https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3310-387X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3310-387X

Bridging the gap between housing supply and needs is based on the fact that this is not possible with the government support alone as private investors are also crucial here. However, new opportunities have arisen for companies for which residential offerings in city centers are essential to their operations. For several years now, commerce has invested in real estate not only to build retail branches, but also in conjunction with housing. German cities are very interested in this type of projects, where valuable space in city centers above existing single-story stores is used for housing. As of 2018, some retail chains have combined their downtown sales interests with residential interests in the city. The research question posed in this paper is whether private investments could increase the availability of social and affordable housing.

Keywords: social housing, German housing policy, densification, private investors, sustainability

JEL: R21, R28, R32

Although Germany has a long tradition of social housing, it is widely recognized that the history of modern social housing began about a century ago. The situation has changed over time. There have been natural fluctuations, including periods of peak demand for housing programs, especially after the two world wars. More than a decade ago, some housing programs came to an end for a variety of reasons such as e.g. a changing population structure. Evolving demographics showed a declining demand for housing in general – to name just two of many other reasons. Since the fixed guaranteed rent in the government programs has exhausted itself over the years, and almost no new housing projects have been developed, the social housing market has almost disappeared. The social housing model with its features has also become less interesting to investors.

As in the case of urban development, the provision of housing is also a political task in Germany. Traditionally, resource development and housing have been the main tasks of German urban renewal. However, a look at the beginning of the new century shows that the situation is different.

In 2006, Germany introduced federal reforms. At that time, housing lost its political importance, as evidenced by the federal government’s withdrawal from this task. Responsibility for it was transferred to the state level (Schmitt 2017). This development is described as leaving housing to the markets in a framework that involves the government side as little as possible, a consequence of neoliberalism (Ringwald 2020). Since the policy changes, there has been an unprecedented development, while the demand for housing and the gap between available and needed housing have continued to grow. These factors, as well as the fact that the market has focused on high-quality, more expensive housing, have resulted in higher housing prices. The greatest impact of these changes is seen in social and affordable housing. While the fixed guaranteed rent in the government programs has run out, many tenants have remained in them even when they no longer met the conditions for a housing voucher, as they did when they moved in; meanwhile, fewer new apartments have begun to be built (Koch 2017; Ringwald 2020).

However, the situation changed in 2018. Employment opportunity companies emerged mainly in urban areas, there was an increase in the number of single-person households and, most importantly, an unforeseen significant influx of migrants. This has had a profound effect on the housing market, increasing the demand for affordable social housing and further exacerbating Germany’s already tight housing situation. Most migrants initially receive temporary housing, yet, over time they need a living space, which is theoretically easiest to provide in the social housing sector. However, this situation can lead to “competition between migrants and other groups in social need” (Gliemann 2018).

As of 2018, some retail chains combined their commercial interests in the urban center with their residential interests in the city while fitting their actions into the concept of densification.

This could be a win-win situation for German cities, retail stores and residents looking for residential spaces. Retail store chains are planning to build residential units on top of existing single-story buildings, or to build new retail spaces combined with residential units. The potential for such re-densification is high; in fact, companies can contribute significantly to the concept of re-densification and the provision of affordable social housing. There is also a growing demand in urban development promotion programs for public participation becoming a mandatory condition. However, there is also growing skepticism on the part of local politicians and planning experts about such solutions.

In Germany, a study explored the potential for re-densification through the use of space occupied by parking lots or that on existing buildings and found that some 400,000 housing units could be built on top of existing or newly constructed single-story buildings, such as retail stores, discount stores and other markets, without losing retail space. In total, taking into account other urban spaces, the same study estimated that between 2.3 million and 2.7 million units would be built (Tichelmann 2019).

The article looked at “new players” in the development of the housing sector of German cities. Potential and existing investors are described, and the potential of this type of investor in the social and affordable housing market is highlighted.

Since this article is mainly aimed at readers outside Germany, it is worth noting that Germany is a country of renters. Other studies in the literature have looked at why the percentage of renters is higher in Germany than in most European countries or the U.S., considering historical and socioeconomic reasons as well as the political system to be important (Haffner 2017; Kohl 2017; Noll 2009; Urban 2015). However, the level of rents has increased in German terms, albeit not to the same extent when compared internationally. A comparison of rents in major European cities in 2018 showed that Munich, the city with the highest rent levels in Germany, is not even listed in the top 20 (Haufe Online 2019).

The research method used is a critical analysis of literature data, as well as the results of comparative quantitative and comparative analyses. In examining the historical aspects of affordable housing, the literature was mainly analyzed, supplemented by selected newspaper articles and documents issued by the German government. In researching the involvement of commercial companies in the German housing market and gathering relevant data, the author referred to numerous German newspaper articles. Social and affordable housing is the subject of continuous and frequent discussion in German housing policy literature and in the German press.

The world’s oldest example of social housing is the “Fuggerei” in Augsburg, southern Germany. This example shows that the need to provide good housing for people who have limited access to adequate living conditions has a long tradition. The intention of Jakob Fugger in the 16th century was to support citizens of the city of Augsburg who were willing to work but had lost their property for reasons for which they were not responsible. This was assistance aimed at people who then helped themselves.

The second aspect that should be mentioned is that the “Fuggerei” in its time was a visionary housing project, creating a new style of housing with a comparatively large amount of space for tenants, their own entrances to each unit, a closed, city-like structure near the center of Augsburg.

The “Fuggerei” already demonstrated the key points of today’s affordable housing. It provided working but needy people with good housing. It created new standards for houses in a certain area within the city limits and thus influenced the development of the city (Zabel, Kwon 2019, p. 2).

Figure 1. “Fuggerei” in Augsburg, Germany, is the world’s oldest social housing project still in existence

Source: https://www.dreamstime.com/owes-its-name-to-fugger-family-was-founded-jacob-younger-known-as-rich-represents-place-where-citizens-need-image130570449, (access: 11.06.2024).

The need for affordable housing increased with the urbanization of Germany in the context of its industrialization in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Even if the need was not officially perceived, it was evident because housing units were limited to one or two small rooms, the number of people living in them was high and they were also used by strangers who, for example, paid to sleep in a bed for several hours a day. In addition, the same apartment could be used by one or two residents earning money there by, for example, sewing. Social housing as an official concept of the federal government and various German states has a history of more than 100 years. It began in 1918 with the end of World War I and the ongoing industrial transformation, bringing people from rural areas to cities.

Demand for social housing in Germany reached another peak after World War II. To meet it, the young republic opted for an object-based promotion model. The federal and state governments primarily supported facilities (housing) by creating a legal framework and financial support.

Two housing laws were passed in 1950 and 1956 (I. WoBauG of 24-04-1950, ...). These laws provided the basis for promoting social housing policies by making public funds available for the construction of rental housing for anyone who wanted to invest in this resource. In addition, the first Housing Act of 1950 already abolished rent control in newly constructed housing financed by free funds [p. 23 I. WoBauG].

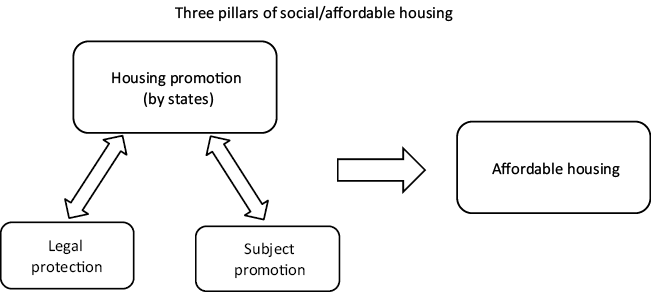

At that time, three important pillars in German housing policy could be distinguished:

A total of about nine million apartments were built in Germany between 1949 and 1965 (K.H. Peters, Wohnungspolitik, ...). About half of these (51%) were built as social housing (Ibid.). Since the commitments to social housing in Germany have always been temporary (with regard to the amount of rent, which must be based on costs, and the possibility of renting such housing, which is limited to those in need) these apartments after a while became part of the private rental market, which involved a gradual transition to market rents. This privatization process resulted in a wide range of private rental housing, which is still characteristic of Germany.

In German social housing, applicants could be financially supported directly, but mainly benefited from lower rents. The first housing law of 1950 reflected this decision. Offering interest-free construction loans from the federal and state governments’ budgets with repayment terms of 30 to 35 years definitely helped promote housing. Prospective tenants had to apply for a “Wohnberechtigungsschein” (voucher entitling them to rent social housing), which was based on certain requirements, such as income or family status, e.g., single parents (Zabel, Kwon 2019, p. 2).

Since the 1950s, the legal basis for social housing in the Federal Republic was also provided by the Second Housing Act (II. Wohnungsbaugesetz, or WoBauG). Its goal was to create a stock of housing that, with its size, furnishings, level of rent or mortgage repayment and maintenance costs, suited a broad spectrum of the population’s social groups. In addition to providing rental housing, the 2nd WoBauG also supported the acquisition of owner-occupied properties (Whitehead, Scanlon 2007, p. 91).

This law was replaced in September 2001 by the Housing Law Reform Act (Gesetz zur Reform des Wohnungsbaurechtes), which incorporates the Law on the Provision of Social Housing (WoFG). Although the new law continues to regulate the construction of rental housing (including cooperative housing) and owner-occupied housing, as well as other measures to support households that are unable to secure sufficient funds to purchase housing on the market, it marks a significant shift away from financing specific types of housing toward individual subsidies and away from socio-spatial policy toward individual care.

Figure 2. Figure based on statements by the German federal government

Source: own compilation based on Zabel, Kwon 2019, p. 2.

On the basis of the WoFG, the states enact their funding ordinances, which detail the conditions for funding and its implementation. Even though under the federal reform the exclusive legislative authority to promote social housing was transferred to the states, unless the federal WoFG is replaced by state regulations, it remains valid. At the same time, however, the federal reform also affects the financing of social housing in Germany. Until the end of 2006, the federal government made funds from its budget available for this purpose in varying amounts, but continued to pay compensation to the states until 2019. After that, however, the necessity of these transfer payments should be reviewed (Keßler, Dahlke 2009, p. 275).

It should also be noted that the German housing policy previously focused on huge direct and indirect subsidies to investors (grants and tax breaks). These have been scaled back since the 1980s, as generally high housing standards made state interference unnecessary, except for small groups with special needs. Since the late 1980s, special emphasis has been placed on specific groups rather than general policies, with particular emphasis on care for the elderly, single parents and larger families. However, with the emergence of new urban problems-including regional economic disparities, demographic changes, urban polarization and more than a million empty homes – a debate has begun about the need for and appropriate forms of social housing in a reformed welfare state (Whitehead, Scanlon 2007, p. 91).

As the economy grew, the government also decided to promote home ownership through subsidies and later tax breaks. This eventually became a major goal as well. The development of housing after World War II, along with an increasing housing supply, made it possible to deregulate the housing market, and the change of parties in government increased this development. The focus shifted to home or apartment ownership, and the importance of social housing diminished, also due to the recession in the 1970s. However, in the late 1980s, there was an increase in the number of single-person households, more people born during the baby boom years established their own households, and after 1989 (German reunification), some of the population from East Germany and Eastern Europe moved to West Germany, where the number of housing units did not increase. The government responded to this development with new programs such as the “Soziale Stadt” (Social City) and “Stadtumbau Ost” (Rebuilding the City East).

In 2007, when demographic developments showed a slow population growth, an aging population and a definite need for fewer housing units, the government amended the “Grundgesetz” (German Constitution). Responsibility for social housing was transferred to the states; the federal government henceforth supported the states through compensation payments: a model that legally ended in 2019 (Zabel, Kwon 2019, p. 3).

The governments of West and East Germany faced the same challenges. Both were committed to providing living space for their populations. However, the Soviet authorities in East Germany insisted on providing long-term war reparations, which resulted in the dismantling and liquidation of large industrial plants. At the time, housing consisted of creating living spaces near rebuilt or newly built industrial estates, especially in the vicinity of resource industries such as coal mining.

In the 1950s, German cities had a “loosely structured spatial environment” to include green spaces while promoting urban traffic flow. However, the so-called “loose city model” persisted in the east, where efforts continued to favor green spaces and areas with traffic (Zabel, Kwon 2021).

In the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the so-called “Mass Housing” was financed under the state economic plan. Built by a state monopoly, more than 2/3 of all new housing was managed by municipal administrations as rental units. About 25% of these housing units were organized by workers’ housing cooperatives, and about 5% of public funds were allocated for ownership of housing for privileged groups.

By the late 1980s, East German housing stock was dominated by housing stock that was the product of three post-war construction periods (Whitehead, Scanlon 2007, p. 91).

The first of these, in the 1950s, were the so-called “working-class palaces,” followed by a brief International Moderne phase in the 1960s, when the quality of housing was comparable to Western social housing. In contrast, mass industrial production of so-called “big plate” buildings began in the peripheral New Residential Areas (Neubaugebieten) in the 1970s, which later spread to eastern German inner cities.

However, as public dissatisfaction with urban neglect and housing conditions increased, the working class “privilege” of living in large new housing developments lost its appeal, especially as a market for quality housing emerged after German reunification in 1990. Since new and renovated apartments of various types appeared, many neighborhoods of GDR-era municipal buildings were increasingly abandoned by the better-off sections of society. Only elderly and poorer residents remained in the units, while groups of young people with limited financial resources began moving into the cities.

Mass housing in the GDR, which was converted from “people’s property” to communal housing at the time of reunification, was not social housing in the legal sense. The volume of housing in the German Democratic Republic was about half or 1/3 of the West German level; only since 1976 has the volume of housing in the two German states been equalized [Cornelius Julia and Rzeznik Joanna, National Report for Germany, TENLAW (Tenancy Law and Housing Policy in Multi-level Europe, p. 3)]. In the East, legal restrictions on social housing applied only to rental and cooperative housing and many single-family homes built under new laws after 1990 (Whitehead, Scanlon 2007, p. 92).

Social housing in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) consisted of both highly subsidized rental and cooperative housing in city blocks and a significant number of ownership apartments in smaller neighborhoods and on the outskirts in single-family homes. Social rental housing was initially built in areas devastated by the war and only later moved to the urban suburbs, returning to them with the advent of urban renewal.

Municipal and cooperative housing companies (often closely linked to municipalities) were among the most important players in German housing policy. From the 1980s onward, the states’ housing programs were increasingly opened up to individual and institutional private investors. This embrace of the private sector was both an attempt to secure more private financing and a response to public protests against flawed urban renewal strategies and financial scandals.

In Germany social housing has never been specifically targeted at the poor and specifically designed for this social group. In fact, the cost of social housing (whether rent or mortgage payments) was usually beyond the reach of the poor; the sector was designed to provide “decent” housing for the largest group of workers and the lower middle class. Apart from a decline in quality during the period of mass production in the 1970s, West German social housing was always at the forefront of architecture and urban planning.

The surface area of these apartments was large, in view of which these apartments were therefore never perceived as lower-class housing. Particularly since the mid-1980s, builders have sought to construct attractive homes with high environmental standards, in part to serve as a model for market housing (Whitehead, Scanlon 2007, p. 92).

Former German housing programs were designed to effectively alleviate a severe overall housing shortage (IWU 2005: 7–8). Only later did social housing programs focus on specific target groups, and their share of the total number of housing units delivered began to decline (Kofner 2003, pp. 322–328). In 2001, the previous social housing legislation and programs were replaced by a comprehensive structure of legal support for housing, which is characterized by several levels of action, funded by the federal government and the German states.

Under the federal system, the federal government provides the overall legal and institutional basis and sets goals for social housing provision. It also provides financial assistance to the states, which are constitutionally responsible for housing and have their own local housing policies. Due to high vacancy rates in some regions of Germany, emphasis is being placed on the rehabilitation of existing properties and the acquisition by German municipalities of rights to temporary social housing on the open housing market. The aim of such measures is to limit the formation of potentially discriminatory clusters of homogeneous social housing. This strategy is used by those states and municipalities where relatively few households require public housing assistance. (Whitehead, Scanlon 2007, pp. 93–94).

The steadily declining importance of social housing is due to the successive reduction of federal subsidies and the temporary nature of these subsidies, whose durations are becoming shorter over the decades. Subsidies are usually provided in the form of publicly subsidized mortgages. Once the loans are repaid, individual apartments lose their social status (i.e., special pricing and allocation obligations) and can be freely rented to any tenant regardless of income. For a long time, the number of housing units losing their social status each year was much higher than the number of social housing units newly approved by public financing agencies (Kofner 2017, p. 63).

In 2015, not even 1/3 of the 51,000 approved social housing units were newly built rental housing. The share of new construction in the total number of approvals has been very small for a long time (consistently below 40% since 2006, about 1/3 since 2013). Nowadays, there are no more “social landlords” in Germany, only profit-oriented landlords who control part of the social housing stock.

It seems doubtful that the qualitative goals of subsidizing social housing can be achieved with such ownership structures. The general principles of financing listed in Section 6 of the WoFG place particular emphasis on the diversification, sustainability and effectiveness of social housing subsidies. This relates to an important principle of German social housing policy, which is the pursuit of “socially stable neighborhoods.” In view of this, the target group for the promotion of social housing are households that are unable to secure adequate housing on the market and are in need of state support. In particular, the programs support low-income households, families and other households with children, single parents, pregnant women, the elderly, the homeless and other persons in need (§ 1(2) of WoFG).

The problem of the shortage of affordable housing, especially in areas with low vacancy rates and high rents, should be addressed not only through subsidies for social housing.

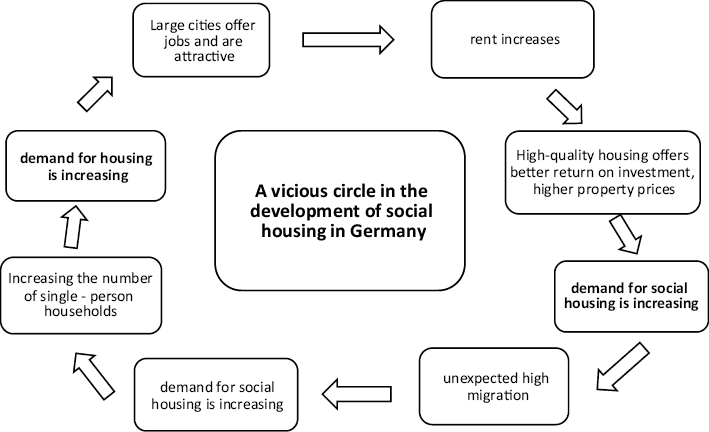

The cause of the housing shortage is complex and consists of many elements, from the aforementioned change in the government policy due to, among other things, migration to a vicious cycle of investment in quality housing in favored large cities, leading to higher rents and a greater shortage of affordable housing. The housing problem in Germany, which was thought to have been solved, has returned (Holm 2014; 2018a). Meanwhile, the development and maintenance of public spaces is an essential part of urban redevelopment and urban planning. Therefore, federal governments and the states cannot withdraw funding; rather, they must counter the risks posed by private investors who focus solely on their individual interests (Wekel, Ohnsorge, Zdiara 2018). Studies in the literature indicate that this also applies to housing, especially social housing.

Between 2007÷2019, the situation in Germany changed, with demand for social and affordable housing increasing in large cities and neighborhoods near large cities. The reasons for these changes are varied. With an overall increase in the number of housing projects, housing companies became more interested in building quality housing, which provided them with better margins. Legislation was introduced (at the local or federal level) that no housing project would receive a building permit unless 30% of the units were dedicated to social housing. Companies often found ways around this provision. As a result, the permitting process is usually slow. People who live in social housing do not have to move out, even if they no longer meet the regulations. The rules only apply when moving into a new apartment. Meanwhile, more and more target groups have become eligible for social housing, such as single-person households, migrants, the elderly and people from lower-income groups.

Figure 3. The vicious circle in the development of social housing in Germany

Source: own study

Compared to all other options for encouraging new housing, social housing is the housing instrument with the greatest spatial reach. Therefore, a tenfold increase in the annual number of social rental housing units delivered to 150,000 units per year could halt the further decline of the social housing sector and make a major contribution to the necessary relaxation of tight housing markets.

With an assumed net present value of subsidies of €35 000 per a housing unit, more than €5 billion of public funds would be needed for this per a program year (Kofner 2017, p. 69).

In summary, the modern type of social housing support is narrow, cost-effective and decentralized. Currently, social housing programs are characterized by short commitment periods, rents at the lower limit of the LRR (local reference rent), income-oriented subsidies, a small spatial distribution of the housing units being delivered, including mixing them with privately financed housing, and a clear and consistent preference for creating social housing in existing housing stock – the concept of urban densification.

Models for bridging the gap between housing supply and housing needs are based on the assumption that this is not possible with the government support alone, private investors are also crucial here. So far, private investors have been found in companies dedicated exclusively to this task, construction companies, developers, etc. However, new opportunities may arise for companies for which residential offerings in city centers are essential to their operations, and so they have a common interest with municipal authorities (municipalities). For several years now, commerce has invested in real estate not only to build retail branches, but also in conjunction with housing.

Municipalities are very interested in this type of project, where valuable space in city centers above existing single-story stores is used for housing. The number of permits in which a new supermarket needs to be combined with a residential building or, for example, a day care center, seems to be increasing. In Berlin, for example, building permits are issued only if the new store fits into the city’s urban densification (re-densification[1]) concept and if it provides a hybrid use (Zabel, Kwon, 2019, p. 4). At this point, it is worth discussing the three interacting concepts of urban densification (densification), de-densification (de-densification) and re-densification (re-densification) on the grounds of relational geography.

In the current of the concept of relational geography, we can mention three concepts of urban densification: densification, de-densification and re-densification. To understand these concepts in a broader sense, it is necessary to discuss the concept of relational geography.

The basis of relational conceptions of cities is the rejection of an essentialist Euclidean understanding of space in favor of a relational view that emphasizes dependencies and connections between different places, processes and activities (Healey 2004; Madanipour 2010). Relational geography challenges not only the framing of the city as a homogeneous, relatively closed, and thus locally policyable whole, but also the notion of a hierarchy of spatial levels – from the global, to the geo-regional, to the national, to the regional, to the urban, to the very local levels of the neighborhood, estate and apartment building. Relational thinking about scale is embedded primarily in the distinction between hierarchical and network geographies in which scales function as interfaces between global and local processes (Amin et al. 2003; Massey 2005; Healey 2006 and Miciukiewicz 2011, p. 171).

The processes of densification, de-densification and re-densification in space and time are central to how cities emerge and transform (McFarlane 2020, p. 317). It is important to note that as the world becomes more urbanized, the dominant trend is urban expansion rather than urban densification. The World Resource Institute (2019) noted three related factors: developers speculating on land on the outskirts of cities as a way to expand the real estate economy into new areas; a lack of specificity in state or city policies and regulations regarding the location of new housing or other developments; and a generally weak set of property rights among residents and landowners on the urban fringe (p. 317).

As Shlomo Angel has shown, using demographic data and satellite maps, urban sprawl is outpacing densification worldwide. This means that the area of cities has increased at a faster rate than their populations (p. 317).

Similarly, Roger Keil (2018) has argued in his scholarly work that it is necessary to rethink both density and sprawl (rethink both density and sprawl) in order to move away from dichotomies of assumptions – for example, that dense development equals more environmentally sustainable high-rises and suburbs equals density-unsustainable lots – toward a more nuanced and complex awareness and geographic framework. “In a scenario in which millions of new residents are yet to arrive in many already dense urban regions over the next generation, we cannot afford to view either suburbs or density in the current way” (Keil 2018, p. 317).

This means that while cities in a sense are densifications in themselves – they occupy about 3% of the planet’s surface and are home to the majority of the world’s population – and while in a basic sense that is what they serve, there is no simple connection between cities, urbanization and densifications.

In fact, urbanization, as a process of creating and transforming urban and non-urban spaces, sometimes proceeds by densifying the city’s space, for example, by extending its territorial boundaries to new peripheries or through new economic links to other places outside the city (including, of course, rural geographies). As Neil Brenner and Christian Schmid have argued in a number of works, the city may or may not be an important arena for urbanization (Keil 2018, p. 317).

The concepts of densification, de-densification and re-densification from the perspective of the relational geography of the city are central here, as the city is an important and powerful arena in which the coordination, development, politicization and transformation of these processes take place, but it is relational geographies that become the focus of study. The processes of de/re densification do not occur in isolation. They bring into relation multiple temporal spaces within and beyond a given place including through global political economic relations, migration, environmental processes, the circulation of ideas, knowledge and practices, and forms of technological interconnectedness (Keil 2018, p. 318).

Arguments in favor of densification are ubiquitous and put forward by influential social groups. The idea of building dense urban settlements – often, but not always, in the form of skyscrapers – has become the mantra of modern cities, with the promise of lower carbon emissions, proximity to amenities and social life, economic creativity and affordability. For example, an influential economist, Ed Glaeser (2012) has argued that the accumulation of residents in skyscrapers is an economic necessity for affordable housing in central city locations. The recent rush to create high-density skyscrapers around the world, from New York, London and Manchester to Mumbai, Phnom Penh and Jakarta, is often coupled with exclusive real estate ventures, combining the state and the speculative economy – often with global reach – into powerful arrangements that hijack urban contemporary and future spaces. Too often, the public realm is diminished, as community resources such as playgrounds, libraries and parks are sacrificed for the profits of developers, and an increasing number of residents look at housing they will likely never be able to afford (McFarlane 2020, p. 319).

For De Boeck, density (densification), is a form/process of accumulation and fusion in which people and things are combined, connected and form relationships through multiple trajectories, forms and processes. The city is a crucible that combines these relationships and rejects them from each other, de/re-densifying uneven spatial development operating at different speeds. All too often, however, what comes together is an increasingly commoditized city: often prohibitively expensive land and housing, urban space turned into an investment vehicle, excluding high-end consumer projects and spaces. Housing conditions are set by dominant political economies and cultural politics that want to shape urbanization as it is, or profit from it.

What is crumbling is both the very principle of urban community and public space, as well as the ability of the urban poor, and in many cases the lower middle class, to secure free market housing, lives and shares in cities around the world (especially in the centers of larger cities). The period of building the modern city based on public and civic provision of housing needs has given way to “processes of dismantling,” particularly displacement and disinvestment (McFarlane 2020, p. 320).

The German federal government has said that the demand for affordable housing cannot be met by the government alone, but also by relevant state programs. According to the German government, a combination of affordable housing offered by the private sector and social housing will be the solution to creating sufficient supply for existing demand. However, the resulting logical question about the definition of “affordable” in this context cannot be answered.

Table 1. Inadequate supply of housing, especially for lower income earners in the cities of Berlin and Munich

| City | Number of households with income <60% of average income | Under-supply (in %) |

|---|---|---|

| Berlin | 221 758 | 60 |

| Munich | 50 241 | 60 |

Source: own compilation based on Zabel, Kwon 2019, p. 4.

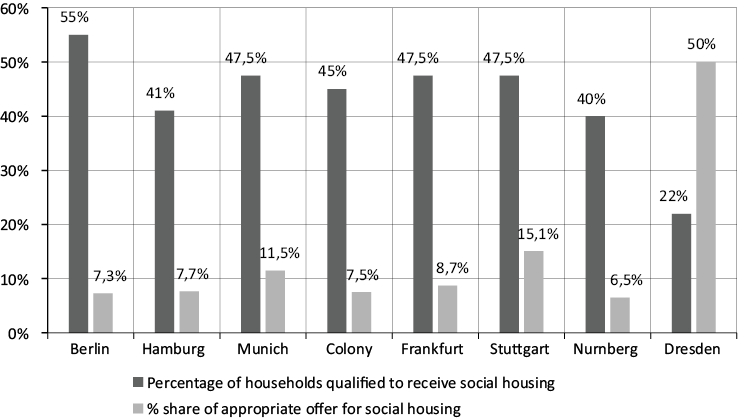

Figure 4. Social housing – high demand – low supply (as of 2019)

Source: own compilation based on Zabel, Kwon 2019, p. 4.

In 2014, the Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, a federal institution, calculated the need for affordable housing at about 1.5 million in 77 major German cities for residents with 60% or less of average income. In 2015, a government institution calculated the need for 1.6 million new affordable housing units over six years. It should also be noted that the waiting period for housing varies from the official six months; in fact, it ranges from less than a year in Munich to five years in Frechen (near Cologne). In contrast, in larger cities, the demand for social housing far exceeds its offer (with the exception of the city of Dresden) – see Fig. 4 (Zabel, Kwon 2019, p. 3).

In Germany in 2018, two discounters Aldi Nord and Lidl surprised with an announcement that they would provide housing, respectively, a crèche for children at their branches.

Retail companies realize that the shopping habits of the younger generation have changed. Their interest in going green is high, and so they prefer to do their errands and shopping close to home, walking or biking.

This requires stores in the city, rather than on the outskirts, as previously provided by, for example, furniture stores, or in shopping malls, as preferred by ALDI and Lidl. In cities, space is limited and expensive, single-store buildings are not an option. Municipal authorities support this because they want cities to be vibrant and friendly to residents.

Aldi Nord is one of Germany’s large discounters, with a turnover of €11.73 billion in 2017. According to the current data, the company is organized into 32 regional companies that operate 2,240 stores with 35,000 associates and 2,500 trainees.

Figure 5. Aldi Nord, the discounter, plans to combine its own stores with affordable housing in Berlin

Source: Aldi Nord.

Aldi has announced two projects. They are planning 30 projects in Berlin, the first of which will have between 50 and 60 units. Rental prices for 30% of the units will be limited to €6.50/m², while the remaining 70% will cost a maximum of €10/m². The latter value corresponds to the lower limit of Berlin’s Mietspiegel (the rent index for all of Berlin).

Lidl, is Germany’s largest discount retailer with net sales of €20.4 billion in 2017 in Germany, €68.8 billion worldwide. The company, according to its own data, is organized in 38 regional companies with 3,300 stores. They employ more than 70,000 associates (Zabel, Kwon 2019, p. 5).

Figure 6. Space-saving design meets convenience: The Lidl-Metropolfiliale

Source: Lidl Germany.

Another Lidl project is the construction of “metropolitan stores,” which need much less space because parking will be under the building. More metropolitan stores, the first with 110 and 70 residential units in Frankfurt, are already planned and construction has begun. In this way, the city of Frankfurt can improve the quality of its infrastructure through densification. Lidl has announced this type of project for Hamburg as well, including a hotel and a day care home (p. 5).

Thus, the planned apartments are not entirely a social housing project, but the maximum prices are limited at the gross level of apartments offered, and 30% are offered at the social housing level. Lidl is planning a similar project, but so far rental prices have not been officially announced. The company only states that rents will be at the same level as in the area.

Shopping habits, especially among the younger generation, have changed. Global furniture company IKEA recognizes the need to place stores closer to customers, who in large cities often no longer use a car, but want to easily reach their destinations by bicycle or public transportation. For this reason, IKEA is also thinking about new concepts, planning an entire urban quarter. One new store has already been built in the center of Munich. Other projects will include apartments, which will have an impact on the urban environment (p. 5).

Such projects such are in high demand. The city of Berlin held a Supermarktgipfel (supermarket summit) in 2017, to be repeated annually. In doing so, it follows Munich, where such a meeting was organized in October 2016. The mayor of Munich invited representatives of the largest discount stores to convince them of the idea of dogging the city with new housing projects, but also new parking spaces through new buildings on stilts.

Osnabrueck, a city of 163,505 residents in 2017, also invited the Supermarktgipfel. The city of Leipzig is also pushing the idea of using one-story high buildings for redensification and using this space for housing or facilities for better infrastructure (p. 6).

This article describes some aspects of changes in social and affordable housing in Germany and new partners entering the rental market. Social housing has a very long tradition in Germany, but as we understand it today, it began after World War I with another peak after World War II. In the decades that followed, there were many changes, such as demographic shifts and sweeping changes in household structure (more individual households).

In response, the German government swiftly adapted by shifting the focus of subsidies from promoting private homeownership to supporting houses and apartments. Subsequent programs demonstrated adaptability by introducing tax credits instead of subsidies and implementing new housing initiatives to address evolving needs.

In 2007, German policymakers and experts believed that the demand for social housing had diminished, leading the federal government to modify legal conditions and transfer responsibility to the states, resulting in the discontinuation of most housing support programs.

However, due to both internal migration within Europe and immigration from other countries, the overall population has only experienced a slight growth but has significantly increased in larger cities. The rise in single-person households and the process of gentrification have contributed to an unforeseen surge in demand for affordable housing in recent years.

To tackle the limited space available in urban areas, municipal governments have had to explore alternative financing models for affordable housing. In order to stay competitive with other German cities, they must prioritize the provision of high-quality living spaces while also considering sustainability and social infrastructure. This shift in the promotion of affordable housing has resulted in a decline in the number of housing investment companies. As a result, cities are now open to forging new partnerships, including collaborations with commercial companies that recognize the changing consumer preferences, particularly among young people.

These companies require space in city centers and are offering to integrate their stores with residential units, nurseries, hotels, or public parking lots. This initiative by German commercial enterprises to offer apartments in city centers reflects a closing of the circle, reminiscent of the historical concept of “Fuggerei”. Currently, these projects are considered niche and it is too early to determine their impact on the future of affordable housing in Germany.

As a result, apartment management has become a new responsibility for commercial companies. The future will reveal whether they can successfully manage this task or if they will eventually sell the buildings to specialized apartment management companies. These new projects have the potential to alleviate the challenging housing situation and contribute to urban densification, thereby revitalizing city centers and making them more livable and attractive by combining residential, commercial (such as shopping), and working spaces.

However, it is important to note that planning decisions are subject to intense debate among various social groups, including residents, environmentally-focused organizations, industries, and small business owners. Some may strongly oppose the idea of large retailers having an increasing influence on urban renewal (Zabel, Kwon 2019, p. 8).

Answering the research question raised at the beginning: “Can private investment increase the availability of social and affordable housing?” it can be concluded that private investment has the potential to increase the availability of social and affordable housing. To date, financing models for social housing have relied mainly on the government support, but the role of private investors in this area is becoming increasingly important.

Traditionally, private investors have been found mainly in companies specializing in housing (developers) and similar industries. However, new opportunities are also emerging for companies for which residential offerings in city centers are important to the conduct of their business, creating a common interest with city authorities. An example of this is large discounters such as Aldi Nord and Lidl, which have begun to invest in residential real estate rather than just retail branches. German cities are interested in these types of projects, as they allow a valuable space in city centers to be used for residential purposes.

Also worth mentioning is the trend of changing shopping habits, especially among the younger generation, who prefers to shop locally using means of transportation such as bicycles and public transportation. As a result, retail companies such as Aldi, Lidl and even global brand IKEA are considering placing stores closer to the customers, in city centers, to meet their expectations. This shift in the approach of retail companies opens up the possibility of working with the city governments to create social and affordable housing in urban centers.

Retail companies can contribute to increasing the supply of social housing, but this requires adjusting business strategies accordingly so that the profitability of their core business is not negatively affected. This type of project can be pursued by companies such as Aldi and Lidl or IKEA as long as it involves additional benefits, such as enhancing a brand image or making more efficient use of urban space.

As already indicated, these units will not be typical social housing projects, but the capping of prices to a maximum limit and the offer that 30% of the units offered will cost as much as a social housing unit will create an offer that is very favorable to households with unmet housing need (Zabel, Kwon 2019, p. 5). However, without additional incentives in the form of tax breaks or government subsidies, it is difficult to expect the private sector to be fully committed to providing social housing on a scale that could significantly improve the real estate market.

In order for private investment to effectively increase the availability of social housing on a large scale, it is necessary to develop a model in which the involvement of private investors in housing is supported by the state and at the same time does not negatively affect their commercial activities.

The German federal government has also recognized the need to cover the demand for affordable housing not only by the government, but also through some state programs and private investment. Accordingly, new housing programs and flexibility in tax credits for private investors have been introduced.

It is worth noting that the demand for affordable housing is significant, and the number of social housing units is not sufficient, especially in larger cities. Therefore, cities are trying to find new financing models to increase the availability of this type of housing. In this context, private investment, both from commercial companies and other investors, can play an important role in meeting this demand.

Amin A. (2004), Regions unbound: Towards a new politics of place, “Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography”, 86(1): 33–44.

Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte (APuZ) (2014), Wohnen, 64. Jahrgang, 20-21/2014, 12. Mai 2014, Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (BPB), Bonn.

Gliemann K., Szypulski A. (2018), Integration von Flüchtlingen – Auch eine Frage der Wohnunterbringung, [in:] L.C. Kaiser (ed.), Soziale Sicherung im Umbruch: Transdisziplinäre Ansätze für soziale Herausforderungen unserer Zeit (pp. 105–123), Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden.

Haffner M., Hegedüs J. (2017), The Private Rental Sector in Western Europe, [in:] J. Hegedüs, M. Lux, V. Horváth (eds.), Private Rental Housing in Transition Countries (pp. 1–20), Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Haufe Online R. (2019), Studie: Deutsche kaufen und mieten vergleichsweise günstig.

Healey P. (2004), The treatment of space and place in the new strategic spatial planning in Europe. Steuerung und Planung im Wandel: Festschrift für Dietrich Fürst, pp. 297–329.

Healey P. (2006), Relational complexity and the imaginative power of strategic spatial planning, “European Planning Studies”, 14(4): 525–546.

Holm A. (2018), Die Rückkehr der Wohnungsfrage, Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung.

Keßler J., Dahlke A. (2009), Sozialer Wohnungsbau, [in:] A. Krautscheid (ed.), Die Daseinsvorsorge im Spannungsfeld von europäischem Wettbewerb und Gemeinwohl: Eine sektorspezifische Betrachtung (pp. 275–289), VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden.

Kofner S. (2003), Die Formation der deutschen Wohnungspolitik nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, Teil III, “Deutsche Wohnungswirtschaft”, 55(12): 322–334.

Kofner S. (2017), Social Housing in Germany: An Inevitably Shrinking Sector, “Critical Housing Analysis”, 4(1): 61–71.

Kohl S. (2017), Homeownership, Renting and Society, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, London–New York.

Madanipour A. (2010), Connectivity and Contingency in Planning, “Planning Theory”, 9(4): 351–368.

Massey D. (2005), For Space, Sage, London.

McFarlane C. (2020), De/re-densification, “City”, 24(1–2): 314–324.

Miciukiewicz K. (2011), Urbanizacja natury: w stronę relacyjnej ekologii miejskiej, “Przegląd Socjologiczny”, 60(2–3): 167–186.

Noll H.-H., Weick S. (2009), Wohnen in Deutschland: Teuer, komfortabel und meist zur Miete; Analysen zur Wohnsituation und Wohnqualität im europäischen Vergleich, “Informationsdienst Soziale Indikatoren”, 41: 1–7.

Pestel Institut für Systemforschung e.V., & VHT Institut für Leichtbau | Trockenbau | Holzbau. (2019), Deutschlandstudie 2019, Darmstadt.

Ringwald J. (2020), Sozialer Wohnungsbau im Kontext deutscher Wohnungspolitik seit 1918: Einflussfaktoren auf die Neubautätigkeit im sozialen Wohnungsbau (B.A), Katholische Hochschule Freiburg.

Schmitt G. (2017), Die Wohnungsfrage in der Stadterneuerung, [in:] U. Altrock, D. Kurth, R. Kunze, G. Schmitt, H. Schmidt (eds.), Stadterneuerung im vereinten Deutschland – Rück- und Ausblicke (pp. 97–116), Springer Fachmedien, Wiesbaden.

Tichelmann K.U., Blome D. (n.d.), ISP Eduard, Technische Universität Darmstadt.

Wekel J., Ohnsorge D., Zdiara A. (2018), Planungspraxis kleiner und mittlerer Städte in Deutschland – Neue Materialien zur Planungskultur, “Projekte”, 51: 251.

Whitehead C., Scanlon K. (2007), Social Housing in Europe, London School of Economics and Political Science, London.

Zabel R., Kwon Y. (2021), Evolution of urban development and regeneration funding programs in German cities, “Cities”, 111, 103008.

Zabel Y., Kwon S. (2019), The transition in social housing in Germany – New challenges and new players after 60 years, “Architectural Research”, 21(1): 1–8.

Problemu braku odpowiedniej liczby mieszkań społecznych i przystępnych cenowo nie jest możliwy do rozwiązania wyłącznie przy udziale rządu i władz lokalnych – kluczowi są również prywatni inwestorzy. W ostatnim czasie pojawiły się nowe możliwości dla firm, których kluczem do prowadzenia działalności jest odpowiednia oferta mieszkaniowa w centrach miast. Firmy zajmujące się handlem inwestują na rynku nieruchomości nie tylko w celu budowy nowych filii handlowych, ale również w połączeniu z budownictwem mieszkaniowym. Niemieckie miasta są bardzo zainteresowane tego typu projektami, w których cenna przestrzeń w centrach miast nad jednopiętrowymi sklepami jest zagospodarowywana na mieszkania. Od 2018 r. sieci sklepów detalicznych łączą swoje interesy handlowe z interesami mieszkaniowymi w mieście. Postawione pytanie badawcze brzmi: Czy prywatne inwestycje mogą zwiększyć dostępność mieszkań społecznych i przystępnych cenowo?

Słowa kluczowe: mieszkalnictwo społeczne, niemiecka polityka mieszkaniowa, zagęszczanie zabudowy, prywatni inwestorzy, zrównoważony rozwój