration such as environmental administration through bringing highlighted external expertise in the process |

| Actual current responsibilities for ES |

No clearly attributed responsibilities to ES: dispersed among different sectoral administrations that have ES not explicitly as their responsibility (as, e.g., environmental administration)

Local public/citizens bringing urban green spaces (allotment gardens) strongly in the planning process |

No clearly attributed responsibilities to ES: dispersed among different sectoral administrations that have ES not explicitly as their responsibilities |

| Attributed responsibilities of actors for ES in the (near) future |

Environmental associations Nature-related administrations, especially landscape Planning and nature protection Green Party |

Environmental associations Nature-related administrations Planning and nature protection |

Before we start discussing the results, we shall reflect upon the study design, as well as on limitations in performing the interviews. The unique research design of including a large city and an adjacent smaller city in two different case studies is beneficial for this abductive research approach. However, this also holds caveats. For example, the interview enquiry returned in the larger cities more interview partners than in the smaller ones because in the larger cities potentially more interview partners were available. Further, larger cities often exert powers financially (and culturally), dominating and highly influencing developments in their nearby regions. Thus, interviews might overrepresent perspectives dominated by the development processes in larger cities. Additionally, the conducting of the interviews was affected by the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, and thus no fieldtrips or face-to-face interviews nor direct participation in planning discussions were possible. For further research proposals, ethnographic and participatory methods could supplement the data. We discuss the results along the two identified main subtopics: (a) responsibilities towards ES in the land-use planning system, and (b) governing human well-being through governing ES.

The interviews raise questions about the responsibility for ES within the planning procedure and gave insights regarding properties that could contribute to improving the assertiveness of the involved actors. In general, over both case study regions, the planning process was described as including every relevant actor, so that no missing actors relevant for ES integration were apparent. However, explicitly mentioned among the interviews in Rostock, none of the actor institutions have been accounted as being responsible for the integration of ES yet mostly the responsibility for ES was ascribed by interviewees towards environmental-oriented actors, i.e., environmental or nature conservation administration or respective associations. This represents an approach to integrating ES into the planning practice. For example, Heiland et al. (2016) and Grunewald and Bastian (2018) have described the relevance of ES for nature conservation and, therefore, referred to landscape planning, representing specialist planning relevant to nature conservation in Germany, as the adequate instrument to integrate the matter of ES into the general land-use planning process. However, landscape planning has its limitations covering explicitly all potential ES, such as many provisioning services, as well as some regulating services. The integration of a broad spectrum of different ES would, if we look at the planning system in Germany at least, have to be dispersed to the responsibility of different specific planning endeavours and administrative units (also at different levels). Or perhaps certain ES are not even covered by any administrative units. It is within the process of general land-use planning to cut across all those different sectors and specified interests on land and land-use and to bring them together and weight those interests in order to arrive at a cross-sectoral common land-use decision in the final plan (Scholles, 2008, p. 309ff.). Thus, even though environmental concerns might be integrated into the planning process through the landscape plan, these concerns might not pass this weighing decision of general cross-sectoral land-use planning which has to weigh those environmental concerns against all the other interests on land-use – in growing cities those are, among others, predominantly housing, economic, and related transport concerns.

The overall qualities of ES are the contributions to human well-being; though the concept of ES promotes general environmental concerns, these interests cannot solely cover the whole scope of ES. Especially in urban areas where land is scarce, ES must be integrated exceeding arguments only about environmental concerns. Thus, to unfold the full potential of ES in urban and regional planning, integration of ES should be addressed towards human well-being. This could shift ES from a nature conservation perspective to a cross-sectoral human well-being perspective and thus responsibility shifts from landscape planning towards city regional planning. Thorén and Stålhammar (2018) explored the ES concept in a comparison to economic dominance highlighting the early attempts to integrate ES into decision-making through strict economic terms. Even though the (scientific) development of ES has broadened since then, including multiple values, they questioned the magnitude of the changes of perspective: “However, it is unclear to what extent this apparent shift involves a substantive change in perspective and a departure from a conventional economics framework, and the challenges associated with such a framework” (Thorén and Stålhammar, 2018, p. 2). Residue economic values were also mentioned in Munich to the extent that monetarisation would apparently strengthen the ES concept in planning processes.

In order to bridge sectoral and administrative borders among different planning interests and authorities to implement ES, some scholars have proposed to create or facilitate organisations or actors who can act and navigate across sectors and scales (Droste et al., 2017; Andersson et al., 2014; Ernstson et al., 2010). Interviewees did not directly mention scale-crossing brokers (Ernstson et al., 2010), yet the importance of networks and contacts was mentioned. Thus, the establishing brokers in the case study regions might prove beneficial for integrating ES into the existing planning system. However, this would not only bear costs (in terms of personnel and facilities) but would also interfere with, as subsequently highlighted, a rigid planning system where an overall notion of “no actors are missing” prevails. Also, especially for regional planning, financial means are already not in all regions broadly distributed in Germany (depending on the federal state which organises the regions and respectively the regional planning finances). It is difficult to imagine how those brokers could be financed at all.

Derived from the interviews, the planning system can be understood as a fundamental, strict, all-encompassing, and trusting institutional system. Understandably, the actors pursue the institutionally established goals and use the institutionally established processes that are perceived as comprehensive. This is reflected in the statements that all relevant stakeholders are also involved in the planning process through legally binding instruments. However, it is also clear that the institutional goals are very specific (i.e. reconciling residential and commercial attractiveness with land saving goals in a growing region) and that there are no stakeholders who specifically pursue ES as a holistic concept. The overarching prescription of sustainable spatial development (i.e. combining social, environmental, and economic concerns) is also evident in the interviews, but again very specific: environmental actors are responsible for environmental concerns, and economic actors for economic ones. A holistic view of the task of sustainable land-use planning under the uniform goal of preserving and improving the quality of life for people, as is attempted to be communicated with the ES concept, is not yet incorporated into the specifically oriented planning structure, at least in the two case studies presented here. It seems that the institutional structures of the planning process cannot yet encompass holistic approaches such as ES. Integration at this point must happen through individual actors who are aware of the importance of the functioning of ecosystems on human well-being, as Longato et al. (2021, p. 82) stated in their literature review: “In most of the analysed case studies, ES integration occurred because of the commitment of policy-makers and stakeholders and their high awareness of ES importance. This need for a ‘fertile ground’ suggests limitations to the conceptual use of ES as the entry point to promote environmental awareness and pro-environmental attitudes, at least within spatial planning processes”. Thus, it is necessary to develop approaches to integrate ES into the planning process beyond the commitment of single pro-environmental individuals.

As planning only prepares, though intensively, the final political decisions on future land-use, it cannot be land-use planning alone that establishes ES as a common argumentative basis for decision-making. Moreover, the ES concept also has to be promoted within politics and society more intensively to raise further awareness and to potentially set weighing differently in the planning process, as well as in the final land-use decisions. The fact that the political will, and the underlying societal will, are important prerequisites for integrating ES into the planning process was also a strong point made by different interviewees, and that also reflected opinions from the literature (Grêt-Regamey et al., 2017; Runhaar et al., 2009).

Dealing with the complex and often unknown interrelations within social-ecological systems and the multiple values addressed at ES and the multiple actors benefiting and contributing to ES demands a multi-level governance approach with an effective science-policy interface and participatory and adaptive processes (Newig, 2011; Loft et al., 2015; Mann et al., 2015; Spyra et al., 2020). Furthermore, we argue that an institutional change of perspective (as described above) is needed to lay the foundations for adaptive and integrative governance for ES in cross-sectoral urban and regional planning. ES must be discussed as benefitting human well-being in a holistic approach, thus exceeding the apparent view (as expressed in the interviews) in the planning practice as environmental concern in need of economic valuation – setting an argumentative baseline in weighing decisions for ES as a foremost contribution to sustainable human well-being furthering ES integration into the planning process.

However, the caveat of this explorative study is that we could not empirically test the change of perspective, neither develop tools in order to facilitate this change. Nonetheless, through close engagement of the research project with planning practitioners we hope to have influenced and stimulated a change of perspective that might induce a transformative pathway from actor to institution. Often an iterative science-policy process or science-policy interface has been mentioned in the literature to foster and promote ES uptake into planning and decision-making (Görg et al., 2016; Kettunen et al., 2017; Ruckelshaus et al., 2015; Loft et al., 2015). Further, properties of assertiveness within the planning process were mentioned by interviewees, which might help develop future strategies to successfully integrate ES in the local planning system through engaging in the governance of ES (Table 1). Additionally, Farhad et al. (2015, p. 100) has emphasised “the strategic importance of local-level institutions” for the transformation of governance systems for the successful management of ES, yet acknowledging that top-down structures complement the process. All these notions could potentially affect pathways towards integrating ES into the planning system (Fig. 1).

The complex links between human well-being and the social-ecological system of ES and governance have been emphasised by Sarkki (2017, p. 83) by promoting the “co-production of benefits for human well-being by ES and environmental governance.” However, how far human well-being is prioritised currently in the planning system and not equated with economic stability remains debatable. Nevertheless, in view of the striking effects of climate change and the need for resilient cities safeguarding human well-being for future events becomes indispensable.

Fig. 2. Overall representation of efforts that could potentially foster the integration of ecosystem services (ES) into urban and regional planning. Focus of this research relates to the integration pathway (red arrow) where the benefits for human well-being are perceived as the most relevant factors for integration as they stimulate cross-sectoral planning efforts. The more conventional pathway (grey arrow) is to include ES as means for environmental concerns (i.e, nature conservation) or with economic terms (i.e., monetarisation)

Source: own work.

| Factors | Example | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Time of participation | “And accordingly, we have the opportunity to suggest certain points as early as possible, already on an informal level, to point out conflicts and needs from the point of view of the environment. If this is not possible, then only in later procedures with the problem that then often some things are simply already set, which are difficult to turn around again.” (M2) | Early involvement and raising of the relevant topic seems to be beneficial for successful integration into the planning process with later consideration of implementation. |

| Network | “These are the people who have a short line to the mayor, a short line to the parliamentary groups, who have networks of some kind, who do not even lower themselves to this level of participation from their point of view, but try to act without these processes.” (R4) | Close connections to decision-makers or planning actors and creating a network of planning-related relationships fosters recognition of certain issues or ideas. |

| Revealing the stakes | “And that, of course, is also an enrichment, that one can stand up and say, dear people, that’s the way it is, we can’t go over it in the consideration, but that has to be complied with.” (M2) | This can relate to a top-down approach where, for example, certain laws or policies require certain actions. However, this can also relate to bottom-up approaches where society pressures certain issues on the political agenda. Further, at an individual level, involvement and ownership might be created through small, local projects (i.e., examples of best practice) or consternation towards the broader public is expanded through campaigning. |

| Organizing interest | “Perhaps the local group of the [environmental association] in Bad Doberan is one of those who can perhaps get the topic more into politics here. That would not be such a bad thing in the sense of this process.” (R5) | Individual matters are difficult to include in an overall planning matter. Thus, an organisation of individuals advocating for specific interests, e.g., in associations, exercises more pressure on the political and planning system. |

Ecosystem services in urban and regional planning have influenced and fostered practice-oriented scientific discourses in recent years thus resulting in insights about the assessment and valuation of ES, as well as the opportunities and barriers of ES integration. However, practical implementation in real-world cross-sectoral planning systems has yet remained scarce – especially in Germany. Therefore, this research focuses on the role and value of ES among planning actors in two case studies in Germany in a desire to identify relevant parameters to facilitate integrational approaches. This explorative research has revealed a disciplinary and all-encompassing planning system in which the issue of ES integration is mostly relatable to the remit of environmental oriented actors (i.e., environmental administration or associations), yet without clearly attributing responsibilities. Thus, the sectoral structure of the planning system professes no allocation, let alone responsibility for ES except as a potential adjunct to environmental concerns, fostering and reinforcing a selective perspective on ES as environmental or economic means. However, factors of assertiveness can be drawn from the interview statements, e.g., early involvement of actors about a certain issue in the planning process is beneficial for success or maintaining networks with close relationships to decision-makers and planners (Table 2). In addition to other scientifically discussed approaches like science-policy interfaces and the combination of top-down and bottom-up incentives, these factors could contribute to a more intense and all-encompassing uptake of ES into the planning systems (Fig. 2). However, in order to unfold the full potential of ES, we argue for a change of the perspective on the objective of integrating ES within the planning practice – away from the sectoral perspective of ES as an environmental concern or economic benefit. The fact of addressing ES as an important means towards improving human well-being potentially shifts the ES concept from a sectorally perceived and attributed endeavour, i.e., environment-related, to an integrative cross-sectoral land-use planning endeavour.

Acknowledgements. This paper presents the outcomes of the ÖSKKIP research project. The ÖSKKIP acronym in German stands for “Ecosystem Services of Urban Regions – Mapping, Communicating, and Integrating into Planning to conserve biodiversity during a changing climate” (in German: „Ökosystemleistungen von Stadtregionen – Kartieren, Kommunizieren und Integrieren in die Planung zum Schutz der biologischen Vielfalt im Klimawandel“). The authors would like to thank the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research for funding this project within the framework of the Strategy “Research for Sustainability” (FONA, http://www.fona.de/en/) under the funding code 16LC1604A/CU, as well as the interviewees for their time and insights.

ANDERSSON, E., BARTHEL, S., BORGSTRÖM, S., COLDING, J., ELMQVIST, T., FOLKE, C. and GREN, Å. (2014), ‘Reconnecting cities to the biosphere: stewardship of green infrastructure and urban ecosystem services’, Ambio, 43 (4), pp. 445–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-014-0506-y

ARKEMA, K. K., ABRAMSON, S. C. and DEWSBURY, B. M. (2006), ‘Marine ecosystem-based management: from characterization to implementation’, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 4 (10), pp. 525–532. https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2006)4[525:MEMFCT]2.0.CO;2

BREUSTE, J. (2019), Die Grüne Stadt, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

BURKHARD, B., KANDZIORA, M., HOU, Y. and MÜLLER, F. (2014), ‘Ecosystem service potentials, flows and demands-concepts for spatial localisation, indication and quantification’, Landscape Online, 34, pp. 1–32. https://doi.org/10.3097/LO.201434

CONNOLLY, J. J. T., SVENDSEN, E. S., FISHER, D. R. and CAMPBELL, L. K. (2014), ‘Networked governance and the management of ecosystem services: The case of urban environmental stewardship in New York City’, Ecosystem Services, 10 (1), pp. 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.08.005

DEPPISCH, S., GEISSLER, G., POSSER, C. and SCHRAPP, L. (2021), ‘Approaches to integrate ecosystem services in formal spatial planning’, Raumforschung und Raumordnung | Spatial Research and Planning. Online first. https://doi.org/10.14512/rur.66

DEPPISCH, S., HEITMANN, A., SAVASCI, G. and LEZUO, D. (2022), ‘Ecosystem services in urban and regional planning instruments’, Raumforschung und Raumordnung | Spatial Research and Planning. Online first. https://doi.org/10.14512/rur.122

DILLER, C. (2013), ‘Ein nützliches Forschungswerkzeug! Zur Anwendung des Akteurzentrierten Institutionalismus in der Raumplanungsforschung und den Politikwissenschaften’, pnd|online, 1.

DROSTE, N., SCHRÖTER-SCHLAACK, C., HANSJÜRGENS, B. and ZIMMERMANN, H. (2017), ‘Implementing nature-based solutions in urban areas: financing and governance aspects’, [in:] KABISCH N., KORN, H., STADLER J. and BONN, A. (eds.). Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56091-5_18

ERNSTSON, H., BARTHEL, S., ANDERSSON, E. and BORGSTRÖM, S. T. (2010), ‘Scale-crossing brokers and network governance of urban ecosystem services: the case of Stockholm’, Ecology and Society, 15 (4), https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03692-150428

EUROPÄISCHE METROPOLREGION MÜNCHEN e.V. (n.d.), Wirtschaftsstandort Metropolregion München, available online at: https://www.metropolregion-muenchen.eu/region/wirtschaftsstandort/ [accessed on: 20.09.2021].

FARHAD, S., GUAL, M. A. and RUIZ-BALLESTEROS, E. (2015), ‘Linking governance and ecosystem services: The case of Isla Mayor (Andalusia, Spain)’, Land Use Policy, 46 (1), pp. 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.01.019

FORKINK, A. (2017), ‘Benefits and challenges of using an Assessment of Ecosystem Services approach in land-use planning’, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 60 (11), pp. 2071–2084. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2016.1273098

FÖRSTER, J., BARKMANN, J., FRICKE, R., HOTES, S., KLEYER, M., KOBBE, S., KÜBLER, D.,RUMBAUR, C., SIEGMUND-SCHULTZE, M., SEPPELT, R., SETTELE, J., SPANGENBERG, J. H., TEKKEN, V., VÁCLAVÍK, T. and WITTMER, H. (2015), ‘Assessing ecosystem services for informing land-use decisions: a problem-oriented approach’, Ecology and Society, 20 (3). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07804-200331

FÜRST, D. (2004), ‘Regional Governance’, [in:] BENZ, A. (eds). Governance – Regieren in komplexen Regelsystemen, Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 45–64.

GAILING, L. and HAMEDINGER, A. (2019), ‘Neoinstitutionalismus und Governance’ [in:] WIECHMANN, T. (eds). ARL Reader Planungstheorie Band 1, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 167–354.

GENELETTI, D., CORTINOVIS, C., ZARDO, L. and ADEM ESMAIL, B. (2020a), ‘Conclusions’ [in:] GENELETTI, D., CORTINOVIS, C., ZARDO, L. and ADEM ESMAIL, B. (eds.). Planning for Ecosystem Services in Cities, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 67–72.

GENELETTI, D., CORTINOVIS, C., ZARDO, L. and ADEM ESMAIL, B. (eds) (2020b), Planning for Ecosystem Services in Cities, Cham: Springer International Publishing.

GÓMEZ-BAGGETHUN, E. and BARTON, D. N. (2013), ‘Classifying and valuing ecosystem services for urban planning’, Ecological Economics, 86, pp. 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.08.019

GÖRG, C., WITTMER, H., CARTER, C., TURNHOUT, E., VANDEWALLE, M., SCHINDLER, S., LIVORELL, B. and LUX, A (2016), ‘Governance options for science–policy interfaces on biodiversity and ecosystem services: comparing a network versus a platform approach’, Biodiversity and Conservation, 25 (7), pp. 1235–1252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1132-8

GRÊT-REGAMEY, A., ALTWEGG, J., SIRÉN, E. A., VAN STRIEN, M. J. and WEIBEL, B. (2017), ‘Integrating ecosystem services into spatial planning – A spatial decision support tool’, Landscape and Urban Planning, 165 (10), pp. 206–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.05.003

GRUNEWALD, K. and BASTIAN, O. (2018), ‘Ökosystemdienstleistungen’ [in:] ARL – Akademie für Raumforschung und Landesplanung (eds.). Handwörterbuch der Stadt- und Raumentwicklung, Hannover: ARL – Akademie für Raumforschung und Landesplanung, pp. 1677–1683.

HANSE- UND UNIVERSITÄTSSTADT ROSTOCK (2019), Neuaufstellung des Flächennutzungsplans (FNP) der Hanse- und Universitätsstadt Rostock. Festlegung des Untersuchungsrahmens (Scoping), https://i-k-rostock.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/19-08-21-FNP-2019.pdf [accessed on: 20.09.2021].

HANSE- UND UNIVERSITÄTSSTADT ROSTOCK (2020), Statistische Nachrichten. Neue Bevölkerungsprognose bis 2035, https://rathaus.rostock.de/media/rostock_01.a.4984.de/datei/_Bericht%20Bev%C3%B6lkerungsprognose%202020.pdf [accessed on: 20.09.2021].

HEILAND, S., KAHL, R., SANDER, H. and SCHLIEP, R. (2016), ‘Ökosystemleistungen in der kommunalen Landschaftsplanung – Möglichkeiten der Integration’, Naturschutz und Landschaftsplanung, 48 (10), pp. 313–320.

KACZOROWSKA, A., KAIN, J.-H., KRONENBERG, J. and HAASE, D. (2016), ‘Ecosystem services in urban land use planning: Integration challenges in complex urban settings – Case of Stockholm’, Ecosystem Services, 22 (2), pp. 204–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.04.006

KETTUNEN, M., BRINK, P. T., MUTAFOGLU, K., SCHWEITZER, J.-P., PANTZAR, M., CLARET, C., METZGER, M. and PAVLOVA, D. (2017), Making green economy happen: Integration of ecosystem services and natural capital into sectoral policies. Guidance for policy- and decision-makers, https://oppla.eu/sites/default/files/uploads/kettunen-et-al-2017-guidance-ecosystem-service-policy-integration-final.pdf [accessed on: 30.09.2021].

KOWARIK, I., BARTZ, R., BRENCK, M. and HANSJÜRGENS, B. (2017), Ökosystemleistungen in der Stadt. Gesundheit schützen und Lebensqualität erhöhen: Kurzbericht für Entscheidungträger, Leipzig: Naturkapital Deutschland – TEEB DE.

KREKELER, M. and ZIMMERMANN, T. (2014), Politikwissenschaftliche Forschungsheuristiken als Hilfsmittel bei der Evaluation von raumbedeutsamen Instrumenten, Hannover: Akademie für Raumforschung und Landesplanung.

LANDKREIS ROSTOCK (n.d.), Wirtschaft und Verkehr, https://www.landkreis-rostock.de/regionales/wirtschaft_verkehr/ [accessed on: 20.09.2021].

LOFT, L., MANN, C. and HANSJÜRGENS, B. (2015), ‘Challenges in ecosystem services governance: Multi-levels, multi-actors, multi-rationalities’, Ecosystem Services, 16 (4), pp. 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.11.002

LONGATO, D., CORTINOVIS, C., ALBERT, C. and GENELETTI, D. (2021), ‘Practical applications of ecosystem services in spatial planning: Lessons learned from a systematic literature review’, Environmental Science & Policy, 119, pp. 72–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.02.001

LUEDERITZ, C., BRINK, E., GRALLA, F., HERMELINGMEIER, V., MEYER, M., NIVEN, L., PANZER, L., PARTELOW, S., RAU, A.-L., SASAKI, R., ABSON, D. J., LANG, D. J., WAMSLER, C. and WEHRDEN, H. VON (2015), ‘A review of urban ecosystem services: six key challenges for future research’, Ecosystem Services, 14 (2), pp. 98–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.05.001

MANN, C., LOFT, L. and HANSJÜRGENS, B. (2015), ‘Governance of Ecosystem Services: Lessons learned for sustainable institutions’, Ecosystem Services, 16 (4), pp. 275–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.11.003

MASCARENHAS, A., RAMOS, T. B., HAASE, D. and SANTOS, R. (2014), ‘Integration of ecosystem services in spatial planning: a survey on regional planners’ views’, Landscape Ecology, 29 (8), pp. 1287–1300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-014-0012-4

MAYNTZ, R. and SCHARPF, F. W. (1995), ‘Der Ansatz des akteurzentrierten Institutionalismus’, [in:] MAYNTZ, R. and SCHARPF, F. W. (eds). Gesellschaftliche Selbstregelung und Steuerung, Frankfurt am Main: Campus, pp. 39–72.

MEA – MILLENNIUM ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (2005), Ecosystem and Human Well-being. Synthesis, Washington DC.

NEWIG, J. (2011), ‘Partizipation und neue Formen der Governance’, [in:] GROSS, M. (eds.), Handbuch Umweltsoziologie, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften | Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, pp. 485–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-93097-8_23

NUISSL, H. and HEINRICHS, D. (2011), ‘Fresh Wind or Hot Air – Does the Governance Discourse Have Something to Offer to Spatial Planning?’ Journal of Planning Education and Research, 31 (1), pp. 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X10392354

PLANUNGSVERBAND ÄUSSERER WIRTSCHAFTSRAUM MÜNCHEN (2019), Landeshauptstadt München. Ausführliche Datengrundlage 2017, https://www.pv-muenchen.de/fileadmin/Medien_PV/Leistungen/Daten_und_Studien/Kreisdaten/LKR_Datengrund_2017/LHM_Datengrund_2017_Broschuere_frei.pdf [accessed on: 20.09.2021].

PLANUNGSVERBAND REGION ROSTOCK (2020), Die Region Rostock – Fakten, https://www.planungsverband-rostock.de/region/fakten/ [accessed on: 20.09.2021].

POTSCHIN-YOUNG, M., BURKHARD, B., CZÚCZ, B. and SANTOS-MARTÍN, F. (2018), ‘Glossary of ecosystem services mapping and assessment terminology’, One Ecosystem, 3. https://doi.org/10.3897/oneeco.3.e27110

PRIMMER, E. and FURMAN, E., (2012), ‘Operationalising ecosystem service approaches for governance: Do measuring, mapping and valuing integrate sector-specific knowledge systems?’ Ecosystem Services, 1 (1), pp. 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2012.07.008

REGIONALER PLANUNGSVERBAND MÜNCHEN (n.d.), Region München, https://www.region-muenchen.com/der-rpv/region [accessed on: 20.09.2021].

RUCKELSHAUS, M., MCKENZIE, E., TALLIS, H., GUERRY, A., DAILY, G., KAREIVA, P., POLASKY, S., RICKETTS, T., BHAGABATI, N., WOOD, S. A. and BERNHARDT, J. (2015), ‘Notes from the field: Lessons learned from using ecosystem service approaches to inform real-world decisions’, Ecological Economics, 115 (14), pp. 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.07.009

RUNHAAR, H., DRIESSEN, P. P. J. and SOER, L. (2009), ‘Sustainable Urban Development and the Challenge of Policy Integration: An Assessment of Planning Tools for Integrating Spatial and Environmental Planning in the Netherlands’, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 36 (3), pp. 417–431. https://doi.org/10.1068/b34052

SARKKI, S. (2017), ‘Governance services: Co-producing human well-being with ecosystem services’, Ecosystem Services, 27 (1), pp. 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.08.003

SCHARPF, F. W. (1997), Games Real Actors Play: Actor-Centered Institutionalism in Policy Research, Boulder: Westview.

SCHOLLES, F. (2008), ‘Abwägung, Entscheidung’, [in:] FÜRST, D. and SCHOLLES, F. (eds.). Handbuch Theorien und Methoden der Raum- und Umweltplanung, Dortmund: Rohn, pp. 309–312.

SPYRA, M., LA ROSA, D., ZASADA, I., SYLLA, M. and SHKARUBA, A. (2020), ‘Governance of ecosystem services trade-offs in peri-urban landscapes’, Land Use Policy, 95 (2), 104617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104617

STATISTISCHES AMT MECKLENBURG-VORPOMMERN (2021), Bevölkerung nach Alter und Geschlecht in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Teil 2: Gemeindeergebnisse 2020. Schwerin, https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/MVHeft_derivate_00005345/A133G%202020%2000.pdf [accessed on: 20.09.2021].

TERZI, F., TEZER, A., TURKAY, Z., UZUN, O., KÖYLÜ, P., KARACOR, E., OKAY, N. and KAYA, M. (2020), ‘An ecosystem services-based approach for decision-making in urban planning’, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 63 (3), pp. 433–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2019.1591355

THORÉN, H. and STÅLHAMMAR, S. (2018), ‘Ecosystem services between integration and economics imperialism’, Ecology and Society, 23 (4). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10520-230444

TREIB, O. (2015), ‘Akteurzentrierter Institutionalismus’ [in:] WENZELBURGER, G. and ZOHLNHÖFER, R. (eds.), Handbuch Policy-Forschung, Wiesbaden, Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, pp. 277–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-01968-6_11

UNEP (2014), Integrating Ecosystem Services in Strategic Environmental Assessment: A guide for practitioners. A report of Proecoserv, http://www.biofund.org.mz/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/1548141499-F2190.2014Guideline%20Es%20Into%20Sea-Unep-Proecoserv.Pdf [accessed on: 20.09.2021].

WAHRHUSEN, N. (2021), Governance einer flächensparenden Siedlungsentwicklung durch die Regionalplanung – Eine Analyse in städtisch und ländlich geprägten Regionen, Technische Universität Kaiserslautern. https://doi.org/10.26204/KLUEDO/6261

WILKINSON, C., SENDSTAD, M., PARNELL, S. and SCHEWENIUS, M. (2013), ‘Urban Governance of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services’, [in:] ELMQVIST, T., FRAGKIAS, M., GOODNESS, J., GÜNERALP, B., MARCOTULLIO, P. J., MCDONALD, R. I., PARNELL, S., SCHEWENIUS, M., SENDSTAD, M., SETO, K. C. and WILKINSON, K. (eds.). Urbanization, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Challenges and Opportunities, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 539–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7088-1_27

WIMES (2015), Integriertes Stadtentwicklungskonzept. 2. Fortschreibung. Bad Doberan, http://stadt-dbr.de/ISEK/ISEK2015/ISEK-Fortschreibung-2015.pdf [accessed on: 20.09.2021].

WIMES (2017), Bevölkerungsprognose für den Landkreis Rostock, https://www.landkreis-rostock.de/landkreis/daten_fakten/Bevxlkerungsprognose_2030_LK_Rostock.pdf [accessed on: 20.09.2021].

Received: 4.10.2021. Revised: 9.02.2022. Accepted: 9.03.2022.