https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5826-7942

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5826-7942

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2930-8469

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2930-8469

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2138-398X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2138-398X

Current global economic challenges have stimulated public demand for coordinated activities at a transnational level (as evidenced by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis). In this context, academic discourse and the forums of various multilateral organizations have invoked the concept of global public goods (GPGs). This paper explores the practical realization of the GPGs concept within the global structures of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), assessing the extent to which the wealth of services provided by the Fund may actually be considered GPGs. Approaching the subject from a theoretical perspective, the paper draws on analytical evaluations of relevant documents and IMF data sources, as well as empirical findings derived from semi-structured in-depth interviews (IDI) with representatives of international organizations (including the IMF) in Washington, DC. The findings suggest that the IMF provides a diverse array of products supportive of international financial stability (particularly ‘best-shot public goods’), and may therefore be regarded as exemplifying the GPGs concept. During times of relative global economic stability, IMF expenditure shifts toward technical support and monitoring, placing the organization in a role more akin to a provider of pure public goods. However, despite the IMF enjoying a number of competitive advantages (and resources) that would seem to preordain a role as a major GPGs provider, the GPGs concept is only marginally evoked in the organization’s publications and activities. Moreover, certain elements of the IMF’s model of operation drastically reduce the organization’s current operating capability as a GPGs provider.

Keywords: global public goods, IMF, global financial stability, multilateral cooperation

JEL: F53, H51

Transformations in the modern global economy point toward an increased interest in (and demand for) the transnational coordination of activities, with modern societal problems – such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic – tending to transgress state borders. Against this backdrop, the concept of global public goods (GPGs) has been frequently evoked in the academic discourse and by assorted multilateral forums. Specifically, the GPGs concept has been analyzed as a possible response to emergent global-scale threats (e.g. Bucholtz, Sandler 2021; EPG 2018; Gallagher, Kozul-Wright 2019; Kaul et al. 2003; Sandler 1997; Villafranca 2014). Here, aside from the ‘typical’ areas where demand for GPGs can be seen (such as environmental protection, public health, security), attention must be paid to the realms of macroeconomics and finance (Barrett, Dannenberg 2022). Today, even minor disturbances in individual state economies can impact other countries and regions (the so-called contagion effect), with such effects potentially detrimental to the entire global economy. These observations would suggest a need to look afresh at the operational organization of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), using a wider lens than previously employed in more traditional approaches (Edwards 2008; EPG 2018; Joyce 2013). In terms of such an approach, the IMF represents not only a source of emergency credit, remedies, and technical support, but a potential provider of GPGs. In fact, as suggested by Jim O’Neill in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the IMF ought to ‘start regularly opining on health disease and system preventiveness as part of its annual article IV of Agreement, to force countries to pay more attention’ (Wei 2020).

However, the IMF has for more than two decades been subject to criticism regarding its governance principles (e.g. Boorman 2008; Buira 2005; Paloni and Zanardi 2006; Woodward 2007) and its adopted mode of operation (e.g. Beazer, Woo 2016; Bird 2011; Feldstein 1998; Eurodad 2006; Jensen 2004; Meltzer et al. 2000; Radlett, Sachs 1998; Stiglitz 2002). While many criticisms raised against the IMF – both those stemming from the IMF’s own Independent Evaluation Office (IEO) (e.g.: IEO 2013, 2014a, 2014b, 2016) and those by third-party experts and researchers (cf. Lane, Philips 2002; Lorenzo, Noya 2006; Wróblewski 2009) – have been disproved or refuted in scientific analyses, they have nevertheless contributed to trust in the IMF being eroded, further emphasizing the organization’s ongoing identity crisis. Even so, despite the widely proclaimed limitations of the IMF’s significance and utility, particularly in relation to the drastic decline in demand for IMF credit in the period 2001–2007 (Weiss 2013), the organization can potentially play a significant role in activities undertaken at a global scale.

This paper aims to examine whether and how the GPGs concept can be realized in the IMF’s global structures, as well as the extent to which the wealth of services currently provided by the organization may actually be considered GPGs. Approaching the subject from a theoretical perspective, the paper draws on analytical evaluations of relevant documents and IMF data sources. The empirical base for this study consists of varied interview material drawn from 11 semi-structure in-depth interviews that were conducted in Washington D.C. in September 2018 with two sets of experts: (1) senior officials in the IMF, both from the staff and from the Board; (2) senior officials from other multilateral institutions (World Bank, IADB). The purpose of choosing such informants was to investigate whether the IMF activities reveal a real GPG approach (exploring “insider knowledge”). This approach, in our view, offers an original perspective on the IMF’s ability to implement the GPGs concept in practice. The paper is structured as follows. First, a theoretical introduction of the concept of GPGs is provided. Next, the nature of global financial stability (as the main area of the IMF involvement) in the light of the GPGs concept is evaluated. This is followed by an analysis of IMF products in a GPGs context, consideration of the IMF’s competitive advantages in GPGs provision, and an examination of the problems and limitations of IMF GPGs creation. The paper closes by outlining the main conclusions drawn from the study.

The rise of GPGs as an issue of academic debate (and, to some extent, political discussion) dates back to 1990s, stimulated by the period’s emergent globalization processes and their associated challenges. In 1999, Kofi Annan – then Secretary-General of the United Nations – referred to GPGs as the ‘missing term of the equation’, in recognition of the growing significance of certain collective transnational activities. It should be noted, however, that GPGs as a concept is deeply rooted in the microeconomic theory of public goods, formulated in the 1950s by Samuelson (1954) and then expanded upon by Musgrave (1959). Moreover, it should be stressed – after Cornes and Sandler (1986), as well as Musgrave and Musgrave (2003) – that the concept is a continuation of the idea of public goods, a well-established element of classical economic studies dating back to works by David Hume and Adam Smith. Thus, before proceeding to a full characterization of GPGs, it is helpful to briefly summarize what public goods in this sense entails. In general, public goods (in contrast to private goods) are characterized by two substantial theoretical attributes: non-excludability and non-rivalry. The former attribute (non-excludability) means that producers (providers) of public goods have no capacity to exclude particular recipient segments from consuming such goods alongside other recipients. Even if exclusion were technically feasible, the associated cost of such an action would render it – from an economic point of view – irrational. As Musgrave and Musgrave (2003) put it, such an exclusion becomes ‘impractical’. The latter attribute (non-rivalry) holds that consumption of a public good by an additional recipient does not reduce existing users’ enjoyment of the good (i.e. it does not in any way limit the good’s availability to other participants). This means that provision of a public good to additional consumers can be obtained at no extra cost: ‘expansion of a consumer base generates benefits at a zero marginal social cost’ (Kanbur et al. 1999, p. 61). In other words, the marginal cost associated with consumption of an additional unit of a public good, once produced, equals (or approaches) zero. Classical examples evoked in this context include the operation of a lighthouse, clean breathable air, and public knowledge (barring patent rights limitations). It should be noted, however, that ‘pure’ public goods are considered a rare exception in any economy (Cornes, Todd 1994), with the majority of public goods actually taking the form of ‘impure’ public goods – that is, they possess only one of the two attributes described (non-rivalry or non-excludability). In addition, while the approach postulated by Samuelson tends to dominate the theoretical discourse on public goods, promising attempts have been made to approach the subject from other angles. Buchanan (1968), for example, argues that public goods are those provided solely by political organizations (i.e. organizations of collective cooperation). Thus, qualifying goods as public in character is also, in effect, a political process of social negotiation, and can be directly related to the socially identified demand for such goods. Moreover, as Cowen (1985) observes, many goods ‘become’ public rather merely ‘being’ inherently public, and so can be seen as a political manifestation of a particular social construct and/or institutional context.

In this light, it is worth emphasizing the fact that GPGs are (at least from a theoretical perspective) generally regarded as particular public goods provided (and analyzed) at a national level (see Cornes, Sandler, 1996; Kaul et al. 1999; Sandler 1997). In addition, they are non-rivalrous and non-exclusive in the sense that they can be consumed by the majority of – or, in ideal settings, all – countries. Smith and others (2003) argue that once these goods have been produced, they may be accessed by all countries without limitation, as practical exclusion is either impossible, burdened by excessive cost, or outright irrational (as the cost of their production has already been incurred). Typical examples of GPGs in this context include climate, knowledge, global health protection, preservation of biodiversity, and even multilateral trade rules.

In effect, GPGs may be viewed as domestic public goods that have ‘gone global’, or that have a strong international cooperation component (Kaul et al. 2003). This can be seen as corroborating the perspective that scientific disputes on the nature of GPGs should be well-rooted in the theory of domestic public goods. More importantly, domestic public goods are often embedded within international contexts. For instance, global financial stability may, to an extent, be approached as the sum of individual countries’ domestic activities. However, these activities – introduced in the context of international standards, such as those of the Basel Committee – also contribute to stability as a product that transcends state borders. Aside from such ‘national going global’ public goods, Kaul and others (2003) highlight two other types of GPGs: natural global commons (such as the ozone layer, solar energy, outer space), which are inherently global and formed independently of human activity (with another important characteristic being that they are ‘produced’ through effective protection), and global conditions and policy outcomes (such as world peace or global health protection). While the latter type of GPG is associated with decidedly more abstract goods, their global provision requires a high level of accord between activities introduced at a national level (Kaul refers to this as ‘internalizing externalities’). In practical terms, the majority of contemporary global challenges take the form of global public goods (or, according to another perspective, global public bads). In addition, as postulated by Sandler (1997), a majority of GPGs have the power to affect the wellbeing of future generations, which further compounds their production processes, as it not only requires collective and concerted activity in the present, but forces countries to apply a long-term perspective. Barrett (2006), meanwhile, sets out the potentially large differentiation of GPG-type products: while some (such as climate change) may require constant attention from the global community, and be provided in increments, others (such as vaccine development) may take on more subtle (discrete) forms, and require considerable outlays in order to ensure effective provision. Moreover, some GPGs (such as elimination of a disease) are binary in character (provision vs. failure to provide).

While recent academic disputes regarding GPGs often relate to the United Nations Development Fund (Kaul et al. 1999), the subject has been addressed in earlier studies. Kindleberger (1986), for instance, analyzed the dilemmas associated with providing transnational public goods from a realist and institutionalist perspective, while Stiglitz (1995) described international public goods according to five identified categories (global financial stability; international security; natural environment; international humanitarian aid; and knowledge). Elsewhere, Hardin (1968) placed great emphasis on collective activities at a global scale, while Russett and Sullivan (1971) explored public goods at the level of international organizations. Moreover, an important addendum to the academic discourse was put forward by Sandler through his concept of aggregation technologies and their role in GPGs provision. This concept identifies three technology types involved in GPGs creation: best shot, summation (or additive technology), and weakest link. The best-shot model describes a good produced by a contender expending maximum effort (including in terms of outlay), with a relevant example here being vaccine development. An important implication of this model is that the efforts of other contenders become insignificant, as the sole focus is on the best-shot attempt and its effects. This model is also the most demanding in terms of resources (specialist knowledge, know-how, experience). In this context, the best-shot producer is the most effective provider of public goods and is acting in the public interest. The second model – summation – refers to public goods that can be seen as the sum total of the incremental provisions provided by all involved actors (as in the case of climate protection). Lastly, the weakest-link model describes goods best provided by contenders expending minimum effort – that is, countries willing to bear the brunt of the potentially negative side-effects of such provision (e.g. drug enforcement in fragile states) (Sandler 1997, 1998, 2003). Aspects of transnational public goods provision were also analyzed in World Bank reports, though mainly in the narrow context of development aid (Kopiński, Wróblewski 2021; Ferroni 2000; Ferroni, Mody 2002; World Bank 2000). It is relevant here to note how the GPGs concept has over time departed from a microeconomics context and been incorporated into an international relations context (Kornek, Edenhofer 2020; Carbone 2007, p. 181).

While the concept of GPGs may seem intellectually appealing, its theoretical assumptions have been the subject of stringent critique. Some researchers have argued that the concept is more a political manifestation than a verifiable scientific theory (Long, Woolley 2009, p. 107), while others have claimed that the microeconomic aspects of the GPGs concept exist only to provide scientific legitimization for a theory that is in reality a loose collection of complementary ideas. In addition, it should be noted that the concept of public goods is derived from neoclassical economics (including its assumptions regarding rationality and utility maximization as being fundamental to human behavior). Many researchers exploring the subject of GPGs were, though, quick to depart from such initial assumptions, instead seeking inspiration from disciplines such as political science, sociology, and even philosophy. Another notable deficit of the GPGs concept is the perceived lack of cohesion (at least in the professional literature), which extends to such issues as to what the fundamental nature of GPGs actually is. Definitions are, for the most part, excessively broad and convoluted, raising suspicions that any type of transnational challenge can in principle be deployed as an example of GPGs (see, for example, World Bank 2007). Long and Wooley (2009) have observed that the ongoing dispute lacks analytical rigor and that the GPGs concept is merely a ‘rhetorical instrument’ (p. 107), with the debate around the concept serving primarily to elevate the significance of GPGs production rather than to explain its nature. Similar reservations are voiced by Carbone, who regards many studies on the subject as being a ‘mixture of pure economic rationality and wishful thinking’ (Carbone 2007, p. 181).

While the authors of this study are fully aware of the manifold deficits and theoretical inconsistencies attributed to the GPGs concept, the concept is nevertheless utilized here for two principal reasons. The first of these relates to the ongoing debate regarding the present and future role of the IMF in the world economy, and how its institutional structures must be adapted to modern demands and challenges. In this context, the paper explores demands for greater emphasis to be placed on international organizations (including the IMF) in GPGs production. Such a shift would serve to bolster the Fund’s legitimacy going forward, as well as offer a sanative strategy in light of the dramatic pressures on multilateral cooperation observed in recent years. The second reason is that, based on the authors’ empirical findings, it can be argued that the GPGs concept is already being explored by the IMF, despite not being adequately represented in the Fund’s internal literature and disputes.

Given that global financial stability is central to both the mission statement of the IMF’s Statute and the organization’s resultant operations, this area will form the primary focus of this study. According to the IMF’s legal mandate, it is expected to take prompt and appropriate measures to limit the incidence of financial crises, offer support in extant crises, and alleviate the effects of related financial turbulence in the national economies of IMF members. As Ferguson and others (2008) argue, financial instability disturbs investment and consumption, resulting in the rate of economic growth decreasing (or even being suppressed altogether), thereby reducing welfare in afflicted socio-economic systems. Similar conclusions are presented by Creel, Hubert and Labondance (2015), with financial instability perceived as detrimental to national economies and a barrier to economic development. Mishkin (1999), meanwhile, argues that disturbances in a financial system’s operation (i.e. conditions of financial instability) are detrimental to the effectiveness of the various aggregate economies. Thus, given the IMF’s involvement in ensuring financial stability can be considered a source of GPGs production, it is perhaps necessary to present a more exhaustive definition of what financial stability entails. Providing a conclusive definition of financial stability is, however, a challenging prospect, due to its compound character and the apparent interplay between the financial system’s various elements. In general, financial stability (or, to put it another way, a lack of financial instability) can be seen as the absence of excessive volatility, stress or crises in financial system operation. While Mishkin (1991) observes that financial stability can be framed as the absence of financial crises, Crockett (1997) argues that it represents the capacity of institutions to meet their statutory or contractual obligations, with changes in the prices of financial assets merely reflecting changes in these fundamental aspects. Elsewhere, Gadanecz and Jayaram (2008) postulate the need for ‘broader definitions of financial stability to encompass the smooth functioning of a complex nexus of relationships among financial markets, infrastructures and institutions operating within the given legal, fiscal and accounting frameworks’. Schinasi (2004), meanwhile, observes that financial stability can be thought of in terms of the financial system’s ability to:

In terms of various attempts at formulating an acceptable definition of financial stability, it may be observed that – in general – the notion is most frequently evoked in relation to ensuring the correct operation of aggregate economies’ (broadly defined) financial markets (complete with associated institutions of systemic support). Financial stability may also, however, be analyzed from a broader (transnational and global) perspective. Gulcin and Filiz (2012) note that the proliferation of financial crises (the so-called contagion effect) is nowadays much more pronounced due to the mounting complexity of multilateral financial and trade relations, including their cooperative character. Eichengreen (2004), meanwhile, argues that current financial liberalization processes also serve to increase financial instability, and so may be regarded as a potential source of crises. In this context, the notable rise in frequency (incidence) of financial crises over the past four decades should be highlighted. According to IMF reports, the period 1975–1997 saw as many as 158 episodes in which countries (both developed and developing economies) experienced substantial exchange market pressures (IMF 1998). This trend has also been confirmed in a study by Bordo and others (2001) based on the incidence of financial crises in the years 1880–1997, which shows that in general the incidence of crises ‘since 1973 has been double that of the Bretton Woods and classical gold standard periods’. This trend has continued post-1997, as evidenced by the numerous, severe and multidimensional financial breakdowns that have taken place since, including in South-East Asia (1997), Russia (1998), Brazil (1999), Argentina (2001–2002), Turkey (2001) and Uruguay (2002) (WEF, 2008), as well as, of course, the 2008–2009 global financial crisis. Further episodes of acute crisis include Russia in 2014 and Argentina in 2019. Lastly, there can be little doubt that the present COVID-19 pandemic will create a host of economic and financial crises in most affected states (IMF 2020d). The cost of pandemic regulation efforts, involving health support and financial stimulation measures (both fiscal and monetary) will inevitably result in public debt spiraling to historic highs. As such, maintaining domestic financial stability will be a serious challenge for many affected states, with potentially grave knock-on consequences for the stability of the global economy.

In view of the above, it seems safe to assert that financial stability at a transnational level can be perceived as a form of GPG. Wyplosz argues (rather perversely) that financial stability may be considered a GPG due to the fact that financial instability has already become a global public bad – that is, a universally undesirable state (or form of public good). In effect, financial crises may be seen as public anti-goods (as their ‘consumption’ is, paradoxically enough, non-rivalrous and non-exclusive). Wyplosz is apt in noting three important premises for treating financial instability as a form of global public bad. First, the consequences of financial instability are transnational, as financial markets are, in general, free of state border constraints. Second, the effects of information asymmetry – which become more acute when analyzed from a transnational perspective – mean that financial markets cannot operate optimally. Third, the moral hazard effects frequently observed in financial markets are often transnational in character (Wyplosz 1999).

Based on the definitions and arguments presented above, it may safely be assumed that the global or transnational stability of the financial sector satisfies – for the most part – the characteristics set out in the GPGs concept. For this reason, many of the available GPG classifications utilize global financial stability as a relevant example of such a good (Kaul et al. 2003; Stiglitz 1995). As Stiglitz (2006) emphasizes, everyone benefits from financial stability, while many suffer when it is lacking. Similarly, Daniel, Arce and Sandler (2002) present financial stability as an example of ‘GPGs providing benefits worldwide to developed and developing countries’. Thus, consumption of this distinctive and unique product is global in reach. In addition, it should be reiterated that financial contagion is often classified as an example of a negative external effect occurring at a transnational scale (Kanbur 2017), which potentially serves as another premise for recognizing global financial stability as a form of GPG. It should also be noted, however, that the very notion of ‘global financial stability’ within the context of the GPGs concept is, to some extent, arbitrary (as well as problematic). Global financial stability is largely the result of individual countries enjoying conditions of financial stability. Thus, global conditions are mainly shaped by activities undertaken at a national level, though transnational collective cooperation still has a major role to play in this process.

Assuming for the purpose of this analysis that global financial stability can be interpreted as a GPG, we are ultimately faced with the following key question: Who is best placed to serve as an effective provider of such a good? A popular thesis holds that intergovernmental organizations are by their nature predestined to bear the load associated with the creation and distribution of GPGs, particularly global financial stability (with the IMF held up as being potentially the leading provider of this particular product) (Joyce 2013). As Wyplosz (1999) observes, while production of financial stability on a national scale is within the competence of national or sub-national creators of macroeconomic and structural policies, intergovernmental organizations are best placed to act at suppliers of such a good at a global level. Daniel, Arce and Sandler (2002) go even further, arguing that global financial stability, as a form of a universal product – irrespective of its strong roots in national-level economic policies – is best addressed (i.e. provided more effectively) at a global level. Moreover, as observed by Kindelberger and Aliber (2005), the IMF was founded partly in response to the economic crises and bouts of financial instability seen in the 1920s and 1930s.

This paper’s exploration of the IMF’s role in GPGs provision would not be complete without proper identification of the organization’s key operational activities and their associated products. The IMF’s annual reports identify three fundamental areas of institutional activity (the ‘big three’) (IMF 2017a, 2018d, 2019a, 2020e), with the organization:

Table 1. Functions and roles of the IMF

| Economic surveillance | Lending | Capacity development |

|---|---|---|

| Bilateral surveillance | Non-concessional lending | Fiscal |

| Multilateral surveillance | Concessional lending | Monetary and financial sector |

| Policy advice | Program design | Legal |

| Data | Policy support instrument (PSI) | Statistics |

| Training |

Source: own research based on IMF data (https://www.imf.org) and official IMF annual reports (IMF, 2017a, 2018d, 2019a).

In terms of economic surveillance, the IMF monitors economic and financial policies both globally and at the level of member states’ national economies (IMF 2018c). Such activity is intended to support the international monetary system, which should in turn facilitate conditions conducive to trade and service exchange, as well as capital flows, ultimately reinforcing the fundaments of economic development. A number of significant IMF products can be identified within this area of expertise. First, through its Early Warning Exercise (EWE) model, which aims to identify potential risks (economic, financial, fiscal, and external) in the global economy, the IMF publishes (among other documents) its flagship publications: World Economic Outlook, Global Financial Stability Report, Fiscal Monitor and Regional Economic Report. Observations and conclusions from the EWE also inform the activities of the IMFs Financial Stability Board.[1] At the same time, the IMF provides a wealth of useful databases, including the World Economic Outlook Database and International Financial Statistics. Other services that can also be classified under this segment of products include the regular Financial System Stability Assessments for each member state, conducted within the framework of the Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP).

In terms of lending – i.e. financial support offered to member states suffering crisis phenomena – it should be emphasized that, in contrast to institutions dedicated purely to development aid, IMF financial support is not directed toward specific projects (IMF 2018b). Rather, it is more horizontal in character, typically taking the form of special IMF-supported programs. Financial support offered by the IMF is typically provided under one of two basic models:

It may be observed that the IMF’s current array of loan instruments is dedicated to addressing various financial disturbances and potential risks faced by individual member states, and that many of those instruments were created in direct response to the 2008–2009 global financial crisis (Wróblewski 2014).

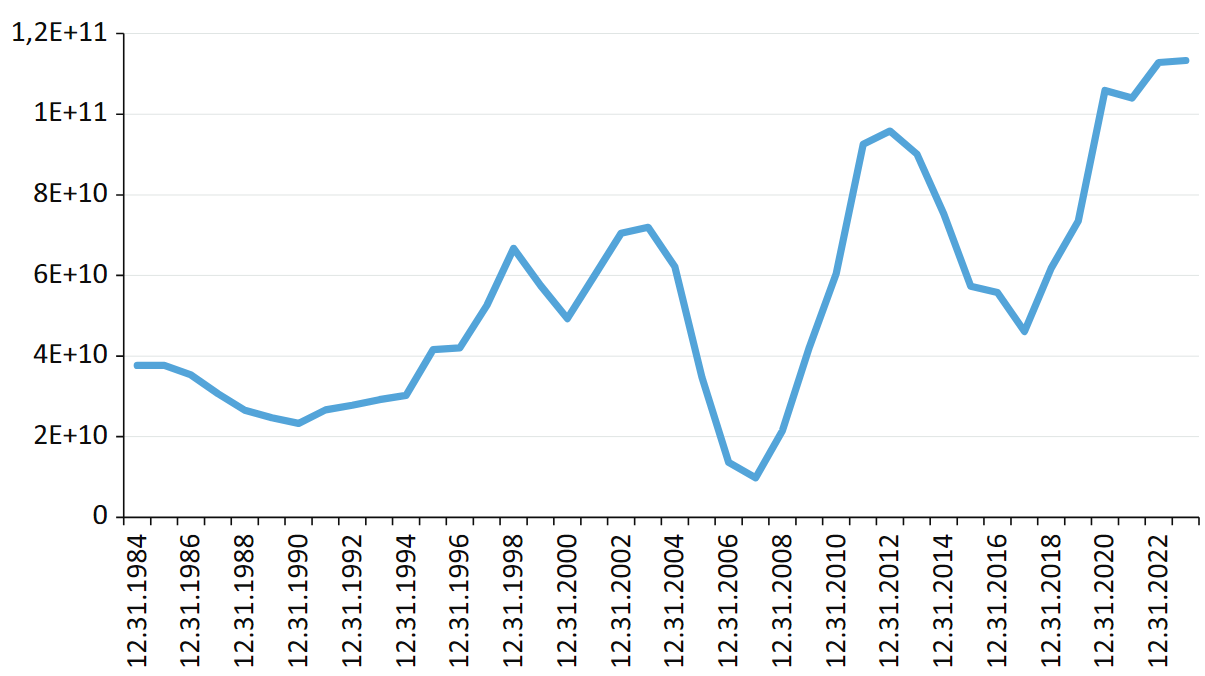

As the data presented in Figure 1 suggests, times of strong financial turbulence naturally stimulates member state demands for IMF loans. This observation is confirmed by Orastean (2014) in her study of IMF loan activities from 1953 to 2013, which finds that IMF lending support during this period was positively and strongly correlated with bouts of financial downturn. In this context, it is useful to analyze the loan activities effected by the IMF in response to the 2008–2009 global crisis, a period characterized by rapidly increasing institutional demand for financial stabilization support. This trend was also observed among several developed Eurozone counties (Greece, Ireland, Portugal), which were forced to apply for large-volume IMF loans (IMF 2017b, 2017c, 2017d). As noted by Ionescu (2014), it was in response to the crisis and its effects on global demand for such aid that the IMF significantly strengthened its lending capacity and approved a major overhaul of its lending mechanisms.

Figure 1. IMF lending activities during the period 1984–2023 (SDR)

Source: IMF (2023), Total IMF credit outstanding for all members from 1984–2023. Retrieved May 23, 2023, from https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/tad/extcred1.aspx

More recently, the global COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to a renewed surge in demand for IMF lending assets, with the first five months of 2020 seeing the Fund provide financial relief (mainly in the form of RCF and RFI) and debt relief (in the form of special grants, CCRT,[3] for the least affluent economies) to the combined tune of 17.275 billion SDR (23.608 billion USD) (IMF 2020b). During this period, the IMF registered an unprecedented number of credit applications from member states, with 102 countries submitting applications (IMF 2020c).

In terms of capacity development, this broadly defined sphere of activities aims at providing tangible technical support to IMF member states for the purpose of strengthening their systemic (fiscal, monetary, financial, legislative, statistical/reporting) capacities (IMF 2018a). The Fund also generates significant economic and financial knowledge resources, which can be employed in designing economic policies and reform strategies at a national level. Moreover, the IMF is actively involved in scientific research (and publications) associated with its areas of expertise.

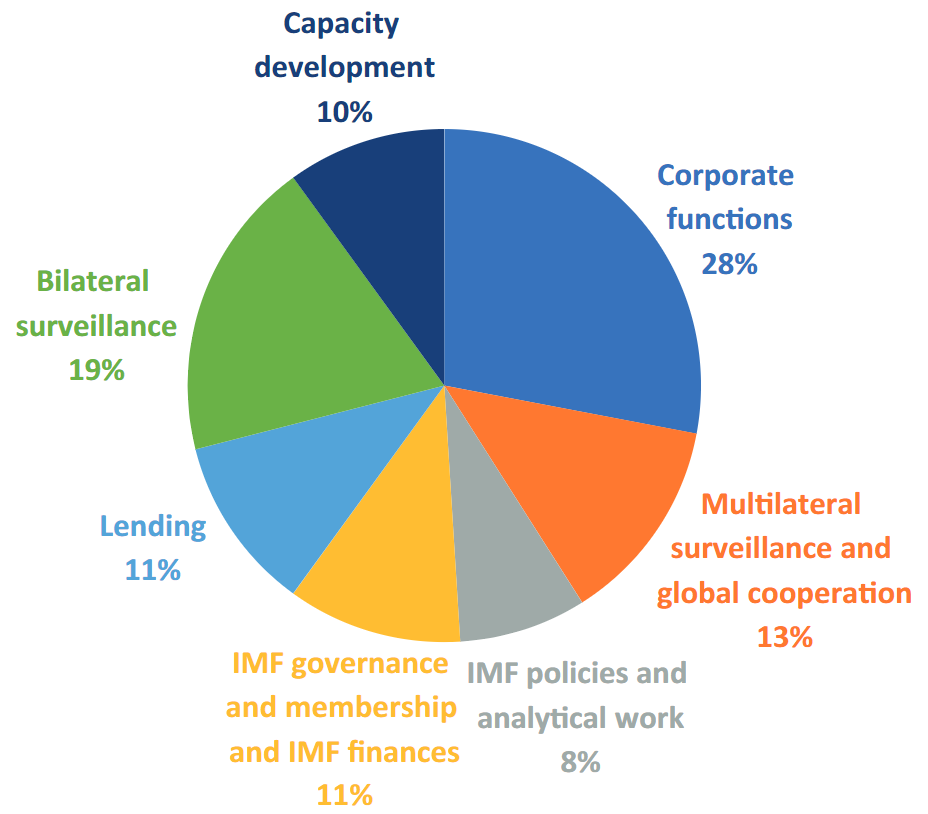

Figure 2. Structure of IMF expenses for 2022: Main categories of cost (as % of aggregate volume)

Source: own calculation based on IMF annual report (IMF 2022).

In this context, special attention should be paid to the structure of IMF expenditure in these three fundamental areas of involvement. It is worth noting that, in comparison to previous reports, the methodology has been changed. The new method of presenting data makes it difficult to precisely assign all expenses to the aforementioned categories. Nevertheless, data presented in Figure 2 suggests that, in 2022, the largest share of IMF expenditure was assigned to realizing the economic surveillance function (32%, representing aggregate outlays of bilateral and multilateral surveillance). Capacity development received an aggregate share of 10% of total expenditure (measuring only direct actions, excluding activities related to policy, analytics and other output areas). Meanwhile, the IMF’s lending activities consumed 15% of expenditure. Contrasting with previous reports, the present compilation introduces the category of “corporate functions,” which accounts for 28% of the allocated resources. Therefore, it should be assumed that a portion of the expenses previously encompassed in the three categories mentioned above, has now been incorporated into this section.

The total value of financial resources held by the IMF is currently estimated as being in the region of one trillion USD (IMF 2021a). Thus, it may be safely assumed that the Fund’s financial supply base is sizable enough to bear the burden of preventive and anti-crisis measures if such a need arises. Here, it should be highlighted that the recent increase in the IMF supply base is the result of the G20 decision taken in 2009 aimed at improving the Fund’s capacity in response to the global financial crisis. This observation alone would seem to provide an answer to the question posed in the previous section of this paper regarding who is best placed to serve as an effective provider of global financial stability as a public good.

A review of the IMF’s range of activities would seem to confirm the view that the organization’s most fundamental area of involvement remains financial stability (both at the level of individual member states and at an international/global level). As such, the Fund may be considered the most capable source of potential GPGs production in this regard. These products correspond in the main with the broadly defined category of ‘global conditions and policy outcomes’ (see Section 2), and involve the incremental provision of IMF-produced (or attempted) fundamental GPGs (i.e. global financial stability). This applies to the provision of various specific semi-products, with the final product merely the sum of such interventions. In principle, all products provided (whether directly or indirectly) by the IMF can be linked to providing global financial stability. It should be noted, however, that the relevant products offered by the IMF are not always – or even mostly – directly related to the global dimension. Moreover, the growing significance of non-financial IMF public goods production should be emphasized. As noted by Joyce and Sandler, though the Fund’s lending activities were ostensibly in decline from 2001 to 2007, the same period saw steady increases in spending on economic surveillance and capacity development, reinforcing the notion that the IMF is primarily a provider of pure public goods. For instance, money-laundering is not only undesirable in terms of its direct effects on individual national economies, but also its indirect detrimental effects on other economies. Thus, the wealth of money-laundering-related knowledge resources, procedures and preventive standards produced by the IMF and distributed among member states can be said to satisfy the characteristics of a GPG.

Joyce and Sandler (2018) also stress that IMF activity related to formulating international standards (e.g. financial reporting standards) and propagating best practice (e.g. economic policies, reducing money-laundering, collating and processing economic data) may safely be considered best-shot public goods, with the provision of such goods determined by which of the potential contributors makes the highest bid. In this context, the highest bidder is the IMF, with other (less sizable) contributions rendered largely irrelevant. According to Meltzer (2003), the IMF provides two basic forms of public goods:

Activities falling into the latter category in particular may offer tangible benefits through the increased effectiveness of financial markets at a global level. Similar views are expressed by Birdsall and Diofasi (2015), who observe that the IMF’s involvement in national performance indicators and economic surveillance of financial markets facilitates early detection of crisis risks. In effect, these activities may be viewed as elements of an ‘early warning system’ aimed at streamlining the curative measures and adjustments deployed to mitigate such risks. Edwards (2008) argues that this is the main reason behind the IMF’s recent reinforcement of its bilateral and global surveillance under Article IV, as financial turbulence in one member state can rapidly affect the operation of other economies, extending to whole regions or even the global level. Moreover, in this context, the IMF’s lending activities are generally fairly effective in terms of reducing crisis phenomena and limiting contagion. Evaluations conducted by Presbitero and Zazzaro (2012) of the Fund’s loan operations during the initial phase of the global financial crisis (2007–2010) suggest that, despite some problems (largely related to the politicization of credit decisions), the volume of such aid played a major and generally positive role in limiting crisis within the Eurozone.

It should be noted that – in line with the World Bank definition of GPGs (World Bank, 2007) – the effective supply of said goods is critically dependent on collective action undertaken at a transnational level, with the coordination of such actions realized by the IMF. Following this approach, while sub-products of this type needn’t be global in character, the final product (global financial stability) produced on the basis of such sub-products (and made accessible in a non-rivalrous and non-exclusive form) is of significance to all participants in the global economy, and may therefore be considered global in character. The essence of this interpretation rests in the observation that many sub-products provided by the IMF (such as loan support for crisis-afflicted national economies, or technical support and advisory services offered to selected economies) may, to some extent, be regarded as exclusive, given their consumption is limited to particular actors. However, if this consumption results in the systemic reinforcement of said actors, thereby avoiding crisis or limiting contagion, then the final product has in fact also been consumed by the global economy’s other actors (with the additional benefit that rivalry for such products has been culled). In the case of the IMF, it is also relevant to add that – due to the low heterogeneity of global financial stability as a product – the supply of public goods is determined by the international level of governance applicable to the context (Kapur 2002). Also relevant is the fact that, in terms of their character, many sub-products offered by the IMF are akin to pure public goods (for example, knowledge generated by the Fund is largely available to each and every actor). Thus, in general terms, it seems that the IMF (despite numerous controversies surrounding its activities) can be regarded as a provider of a variety of valuable public goods that are attractive at any level of consumption (local, regional, and global).

In light of the above, it may be assumed that the IMF is an important producer of GPGs (with regard to financial stability). Building on this insight, it can be seen that the Fund enjoys substantial comparative advantages in GPGs production compared to other relevant actors. As noted by Joyce and Sandler (2018), coordination is a key component of any GPGs production process, with the IMF boasting unmatched competence in this area (which in turn yields a wealth of comparative advantages). This once more emphasizes the IMF’s capacity to provide best-shot public goods in the arena of global financial stability. Over the past few decades, the IMF has arguably proved itself to be the most proficient and experienced international body in terms of coordinating global financial aid activities addressing financial crises and market disturbances. In many crisis episodes, the IMF was not only a lender, but the coordinator of integrated financial support packages from various sources (such as the World Bank or European Central Bank). As such, the organization has access to specific and unique know-how in terms of decision-making procedures and operating activities. In addition, as argued by Arce and Sandler (2001), individual activities often disrupt the balance (according to Nash’s definition of the equilibrium) of GPGs production, and so require effective institutional coordination. This, indeed, was the main rationale behind the creation of transnational-level institutions empowered to fulfill this role. As one senior IMF official suggests, if an organization such as the IMF hadn’t been established, it would be necessary to create one (Senior Official, IMF, interview, September 2018).

Thus, the IMF is in effect preordained (in view of the experience and resources it holds) to play the lead role as coordinator of transnational financial stabilization activities (thereby becoming the primary producer of this type of GPG). As Meltzer (2003) emphasizes, the IMF holds another important comparative advantage in the form of information access, due to its permanent working relations with the national structures and institutions of its 189 member states (granted within the procedural framework of Article 4 of the IMF Statute). Moreover, the Fund holds sizable (financial, organizational, and intellectual) resources to contain and limit financial turbulence, which – due to reforms undertaken in recent years – can be employed with relative expediency. Here, particular attention should be paid to the IMF’s experience in constructing and implementing national-level measures aimed at assisting crisis-afflicted member states. While the effectiveness of such interventions varies (and is often contested), the wealth of expertise generated through decades of such involvement constitutes an important and unique asset. It should also be reiterated that in such crisis situations, aid measures offered by the IMF have often been the only substantive support available, with financial markets tending to revert to risk-averse behavior when called upon to support countries suffering financial destabilization. Another of the IMF’s distinguishing attributes in terms of preserving global financial stability is its often indispensable role as ‘lender of last resort’. While the Fund’s involvement in this area is subject to considerable controversy due to the potential for moral-hazard-inducing effects, it remains the case that this particular role is – in the most extreme settings – imperative. As emphasized by one senior IMF official, however, a proper balance must be struck between the IMF’s involvement as lender of last resort and the risk of moral hazard (Senior Official, IMF, interview, September 2018). With that in mind, it is unequivocal in stressing another of the Fund’s key competitive advantages, namely its financial credibility and global recognition. Finally, the IMF’s involvement in scientific research and its role as a global platform for scientific cooperation should be highlighted (although these aspects of the Fund’s operation are often unspectacular and overlooked in analytical evaluations).

Eichengreen and Woods (2018) argue that, despite the many controversies surrounding the IMF, it remains an indispensable element of the global economy, serving a fundamental role as the leading provider of global financial stability. While there are several new regional initiatives – such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) or African Monetary Fund (AMF) – that may be perceived as providing competition to the IMF, their resources and, above all, history (in terms of generated knowledge and expertise) are not yet sufficient to challenge the Fund’s role. As Eichengreen and Woods (2015) point out, such projects (or designs) are typically limited to operating at a multilateral or, at most, regional level, and so are not suited to the global scale (much less solving global problems). More significantly, these organizations are already experiencing a wealth of internal problems, mostly related to governance and the adopted model of operation.

Such observations merely serve to reinforce the argument that the IMF’s capabilities – including that of GPGs producer – should be strengthened, rather than assuming that the organization is headed toward gradual marginalization or even elimination from the global institutional architecture. It is possible to observe that the IMF has no direct and immediate competition – although aid directed by governments toward other economies is a not infrequent occurrence, such support is drastically reduced in times of crises due to the extraordinary risk involved (Senior Official, IMF, interview, September 2018). This is in marked contrast to the IMF, which, when confronted by grave financial turbulence, can generally be relied upon to maintain its role as leading lender. Nissan (2015) goes even further, claiming that the Fund – in contrast to the World Bank – can be regarded as indispensable. This is evidenced by the recent global financial crisis, where IMF products (such as analyses of systemic risk in member states and its impact on financial stability at a national, regional, and global scale; and financial support for member countries most afflicted by financial turbulence) indeed proved indispensable, and the Fund itself emerged from the turmoil ostensibly stronger than it was before. Similarly, based on a broad analysis of IMF activities in the context of GPGs, Joyce (2015) suggests that the global financial crisis has served to reinforce the necessity of this form of global organization during times of grave financial downturn. Moreover, economic downturns arising due to the global COVID-19 pandemic clearly support the IMF’s unique role as guardian of global economic stabilization. According to a senior World Bank official, this is of particular importance in light of the general disillusionment felt toward the efforts of the G20, which has only served to emphasize that the world economy requires global institutional pillars (in the form of the IMF, World Bank and World Trade Organization). Paradoxically, the present crisis in multilateral cooperation may serve to stimulate collective initiatives undertaken at a transnational level, through shining a spotlight on the consequences arising from neglect of such multilateral coordination of activities (Senior Official, World Bank, interview, September 2018). Similar views are expressed by a representative of the IADB (Interview with a Senior Manager of the IADB, September 2018), who identifies failures of multilateralism during times of crisis as a potential source of systemic risk. In light of the above, bolstering the IMF’s natural comparative advantages in order to up the level of GPGs production may be required. It should be stressed, however, that the IMF’s utilization of these comparative advantages has thus far been substandard, while the efficiency of its operating activities has been decidedly limited (the Fund failed to predict the most recent global financial crisis, and IMF supported programs have often been criticized for failing to achieve their anticipated results).

Despite the lack of viable alternatives to the IMF, the fact cannot be ignored that current transformations in the global economy – particularly those associated with the geographical distribution of economic potential – constitute a critical challenge for the Fund, which, in turn, may drastically limit the organization’s GPGs production capacity. As Gallagher (2015) observes, numerous forecasts claim that at least half-a-dozen developing countries (including China, India, Brazil, Mexico, and Indonesia) will rise amid the ranks of the global economy to become leading contenders by the year 2050. Based on this, it is reasonable to assume that they will seek to develop their influence (voting power) in global governance institutions – a trend already observable in the cases of China and India. Consequently, if the IMF wishes to retain its comparative advantages, its capacity to provide products on a global scale (by making good use of these competitive advantages), and, ultimately, its legitimacy as a global actor, it will likely have to focus on modernization of its internal structures, including how electoral votes are distributed. Here, it should be noted that changes to the quota assigned to individual member states have long been mooted as part of the planned IMF structural reforms (Secretariat of the International Task Force on Global Public Goods 2004). Taking a long-term perspective, legitimation the IMF appears to be the crucial issue in the context of GPGs production capacity. As noted by one senior IMF official (Senior Official, IMF, interview, September 2018), any grounds that could be used to suggest the IMF is an organization serving only a narrow group of recipients would have the effect of depleting its GPGs production capacity. Reforms are thus vital, despite the process being fraught with political challenges and subject to contestation by many IMF member states (particularly those that would stand to lose in terms of reduced voting powers). Regardless of the measures already adopted in this sphere, the IMF continues to struggle with the problem of developing countries having inadequate representation in its formal proceedings and decision-making procedures. As emphasized by Desai and Vreeland (2011), this has led to the Fund’s credibility in many regions of the world being eroded, which has had the additional effect of boosting local initiatives and other forms of direct competition. The proposed quota redistribution – which has received strong support from prominent developing economy actors – may thus prove effective in limiting such negative trends, while at the same time building a sense of shared responsibility among member states regarding GPGs production.

The IMF’s operations as a provider of financial stability-related GPGs is also burdened by other limitations. Obsfeld and Taylor (2017) argue that, despite the implementation of more flexible lending instruments, the IMF still faces the so-called ‘stigma’ problem – that is, the perceived stigma associated with the Fund’s support. In other words, aid recipients are, to an extent, branded as potential sufferers of serious disturbance. As such, member states tend to regard IMF support as a ‘last-ditch resort’, and are generally reluctant to proceed with their applications, which in term impedes how the Fund can respond to potential or real threats. Thus, the lending instrument reforms introduced by the Fund in response to the most recent global financial crisis – while much needed – failed to address many of the key structural problems negatively impacting the organization’s operation. Moreover, IMF products are not sufficient to ensure perpetual stability, meaning further crisis episodes are unavoidable. This may be regarded as evidence of the IMF having ‘innate’ limitations when it comes to fulfilling its role as provider of financial-stability-related GPGs. Such limitations are directly relatable to the Fund’s structure (for the most part, the IMF has only limited influence on economic and financial policies implemented by individual member states).

Woods (2006) argues that operation of the IMF (as well as the World Bank) is largely determined by the preferences of its most influential member states, by internal bureaucratic constraints, and by the internal policies of individual recipients of support. As Ötker-Robe (2014) observes, however, these limitations can also be viewed in a broader context – one in which the institutional architecture designed to contain global risks no longer corresponds with the current scale of transnational networking and integration trends. In effect, the international community (in a sense, the main provider of GPGs and facilitator of collective activity at a transnational level) no longer has the capability to adequately supply GPGs (even through international bodies). Possible reasons for this include inadequate resources (both material and immaterial); the scale and complexity of problems; and the wide discrepancies between various national interests and strategic priorities. As such, the IMF – as a key element of the current regime of international cooperation – can be seen to reflect the multitude of contradictions and conflicts apparent in this sphere. A senior IMF official (Senior Official, IMF, interview, September 2018) complements this by claiming that member states often exert strong political resistance to broad international cooperation (and, consequently, GPGs production). A senior World Bank official (Senior Official, World Bank, interview, September 2018), meanwhile, argues that the initial design of the IMF’s (and World Bank’s) structures has drastically limited its capacity to produce GPGs, as each stakeholder (individual member states) strives to maximize their own membership benefits. Consequently, global approaches to problems are often marginalized at the expense of the pragmatic interests and needs of individual member states (which becomes the approach often followed by country directors). Hence, in a context of widespread skepticism regarding multilateralism, the structural determinants of the IMF and World Bank act as impediments to the practical realization of their mandates (including GPGs production) (interview with a Senior Research Manager, World Bank, September 2018). Given current political and economic conditions, this ultimately leads to the conclusion that intergovernmental institutions would profit from revisiting their sense of mission.

It should be noted that even the discourse within the IMF itself tends to be fairly vague and non-committal regarding GPGs production. On the one hand, as observed by a senior IMF official (Senior Official, IMF, interview, September 2018), IMF staff – particularly its economists – do display some awareness of the GPGs concept (as a sort of ‘latent element of the Fund’s DNA’). On the other hand, GPGs issues are not adequately discussed in formal documents, and even when they are, their articulation is rarely explicit. As a senior IMF official (interview with an executive director at IMF, interview, September 2018) asserts, direct expressions of the GPGs concept are sporadic and exceptional. Here, it should be added that in its 2019 financial surveillance report, the IEO explicitly states that the ‘FSAP would seem to be a fully-justified global public good’ (IEO 2019b). However, another IEO report from the same year references the GPGs idea only indirectly, where it states that support for ‘fragile states’ provides support for the entire global economy (IEO 2019a). Moreover, the IMF conducts no quantitative evaluations on any of its activities or policies that satisfy the definition of GPGs production. Instead, the internal debate is mainly focused on ‘standard’ issues related the budgetary requirements (in terms of member state contributions) of realizing the organization’s statutory functions. In addition, there would be difficulties in persuading member states to approve an increase in the IMF’s financial base, particularly in light of disputes over the ‘traditional’ model of multilateral cooperation observed in recent times, particularly in the US. The GPGs perspective is also not properly reflected in the structure of the IMF’s governance, which means it is relegated to the periphery of the Fund’s active involvement. While fuller realization of the concept is theoretically possible within the IMF forum, this would almost certainly require some sort of ideological transformation in the general approach of individual member states. Relevant to this point is the process seen in the recent appointment of the new director of the IMF following Christine Lagarde’s resignation in 2019. The previous practice had been for nominees to come from Europe (whereas Americans were nominated for the directorship of the World Bank). This time, however, three of the six candidates represented other regions of the world. In the end, the post was given to a European representative – Kristalina Georgieva of Bulgaria – which can be seen not only as an attempt to uphold established practice, but as a deeper indicator of the general lack of enthusiasm for substantive change in the IMF’s established model of operation.

Despite the many problems of the multilateral model of cooperation, emerging challenges will continue to stimulate demand for GPGs in the global economy, including products created by the IMF. The Fund’s ability to provide diversified financial stability products (particularly at the global level) means it is a good fit for the GPGs concept (especially as a supplier of best-shot public goods). Here, it is necessary to accept the basic assumption that international financial stability should be recognized as a GPG (which is supported by a number of important arguments). At the same time, given the potential theoretical and methodological doubts arising from this (at least with regard to some IMF products), it must be taken into account that the Fund’s production of GPGs has, to a certain extent, a contractual nature. The GPGs concept is, as it seems, most fully revealed in the case of IMF-produced knowledge and its associated products (international standards, databases, education), which can arguably be viewed as pure public goods. Moreover, IMF activities related to multilateral financial surveillance can be considered an important example of GPGs. While the Fund’s remaining products (including lending activity, technical assistance, and monitoring of individual countries) cannot unambiguously be designated GPGs, as they target specific beneficiaries, they may at the same time constitute components of global financial stability.

The IMF undoubtedly has the potential (and resources) to produce GPGs. This could offer the Fund a strong source of long-term legitimacy, and, as such, Meltzer (2003) recommends that the organization focuses on prevention and crisis support activities. Compared to other (multilateral or regional) intergovernmental organizations, the IMF has several significant comparative advantages (including high financial credibility, a globally recognizable brand, financial resources, experience, and staff) that predispose it toward playing a greater role in GPGs production. Even so, the model governing the functioning of the IMF contains a number of limitations that reduce the organization’s GPGs-producing ability (e.g. issues with maintaining global legitimacy and quota division ‘stiffness’; the ‘stigma’ problem; bureaucratic procedures; limited influence on member states’ policies; being rooted in the politics of the most influential Western countries; acting according to a logic that maximizes benefits for particular member states). Moreover, GPGs as an explicit concept has thus far appeared only sporadically in the IMF’s work and activities. Meanwhile, at the political level, it is not always possible to reach consensus regarding IMF activities aimed at intensifying international cooperation. Villafranca (2014) states that further reform of the Bretton Woods institutions is necessary, and in the case of the IMF, such changes should be directly linked to GPGs production. At the same time, he postulates that the impact on the institution should depend on the participation of a given member state in the production of GPGs.

Increasing the IMF’s GPGs-production capacity would require consensus on the institution’s future role in the global economy, with the world’s leading economies (i.e. the G20, and above all the US) developing a new vision for cooperation within international organizations. The creation of a new multilateralism has been mentioned with growing frequency in both the academic and political discourse. Gallagher and Kozul-Wright suggest that any new rules on international cooperation should lead to a broader and more balanced distribution of globalization’s benefits, and that within the multilateral system countries should have a common – albeit differentiated – responsibility for GPGs production. Meanwhile, global governance institutions should serve all their stakeholders, which means a variety of opinions and needs must be accommodated (Gallagher, Kozul-Wright 2019). In this context, it is significant that the IMF (as personified by its former managing directors, David Lipton and Christine Lagarde) has emphasized the need for a new multilateralism oriented toward a wider and more sustainable distribution of globalization’s positive effects, with governments and institutions working together for the common good (Lipton 2018).

In addition, further significant changes to the IMF’s operational activities are required. Reinhart and Trebesch (2016) note that, despite the Fund introducing a number of new instruments that resemble central bank tools (RCF or FCL) during the recent global financial crisis, the need to strengthen the organization’s ability to act as lender of last resort remains. At the same time, it is important that the IMF does not simply focus on loans to the lowest-income or most indebted countries, pushing it toward becoming a development agency. Rather, the Fund’s unique basis should be its provision/maintenance of financial sector liquidity in member states in response to short-term balance of payments problems. Here, it should be noted that the G20 Eminent Persons Group on Global Financial Governance (EPG) initiative, launched in April 2017, developed a comprehensive set of reform recommendations for the Bretton Woods institutions. The EPG, among others, recognizes the need for the IMF to evolve with a view to ensuring member countries can benefit from global capital flows while maintaining global financial stability. Hence, the IMF should have both permanent and emergency resources deployable in response to countries’ temporary liquidity needs, thereby allowing the organization to take effective action in the face of global financial turbulence and counter the contagion effect, acting as ‘lender of last resort’ if necessary. The EPG also notes that international financial institutions (including the IMF) play a unique and globally important role within the international community, providing it with public goods in the form of analyses and data that are crucial to countering global threats and strengthening sustainable development (EPG 2018). The international community needs effective institutions capable of reacting on a global scale (and thus producing GPGs). Continuation of the IMF reform process would therefore appear to be a key condition for the organization’s continued relevance in the face of emerging global threats.

Arce D., Sandler T. (2008), Transnational public goods: Strategies and institutions. “European Journal of Political Economy”, 17(3): 493–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0176-2680(01)00042-8

Barrett S. (2006), Critical factors for providing transnational public goods. In Expert Paper Series Seven: Cross-Cutting Issues, Secretariat of the International Task Force on Global Public Goods.

Barrett S., Dannenberg A. (2022), The Decision to Link Trade Agreements to the Supply of Global Public Goods, “Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists”, 9(2): 273–305. https://doi.org/10.1086/716902

Beazer Q.H., Woo B. (2016), IMF conditionality, government partisanship, and the progress of economic reforms, “American Journal of Political Science”, 60(2): 304–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12200

Bird G. (2001), IMF programs: Do they work? Can they be made to work better? “World Development”, 29(11). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00077-8

Birdsall N., Diofasi A. (2015) Global public goods for development: How much and what for, Center for Global Development.

Boorman J. (2008), An Agenda for reform of the International Monetary Fund, Occasional Paper 38. Fredris Ebert Stiftung.

Bordo M.D., Eichengreen B., Klingebiel D., Soledad Martinez-Peria M. (2001), Is crisis problem growing more severe? “Economic Policy,” 16(32). https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0327.00070

Buchanan J. (1968), The demand and supply of public goods, Rand McNally.

Buchholz W., Sandler T. (2021), Global Public Goods: A Survey, “Journal of Economic Literature”, 59(2): 488–545. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20191546

Buira A. (Ed.), (2005), Reforming the governance of the IMF and the World Bank, Anthem Press.

Carbone M. (2007), Supporting or resisting global public goods? The policy dimension of a contested concept, “Global Governance”, 13(12). https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-01302004

Cornes R., Sandler T. (1986), The theory of externalities, public goods and club goods, Cambridge University Press.

Cornes R., Sandler T. (1994), Are public goods myths?, “Journal of Theoretical Politics”, 6(3): 369–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951692894006003006

Cowen T. (1985), Public goods definitions and their institutional context: A critique of public goods theory, “Review of Social Economy”, 43(1): 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346768500000020

Creel J., Hubert P., Labondance F. (2015), Financial stability and economic performance, “Economic Modelling”, 48(C): 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2014.10.025

Crockett A. (1997), Why is financial stability a goal of public policy? In Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City (Ed.), Managing financial stability in a global economy, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Daniel G., Arce M., Sandler T. (2002), Regional public goods: Typologies, provision, financing, and development assistance, EDGI.

Desai R.M., Vreeland J.R. (2001), Global governance in a multipolar world: The case for regional monetary funds, “International Studies Review”, 13(1): 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2486.2010.01002.x

Edwards R.W. (2008), Policy and statistical issues underpinning financial stability: The IMF perspective. In OECD, Statistics, knowledge and policy 2007: Measuring and fostering the progress of societies.

Eichengreen B. (2004), Financial instability. In B. Lomborg (Ed.), Global Crises, Global Solutions (pp. 251–300), Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511492624.006

Eichengreen B., Woods N. (2015), The IMF’s unmet challenges, “The Journal of Economic Perspectives”, 30(1): 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.1.29

EPG (2018), Making the global financial system work for all: Report of the G20 Eminent Persons Group on global financial governance.

Eurodad (2006), Eurodad Report: World Bank and IMF conditionality: a development injustice.

European Central Bank (n.d.), Financial stability and macroprudential policy. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/ecb/tasks/stability/html/index.en.html (accessed: 17.04.2018).

Feldstein M. (1998), Refocusing the IMF, “Foreign Affairs”, 77(2). https://doi.org/10.2307/20048786

Ferguson W., Hartmann P., Panetta F., Portes R., Laster D. (2008), International financial stability, Geneva Reports on the World Economy 9. International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies (ICMB).

Ferroni, M. (2000). Reforming foreign aid: The role of international public goods. Operations Evaluation Department (OED) Working Paper Series No. 1.

Ferroni M., Mody A. (2002), International public goods: Incentives, measurement, and financing, World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0979-0

Gadanecz B., Jayaram K. (2008), Measures of financial stability: A review. In Measuring financial innovation and its impact: Proceedings of the IFC Conference, Basel 26–27 August 2008, IFC Bulletin No. 31. Bank of International Settlements.

Gallagher K.P. (2015), Ruling capital: Emerging markets and the reregulation of cross-border finance, Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/cornell/9780801453113.001.0001

Gallagher K.P., Kozul-Wright R. (2019). A new multilateralism: Geneva principles for a global green new deal, UNCTAD and Global Development Policy Center, Boston University.

Gulcin O.F., Filiz U.D. (2012), Global financial crisis, financial contagion, and emerging markets, IMF Working Paper WP/12/293. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781475551167.001

Hardin G. (1968), The tragedy of the commons, “Science”, 162(3859): 1243–1248. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

IEO (2013), Evaluation report: The role of the IMF as trusted advisor.

IEO (2014a), Evaluation report: Recurring issues from a decade of evaluation: Lessons for the IMF. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781498343237.007

IEO (2014b), Evaluation report: IMF response to the financial and economic crisis. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781498342643.007

IEO (2016), Evaluation report: The IMF and the crises in Greece, Ireland, and Portugal.

IEO (2019a), Evaluation report: The IMF and fragile states.

IEO (2019b), Evaluation report: IMF financial surveillance.

IMF (1998), Financial crises: Characteristics of vulnerability. In World economic outlook 1998.

IMF (2017a), Annual Report 2017: Promoting inclusive growth.

IMF (2017b), Greece: Financial position in the Fund as of February 28, 2017.

IMF (2017c), Ireland: Financial position in the Fund as of February 28, 2017.

IMF (2017d), Portugal: Financial position in the Fund as of February 28, 2017.

IMF (2018a), IMF capacity development. Retrieved April 15, 2018, from https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/imf-capacity-development

IMF (2018b), IMF lending. Retrieved April 15, 2018, from https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/IMF-Lending

IMF (2018c), IMF surveillance. Retrieved April 15, 2018, from https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/IMF-Surveillance

IMF (2018d), Annual report 2018: Building a shared future.

IMF (2020a, April 15), Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT). Retrieved April 15, 2020, from https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2016/08/01/16/49/Catastrophe-Containment-and-Relief-Trust

IMF (2020b), Emergency financing and debt relief, Retrieved June 10, 2020, from https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/COVID-Lending-Tracker

IMF (2020c), The IMF’s response to COVID-19. Retrieved June 10, 2020, from https://www.imf.org/en/About/FAQ/imf-response-to-covid-19

IMF (2020d), World economic outlook update: A crisis like no other, an uncertain recovery.

IMF (2021), Total IMF credit outstanding for all members from 1984–2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021, from https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/tad/extcred1.aspx

IMF (2021a, March 3), The IMF at a glance. Retrieved August 20, 2021, from https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/IMF-at-a-Glance

IMF (2022), Annual raport 2022. Crisis upon crisis

IMF (2023), Total IMF credit outstanding for all members from 1984–2023. Retrieved May 23, 2023, from https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/tad/extcred1.aspx

Ionescu A. (2014), The functionality of IMF programs in economics, “Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences”, 116(21): 4135–4139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.904

Jensen N.M. (2004), Crisis, conditions, and capital: The effect of International Monetary Fund agreements on foreign direct investment inflows, “The Journal of Conflict Resolution”, 48(2): 194–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002703262860

Joyce J.P. (2013). The IMF and global financial crises: Phoenix rising?. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139029735

Joyce J.P., Sandler T. (2018), IMF retrospective and prospective: A public goods viewpoint, “The Review of International Organization”, 3(3): 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-007-9029-7

Kanbur R. (2017), What is the World Bank good for? Global public goods and global institutions, CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP12090.

Kanbur R., Sandler T., Morrison K. (1999), The future of development assistance: Common pools and international public goods, Policy Essay No. 25. Overseas Development Council.

Kapur D. (2002), The common pool dilemma of global public goods: Lessons from the World Bank’s net income and reserves, “World Development”, 30(3): 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00120-6

Kaul I., Conceicao P., Le Goulven K., Mendoza R. (Eds.), (2003), Providing global public goods: Managing globalization, UNDP. https://doi.org/10.1093/0195157400.001.0001

Kaul I., Grubnerg I., Stern M.A. (Eds.), (1999), Global public goods: International cooperation in the 21st century, Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0195130529.001.0001

Kindleberger C.P. (1986). International public good without international government, “American Economic Review”, 76(1): 1–13.

Kindleberger P., Aliber R.Z. (2005), Manias, panics and crashes: A history of financial crises, 5th edition. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230628045

Kopiński D., Wróblewski M. (2021), Reimagining the World Bank: Global Public Goods in an Age of Crisis, “World Affairs”, 184(2): 151–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/00438200211013486

Kornek U., Edenhofer O. (2020), The strategic dimension of financing global public goods, “European Economic Review”, vol. 127.

Lane T., Philips S. (2002), Moral hazard: Does IMF financing encourage imprudence by borrowers and lenders? IMF Economic Issues No. 28. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781589060883.051

Lipton D. (2018, December 11), Why a new multilateralism now? https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2018/12/10/sp121118-why-a-new-multilateralism-now

Long D., Woolley F. (2009), Global public goods, critique of an UN discourse, “Global Governance”, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-01501007

Lorenzo F., Noya N. (2006), IMF policies for financial crises prevention in emerging markets, UNCTAD, G-24 Discussion Paper Series No. 41.

Meltzer A. (2003), What future for the IMF and the World Bank? Quarterly International Economics Report, Carnegie Mellon Gailliot Center for Public Policy.

Meltzer A., Bergsten F., Calomiris C., Campbell T., Feulner E., Hoskins W., Huber R., Levinson J., Sachs J., Torres E. (2000), Results and recommendation of the International Financial Institutions Advisory Commission: Final report to the U.S. Congress and Department of Treasury.

Mishkin F.S. (1991), Anatomy of a financial crisis, NBER Working Paper No. 3934. https://doi.org/10.3386/w3934

Mishkin F.S. (1999), Global financial instability: Framework, events, issues, “Journal of Economic Perspectives”, 13(4): 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.13.4.3

Musgrave R. (1959), The theory of public finance: A study in public economy, McGraw-Hill. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-23426-4

Musgrave R., Musgrave P.B. (2003), Prologue in advancing the concept of public goods. In Kaul I., Conceicao P., Le Goulven K., Mendoza R. (Eds.), Providing global public goods. Managing globalization, Oxford University Press.

Nissan S. (2015, May 11), As obituaries are written for the World Bank, the IMF is set to become indispensable, “Financial Times”, Opinion: beyondbrics.

Obstfeld M., Taylor A.M. (2017), International monetary relations: Taking finance seriously, “The Journal of Economic Perspectives”, 31(3): 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.3.3

Orastean R. (2014), The IMF lending activity: A survey. “Procedia Economics and Finance”, 16: 410–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00820-X

Ötker-Robe I. (2014), Global risks and collective action failures: What can the international community do? IMF Working Paper WP/14/195. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781498396554.001

Paloni A., Zanardi M. (Eds.), (2006), The IMF, World Bank and policy reform, Routledge.

Presbitero A.F., Zazzaro A. (2012), IMF lending in times of crisis: Political influences and crisis prevention, “World Development”, 40(10): 1944–1969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.04.009

Radlett S., Sachs J. (1998), The East Asian financial crisis: Diagnosis, remedies, prospects, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity No. 28. https://doi.org/10.2307/2534670

Reinhart C.M., Trebesch C. (2016), The International Monetary Fund: 70 years of reinvention, “The Journal of Economic Perspectives”, 30(1): 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.1.3

Russett B.M., Sullivan J.D. (1971), Collective goods and international organization, “International Organization”, 25(4): 845–865. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300017768

Samuelson R. (1954), The pure theory of public expenditure, “The Review of Economics and Statistics”, 36. https://doi.org/10.2307/1925895

Sandler T. (1997), Global challenges: An approach to environmental, political, and economic problems, Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139174886

Sandler T. (1998), Global and regional public goods: A prognosis for collective action, “Fiscal Studies”, 19(3): 221–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5890.1998.tb00286.x

Sandler T. (2003), Assessing the optimal provision of public goods: In search of the Holy Grail. In Kaul I., Conceicao P., Le Goulven K., Mendoza R. (Eds.), Providing global public goods. Managing globalization, Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0195157400.003.0006

Schinasi G.J. (2004), Defining financial stability, IMF Working Paper WP/04/187. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781451859546.001

Secretariat of the International Task Force on Global Public Goods (2004), Meeting global challenges: International cooperation in the national interest: Towards an action plan for increasing the provision and impact of global public goods.

Smith R., Beaglehole R., Woodward D., Drager N. (2003), Global public goods for health: Health economic and public health perspectives, Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198525448.001.0001

Stiglitz J. (1995), The theory of international public goods and the architecture of international organisations, United Nations Background Paper No. 7. Department for Economic and Social Information and Policy Analysis.

Stiglitz J. (2002), Globalization and its discontents, Penguin Books.