https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2223-6172

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2223-6172

Territorial shifts after World War II entailed critical demographic changes: Germans were expelled from Elbing; Poles from the eastern territories were supposed to take their place in Elbląg. Personal and national narratives had to be created from scratch. The article explores different forms of texts and maps – memoirs, tourist guides, literature, and an exhibition – to scrutinise different city and neighbourhood narratives from German and Polish standpoints. Besides analysing the central motifs and narrative strategies that rely on an urban visualisation of memory, it rejects the popular notion of a palimpsest in favour of a decolonial perspective on urban space. Proposing a way to imagine a city beyond nation-based concepts can stimulate reconsidering hierarchic city structures.

Keywords

Western Territories, resettlement, German-Polish relations, urban history, mental maps

Zmiany terytorialne po II wojnie światowej pociągnęły za sobą istotne zmiany demograficzne: w Elblągu wysiedlono Niemców, a osiedlono Polaków z dawnych ziem wschodnich. Nie tylko narodowa, ale i prywatna historia musiała być tworzona od podstaw. Poprzez badanie różnych rodzajów tekstów i map (wspomnienia, przewodniki turystyczne, literatura, wystawy), w artykule przeanalizowano rozbieżne narracje o mieście i sąsiedztwie z niemieckiej i polskiej perspektywy. Oprócz analizy głównych motywów i strategii narracyjnych, które opierają się na miejskiej wizualizacji pamięci, artykuł kwestionuje popularne pojęcie palimpsestu na rzecz dekolonialnej perspektywy przestrzeni miejskiej. Odpowiedź na pytanie o to, jak wyobrazić sobie miasto poza koncepcjami narodowymi, może stymulować ponowne rozważania na temat hierarchicznych struktur miast.

Słowa kluczowe

Ziemie Zachodnie, przesiedlenia, polsko-niemieckie relacje, historia miejska, mapy mentalne

Moja ulica murem podzielona

Świeci neonami prawa strona

Lewa strona cała wygaszona

Zza zasłony obserwuję obie strony

Lewa strona nigdy się nie budzi

Prawa strona nigdy nie zasypia

My street divided by a wall

The right side glows with neon lights

The left side all extinguished

From behind the curtain I watch both sides

The left side never wakes up

The right side never falls asleep[1]

The book Poniemieckie [Post-German] by Karolina Kuszyk (2019) inspired me to start my article by quoting a 1988 song by the famous Polish band Kult. It addresses the partition of the city of Berlin and the schizophrenia of two worlds on either side of the wall, whose unification seems impossible. The contrast of one side blossoming and the other fading, the clash of two worlds, can be a metaphor for the first months and years of Polish and German coexistence in the cities ceded to Poland after World War II. In her book, Kuszyk links the song and the urban fabric – the houses once inhabited by Germans – with the diverging perceptions of towns that underwent a complete population exchange as the houses of expelled Germans were appropriated by Poles resettled from the East. In 1989, locals and scholars began investigating the multicultural heritage of these towns, acknowledging their evolving identities.

Research on Central European countries made ‘palimpsest’ a buzzword in the study of urban space that focused on literature[2] (particularly that by the “Gdańsk School” of writers[3]), photography,[4] urban and heritage studies,[5] and historiography.[6]

A palimpsest is “a parchment or other writing material written upon twice, the original writing having been erased or rubbed out to make place for the second; a manuscript in which a later writing is written over an effaced earlier writing”.[7] The palimpsest concept seems appropriate because it implies simultaneousness. However, it stresses a hierarchy in the creative process: Whatever makes itself visible decides the degree to which earlier traces remain visible, are reconfigured – or silenced.

This landscape multimodality also includes affect (Wee & Goh, 2020) with the correlating range of emotions and sentiments that the cultural bearing of the landscape evokes and nurtures through memories, narratives, images and ideologies. The ideological investment of cultural landscape has been recognised in studies on nation(alism) and how it links identity with territory.[8]

Territorial shifts after World War II entailed political decisions from ‘above’ based on a binary worldview. How can someone conceive of a city or town without the confines of ideology or national identity?

This article[9] analyses the development of divergent city and neighbourhood narratives and rejects the popular notion of a palimpsest in favour of a decolonised perspective on urban space. In particular, I explore both German and Polish metaphors linked to the city. Starting with textual (press clippings, autobiographic literature, memoirs) and cartographic sources, I end by opposing the divergent and often contradictory imageries with a museum exhibition that seeks to overcome the connection between the identity of place and territorial claims. Early postwar memoirs emphasise the difficulties of surviving mentally and practically in a contested land whose future seemed insecure. However, the exhibition Elbląg reconditus attempts to rewrite urban history and neighbourhood issues as seen by the town itself. I argue that this post-national approach revises the popular palimpsest notion and the hierarchies in its discourses. Over time, the palimpsest narrative developed from an impossible cohabitation of Poles and Germans into acknowledging the cultural potential of a city with a multinational heritage. Turning the narrative power from individuals to the city opens another perspective on the city as the narrator, a character whose plot (i.e. its history) follows patterns identified by Jonathan Philips.[10] I apply a broader understanding of texts using the cultural studies’ concept of cultural scripts with semiotic and semantic structures to decode.[11] Memoirs, media, and maps apply different methods to convey narratives. By analysing different methods and metaphors, I wish to bring together literature and urban studies, both of which evoke mental maps since there is a mutuality of texts, space, and mental mapping: “For spatial narratives, places, as well as people, can be treated as characters, enabling critical juxtaposition of different places which serve as an example for broader geographic patterns”.[12]

Severely destroyed in World War II, Elbląg became part of Poland due to the border shift that pushed Poland westward in 1945. Elbing, as the Hanseatic city was called in German, had been an important trade and industrial hub. A strategically significant site for producing war supplies, it became a site of forced labour during the war and, in 1940, that of a subdivision of the Stutthof concentration camp.[13] When the Red Army arrived in January 1945, Elbląg was plundered, destroyed, “and set on fire out of hatred and the claim for revenge”.[14] According to Maria Lubucka-Hoffmann, who leads Elbląg’s contemporary urban planning, the fact that these ‘enemy’ territories had been promised to Poland made no difference:[15] The Red Army reduced 98 per cent of the old town to rubble and ash.[16]

The immediate postwar period was characterised by both Polish and German demands for the territory. The ubiquitous lack of building materials, housing options, and basic infrastructure made it particularly challenging for new arrivals to regard their new living place as ‘home’.[17] The first settlers, mainly from the Bug and Vilnius regions, left after just a few days because they were scared off by the “massive destruction, lack of jobs, flooded Żulawy [the delta area of the Vistula river – E.-M. H.] and the temporariness of political solutions”.[18] The socialist parole was bent on incorporating the new western territories into the “new socialist culture based on national traditions”.[19] At the same time, German politicians and associations called for “returning the East German territories to German governance”.[20] Claims about “the German East” only fell silent after the Warsaw Treaty of 1970.

German newspapers and magazines frequently wrote about lost western Polish cities before the Warsaw Treaty was signed. At first, it was described as a major concern for the general public. In the 1960s, German right-wing parties adopted the issue before it was critically examined by the 1968 student movement that challenged the German perpetrators’ responsibility.[21] It was mainly the Soviet Army and the Polish administration around which the discussions of the Germans’ expulsion were centred[22] – thereby influencing how West German media treated the USSR and Poland.

An analysis of press clippings[23] reveals that German texts have usually avoided stating why the city was reduced to rubble in 1945. Suppressing Germany’s defeat and the Russian aggression in statements like “War events drastically changed the cityscape in 1945”,[24] newspapers effectively highlight only the positive aspects of Germany’s heritage.

Elbing […] the city of Hermann Balk[25] and the Teutonic Order. Narrow, high burgher houses like the ones in Rothenburg and Dinkelsbühl lined Sperling and Kettenbrunnen Streets. The musical architecture of the delicate facades curved upward to the fourth and fifth floors, where stepped gables flirted with funny curlicues.[26]

This quote creates an image of harmony and grace fused with Elbing’s political and cultural influences. The livability of old Elbing is evoked by emphasising the once-German city’s worth, comparing it to Rothenburg and Dinkelsbühl on Bavaria’s “Romantic Route”. Travel agents had established that theme route linking unique medieval towns and picturesque castles said to be especially representative of Germany’s culture and landscape in the 1950s.[27] Drawing a connection between these cities reflected the need to incorporate the former German territories into the West German imagination to make those unfamiliar with them or unaffected by expulsion recognise their importance. Cultural historians Eva and Hans Henning Hahn argue that the way newspapers prioritised the topic often clashed with the views of Germans who did not experience resettlement and considered it a minor issue.[28]

This article, as well as many others, humanised the city, pointing out the catastrophic harm to Elbing that caused its ‘death’[29] and deprived it of “any sign of life”.[30] German authors usually considered the new inhabitants and Polish authorities as incapable of reviving the town that had once been prosperous due to its shipbuilding and engineering industries.[31] The Göttinger Arbeitskreis, a research association of persons displaced from the former German territories, continue to anthropomorphise them and demand their return. The ‘festering wound of Europe’[32] could only be healed by Germans returning with their agricultural and management talent to “make the country blossom”.[33] Provisional buildings and uncivilised living standards were also common in the German imaginary: Not only did most articles neglect the history and the Polish settlers’ precarious housing situation,[34] but Polish people were depicted as unskilled. One reporter stated: “I was told that the present inhabitants, who come mainly from Galicia and Ukraine, often keep their livestock in the cellars of the big houses”.[35] This ‘backwardness’ was reinforced by reports of Poles’ high alcohol consumption that was said to result from the unfavourable position of the “country between the two frontiers”.[36] This view of Polish people as passive objects deprived of national agency supports the image of inferior people ‘always torn’ between the great powers, whose only relief was alcohol. This might be one reason why German authors usually considered the new inhabitants incapable of reviving the town: The motif of drug and alcohol abuse, with Poland defined as a society vegetating at the margins,[37] fits into the German narrative of a sickly space that legitimised discriminatory policies.[38]

The authors of the study Wzorce konsumpcji alkoholu [Patterns of Alcohol Consumption] point out how alcohol is used as a strategic and ideological tool to control a society.

Alcohol became a tool in Hitler’s policy of exterminating the Polish nation. As Kazimierz Moczarski emphasised in Conversations with an Executioner, “The goal of this policy was to bring about widespread alcohol sickness, the mental and biological decay of the nation”. […] The chaotic postwar reality involved a mix of traditionally rural and urban patterns of alcohol consumption. One cumulative model emerged: a combination of rural drinking – in frequent but ‘binge’ drinking – and the old urban pattern of drinking frequently, but in smaller quantities. The new model combined the worst of both: large quantities, frequently consumed.[39]

Germans viewed Polish passivity, poor health, and the lack of intelligent city planning as putting the city at the mercy of the forces of nature. The city was perceived as a living organism that needed to be maintained: “Life has withdrawn […] Building material came from the ruins of the old town, which was «gutted». The forest surrounding Elbląg […] is already stretching out its first branches toward it”.[40]

In the first years after the war, around 1,000 settlers from the East arrived in Elbląg each month.[41] Polish newspapers noted that the new inhabitants would leave the town if that was not so hard to do.[42] Thus, the problem was not the lack of population, as German journalists claimed, but of housing. In one article I found a positive note about a Polish-German neighbourhood: “The relationship of the Poles to the few Germans has become conciliatory, even good, over time. Many are now related by marriage”.[43] However, the article promotes the idea that Poles dissolved the precious old town to erect housing blocs. Subtext: They didn’t appreciate the city’s German architecture.

The Polish examples silenced German heritage and followed the idea of the city as a living entity, too: A 1958 article alluding to the precarious living standards in “Trybuna Ludu” [The People’s Tribune] describes the city as “still harmed”.[44] Nevertheless, instead of highlighting the Germans’ influence and the destruction caused by the war, a cursory summary of the city’s historical affiliations portrays it as having always supported Polish interests.

AMBITIOUS city. Moreover, it was that for centuries. […] In 1454, after the Crusaders’ victory, it returned to the Republic that it faithfully served until its fall. It bravely supported Stephen Báthory[45] in his fight against rich and intractable Gdansk.[46]

Overall, the newspapers acknowledged the disastrous situation – embedded in the usual socialist narration of progress: Elbląg had risen from the ashes.[47] Like their German counterparts, Polish newspapers disregarded the question of who was to blame for its destruction, focusing instead on incorporating it into the mental and geographical map of the Polish People’s Republic.

The press clippings I scrutinised described how Polish and German neighbourhoods excluded each other. The aftermath of the war shifted the power relations between Poles and Germans, with Germans experiencing violence and destruction. In contrast, Poles who had experienced war trauma throughout the previous six years became owners of post-German houses. This is why narrating Elbing and Elbląg implies fundamentally different attitudes: The narrative arcs either follow a narrative of destruction and degradation[48] (from the German perspective) or one of genesis (from the Polish perspective), which includes ideas of winning over unfavourable situations.[49] What one side perceived as irreversibly damaged was framed by the other as a starting point for creation.

Interestingly, all statements assume that a city’s character is created by people, with its value dependent on its economic power. Of course, that is an essential factor in settling and securing a living. However, people are also attached to cities for non-material reasons – drawn by their atmosphere and essence, for instance. These are addressed in cartographic representations of the city.

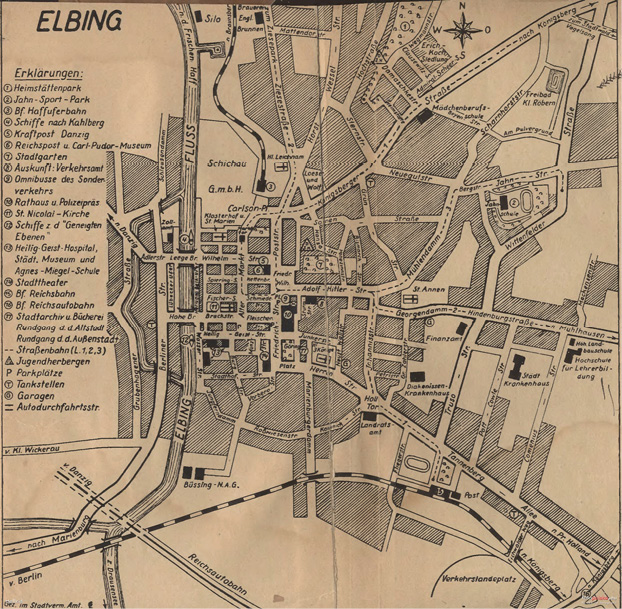

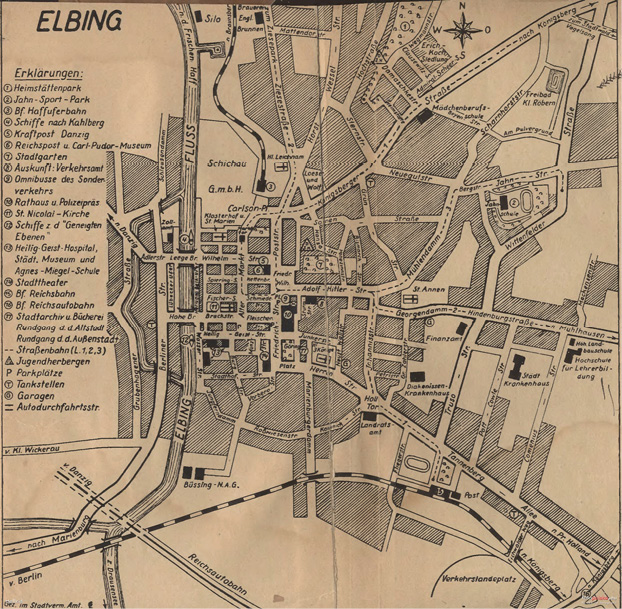

In secret material of the voivodship’s praesidium, Elbląg’s development plan starts by confirming that it “is a city inherited from the Germans”.[50] The protracted reconstruction process following retroversion only started in the late 1980s.[51] From the postwar years until 1989, all that one found there was vegetation and some isolated buildings. Nevertheless, the early Polish maps did not indicate an abandoned or destroyed city centre. Maps dating from 1937 (Map 1) and 1949 (Map 2) look basically the same, except for the new street names.

Map 1. F. Thebud, 700 Jahre Elbing: Festschrift zur Jubiläumswoche vom 21. bis 29. August, Elbing 1937

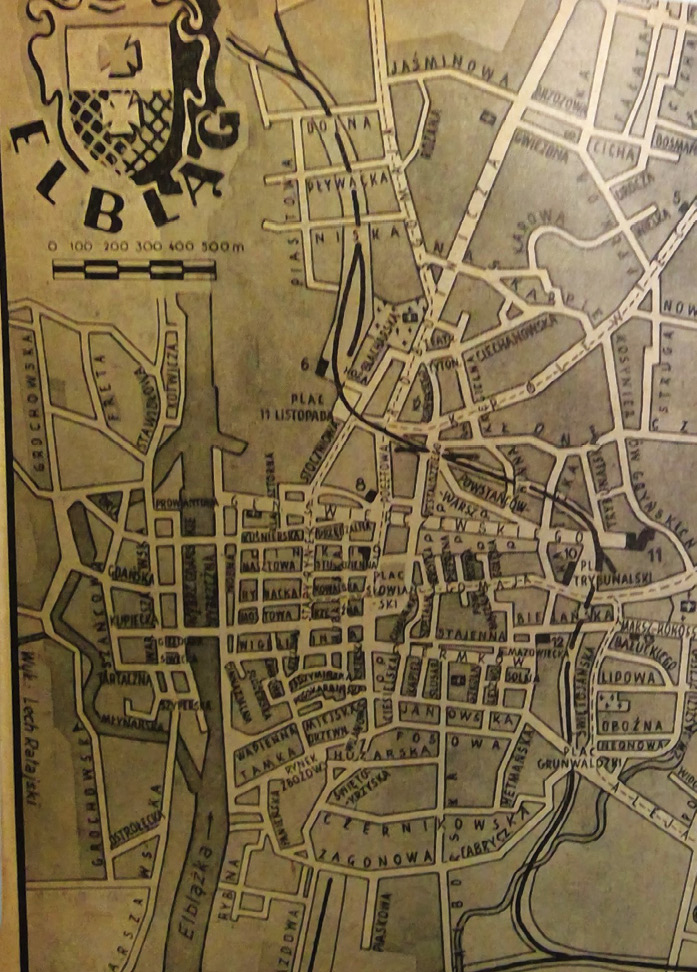

Map 2. M. and I. Bonkowicz-Sittauerowie, Elbląg i okolica, Warszawa 1949, p. 20+++

The Polish map is interesting insofar as it is taken from a tourism ministry publication.[52] The city that could offer almost nothing to its new settlers, who, in despair, often left it after a couple of days or weeks,[53] was reframed as a solid town with minimal infrastructure: Instead of monuments or historical sites, the map shows the employment office and local health authority. The tourist guide was addressing newcomers or seeking new inhabitants. With old pre-demolition photographs and references to its international Hanseatic-era (explicitly not German) atmosphere, the guide concludes, “[E]ven the ruins make it possible to imagine the ambience. The city deserves to be visited because, despite all the setbacks, it is reawakening”.[54] The few German architectural vestiges are criticised – as in the case of the “ugly balcony”[55] constructed in the Dominican church in the 19th century.

We need to bear in mind that to reproduce a two-dimensional version of reality, maps have to simplify. However, Map 2’s representation is very different from the reality. Why? Reading a map involves visibility, distinction, and recognition.[56] It goes from a general overview to drawing connections between the symbols and real life. In the third phase, we interpret the image, either rejecting it because the content seems irrelevant, or becoming confused and looking closer for the information we need. A map might also spark our interest because it calls into question our knowledge or expectations of a city. This is what happens here: The visual narrative stimulates our imagination about the city. Map reading allows our emotions to do a “cognitive qualification of places as safe/dangerous, friendly/unfriendly, relaxing/stressful, activating/demotivating, own/foreign”.[57] In this case, it is our notion of a safe and intact town. The map’s lack of any marked differences in tone (like hatching) renders the city one coherent unit.

Elbląg’s old town received more attention in the 1960s when tourist guides labelled the city ‘green’ and proposed a walking tour through the non-rebuilt, overgrown parts of the old town. In fact, on a very schematic map with no legend, the centre looks more like a park than an area that has not been revitalised in 20 years: “Today’s Elbląg is a green city and a city of gardens. This is obvious at first sight”.[58] The hatching used to illustrate Traugutt Park is the same as that for the city centre.[59] The text next to it describes Elbląg as a perfect starting point for nature lovers to discover the historical region of Warmia. Karolina Ciechorska-Kulesza explains the early emphasis on leisure activities as due to the “general climate of relief caused by the end of the war […] and the natural desire to rebound from the nightmare of the recent war, as well as the hardships of developing the city”.[60] This led to depicting a green city becoming more evident on coloured maps of the 1970s.[61] Colouring larger parts in green can be regarded as a strategy to stimulate the senses and evoke positive associations.[62]

In the example of mapped Elbląg we observe what Mikolaj Madurowicz calls the “emotional colonisation of the world”.[63] The narrative transformed from one of convergence – expressing the hope for reactivating and continuing the urban character[64] – to one of metamorphosis: “Today Elbląg has a green lung”.[65] Depicting the old town as a newly green area free of historical load and competing national claims was meant to present a “wholesale reorganisation”[66] of its urban character. It offers a more sensual approach, appreciating the very nature that contemporary German observers viewed as threatening civilisation (see footnote 40): “Along the emerald lawn, where artistic spatial forms are spread among the scattered trees”.[67]

Memoirs of settlers from Poland’s eastern territories show that the German buildings remaining in town stimulated recollections of the cruelty in German camps – a sign of how much the city needed positive rebranding.

Spacious brick stockades can induce anxiety: “Everyone looked beyond the buildings, and fear gripped us: What would we do within those walls? […] Everywhere, we saw solidly built houses and farm buildings. The building material was cement, brick and clay, not wood, like in our eastern region”.[68]

However, Poles living in Elbing before 1939 had also perceived the cityscape as threatening. Józef Murzynowski (b. 1919) praised the town for its density and coherent look but did not regard this as mainly “German”.[69] Due to the city’s militarily strategic function, Germans built many barracks for forced labour workers there; German-born Jürgen Haese recalled his mother terming them “predatory rabble”.[70] Required to do forced labour, Murzynowski lived with his family in one of the industrial barracks that “covered almost the whole city”[71] – a sign of how the Nazi authorities violently and rapidly took over the entire city. The city’s near-total demolition is not usually ascribed to human fate but rather the city’s destiny: What Murzynowski called “the tragedy of Elbląg”[72] principally referred to the irrevocable loss of its unique architecture.

Difficulties finding a place to live is a recurring issue in the memoirs. The city’s technical department urged postponing the expulsion of German skilled workers (plumbers, carpenters, bricklayers, etc.) to help speed the insufficient reconstruction process that could not accommodate the high number of settlers arriving every month.[73] In 1945, the Soviet, German and Polish power structure was reversed. According to Karolina Kuszyk, Poles’ violence against Germans was seen as legitimising Polishness.[74] Often, when fighting over an apartment or a room, a simple request sufficed to accelerate German deportations – a method that Murzynowski recalls too: “I experienced much evil from the Germans during the war, but still, I did not want to have a German family thrown out on the street – with small children”.[75] Murzynowski uses both German and Polish street names in an attempt to create a multinational mental map of his hometown despite the torment he had suffered during the war. Polish memoirs published after 1989 directly address Soviet cruelties and Polish authorities’ actions, while German memoirs hide the agent (agens): “We were thrown out in 1945”.[76] Li Ewering (b. 1920) experienced an indistinct fear when passing the Russian Army Cemetery during her first visit to the city in 1996. She has little understanding of Poland’s war experience and scant knowledge of its history. She recalls, “ [T]oo many people were coming from Poland to Elbing […]. [T]here was not enough Lebensraum for us”.[77] The word for the Nazi concept of territories that Germans wanted to take over for expansion is politically charged. The historian Maren Röger argues that there was little consciousness on the part of Elbing-born Germans regarding the German occupation authorities’ violent policies to create “racially clean areas”[78] through resettlement. A detailed description of parental homes is another frequent topic: As Ewering finally reaches her former house, she vividly recalls her childhood:

From the gable window, I thought I could hear my sister’s first screams of life from the gable as she was born. I thought of the beautiful, small apartment with the tiled stove. I saw my mother knitting on winter evenings […]. Do the people who live here have any idea of what happened here?[79]

According to Gaston Bachelard, the house is a condensation of the human need for positive memories. A house – with its eternal structure and solid foundation – literally and figuratively accommodates all memories. The more differentiated the literary image of a house is, the more places of refuge it offers for memories.[80] An individual’s need for continuity can explain the prominence and detail of house descriptions – giving meaning to urban fabric “that does not care who is living here”.[81] However, this post-1989 view of Elbląg is self-centred. It shows little concern for how current inhabitants feel when former residents visit. Jürgen Haese continued photographing his grandparents’ house despite being aware of “unfriendly glances”.[82] Realising the city’s identity change (“What can Elbląg tell a person from Elbing?”[83]), he assumes that the Poles still need to come to terms with the city’s multinational history. “For them, there are still too many brick houses left, medieval and neo-Gothic, [which are] unmistakable signs of the city of Elbing’s long existence”.[84] In Haese’s autobiographic novel, the Poles’ negative opinion is rooted in the dominance of the year 1945. For the 10-year-old boy, the destruction he witnessed was apocalyptic.

The road is no longer recognisable. It is full of debris, interspersed with abandoned guns, tanks, and other war equipment that stands as if fixed in a sticky sludge of melted snow and ash. It is a humid day; fog presses the smell down and does not let it escape, this penetrating, sweetish smell. Only later does Jürgen learn that that is the smell of decay. He turns around, searching. It is not possible that this desert was a city that had grown over centuries – where people lived, in need or in abundance, where happy years followed those of misery, where technical progress took hold: Electricity, streetcars, cars. There is no more sign of that: All is gone, wiped out by two weeks of war. The silence, and above all, the unspoiled scenery, gives it a ghostly feel. It seems like a memorial, as if someone had decreed: Leave everything as it is! Nothing is more frightening than reality! Whoever sees this must say: “No more war”.[85]

Haese cannot deny his alienation as he walks through contemporary Elbląg at the age of 70. The novel’s more distanced third-person narrative allows him to analyse his reluctance to meet people from the past more deeply. “And he does not want to have his unreliable fragments of memory, with which he has built a house according to his taste, subjected to scrutiny. Life lies would come to light”.[86] Again, it is the house metaphor that unites all childhood memories. For Haese, the positive parts of his early childhood and the blurred pictures he claims to have are the main points of reference to his youth and his personal truth. They ensure a linear narrative, or as De Certeau wrote, “[T]he past, the present and the future give the house different kinds of dynamism, often interfering, sometimes opposing, sometimes mutually stimulating dynamism. In the life of the human being, the house excludes coincidences; it increases its care for continuity”.[87]

The autobiographical accounts position the urban space in the narrative plot of divergence. Acknowledging different but coexisting points of view, they underline the nonlinearity of urban narratives.

So far, we have seen how a city is viewed as a living organism to whom human traits are ascribed. The exhibition Elbląg reconditus[88] is an example of anthropomorphising taken further: The city itself recounts its history, reflecting on what humankind has done to it over the centuries. Notably, it cannot distinguish between nations or groups: “Finally, the peoples who later transformed into my alive, breathing matter”.[89] Its emotions vary through history: It fears settlers and manmade catastrophes such as sieges, battles, and pillages. However, efforts to shape the city to human needs seem pointless because the only thing that will persist eternally is the town: Peoples have come and gone throughout its history. “My story, however, keeps underground the skeletons of people much more terrifying. My story is not only about the war. Thousands of human beings were trampled into the ground. Without shame, without fear, without embarrassment”.[90] The city claims that humans are always doomed to fail because they crave stability and sense. Their hybris does not let them recognise their weakness. “I remove everything from myself”,[91] says the city. One exhibition poster mirrors the relation between the city and the peoples who have tried to shape it, inscribing Elbląg’s various national affiliations in the pupil of an eye: Prussia, the Teutonic Knights, the Jagiellonian dynasty, the royal elections in Poland, the Kingdom of Prussia, the German Empire, the Third Reich, and postwar Poland. Instead of eyelashes, we see sabres, epees, swords, and spades that symbolise peoples’ violence – toward each other and their abuse of the town and its resources. Nonetheless, the town feels for its inhabitants. Regarding its inhabitants expelled after World War II, we read,

Every now and then, someone in this strange, circular queue would fall down from exhaustion or only pretend in order to stare just a little bit longer at the house, the canal, and the town. The next day, not many were left… […]; the farewell whispers fell down on me, and they rooted in me.[92]

The inhabitants’ experiences inscribe themselves in the city›s memory, similar to Zygmunt Barczyk’s findings on urban corporeality: Although a city never forgets, it is strong enough to move on after a crisis. “The city has more chances than a single human being, but just like them, it also risks sudden downs, depression, death”.[93] In the section about Elbląg’s newly settled inhabitants called Hope, the city’s despair and mutual dependence are apparent: “I tried to shake my wall like a dog that waves its tail when someone enters the house… Even if its owner died […], I was supposed to be once again, to lift my sore body from the ground. And they were walking, oh God, walking as if pushed by your hand”.[94]

The exhibit’s main message is that the city and its inhabitants are mutually dependent. Elbląg cannot develop without people, and without appropriate care (managing its resources, making it livable), its citizens risk destroying their livelihoods. Since nationalities and historical events are hard to identify, all the allusions require much historical knowledge if the exhibition should be understood as a ‘classic’ approach to representing local history. Being aware of the “comparatistic optimism”,[95] thinking the exhibition as an attempt to decolonise urban development can provide a basis to discuss what urban history can contribute to our understanding of transnational relations. Urban development is determined by authorities with political agendas that inevitably mark the city with what is later acknowledged as evidence of particular periods. However, such changes from ‘above’ always suppress the voices of marginalised (ethnic, religious) groups. A decolonial approach can thus stimulate people to actively participate and democratise urban development during large-scale resettlement and migration. It also stimulates us to rethink our behaviour in dealing with the environment.

Most German and Polish sources indicate emotional colonisation: infusing a place with emotions and justifications for including it in the national imaginary in the form of press clippings, personal memoirs, and autobiographical literature. Post-1989 personal narratives frame the city as Polish, not German. Polish witnesses show more empathy, acknowledging that others might see things differently. In contrast, German journalists’ condemnation of the city represented efforts at self-empowerment that shirked all responsibility for the war. In periods of censorship and vehement political rhetoric, Polish texts employed the narrative of “progress”. However, the maps present a more complex image: The basic design of some postwar tourist maps evokes an empty, abandoned, and neglected city, which is a more honest representation of Elbląg than that found in the texts. The maps can also be read as a new beginning: Visitors/settlers can begin their own emotional narratives on the blank sheet. The maps are more recipient-centered – more open to interpretation than ideological press clippings. Judgment may vary, but it is never indifferent. Maps encourage us to form our own opinions, while the accompanying texts try to convince us of a specific interpretation of a space. They are never merely decorative: They are tools to enrich our perception, inciting us to create meaning. In cartography, a reader-response approach combined with performative notions can help reveal counter-narratives. In periods of unambiguous political discourse, that is particularly important.

Stories of Elbing and Elbląg that have national narratives tend to view the city’s economic power as the main factor for social progress. The exhibition Elbląg reconditus attempts to view its urban and social fabric as persisting regardless of the categories used to ascribe meaning to the city. Its history shows that the city may change appearance and atmosphere and be affected by various catastrophes but its inhabitants will continue to live together and contribute new narratives to its houses – as the Kult band described, observing each other from behind the curtains with curiosity, irritation, and sorrow.

Elbing, Press clippings archive of the Herder Institute for Historical Research on East Central Europe, Marburg, Signature P 0325.

Ewering L., Heimat. Marienburg Elbing Frauenburg, Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Signature XI E 2 Ewe 1996.

Miejska Rada Narodowa i Zarząd Miejski w Elblągu, Komisja odbudowy i planowania, Archiwum Państwowe w Malborku, Signature 1, folder 454.

Miejska Rada Narodowa i Zarząd Miejski w Elblągu, Sprawy ogólne dot. odbudowy, Archiwum Państwowe w Malborku, Signature 1, folder 466.

Prezydium Miejskiej Rady Narodowej, Długofalowe plany inwestycyjne, m.in. projekt planu inwestycyjnego na 1953 r. oraz plan perspektywiczny rozwoju do 1960 r., Archiwum Państwowe w Malborku, Signature 53, folder 460.

Kult, Arahja, 1988, https://lyricstranslate.com/de/arahja-arahja.html-0, [accessed March 2, 2023].

Oxford English Dictionary, https://www.oed.com/oed2/00169695 [accessed: March 3, 2023].

Romantische Straße Touristik Arbeitsgemeinschaft GbR, https://www.romantischestrasse.de/en/romantische-strasse/germanys-oldest-and-most-popular–holiday-route [accessed: March 5, 2023].

Abramowicz M., Brosz M., Bykowska-Godlewska B., Michalski T., Strzałkowska A., Wzorce konsumpcji alkoholu. Studium socjologiczne, Kawle Dolne 2018.

Ackermann F., Palimpsest Grodno. Nationalisierung, Nivellierung und Sowjetisierung einer mitteleuropäischen Stadt, Wiesbaden 2010.

Alles Leben ist aus der Stadt gewichen, „Ost-West Kurier” 1959, September 3.

Bachelard G., Poetik des Raumes, Frankfurt am Main–Berlin–Wien 1975.

Barczyk Z., Miasto i sens, Katowice 2020.

Bonkowicz-Sittauerowie M. and I., Elbląg i okolica, Warszawa 1949.

Ciechorska-Kulesza K., Tożsamość a przestrzeń w warunkach niestabilnych granic. Przypadek byłego województwa elbląskiego, Gdańsk 2016.

Czarnocki K., Elbląg. Informator turystyczny, Warszawa 1968.

Elbing – die alte ostpreußische Schichaustadt über dem Haff, “Landeszeitung Lüneburg” 1957, November 4.

Elbing die verruchte Stadt, “Göttinger Presse” 1957, December 3.

Elbing ist eine tote Stadt, “Spandauer Volksblatt” 1960, February 7.

Elbląg. Plan miasta. 1974, PTTK, Sign. 04242.

Elbląg wciąż pokrzywdzony, “Trybuna Ludu” 1959, July 8.

Gieba K., A post-German city as a palimpsest in contemporary prose of the Lubuskie Land, “The Polish Review” 2022, no. 2.

Gliniecki T., Elbląskie okruchy XX wieku, Elbląg 2013.

Goddard C., Wierzbicka A., Cultural scripts. What are they, and what are they good for?, „Intercultural Pragmatics“ 2004, no. 2.

Göttinger Arbeitskreis, Die deutschen Ostgebiete jenseits von Oder und Neiße im Spiegel der polnischen Presse, Würzburg 1958.

Haese J., Verloren in Elbląg. Autobiographischer Roman, Osnabrück 2007.

Hahn H. H., Hahn E., Flucht und Vertreibung, [in:] É. François, H. Schulze, Deutsche Erinnerungsorte: Eine Auswahl, Bonn 2005.

Halikowska-Smith T., The past as palimpsest. The Gdańsk school of writers in the 1980s and 1990s, “The Sarmatian Review” 2003, no. 1.

Hiemer E.-M., Autobiographisches Schreiben als ästhetisches Problem, Wiesbaden 2019.

Hiemer E.-M., The Family as ‘Best Weapon’. Instrumentalising German health care discourses in Upper Silesia during the Interwar Period, “Journal of Family History” 2023, no. 3.

Hryniewicka M., Danzig, Gdańsk und seine Geschichte als literarisches Thema in der Prosa von Günter Grass, Stefan Chwin und Paweł Huelle, Göttingen 2008.

Kijowska J., Kijowski A., Rączkowski W., Politics and Landscape Change in Poland. C. 1940–2000, [in:] D. Cowley, R. Standring, M. Abicht, Landscapes through the lens: Aerial photographs and historic environment, occasional publication of the Aerial Archaeology Research Group, Vol. 2, Oxford–Oakville 2010.

Knigge A., „Die vor uns hier gelebt haben”: Spurensuche in der polnischen Literatur nach 1989, [in:] R. Jaworski, Gedächtnisorte in Osteuropa. Vergangenheiten auf dem Prüfstand, Frankfurt 2003.

Kołodziejczyk D., Huigen S., Multimodal palimpsests: Ideology, (non-)memory, affect and the senses in cultural landscapes construction in Eastern and Central Europe, “European Review” 2022, no. 4.

Kuhstall im Keller, „Eßlinger Zeitung” 1961, December 21.

Lubocka-Hoffmann M., Miasta historyczne Zachodniej i Północnej Polski: Zniszczenia i programy odbudowy, Elbląg 2004.

Lubocka-Hoffmann M., Powojenna odbudowa miast w Polsce a retrowersja Starego Miasta w Elblągu. The post-war rebuilding of towns and cities in Poland and the retroversion of the Old Town in Elbląg, „Ochrona Zabytków” 2019, no. 1.

Madurowicz M., Emocje zapisane na mapach, „Białostockie Studia Literaturoznawcze” 2019, no. 15.

Miasto z ambicjami, „Kurier Polski” 1960, August 17.

Murzynowski J., Ruiny i ludzie, [in:] …ocalić od zapomnienia: Półwiecze Elbląga (1945–1995) w pamiętnikach, notatkach i materiałach wspomnieniowych ludzi Elbląga, ed. R. Tomczyk, Elbląg 1997.

Musiaka Ł., Spatial transformations of selected Masurian cities in the years 1945–1989 in light of qualitative research of their inhabitants, “Prace Komisji Krajobrazu Kulturowego. Dissertations of Cultural Landscape Commission” 2019, no. 2.

My, Elblążanie, „Trybuna Ludu”, May 20, 1959.

Orski M., Filie obozu koncentracyjnego Stutthof na terenie miasta Elbląga w latach 1940–1945, Sztutow 1992.

Phillips J., Storytelling in Earth sciences. The eight basic plots, “Earth-Science Reviews” 2012, no. 3.

Portret ambitnego miasta, „Głos Pracy” 1960, May 10.

Przed 17 laty na cmentarzysku-Elblągu, „Express Wieczorny” 1962, February 12.

Roth R., Cartographic design as visual storytelling: Synthesis and review of map-based narratives, genres, and tropes, “The Cartographic Journal” 2021, no. 1.

Röger M., Flucht, Vertreibung und Umsiedlung. Mediale Erinnerungen und Debatten in Deutschland und Polen seit 1989, Marburg 2010.

Schneege H.-G., Langsam frißt der Wald die Stadt auf, “Passauer Neue Presse” 1958, April 5.

Sywenky I., (Re)constructing the urban palimpsest of Lemberg/Lwów/Lviv. A case study in the politics of cultural translation in East Central Europe, “Translation Studies” 2014, no. 2.

Wiedersehen mit Elbing, “Schwäbische Zeitung” 1958, February 21.

Zduniak-Wiktorowicz M., Filologia w kontakcie. Polonistyka, germanistyka, postkolonializm, Poznań 2018.

Żmudzińska-Nowak M., Heritage as a palimpsest of valued cultural assets on the problems of frontier land architectural heritage in turbulent times. Example of Poland’s Upper Silesia, “International Journal of Conservation Science” 2021, no. 3.