A Decadal Systematic Review of Factors Underlying Tax Compliance in the Informal Sector

Simbarashe Show Mazongonda  *

*

Summary

Urban informality has been a subject of economic discussion for over five decades. Since the late 2000s, renewed interest has been focused on the sector’s rapid growth and frequent operation outside formal economic systems, raising pressing concerns about tax evasion and regulatory compliance. Previous attempts to tax the informal sector often fell short due to a failure to account for its heterogeneity, which distinguishes it from the formal sector. Effective tax collection in the informal sector hinges on operators’ compliance with the tax regime; however, discussions on the determinants of compliance in this context remain limited. This study addresses the need for an effective taxation framework for the informal sector by examining the role of tax compliance in this initiative. This study uses a systematic literature review of papers published between 2015 and 2024 and indexed in Scopus and Web of Science, to investigate the determinants of tax compliance within the informal economy. The findings indicate that compliance determinants can be categorized into governance quality, operational characteristics, tax morale, and the effectiveness of past and existing taxation strategies, with interconnected pathways linking these factors. This study advances the discourse on informal sector taxation in three key ways. First, it outlines tax compliance determinants within a structured framework, providing a basis for statistical analysis. Second, it offers practical insights for flexible, sector-specific taxation approaches. Third, it lays the groundwork for legislative discussions, potentially shaping standalone statutory instruments for formal and informal sectors. Considering the study’s limitations in scope and sampling bias, future research could explore variations within the informal sector through a taxation perspective, examine digital taxation strategies, and investigate the root causes of informality to gain a deeper understanding of their impact on contemporary tax compliance challenges.

Keywords: informal sector, taxation; tax compliance, operational characteristics, governance quality, tax morale, taxation strategy

Systematyczny przegląd czynników wpływających na przestrzeganie przepisów podatkowych w sektorze nieformalnym w latach 2015–2024

Streszczenie

Nieformalna działalność gospodarcza w miastach pozostaje przedmiotem zainteresowania ekonomistów od ponad pięćdziesięciu lat. Od końca pierwszej dekady XXI wieku rośnie zainteresowanie dynamicznym rozwojem tego sektora. Jego funkcjonowanie poza formalnymi strukturami gospodarczymi budzi obawy związane z unikaniem opodatkowania i nieprzestrzegania przepisów. Dotychczasowe próby opodatkowania sektora nieformalnego często kończyły się niepowodzeniem, głównie z powodu nieuwzględniania jego zróżnicowanej natury. Skuteczność poboru podatków w tym obszarze zależy od poziomu zgodności podatkowej jego uczestników, jednak kwestia ta pozostaje słabo zbadana.

Niniejsze badanie podejmuje próbę wypełnienia tej luki poprzez analizę czynników wpływających na przestrzeganie przepisów podatkowych w sektorze nieformalnym. W tym celu przeprowadzono systematyczny przegląd literatury z lat 2015–2024, obejmujący publikacje indeksowane w bazach Scopus i Web of Science. Wyniki wskazują, że determinanty zgodności podatkowej można podzielić na cztery główne kategorie: jakość rządzenia, cechy operacyjne, moralność podatkową oraz skuteczność dotychczasowych i obecnych strategii fiskalnych. Elementy te są wzajemnie powiązane i tworzą złożoną sieć zależności.

Badanie wnosi wkład w rozwój dyskusji na temat opodatkowania sektora nieformalnego na trzech poziomach: 1) proponuje uporządkowane ramy analizy zgodności podatkowej, 2) dostarcza praktycznych wskazówek dla elastycznego i dopasowanego podejścia do opodatkowania, 3) stanowi punkt wyjścia dla prac legislacyjnych nad odrębnymi regulacjami dla sektorów formalnego i nieformalnego. Mając na uwadze ograniczenia badania – w tym zakres tematyczny i możliwość błędu doboru próby – przyszłe analizy mogą skupić się na zróżnicowaniu wewnątrz sektora nieformalnego, strategiach opodatkowania cyfrowego oraz przyczynach powstawania nieformalności, by lepiej zrozumieć ich wpływ na wyzwania podatkowe współczesnych gospodarek.

Słowa kluczowe: sektor nieformalny, opodatkowanie, przestrzeganie przepisów podatkowych, charakterystyka działalności, jakość zarządzania, moralność podatkowa, strategia podatkowa.

Introduction

The concept of informality emerged in economic discussions during the 1970s when Hart (1973) examined informal employment and income in Ghana. At that time, scholars who advanced the idea of informality were influenced by a dualist perspective, which held that informality was a temporary phenomenon. This view assumed that informality would decline over time and with economic growth, as it was seen as merely a symptom of an underperforming economy (Despres, 1988; Ntlhola, 2010; Onoshchenko, 2012). Informality was perceived as a short-term solution to labor absorption, driven by rapid urbanization and economic crises, and thus little effort was directed toward its management.

A decade after its initial emergence, structuralist perspectives started challenging the assumption that informality would vanish over time. For instance, Granstrom (2009) and Bairagya (2010) used case data from Senegal and India, respectively, to demonstrate that the formal and informal sectors are interconnected, serving both complementary and competing roles (Narula, 2020). This indicates the existence of interconnections that contribute to the sector’s resilience and continuity, despite shifts in regulations and policy approaches. In the face of this recognition, attempts during this period to formalize and harness value from the informal sector often fell short, as authorities tended to apply the same management strategies to both formal and informal sectors. Additionally, research on urban informality has consistently highlighted that informal operators frequently free-ride, evade taxes, flout zoning regulations, and function with limited accountability due to their unique operational characteristics (Kanbur, 2010; Keen & Kanbur, 2015; Verberne & Arendsen, 2019).

The expansion of informal activities and the shortcomings of management strategies rooted in dualist and structuralist perspectives have reignited academic interest since the late 2000s and early 2010s (Varley, 2008). Contemporary studies (e.g., Yiftachel, 2009; Miraftab, 2009; Musara, 2015; Villamizar-Duarte, 2015), informed by post-colonial approaches to urban management, urban finance, and entrepreneurship, now recognize the resilience and inevitability of informality. These scholars highlight the sector’s heterogeneity, advocating for management and taxation strategies tailored to its distinct operational characteristics. This emerging body of work also draws on the Cost of Service Theory (CST), which argues that citizens should not expect free services and local public goods from the government, despite the state’s responsibility to finance and provide these goods. Instead of relying on formal direct taxation or intergovernmental grants, CST suggests that local revenue can be mobilized through informal taxation. Supporting this view, Olken & Singhal (2011) contended that informal taxation enables communities to address the free rider problem, thereby ensuring the provision of local public goods that might otherwise be underfunded. Specifically, Olken & Singhal (2011, p. 2) outlined that “informal taxation is a mechanism used to finance local public goods…a system coordinated by public officials but enforced socially rather than through the formal legal system”.

Olken & Singhal (2011) underscored the importance of designing taxation strategies tailored to the unique characteristics of the informal sector. This is particularly critical as many developing economies, particularly in Africa and Latin America, are increasingly dominated by informal activities, with significant financial resources circulating outside formal systems (Verberne & Arendsen, 2019; Dube & Casale, 2019; Maiti & Bhattacharyya, 2020; Chan, Dang, & Li, 2020; Isak & Mohamud, 2022; Bussy, 2023). While informality is a global phenomenon, its scale is notably larger in developing nations compared to their developed counterparts (Olga et al., 2015; Karlsson et al., 2020; Saifurrahman & Kassim, 2024). Over a decade ago, Schneider et al. (2010) reported that the informal sector constituted 38.4% of the economy in Africa, 36.5% in Europe and Central Asia (primarily transition countries), and 13.5% in high-income Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. Schneider et al. (2010) identified weak institutional and regulatory frameworks as the primary reason for higher informality in developing countries compared to developed ones. Under these conditions, informal enterprises flourish as entrepreneurs opt to operate outside the formal economy to bypass regulatory burdens.

Advocates of informal sector taxation argue that leveraging sector-specific tax frameworks could enhance revenue generation and sector management (Piccolino, 2015; Eriksson Baaz et al., 2018; Sebele-Mpofu, 2020; Anyidoho et al., 2023; Hammond et al., 2023; Akor et al., 2024). However, scholars such as Benhassine et al. (2018), Narula (2020), and Moore (2023) have highlighted concerns, noting that many informal operators engage in subsistence-level activities, face financial strain, and operate unsystematically. Additionally, Benhassine et al. (2018) argued that the cost of collecting taxes from this sector often outweighs potential revenues due to its typically small-scale operations. Despite these challenges, there is consensus on the need for informal sector participants to contribute to public services. Efforts are ongoing to develop efficient, equitable, and socially just taxation methods that minimize the burden on this sector while optimizing revenue generation. To successfully operationalize this initiative, Joshi et al. (2014, p. 1326) have suggested the “need for research into the conditions under which potential benefits are most likely to be realized”. One key condition identified is the need to understand the factors influencing tax compliance, given the inherently evasive nature of the informal sector (Keen & Kanbur, 2015). Busy (2023, p.) refers to this phenomenon as the “trade evasion channel”.

Taxing the informal sector has proven challenging due to low compliance rates among operators (Hammond et al., 2023). Tax compliance, defined as the willingness of operators to adhere to government tax requirements, is essential for a successful tax regime. However, compliance levels differ across regions and sectors, with the informal economy often deemed “hard-to-tax” due to its diverse and fluid nature (Verberne & Arendsen, 2019, p. 6; Aruoba, 2021). For example, the presumptive tax system has been criticized for its poor fit with the sector’s structure (Dube & Casale, 2019). Although there is growing advocacy for taxing the informal economy, understanding compliance is critical for designing effective taxation strategies. Few studies have thoroughly explored this issue, and the literature remains fragmented, evolving in multiple directions. This is reflected in the fact that only 28 papers published over the past decade were included in the review (see the methodology). Kanbur (2009, p.1) aptly described it as being “in a mess”, needing comprehensive and systematic packaging to inform policy and practice. Similarly, Sebele-Mpofu (2020) emphasized the need to foster voluntary compliance, particularly by systematically addressing financial issues within the informal sector.

This review addresses the question: what are the key drivers and barriers to tax compliance in the informal sector? This question is answered through a systematic review of studies published in the past decade (2015–2024) following the renewed interest in urban management and finance in the late 2000s and early 2010s. This study adopts the view that the informal economy, sector, or enterprise refers to economic activities that operate outside formal regulations but follow social norms within legally recognized informal domains (Bennihi et al., 2021; Routh, 2021). Economists often use ‘economy’ and ‘sector’ for broader commercial groupings, while business analysts use ‘enterprise’ to describe small business startups. The papers included in the review used these three terms, all referring to the same concept. Therefore, this paper employs all three terms interchangeably. The methodology, findings, and conclusions are discussed in subsequent sections.

Methodology and data

I conducted a systematic literature review to investigate the drivers and barriers to tax compliance among actors in the informal sector. Although there is no universally agreed-upon method for conducting such reviews, there is consensus that they must include well-defined research question(s), a replicable search strategy, clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, and a transparent process for transforming collected data into insights (Waddington et al., 2012; Krnic Martinic et al., 2019). The research protocol I adopted was shaped by the research question outlined earlier, the databases used for sourcing literature, language and timeframe restrictions, study type, and thematic focus. First, I purposively and conveniently selected Scopus and Web of Science (WS) as the primary search platforms. This choice was purposive to minimize bias by relying on more than one database and convenient because I had ready access to these resources during the study.

Second, my search was guided by two primary keywords, ‘informal sector’ AND ‘taxation’. Using these keywords, the search parameters were refined to include:

- Papers published in English between 2015 and 2024 inclusive, hence decadal review;

- Open-access publications; and

- Papers categorized under three subject areas: social studies, economics (econometrics and finance), and business (management and accounting).

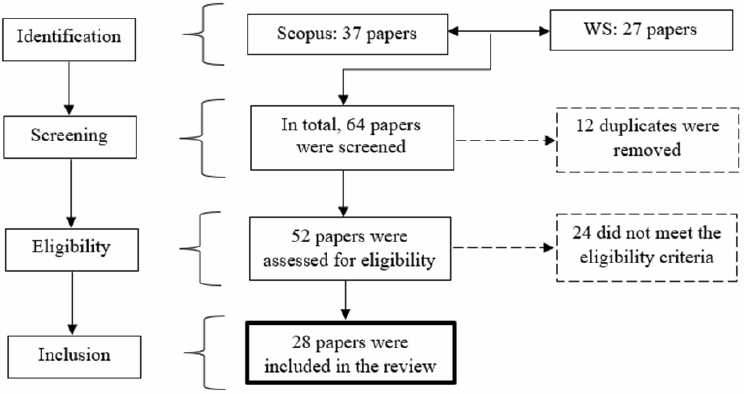

Third, the eligibility criteria were based on the relevance of a study’s objectives and contributions. The review included only papers that directly addressed tax compliance in the informal sector or indirectly explored the factors influencing and limiting compliance. Using this research protocol, I followed the four steps proposed by Waddington et al. (2012): identifying literature, screening identified papers, checking for eligibility of selected studies, and including studies in the final review. Figure 1 offers a visual overview of the results obtained after completing this four-step process.

Source: Own study (2024).

During identification, 64 papers were found: 27 from WS and 37 from Scopus. Then, 12 papers were dropped during screening because they were duplicates; that is, they appeared in both databases. So, 52 papers passed the screening stage, and I examined their abstracts for eligibility. 24 papers by Williams (2015), Araujo & Rodrigues (2016), Di Porto et al. (2017), Kuralbayeva (2018), Christiaensen & Martin (2018), Kuralbayeva (2019), Romanova et al. (2019), Lopez-Martin (2019), Nakabayashi (2019), Novikova et al. (2019), Bloeck et al. (2019), Narita (2020), Esaku (2021), Roy & Khan (2021), Williams & Krasniqi (2021), Langot et al. (2022), Mpofu & Mhlanga (2022), Doligalski & Rojas (2023), Arbex et al. (2023), Sahoo, Rout, & Jakovljevic (2023), Kalaitan et al. (2023), Keating (2024), Ho & Tirachini (2024), and McKay et al. (2024) did not meet the eligibility criteria. For example, their abstracts were not relevant to the research question, that is, they did not mention anything to do with tax compliance. Where taxation issues were raised, they were meant to clarify and specify certain issues, most of them not related to the core of this paper. So, a total of 28 papers were finally included in the decade-long review, constituting 54% of the papers with the keywords adopted for selection. Figure 2 provides a detailed summary of the included papers’ distribution across databases and years of publication.

Source: Own study (2024).

The year 2020 recorded the highest number of publications addressing the determinants of tax compliance in the informal sector, while 2017 did not contribute a single paper to the review. Regarding contributions from each database, Scopus yielded slightly more papers meeting the eligibility criteria compared to WS. During the screening process, 12 duplicate papers were identified, of which four met the eligibility criteria while the remaining eight did not. Figure 2 shows that Scopus did not have any publications meeting the eligibility criteria in 2016, evidenced by the absence of a bar for that year. Similarly, neither Scopus nor WS had eligible publications in 2017. In 2015 and 2019, both Scopus and WS contributed one publication each. Then, the line graph shows the total number of publications included in the review each year, irrespective of duplicates. Consequently, the analysis and discussion of findings in the subsequent sections are largely shaped by the composition of papers summarized and depicted in Figure 2.

Additionally, the review’s output is influenced by the types of included papers and the data and approaches they used. Of the 28 included papers, 26 are empirical papers, and two are conference proceedings, representing 93% and 7%, respectively. Regarding the data and approaches used, I classified the papers along two dimensions: primary versus secondary (or a combination of the two); and qualitative versus quantitative (or a mixture of the two). Table 2 presents the distribution of the reviewed papers based on these dimensions.

| no data | Absolute | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Dimension [ Primary versus Secondary ] | Primary | 14 | 50 |

| Secondary | 8 | 28.6 | |

| Combined | 6 | 21.4 | |

| Total | 28 | 100 | |

| Second Dimension [ Qualitative versus Quantitative ] | Qualitative | 11 | 39.3 |

| Quantitative | 12 | 42.9 | |

| Mixed-Methods | 5 | 17.9 | |

| Total | 28 | 100 | |

Source: Own study (2024).

Table 1 reveals that, for the first dimension, 50% of the eligible papers relied on primary data to explore the informality-taxation relationship, followed by 28.6% that used secondary data and 21.4% that employed a combination of both. The heavy reliance on primary data likely reflects the fact that this topic gained prominence in the late 2000s and early 2010s, limiting the availability of substantial secondary data tailored to this emerging area of study. This partially accounts for the limited number of accessible studies on the subject, particularly before 2018 (as highlighted in Figure 2). Arguably, this study represents one of the initial comprehensive reviews of the existing knowledge on this topic since its resurgence of interest over the past decade. Regarding the second dimension, there is a slight preference for quantitative approaches over qualitative ones, with only a marginal difference in their prevalence. Additionally, about 18% of the studies employed a mixed-methods approach, combining diverse perspectives to examine the factors driving tax compliance in the informal sector. Consistent with this paper’s objective of explaining the determinants of tax compliance in the informal sector, I used a manual textual analysis to review the 28 included papers. To ensure nuanced insights, I meticulously analyzed the texts, identifying underlying assumptions, contradictions, and recurring themes, with the findings presented in the next section.

Empirical results

In this section, results are thematically presented according to similarities and contradictions of ideas found in papers included in the review. Identified themes have been grouped into governance quality, operational characteristics, tax morale, and effectiveness of current strategies, with numerous pathways linking them. It must be noted that the identified themes are partly skewed and explained by the composition of reviewed papers.

Governance quality

Even though there are numerous stakeholders in a tax system, there are two key sides; the tax collector and the taxpayers’ sides. In this case, the taxpayers’ side is composed of informal operators and the tax collector is the government, mostly represented by appointed agencies or administrators. Considering these players, the performance of a tax system is largely dependent on the quality of the relationship between the taxpayer and the tax collector. Using the concept of fiscal sociology, Piccolino (2015) argued that effective taxation is based on a quasi-consensual relationship between the state and the taxpayers. It is this quasi-consensus that fuels tax compliance among economic players. This means, as Hammond et al. (2023) keenly observed, tax compliance is a function of the link between political trust and the quality of governments. It has been observed that administrators can easily win the trust of players in the informal sector if they uphold the principles of performance, professionalism, and impartiality (Piccolino, 2015; Hilson, 2020). Performance, as Anyidoho et al. (2023) noted, can be assessed according to the ability of the tax administrators to deliver their mandate as implied by the law, without deviating from what has been agreed upon or simply put, citizens’ attitude towards public services. Expanding on the issue of citizens’ attitudes, Verberne & Arendsen (2019) clarified that tax compliance attitudes are influenced by issues relating to taxpayers’ confidence and knowledge of the tax regime. But, where do taxpayers get some of this knowledge? Ansong (2024) gave some proxies to this question by noting that administrators best execute their duties, including educating taxpayers when they serve and act professionally. In any given country, tax systems are run on set institutional rules and administrative procedures, and adherence to these rules of engagement brings about confidence in the government. So, if administrators exhibit higher levels of performance and professionalism, the greater the trust citizens have in them, and the greater the chance of preventing financial cheating and tax evasion. Professionalism, according to Sebele-Mpofu (2020), can be viewed through the lens of the impartiality of tax administrators. It has been asserted that enforcement must be combined with tax reforms that improve transparency and accountability in the use of tax revenues to boost tax morale and heighten tax compliance in developing countries (Akpan, 2022; Saifurrahman & Kassim, 2024).

Scholars such as Dube & Casale (2019) and Bertinelli et al. (2020) used case data from Zimbabwe and Mali, respectively, to show how impartiality is compromised on the count of politics. For example, Dube & Casale (2019) characterized deregulation as a selective, and sometimes politically motivated, application of law. This brings about an uneven playing field because some taxpayers are exempted from certain sections of the law whilst some are caught on the wrong side of the law using the same sections. Bertinelli et al. (2020) clarified that the selective application of law undermines both vertical and horizontal equity. On one hand, horizontal equity refers to the uniform application of law to economic players in the same tax bracket regardless of who they are affiliated with. On the other hand, vertical equity defines fairness that applies to economic players in different tax brackets. For example, taxpayers in a lower tax bracket are charged a percentage that is lower than players in a higher tax bracket. The idea is to ensure that those who earn more, pay more, and those who earn less, pay less. According to Bertinelli et al. (2020), horizontal and vertical inequity, as an act of corruption, takes the form of misuse of resources or power for private gain. Similarly, Ansong (2024) has argued that taking bribes by administrators significantly reduces tax compliance.

Moore (2023) outlined the political dimension of taxation that diverts people’s attention by showing how the continual drive to register more taxpayers provides an impression of the tax administrators’ efforts to collect more revenue. In such a narrative, the general populace is made to believe that under taxation of small enterprises, mostly in the informal sector, is the main explanatory factor for revenue scarcity. Moore (2023) underlined that this helps divert attention from corrupt tendencies involving tax administrators and larger enterprises. To this effect, Maiti & Bhattacharyya (2020) have described weak enforcement in the informal sector as deliberate. For example, the state can heavily tax the formal sector to subsidize informal income and finance public infrastructure. It has, therefore, been reasoned that deregulation and weak enforcement are sites of considerable state power where politicians (through their administrators) retain electoral loyalty from people exercising informality. So, tax systems are, arguably, designed to paint a certain narrative that serves the interests of vote-seeking politicians, thereby compromising the quality of governance. But how does the quality of governance shape, or is shaped by the operational characteristics of the informal sector?

Operational characteristics

Several sources have shown that the quality of governance has some causal linkages with the way the informal sector operates (Bertinelli et al., 2020; Maiti & Bhattacharyya, 2020; Isak & Mohamud, 2022; Bussy, 2023; Moore, 2023). Major explanatory variables to informal sector operations are deeply rooted in urban management, politics, and tax policies. In an attempt to explain issues around tax compliance in Somalia, Isak & Mohamud (2022) noted that the country has been experiencing civil unrest since 1991. This resulted in social, economic, and political instability, and the destruction of governance systems, including the taxation culture. So, informality is located in an operating environment characterized by limited administrative capacity and the high costs involved in enforcing compliance, all hindering the proper management of the taxation system. Furthermore, economic instability resulting from civil unrest challenges the smooth management of administrative systems. This challenge is not peculiar to Somalia, but African countries such as Cameroon, Burundi, Chad, Niger, Somalia, Ethiopia, Mali, and Mozambique recorded intra-state conflicts in 2019 alone. During conflicts, some economic players take advantage of the chaos to evade taxes.

Bussy (2023) introduced a new dimension to understanding informal sector operations by highlighting the ‘trade evasion channel’. Through this channel, some firms manipulate their reported imports and exports to understate taxable profits and evade Corporate Income Taxes (CIT). This is facilitated by poor record-keeping and the lack of professional audits, as informal businesses often operate outside formal regulatory frameworks. The sector’s fluidity and intense competition further complicate accurate bookkeeping, as price negotiations are common (Dube & Casale, 2019). Consequently, formal businesses often subcontract to the informal sector, allowing tax authorities to focus on formal enterprises while tax evasion thrives unnoticed. This channel suggests that the formal sector appears to be producing a paltry output while goings-on in the informal sector are not closely monitored, yet a significant percentage of the economic activity will be taking place in the often unnoticed, ‘organism-like’ informal sector.

Apart from the deliberate tricks used by informal operators to evade tax channels, their operations are difficult to tax because they are disorderly. In light of this challenge, Verberne & Arendsen (2019) labelled the informal sector as ‘hard-to-tax’ considering its operational characteristics (that is, its nature, size, composition, and location). For example, Moore (2023) noted that most informal sector operations are characterized by players who are using survivalist strategies to eke a living and are, in some cases, ignorant of taxation issues. Some of these players operate in their backyards not known to tax administrators. So, taxing this sector is a mammoth task amid these challenges that make it difficult to systemize their operations. Where the operations are somewhat orderly, players’ psychographics (that is, their attitude, knowledge, and perception) toward tax compliance must be improved (Eriksson Baaz et al., 2018; Hilson, 2020; Hilson et al., 2023). The next sub-section discusses the quality of human factors and their inherent influence on the intention to comply.

Tax morale and the intention to comply

Sebele-Mpofu (2020) described tax morale as the intrinsic motivation of informal operators to pay taxes, reflecting an internal sense of confidence or discipline to act in a certain manner. This suggests that tax morale is influenced by behavioral, normative, and control beliefs or assumptions. Behavioral beliefs pertain to the perceived costs and benefits of acting in a particular way. Similarly, Rahou & Taqi (2021) framed this concept as a cost-benefit analysis regarding the use of tax revenues. For instance, when operators perceive that the benefits of paying taxes outweigh the costs, they are more likely to adopt a positive attitude toward contributing to public funds. Hilson’s (2020) position supports this perspective, concluding that both tax collectors and taxpayers are often inclined toward mutually beneficial arrangements. Many informal operators, recognizing the advantages of working within a structured and regulated system, are eager to participate in such frameworks. Thus, attitude plays a critical role in tax compliance, reflecting an individual’s evaluation of the process. The stronger the belief that compliance will yield greater benefits, the stronger the intention to comply, and vice versa.

Behavioral beliefs are influenced by social pressure and control beliefs. Informal operators often share ideas, experiences, knowledge, tools, and skills within their operational environments (Sebele-Mpofu, 2020). This interaction creates direct or indirect pressure among peers regarding tax compliance. An individual’s intention to pay taxes is shaped by the general social pressure exerted by other operators, who influence the approval or disapproval of such actions. Eriksson Baaz et al. (2018) and Hammond et al. (2023) similarly argued that this pressure arises through shared knowledge as operators interact and network daily in their workplaces. Informal sector players often regulate one another, fostering solidarity under the principle of ‘injure one, injure all’, a trait that differentiates them from formal sector operators. Furthermore, Sebele-Mpofu (2020) highlighted that informal operators also share beliefs about how tax revenue is used by the government for public goods and services in their areas of operation. These shared perspectives often lead to unified attitudes, where individuals’ intentions to comply are influenced by perceived social pressure. Collectively, informal sector participants evaluate the fairness of the tax system and their capacity to pay, considering the benefits they expect from compliance (Hilson, 2020; Verberne & Arendsen, 2019).

Despite the general social pressure exerted by peers, individual economic players are influenced by their own perceived constraints on the intention to comply. Differences in backgrounds among economic players lead to variations in their compliance intentions (Sebele-Mpofu, 2020). For instance, some individuals possess greater tax knowledge due to higher levels of education, while others benefit from political connections. These variations reflect control beliefs, which pertain to the perceived influence of internal and external factors in facilitating or hindering tax compliance. Verberne & Arendsen (2019) illustrated this through the differing perceptions of authorities’ enforcement power, often influenced by an individual’s connections with enforcement officers. Similarly, Akpan et al. (2022) discussed how the tax system and tax collectors exhibit gender bias, highlighting how differences in gender, social standing, and political affiliation shape individuals’ tax morale and intention to comply. These internalized control beliefs play a critical role in shaping compliance behavior.

Knowledge of past and current taxation strategies

Countries with high levels of informality have made numerous attempts to tax the informal sector, but many of these efforts have fallen short of expectations (see Charlot et al., 2016; Eriksson Baaz et al., 2018; Dube & Casale, 2019; Bertinelli et al., 2020; Chan et al., 2020; Schipper, 2020; Elgin et al., 2022; Anyidoho et al., 2023; Akor et al., 2024). Evidence suggests that the poor performance of these strategies often stems from their lack of alignment with the diverse and heterogeneous nature of the informal sector (Verberne & Arendsen, 2019; Aruoba, 2021). For instance, Dube & Casale (2019) highlighted that the Zimbabwean government introduced a presumptive tax for the informal sector in 2005, relying solely on a survey of informal public transport operators. It was incorrectly assumed that this approach would be effective across all informal sector variants. To broaden the tax base, additional variants of informality were added to the tax schedule without empirical justification. This initiative saw limited success, as presumptive tax relies on estimated indicators rather than measurable bases. Applying assumptions from the informal transport sector to other variants proved to be a significant miscalculation, leading to implementation challenges.

Another example of an ineffective taxation strategy in the informal sector is CIT, analyzed by Bussy (2023) using the ‘trade evasion channel’. As previously mentioned, CIT functions optimally under ideal conditions, where accurate record-keeping and honest reporting of economic activities are upheld. However, achieving this in the informal sector is highly challenging due to its unique operational dynamics and the poor governance quality outlined earlier. These factors make it difficult to enforce CIT effectively, further complicating efforts to integrate the informal sector into the formal tax system.

This underscores the need for taxation strategies specifically tailored to the informal sector, informed by lessons from past and current approaches. Hammond et al. (2023) sought to understand the reasons behind the poor performance of previous taxation strategies targeting the informal sector. They identified perceptions of tax administration as the most significant barrier to the success of tax policies. Repeated unsuccessful attempts to tax the informal sector may have eroded trust in tax administrators, contributing to low tax morale among informal sector operators. This lack of trust and low morale likely hinders compliance. Thus, an in-depth examination of past taxation strategies, particularly in terms of compliance outcomes, is crucial for developing more effective approaches tailored to the unique dynamics of the informal sector.

Discussion and conclusion

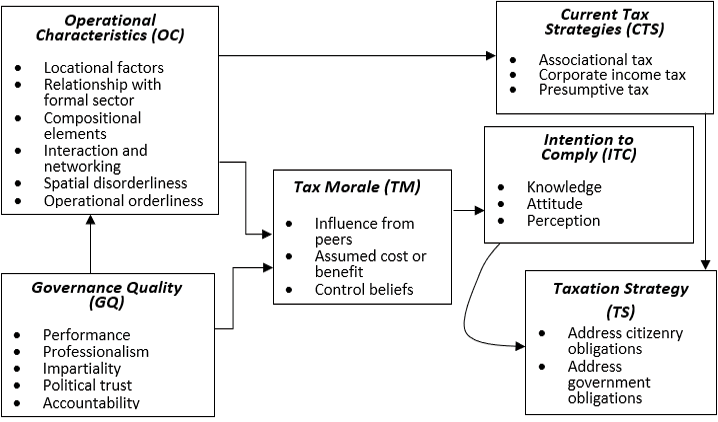

Since determinants of tax compliance in the informal sector have numerous explanatory factors, some emanating from the taxpayers’ side and some from the tax collector’s side, there is a need for a halfway-through approach, incorporating the expectations of both parties in designing a workable taxation strategy. Most traditional approaches to taxation have failed on the count of compliance because they are top-down driven, with limited room to incorporate the taxpayers’ views. Against this background, Meagher (2018) and Verberne & Arendsen (2019) have argued that gaining a bottom-up understanding of taxation in the informal sector and improving tax morale is key to designing an effective taxation strategy. This review has revealed that the key variables driving and restraining tax compliance by players in the informal sector include their operational characteristics, governance quality, tax morale, and current tax strategies, and how they culminate into an all-inclusive taxation strategy. Figure 3 shows the interdependence of these factors.

Source: Own study (2024).

Sebele-Mpofu’s (2020) study on the determinants of taxation strategy highlighted the intrinsic connection between governance quality, tax morale, and tax compliance. The research noted that tax morale impacts tax compliance, while governance quality, in turn, affects tax morale. Such scholarly work is valuable, as it offers insights into the relationship between urban informality and tax compliance. Sebele-Mpofu’s contribution is crucial for developing a well-rounded understanding of the factors influencing tax compliance. However, questions remain about the comprehensiveness of her analysis.

Firstly, her study did not explore how the unique operational characteristics of the informal sector influence tax morale. For example, Verberne & Arendsen (2019, p.6) characterized the informal sector as “hard-to-tax” due to its distinct features, such as its nature, size, and location. This suggests that the way informal operators interact and network in their daily activities could partially shape their intentions to comply with tax obligations. Secondly, the study did not assess the effectiveness of past and existing taxation strategies. Studies by Dube & Casale (2019), Verberne & Arendsen (2019), and Bussy (2023) have shown that past and current taxation strategies have struggled to effectively levy the informal sector. In light of this, Isak & Mohamud (2022) emphasized the need to align the growth of the informal economy with taxation efforts, advocating for building society’s capacity to pay taxes rather than solely focusing on the state’s ability to enforce tax collection. In response, the present study incorporates these two dimensions, operational characteristics, and current tax strategies, into Sebele-Mpofu’s conceptual model, refining and mapping multiple pathways that link these factors, thus creating a socially binding framework that comprehensively captures all the determinants.

The preceding paragraphs explored the determinants of tax compliance in the informal sector through a systematic review of 28 papers published between 2015 and 2024, sourced from Scopus and WS databases. This review was driven by the recognition that few studies have thoroughly investigated this issue, despite tax compliance being a critical factor in the success of taxation strategies within the informal economy. This approach is grounded in post-colonial perspectives on informality and the CST, which views informality as a quasi-permanent phenomenon that, while distinct in its operational characteristics, must still contribute to public revenue. The analysis identified key factors shaping taxation strategy and the intention to comply, including governance quality, operational characteristics, tax morale, and the structure of previous and current taxation strategies. Figure 3 illustrates the various pathways linking these factors, providing a framework for statistically analyzing their interaction.

Although there is a negligible difference between the number of studies that qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed these relationships (see Table 2), Moore (2023) highlighted the lack of statistical data on the functioning of national tax administrations in economies with high informality. While quantitative analyses are limited and often not comprehensive, the financial issues within the informal economy, by their very nature, require quantitative examination to inform policy. To address this gap, this study systematically explored the factors underlying tax compliance in the informal sector and organized them into a conceptual model to facilitate statistical analysis. This thorough approach provides a robust foundation for evaluating the performance of the conceptual model.

This study’s key contribution to the literature on financial issues in the informal economy is its development of a conceptual model for tax compliance, synthesized from studies conducted over the past decade. The model integrates a measurement framework of six factors (OC, GQ, TM, CTS, ITC, and TS) with a structural path illustrating their interrelationships. Unlike previous fragmented studies, which have limited cohesive insights into policy and practice, this model provides a comprehensive approach to understanding tax compliance in the informal sector. Additionally, it extends the conventional CST, which does not clarify how formal and informal economic players must contextually contribute to the fiscus, by proposing a viable taxation framework for the so-called ‘hard-to-tax’ sector (Verberne & Arendsen, 2019). As such, this study underscores the contextual nature of tax compliance and introduces the missing dimension of informality to taxation theory and practice.

From a practical perspective, the present study clarifies the determinants of tax compliance in the informal sector. Historically, taxation strategies for the informal economy have been modeled after formal sector frameworks, overlooking key operational differences. This study highlights tax evasion tactics unique to the informal sector, such as the ‘trade evasion channel’ reported by Busy (2023). By identifying these tactics, the study advocates for tailor-made and flexible taxation approaches that could improve compliance. Furthermore, given that tax policies are heavily regulated at both central and local government levels, this study has significant policy implications. Its findings offer a foundation for legislative debates on tax compliance determinants, potentially informing the development of standalone statutes or statutory instruments specific to formal and informal sectors. These policy insights contribute to more equitable and effective tax regulations, improving both compliance and overall tax system performance.

Future research can build on this study’s conceptual model by quantitatively assessing the measurement framework for the six factors using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Essentially, CFA ensures the reliability and validity of these factors by evaluating their respective indicators, as illustrated in Figure 3. For instance, governance quality can be assessed through indicators such as performance, professionalism, impartiality, political trust, and accountability. Additionally, the structural framework can be assessed by examining the statistical significance of relationships between latent variables (sex factors) and the predictive strength of the conceptual model.

A key gap identified in this study is the lack of research on the potential of digital tools to enhance taxation transparency and efficiency, with 28 reviewed papers not addressing this aspect. Future studies could explore financial inclusion and digital taxation within the informal sector, potentially offering sustainable and practical insights to improve tax policy and practice. Furthermore, beyond distinguishing the informal sector from the formal sector, there are variations within the informal sector that remain unexplored in this study. For example, its variations across primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of production. Future research could delve into these differences to provide context-specific policy recommendations tailored to the operational characteristics of each segment.

This study is also limited by its focus on literature from the past decade, which primarily addresses the symptoms of informality. Instead of narrowly focusing on these symptomatic issues, future research can investigate the root causes of informality. Addressing these underlying factors could lead to more effective and long-term solutions, ultimately reducing the persistence of informal economic activities. For example, this study briefly touched on corruption in tax administration but does not deeply explore the broader political economy of taxation, including elite capture and institutionalized corruption. Given that issues of governance and corruption are deeply embedded in institutional change processes, future studies can examine these dynamics at a systemic level. Such research could help create a foundation for implementing the recommendations of this study. Overall, this study provides a comprehensive review of tax compliance in the informal sector while setting a clear research agenda synthesized from a decadal (decade-long) systematic review.

Author

References

Akor I.C., Ogeze Ukeje I., Ezirim G.E., Iwuoha V., Ibeh C.E. & Kanu C., 2024, State taxation of the motorcycle transport business and internally generated revenue in Ebonyi State, Nigeria, 2015 to 2021, SAGE Open, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241243255

Akpan I. & Cascant-Sempere M.J., 2022, Do tax policies discriminate against female traders? A gender framework to study informal marketplaces in Nigeria, ‟Poverty and Public Policy”, 14(3), pp. 287–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/pop4.349

Ansong J.D., Asamoah M.K., Agyekum B. & Nketiah-Amponsah E., 2024, The influence of education on addressing the challenges of taxation and cocoa revenue mobilization in Ghana, “Social Sciences & Humanities Open”, Vol. 10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2024.101098

Anyidoho N.A., Gallien M., Rogan M. & van den Boogaard V., 2023, Mobile money taxation and informal workers: Evidence from Ghana’s e-levy, “Development Policy Review”, 41(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12704

Araujo J.P. & Rodrigues M., 2016, Taxation, credit constraints and the informal economy, “EconomiA”, 17(1), pp. 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econ.2016.03.003

Arbex M., Correa M.V. & Magalhaes M.R.V., 2023, Tolerance of informality and occupational choices in a large informal sector economy, “The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics”, 23(1), pp. 241–278. https://doi.org/10.1515/bejm-2021-0076

Aruoba S.B., 2021, Institutions, tax evasion, and optimal policy, “Journal of Monetary Economics”, Vol. 118, pp. 212–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2020.10.003

Bairagya I., 2010, Liberalization, informal sector, and formal-informal sectors’ relationship: A study of India. Unpublished DPhil Thesis, Institute for Social and Economic Change: India.

Benhassine L. & Martin W., 2018, Agriculture, structural transformation and poverty reduction: Eight new insights, “World Development”, Vol. 109, pp. 413–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.027

Benhassine N., McKenzie D., Pouliquen V. & Santini M., 2018, Does inducing informal firms to formalize make sense? Experimental evidence from Benin, “Journal of Public Economics”, Vol. 167, pp. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.11.004

Bennihi A.S., Bouriche L. & Schneider F., 2021, The informal economy in Algeria: New insights using the MIMIC approach and the interaction with the formal economy, “Economic Analysis and Policy”, Vol. 72, pp. 470–491.

Bertinelli L., Bourgain A. & Léon F., 2020, Corruption and tax compliance: evidence from small retailers in Bamako, Mali, “Applied Economics Letters”, 27(5), pp. 366–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2019.1616057

Bloeck M.C., Galiani S. & Weinschelbaum F., 2019, Poverty alleviation strategies under informality: Evidence for Latin America, “Latin American Economic Review”, 28(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s40503-019-0074-4

Bussy A., 2023, Corporate tax evasion: Evidence from international trade, “European Economic Review”, Vol. 159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2023.104571

Chan K.S., Dang V.Q.T. & Li T.T., 2020, Corruption and income inequality in China, “Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 56(14), pp. 3351–3366. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2019.1675632

Charlot O., Malherbet F. & Ulus M., 2016, Unemployment compensation and the allocation of labor in developing countries, “Journal of Public Economic Theory”, 18(3), pp. 385–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpet.12144

Despres L.A., 1988, Macrotheories, microcontexts, and the informal sector: Case studies of self-employment in three Brazilian cities, Working Paper Number 110, Kellogg Institute.

Di Porto E., Elia L. & Tealdi C., 2017, Informal work in a flexible labour market, “Oxford Economic Papers”, 69(1), pp. 143–164. DOI: 10.1093/oep/gpw010

Doligalski, P., & Rojas, L.E. (2023). Optimal redistribution with a shadow economy. Theoretical Economics, 18(2), 749–791. https://doi.org/10.3982/TE4569

Dube G. & Casale D., 2019, Informal sector taxes and equity: Evidence from presumptive taxation in Zimbabwe, “Development Policy Review” 37(1), pp. 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12316

Elgin C., Torul O. & Turk T., 2022, Marginal cost of public funds under the presence of informality, “Hacienda Publica Espanola”, 241(2), pp. 79–103. https://doi.org/10.7866/HPE-RPE.22.2.4

Eriksson Baaz M., Olsson O. & Verweijen J., 2018, Navigating ‘taxation’ on the Congo River: the interplay of legitimation and ‘officialisation’, “Review of African Political Economy”, 45(156), pp. 250–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2018.1451317

Esaku S., 2021, Does income inequality increase the shadow economy? Empirical evidence from Uganda, “Development Studies Research”, 8(1), pp. 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/21665095.2021.1939082

Granstrom S.C., 2009, The Informal Sector and Formal Competitiveness in Senegal, Minor Field Study Series, University of Lund.

Hammond P., Kwakwa P.A., Berko D. & Amissah E., 2023, Taxing informal sector through modified taxation: Implementation challenges and overcoming strategies, “Cogent Business and Management”, 10(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2274172

Hart K., 1973, Informal Income Opportunities and Urban Employment in Ghana,“Modern African Studies”, 11(1), pp. 61–89.

Hilson G., 2020, The ‘Zambia Model’: A blueprint for formalizing artisanal and small-scale mining in sub-Saharan Africa?, “Resources Policy”, Vol. 68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101765

Ho C.Q. & Tirachini A., 2024, Mobility-as-a-service and the role of multimodality in the sustainability of urban mobility in developing and developed countries, “Transport Policy”, Vol. 145, pp. 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2023.10.013

Isak N.N. & Mohamud A.A., 2022, Managing the taxation of the informal business sector in Mogadishu, “Journal of Tax Administration”, 7(1), pp. 96–115.

Joshi A., Prichard W. & Heady C., 2014, Taxing the informal economy: The current state of knowledge and agendas for future research, “The Journal of Development Studies”, 50(10), pp. 1325–1347.

Kalaitan T., Hrymak O., Kushnir L., Kondrat I. & Yaroshevych N., 2023, Shadow economy in the hospitality industry: Ways of it’s reduce in Ukraine, “Financial and Credit Activity: Problems of Theory and Practice”, 2(49), pp. 300–312. https://doi.org/10.55643/fcaptp.2.49.2023.4002

Kanbur R., 2009, Conceptualising informality: Regulation and enforcement, “Indian Journal of Labour Economics”, 52(1), pp. 33–42.

Karlsson I.C.M., Mukhtar-Landgren D., Smith G., Koglin T., Kronsell A., Lund E., Sarasini, S. & Sochor J., 2020, Development and implementation of mobility-as-a-service: A qualitative study of barriers and enabling factors, “Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice”, Vol. 131, pp. 283–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2019.09.028

Keating P., 2024, The ideological dilemma in using games in global citizenship and development education, “Proceedings of the European Conference on Games-based Learning”, 18(1), pp. 499–505. https://doi.org/10.34190/ecgbl.18.1.2721

Keen M. & Kanbur R., 2015, Reducing informality, “Finance and Development”, 52(1), pp. 52–54.

Krnic Martinic M., Azaiza F., Jovanović D. & Čolić D., 2019, Definition of a systematic review used in overviews of systematic reviews, meta-epidemiological studies, and textbooks, “BMC Medical Research Methodology”, 19(1), p. 140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0855-0

Kuralbayeva K., 2018, Unemployment, rural–urban migration, and environmental regulation, “Review of Development Economics”, 22(2), pp. 507–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12360

Kuralbayeva K., 2019, Environmental taxation, employment, and public spending in developing countries, “Environmental and Resource Economics”, 72(4), pp. 877–912. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-018-0230-3

Langot F., Merola R. & Oh S., 2022, Can taxes help ensure a fair globalization?, “International Economics”, Vol. 171, pp. 191–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2022.06.003

Lopez-Martin B., 2019, Informal sector misallocation, “Macroeconomic Dynamics”, 23(8), pp. 3065–3098. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1365100517001055

Maiti D. & Bhattacharyya C., 2020, Informality, enforcement, and growth, “Economic Modelling”, Vol. 84, pp. 259–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2019.04.015

Maiti K., 2018, Taxing times: Taxation, divided societies, and the informal economy in Northern Nigeria, “Journal of Development Studies”, 54(1), pp. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2016.1262026

McKay A., Pirttilä J. & Schimanski C., 2024, The tax elasticity of formal work in Sub-Saharan African countries, “Journal of Development Studies”, 60(2), pp. 217–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2023.2279477

Miraftab F., 2009, Insurgent Planning: Situating Radical Planning in the Global South, “Planning Theory”, 8(1), pp. 32–50.

Moore M., 2023, Tax obsessions: Taxpayer registration and the informal sector in sub-Saharan Africa, “Development Policy Review”, 41(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12649

Mpofu F.Y. & Mhlanga D., 2022, Digital financial inclusion, digital financial services tax, and financial inclusion in the fourth industrial revolution era in Africa, “Economies”, 10(8), https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10080184

Musara M., 2015, Entrepreneurial ideology: A discourse so paradoxical, “Africa Growth Agenda”, 12(1), pp. 16–19.

Nakabayashi M., 2019, From family security to the welfare state: Path dependency of social security on the difference in legal origins, “Economic Modelling”, 82, pp. 280–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2019.01.011

Narita R., 2020, Self-employment in developing countries: A search-equilibrium approach, “Review of Economic Dynamics”, Vol. 35, pp. 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2019.04.001

Narula R., 2020, Policy opportunities and challenges from the COVID-19 pandemic for economies with large informal sectors, “Journal of International Business Policy”, 3(3), pp. 302–310. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-020-00059-5

Novikova O., Ostafiichuk Y. & Khandii O., 2019, Social justice and economic efficiency of the modern labour market, “Baltic Journal of Economic Studies”, 5(3), pp. 145–151. https://doi.org/10.30525/2256-0742/2019-5-3-145-151

Ntlhola M.A., 2010, Estimating the relationship between informal sector employment and formal sector employment in selected African countries, Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Finance University of KwaZulu-Natal: South Africa.

Olga K., Eldar S., Ruslan F. & Anastasiya K., 2015, Assessment of influence of the labor shadow sector on the economic growth of the Russian economy with the using methods of statistical modeling, “Procedia Economics and Finance”, Vol. 23, pp. 180–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00525-0

Olken B.A. & Singhal M., 2011, Informal taxation, “American Economic Journal: Applied Economics”, Vol. 3, pp. 1–28.

Onoshchenko O., 2012, Tackling the Informal Economy in Ukraine. Unpublished DPhil Thesis, University of Sheffield: United Kingdom.

Piccolino G., 2015, Does democratisation foster effective taxation? Evidence from Benin, “Journal of Modern African Studies”, 53(4), pp. 557–581. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X15000750

Rahou E.H. & Taqi A., 2021, Informal micro-enterprises: What impact does the business environment have on the decision of formalization?, “E3S Web of Conferences”, Vol. 234. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202123400052

Romanova A.S., Kovalchuk V.B., Savenko V.V., Yevkhutych I.M. & Podra O.P., 2019, Economic and legal aspects of human capital investments providing in Ukraine, “Financial and Credit Activity-Problems of Theory and Practice”, 3(30), pp. 490–500. https://doi.org/10.18371/fcaptp.v3i30.179925

Routh S., 2021, Examining the legal legitimacy of informal economic activities, “Social and Legal Studies”, XX(X): 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/09646639211020817

Roy P. & Khan M.H., 2021, Digitizing taxation and premature formalization in developing countries, “Development and Change”, 52(4), pp. 855–877. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12662

Sahoo P.M., Rout H.S. & Jakovljevic M., 2023, Consequences of India’s population aging to its healthcare financing and provision, “Journal of Medical Economics”, 26(1), pp. 308–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2023.2178164

Saifurrahman A. & Kassim S.H., 2024, Regulatory issues inhibiting the financial inclusion: a case study among Islamic banks and MSMEs in Indonesia, “Qualitative Research in Financial Markets”, 16(4), pp. 589–617. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRFM-05-2022-0086

Schneider F., Buehn A. & Montenegro C.E., 2010, Shadow Economies all over the World: New Estimates for 162 Countries from 1999 to 2007, Policy Research working paper 5356. The World Bank Development Research Group Poverty and Inequality Team, & Europe and Central Asia Region Human Development Economics Unit.

Sebele-Mpofu F.Y., 2020, Governance quality and tax morale and compliance in Zimbabwe’s informal sector, “Cogent Business and Management”, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1794662

Varley A., 2008, Postcolonialising Informality? Paper given from Villas Miseria to Colonias Populares: Latin America’s Informal Cities in Comparative Perspectives. Northwestern University Program on Latin America and Caribbean Studies, Evanston, IL, 13 June.

Verberne J. & Arendsen R., 2019, Taxation and the informal business sector in Uganda: An exploratory socio-legal study, “Journal of Tax Administration”, 5(2), pp. 6–25.

Villamizar Duarte N., 2015, Informalization as a Process: Theorizing Informality as a Lens to Rethink Planning Theory and Practice in Bogota, Colombia, Extended abstract presented at RC21 Conference 2015 The Ideal City: Between Myth and Reality, http://www.rc21.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Vllamizar-Duarte-_-RC21-2015-_-Extended-Abstract-12.10.2016.pdf

Waddington H., White H., Snilstveit B., Hombrados J.G., Vojtkova M., Davies P., Tugwell P., 2012, How to do a good systematic review of effects in international development: a tool kit, “Journal of Development Effectiveness”, 4(3), pp. 359–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2012.711765

Williams C. & Krasniqi B., 2021, Beyond the formal/informal employment dualism: evaluating individual- and country-level variations in the commonality of quasi-formal employment, “International Journal of Social Economics”, 48(9), pp. 1290–1308. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-01-2021-0059

Williams, C.C. (2015). Out of the shadows: Classifying economies by the extent and nature of employment in the informal economy. International Labour Review, 154(3), 331–351. DOI: 10.1111/j.1564-913X.2015.00245.x

Yiftachel O., 2009, Theoretical Notes on ‘Gray Cities’: The Coming of Urban Apartheid, “Planning Theory”, 8(1), pp. 87–99.