The myth of Heracles, identified by the Romans as Hercules, like many others in Greek and Roman mythology, has undergone various changes since the early accounts of Hesiod helped to consolidate its essential elements and characteristics. In this paper I will focus on only one selected aspect of the myth of this well-known hero, namely to show how the myth of Heracles and Geryon changed from Hesiod to the period of late antiquity, both in Greek and Roman literature, hence I will use both the name Heracles and Hercules, depending on the source cited. In the literature we can find several both Polish and foreign studies of the Heracles/Hercules myth as seen from different perspectives, such as archaeology, art or architecture (Corzo Sánchez 2005; Vigo 2010; González García 1997; Oria Segura 1996; Plácido 1990; Blázquez Marínez 1984; Szoka 2010; de Sanctis 2011; Hernández de la Fuente 2012; Pietrzak-Thébault 2012; Boczkowska 1993; Banach 1984; Wojciechowski 2005; Barbarzak 2018; Eisenfeld 2018; Blanco Robles 2019). My reflections supplement and elaborate on the considerations of the above-mentioned authors. For the sake of order, they have been divided into three parts. In the first part, I will compare how the various authors positioned the myth of Heraclesʼ stealing of oxen; in the second part, I will look at the portrayal of the figure of Geryon. Finally, the descriptions of Heraclesʼ course and achievements in the Iberian Peninsula will be analysed.

The first information concerning Heraclesʼ tenth labour is given to us by Hesiod and, as it were, it will form the starting point for further considerations. The poet provides us in a strictly genealogical manner with both information about Geryon, the three-pronged ʻmonsterʼ, about Heraclesʼ deed, about the other protagonists of the events, the dog Orthos or the shepherd Eurytion, and about the location of the whole event, namely Erythea.[1] The purpose of the Hesiodic heroʼs expedition appears to be merely to cleanse the world of monsters, and he visits Iberia to steal Geryonʼs oxen. However, the Beotian poet does not give the exact reason for Heracles to do this deed, nor the tasks imposed on him by Eurystheus. It is worth quoting the words of the poet at this point and drawing attention to all the elements of the myth, which will be analysed in detail later in the article, namely, the location of the action, the characters involved and the course of the story itself:

Χρυσάωρ δ᾽ ἔτεκεν τρικέφαλον Γηρυονῆα

μιχθεὶς Καλλιρόῃ κούρῃ κλυτοῦ Ὠκεανοῖο.

τὸν μὲν ἄρ᾽ ἐξενάριξε βίη Ἡρακληείη

290 βουσὶ παρ᾽ εἰλιπόδεσσι περιρρύτῳ εἰν Ἐρυθείῃ

ἤματι τῷ ὅτε περ βοῦς ἤλασεν εὐρυμετώπους

Τίρυνθ᾽ εἰς ἱερὴν διαβὰς πόρον Ὠκεανοῖο

Ὄρθον τε κτείνας καὶ βουκόλον Εὐρυτίωνα

σταθμῷ ἐν ἠερόεντι πέρην κλυτοῦ Ὠκεανοῖο. (Theog. 287˗295)

Khrysaor (Chrysaor), married to Kallirhoe (Callirhoe), daughter of glorious Okeanos (Oceanus), was father to the triple-headed Geryon, but Geryon was killed by the great strength of Herakles at sea-circled Erytheis (Erythea) beside his own shambling cattle on that day when Herakles drove those broad-faced cattle toward holy Tiryns, when he crossed the stream of Okeanos and had killed Orthos and the oxherd Eurytion out in the gloomy meadow beyond fabulous Okeanos. (Transl. by Evelyn-White)

and elsewhere in the Theogony Hesiod mentions:

κούρη δ᾽ Ὠκεανοῦ, Χρυσάορι καρτεροθύμῳ

980μιχθεῖσ᾽ ἐν φιλότητι πολυχρύσου Ἀφροδίτης,

Καλλιρόη τέκε παῖδα βροτῶν κάρτιστον ἁπάντων,

Γηρυονέα, τὸν κτεῖνε βίη Ἡρακληείη

βοῶν ἕνεκ᾽ εἰλιπόδων ἀμφιρρύτῳ εἰν Ἐρυθείῃ. (Theog. 979˗983)

Kallirhoe (Callirhoe), daughter of Okeanos (Oceanus) lying in the embraces of powerful-minded Khrysaor (Chrysaor) through Aphrodite the golden bore him a son, most powerful of all men mortal, Geryones, whom Herakles in his great strength killed over his dragfoot cattle in water-washed Erytheia [the Sunset Isle]. (Transl. by Evelyn-White)

Location of the mythical story

It is first necessary to consider issues relating to the location and nature of Iberia itself, and then the reason and manner in which Heracles found himself in the Iberian Peninsula, so far from his native Greece. It is worth noting that the very location of Iberia in antiquity was by no means clear and obvious.[2] In their colonisation expeditions across the Mediterranean, the Greeks reached the most remote lands, including those in the western part of Europe. There, believing there was nothing further, they began to relocate the location of certain mythological sites, such as the Garden of Hesperides, where golden apples grew. Perhaps this was linked to the wealth of the region, which, according to Strabo’s account (11.2.19), abounded in gold-bearing streams and gold mines.[3] An example of the wealth of western Iberia may also have been the fabulously rich city, the Phoenician colony,[4] Tartessos.[5] However, it seems that back in the 5th century BC the Greeks were not clear that Western Iberia was a peninsula, and the term was expanded as the Atlantic frontiers were explored (Domínguez Monedero 1983: 205–211).

One of the main reasons for mythologising the image of Iberia was the fact that the Iberian Peninsula was located far from the world, that until the beginning of the 3rd century BC the Iberian Peninsula was remote from any significant centre of power. Western Iberia was seen by the Greeks as a remote and marginal land. The first news of this land was brought to Greece by Greek traders who ventured into the Western Mediterranean from the 7th century BC, the news, however, was apparently misleading and not very precise, but it stimulated the Greeksʼ imagination, because in this phase of exploration and colonisation everything was susceptible to interpretation within mythical schemes, sometimes confusing reality with fiction.

The Greeksʼ discovery of the ʻFar Westʼ was downright accidental. Herodotus writes of this when he recounts how, in the year 638 BC, Colaios of Samos arrived with his merchant ship at the island of Platea off the Libyan coast, when a storm drove his ship all the way beyond the Strait of Gibraltar. He then landed at Tartessos, on the Atlantic coast of modern Spain, from where he returned with a fabulously rich cargo that sparked the imagination of others about the riches of the lands of the West. Herodotus writes of this event in the following words in his Histories:

ἀποδημεόντων δὲ τούτων πλέω χρόνον τοῦ συγκειμένου τὸν Κορώβιον ἐπέλιπε τὰ πάντα, μετὰ δὲ ταῦτα νηῦς Σαμίη, τῆς ναύκληρος ἦν Κωλαῖος, πλέουσα ἐπ᾽ Αἰγύπτου ἀπηνείχθη ἐς τὴν Πλατέαν ταύτην: πυθόμενοι δὲ οἱ Σάμιοι παρὰ τοῦ Κορωβίου τὸν πάντα λόγον, σιτία οἱ ἐνιαυτοῦ καταλείπουσι. αὐτοὶ δὲ ἀναχθέντες ἐκ τῆς νήσου καὶ γλιχόμενοι Αἰγύπτου ἔπλεον, ἀποφερόμενοι ἀπηλιώτῃ ἀνέμῳ: καὶ οὐ γὰρ ἀνίει τὸ πνεῦμα, Ἡρακλέας στήλας διεκπερήσαντες ἀπίκοντο ἐς Ταρτησσόν, θείῃ πομπῇ χρεώμενοι. τὸ δὲ ἐμπόριον τοῦτο ἦν ἀκήρατον τοῦτον τὸν χρόνον, ὥστε ἀπονοστήσαντες οὗτοι ὀπίσω μέγιστα δὴ Ἑλλήνων πάντων τῶν ἡμεῖς ἀτρεκείην ἴδμεν ἐκ φορτίων ἐκέρδησαν, μετά γε Σώστρατον τὸν Λαοδάμαντος Αἰγινήτην: τούτῳ γὰρ οὐκ οἷά τε ἐστὶ ἐρίσαι ἄλλον. (Hdt. 4.152).

But after they had been away for longer than the agreed time, and Corobius had no provisions left, a Samian ship sailing for Egypt, whose captain was Colaeus, was driven off her course to Platea, where the Samians heard the whole story from Corobius and left him provisions for a year; [2] they then put out to sea from the island and would have sailed to Egypt, but an easterly wind drove them from their course, and did not abate until they had passed through the Pillars of Heracles and came providentially to Tartessus. [3] Now this was at that time an untapped market; hence, the Samians, of all the Greeks whom we know with certainty, brought back from it the greatest profit on their wares except Sostratus of Aegina, son of Laodamas; no one could compete with him. (Transl. by Godley).

This legendary and idealised image of Iberia was maintained by the Greek authors, and lasted until the time of the Roman writers, thanks to the debate that took place among Hellenistic authors who tried to find a precise geographical location for all the elements of the Greek mythological cycles, and to rationalise the mythical stories in a clear way (Gómez et al. 1995: 26–29, 51; Cabrero Piquero 2009: 18–19; Camacho 2013a: 9–30).

Various myths therefore began to be associated with western Iberia and the surrounding area, such as the Fortunate Isles (Str. 3.2.13, 3.3.13; Plut. Sert. 8), which Pliny the Elder (6.36.200–201; 6.37.202–204) and Pomponius Mela (3.9.99) also relate to the Isle of Gorgona, two of the twelve labours of Heracles, the tenth and the eleventh, the aforementioned Garden of the Hesperides (Stes. 8; Strab. 3.2.13; Diod. 4.17, 4.26), or also the myth of the erection of the famous Pillars of Hercules in the Strait of Gibraltar (Str. 3.5.5; Hdt. 4.8; Diod. 4.18.5; Apollod. 2.5.10; Mela Chor. 15.27; Sol. De mir. XXIII; Aelian 5.3).

The presence of Heracles in these remote latitudes also represented the arrival of a civilising element in these wild and hostile lands, as well as their incorporation into the terra cognita, marked precisely by the Pillars of Hercules, the boundary between the known and the unknown (Gómez et al. 1995: 93–103; Camacho 2013b).

It is first worth looking at where ancient authors locate the mythical events of which Heracles is the protagonist. We find information on this subject in many significant writers of antiquity. The starting point for our considerations remains the seaswept Erythea mentioned by Hesiod (Theog. 290, 983). The Beotian poet locates the myth on an island. Unfortunately, it seems too simple for us now to look at a map and discover the corner described by Hesiod. Assuming that he only knew it from stories, and that those concerning Heracles were, after all, complete fiction, finding the right place appears to be a difficult task. This place is also mentioned by Stesichorus. The lyrical poet, who lived in the sixth century BC, conveys in the Geryoneis poem, which we know from only a few fragments, that the events described took place ‘almost opposite famous Erytheiaʼ (Stes. Frg. S7: σχεδὸν ἀντιπέρας κλεινᾶς Ἐρυθείας). The same information repeats in the fifth century BC Euripides in his tragedy Heracles furens, which tells the story of human madness (Czerwińska 2006: 87–111). We learn from the drama that Heracles, having spread venom from a defeated hydra on his darts, killed the shepherd of Erythea, a monster with three bodies (423). More detailed information on the location of the myth appears in the work of Herodotus. In Book IV, in which the author presents Dariusʼ expedition against the Scythians and their history, information concerning the events of interest to this article also appears. Herodotus writes:

Σκύθαι μὲν ὧδε ὕπερ σφέων τε αὐτῶν καὶ τῆς χώρης τῆς κατύπερθε λέγουσι, Ἑλλήνων δὲ οἱ τὸν Πόντον οἰκέοντες ὧδε. Ἡρακλέα ἐλαύνοντα τὰς Γηρυόνεω βοῦς ἀπικέσθαι ἐς γῆν ταύτην ἐοῦσαν ἐρήμην, ἥντινα νῦν Σκύθαι νέμονται. Γηρυόνεα δὲ οἰκέειν ἔξω τοῦ Πόντου, κατοικημένον τὴν Ἕλληνές λέγουσι Ἐρύθειαν νῆσον τὴν πρὸς Γαδείροισι τοῖσι ἔξω Ἡρακλέων στηλέων ἐπὶ τῷ Ὠκεανῷ. τὸν δὲ Ὠκεανὸν λόγῳ μὲν λέγουσι ἀπὸ ἡλίου ἀνατολέων ἀρξάμενον γῆν περὶ πᾶσαν ῥέειν, ἔργῳ δὲ οὐκ ἀποδεικνῦσι. (Hdt. 4.8)

This is what the Scythians say about themselves and the country north of them. But the story told by the Greeks who live in Pontus is as follows. Heracles, driving the cattle of Geryones, came to this land, which was then desolate, but is now inhabited by the Scythians. Geryones lived west of the Pontus, settled in the island called by the Greeks Erythea, on the shore of Ocean near Gadira, outside the pillars of Heracles. As for Ocean, the Greeks say that it flows around the whole world from where the sun rises, but they cannot prove that this is so. (Transl. by Frazer)

It seems, therefore, that according to the author of the Histories, Erythea was an island near the city of Gades (now Cadiz).[6] Such information is also reproduced by Pseudo-Apollodorus, who, in a compendium of Greek myths compiled in a collection entitled the Bibliotheca, attributed to him, states that:

δέκατον ἐπετάγη ἆθλον τὰς Γηρυόνου βόας ἐξ Ἐρυθείας κομίζειν. Ἐρύθεια δὲ ἦν Ὠκεανοῦ πλησίον κειμένη νῆσος, ἣ νῦν Γάδειρα καλεῖται. ταύτην κατῴκει Γηρυόνης Χρυσάορος καὶ Καλλιρρόης τῆς Ὠκεανοῦ… (Apollod. 2.5.10)

As a tenth labour he was ordered to fetch the king of Geryon from Erythia. Now Erythia was an island near the ocean; it is now called Gadira. This island was inhabited by Geryon, son of Chrysaor by Callirrhoe, daughter of Ocean. (Transl. by Frazer)

Another Greek author, namely Diodorus of Sicily, who lived in the first century BC in the longest historical work of antiquity, the Bibliotheca historica, in Book IV on the history of the Greeks, mentions events that took place in Iberia. The historian writes:

Εὐρυσθέως δὲ προστάξαντος ἆθλον δέκατον τὰς Γηρυόνου βοῦς ἀγαγεῖν, ἃς νέμεσθαι συνέβαινε τῆς Ἰβηρίας ἐν τοῖς πρὸς τὸν ὠκεανὸν κεκλιμένοις μέρεσιν… (Diod. 4.17.1)

Eurystheus then enjoined him [Herakles] as a tenth Labour the bringing back of the cattle of Geryones, which pastured in the parts of Iberia which slope towards the ocean. (Transl. by Oldfather)

Further information on the location of the myth of Heracles and Geryon appears in the works of Roman authors. It is mentioned by Pomponius Mela in his work Chorographia. Pomponius was from the nearby town of Tingentera (2.96), and was therefore personally familiar with the subject and locations (Szarypkin 2011: 13–14). His text includes a description of the location of the island of Gades and the sanctuary of Hercules there (3.6.46), also the island of Erythea itself:

in Lusitania Erythia est quam Geryonae habitatam accepimus, aliaeque sine certis nominibus; adeo agri fertiles, ut cum semel sata frumenta sint, subinde recidivis seminibus segetem novantibus, septem minime, interdum plures etiam messes ferant. (Mela 3.47)

In Lusitania there is Eythia, which we are told was the home of Geryon, and other islands without fixed names. The fields of Eryhia are so fertile that as soon as grain is planted, as soon as the seed falls to the ground and renews the crops, they produce at least seven harvests, sometimes even more. (Transl. by Romer)

Pliny the Elder, on the other hand, gives a very detailed geographic vision of the region, in which he describes two islands beyond the Strait of Gibraltar, one of which is undoubtedly Erythea. The author writes:

ab eo latere, quo Hispaniam spectat, passibus fere C altera insula est, longa M passus, M lata, in qua prius oppidum Gadium fuit. vocatur ab Ephoro et Philistide Erythea, a Timaeo et Sileno Aphrodisias, ab indigenis Iunonis. maiorem Timaeus Cotinusam aput eos vocitatam ait; nostri Tarteson appellant, Poeni Gadir, ita Punica lingua saepem significante. Erythea dicta est, quoniam Tyri aborigines earum orti ab Erythro mari ferebantur. in hac Geryones habitasse a quibusdam existimatur, cuius armenta Hercules abduxerit. sunt qui aliam esse eam et contra Lusitaniam arbitrentur, eodemque nomine quandam ibi appellant. (Nat. hist. 4.120)

On the side facing Hispania at a distance of about 100 yards is another island one mile long and one mile broad, on which the town of Gadis was previously situated; Ephorus and Philistus call this island Erythea (…) It was called Erythea, because the original ancestors of the Carthaginians, the Tyrians, were said to have come from the Red Sea. This island is believed by some people to have been the home of the Geryones whose cattle were carried off by Hercules; but others hold that that was another island, lying of Lusitania, and that an island there was once called by the same name. (Transl. by H. Rackham)

Finally, Solinus, who lived in the third century, describes the location of theft of oxen as follows:

in capite Baeticae, ubi extremus est noti orbis terminus, insula continenti septingentis pedibus separatur, quam Tyrii a Rubro profecti mari Erythream, Poeni lingua sua Gadir id est saepem nominaverunt. in hac Geryonem aevum agitavisse plurimis monumentis probatur, tametsi quidam putent Herculem boves ex alia insula abduxisse, quae Lusitaniam contuetur. (De mir. XXIII.12)

At the tip of Betics, where the edge of the world as we know it is, is an island 700 feet from the mainland, which the Tyrians who came from the Red Sea called Eritrea. The Phoenicians called it Gadir, meaning border, in their language. Many monuments attest to the fact that Geryon lived there, while others claim that Hercules led oxen from another island closer to Lusitania. (Transl. by the author)

With regard to the location of the myth, the accounts of various authors seem to converge. They report that Erythea was an island and was located in the Gadir area. Literary sources date the founding of the city, as a Phoenician (Tyrian) colony, to the 11th century BC,[7] but the earliest archaeological data from the site date only to the 8th century. The illustrations below show that Gades laid on three islands (Fig. 1). A Phoenician settlement was established on Erythea, which is now part of the mainland (Fig. 2). There the temple of Astarte (identified with Aphrodite) was located, hence it was called Aphrodisias. To the north of Erythea, there was a second larger island, Gades nova (Gadeira), and to the south, a third island, now Sancti Petri, where there was a temple in honour of the Phoenician god Melquart, identified sometimes with Hercules.[8]

Fig. 1. The Bay of Cádiz in antiquity featuring a notably different coastline.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C%C3%A1diz#/media/File:Gadeiras314.svg (access 30.06.2022).

Fig. 2. Satellite [contemporary] view of the Bay of Cádiz. European Space Agency – Seville, Spain. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C%C3%A1diz#/media/File:(Bah%C3%ADa_de_C%C3%A1diz)_Seville,_Spain_(49104522676)_(cropped).jpg CC BY-SA 2.0 (access 30.06.2022).

The figure of Geryon

Another element of the literary accounts that is worth a closer look is the depiction of the mythological figure of Geryon. The first time we encounter the description of Geryon is the work of Hesiod Theogony (287–288), in which he stated that Geryon was a “three-headed monster” (ʻtrikefalosʼ) who probably had only one common body. Elsewhere, however, Hesiod portrays Geryon as ‘the bravest son among mortals’ (Theog. 979–983), attributing to him some heroic qualities.[9] The figure of Geryon appears in Aeschylus’s tragedy Agamemnon (872–873) and Euripides’s drama Hercules furens (423). The tragedians describe him in a different way to Hesiod, namely presenting him as a figure with three bodies.

εἰ δ᾽ ἦν τεθνηκώς, ὡς ἐπλήθυον λόγοι,

τρισώματός τἂν Γηρυὼν ὁ δεύτερος

πολλὴν ἄνωθεν, τὴν κάτω γὰρ οὐ λέγω,

χθονὸς τρίμοιρον χλαῖναν ἐξηύχει λαβεῖν,

ἅπαξ ἑκάστῳ κατθανὼν μορφώματι. (Aesch. Agam. 869–873)

Or if he had died as often as reports claimed, then truly he might have had three bodies, a second Geryon, and have boasted of having taken on him a triple cloak of earth, one death for each different shape. (Aesch. Agam. 869–870; transl. by Vellacott)

τάν τε μυριόκρανον

πολύφονον κύνα Λέρνας

ὕδραν ἐξεπύρωσεν,

βέλεσί τ᾽ ἀμφέβαλ᾽ ἰόν,

τὸν τρισώματον οἷσιν ἔ-

κτα βοτῆρ᾽ Ἐρυθείας. (Eur. Herc. 419–424)

He [Heracles] burned to ashes Lernaʼs murderous hound, [420] the many-headed hydra, and smeared its venom on his darts, with which he slew the shepherd of Erytheia, a monster with three bodies. (Eur. Herc. 419–423; transl. by Vellacott)

The Sicilian poet Stesichorus, in the aforementioned poem Geryoneis, refers to Geryon as ʻa monster with three headsʼ.[10] Without any terms to describe this character further, Pindar mentions it in the Isthmian Ode (Istm. 1.1–3). A more precise description appears only in Apollodorus, who, probably follows the version of Stesichorus (Danielewicz 1984: LXXXVIII):

ταύτην κατῴκει Γηρυόνης Χρυσάορος καὶ Καλλιρρόης τῆς Ὠκεανοῦ, τριῶν ἔχων ἀνδρῶν συμφυὲς σῶμα, συνηγμένον εἰς ἓν κατὰ τὴν γαστέρα, ἐσχισμένον δὲ εἰς τρεῖς ἀπὸ λαγόνων τε καὶ μηρῶν. εἶχε δὲ φοινικᾶς βόας, ὧν ἦν βουκόλος Εὐρυτίων, φύλαξ δὲ Ὄρθος ὁ κύων δικέφαλος ἐξ Ἐχίδνης καὶ Τυφῶνος γεγεννημένος. (Apollod. 2.5.10)

This island was inhabited by Geryon, son of Chrysaor by Callirrhoe, daughter of Ocean. He had the body of three men grown together and joined in one at the waist, but parted in three from the flanks and thighs. He owned red kine, of which Eurytion was the herdsman and Orthus, the two-headed hound, begotten by Typhon on Echidna, was the watchdog. (Transl. by Frazer)

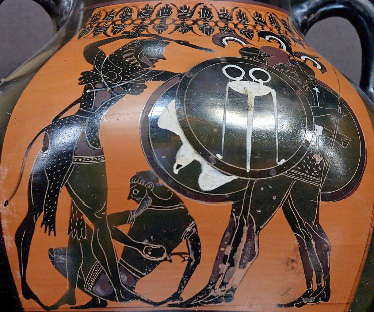

Apollodorus reproduces Hesiodʼs version of the origin of Geryon himself from Chrysaor and Callirhoe. In his description, he juxtaposes, as it were, earlier depictions by other authors who imagined him as a figure composed of three parts, three bodies or three heads. The description given by Apollodorus shows Geryon as a figure with three heads, one torso and six legs, i.e. he combines the earlier accounts. A similar image of the character of Geryon appeared on Athenian amphoras from the sixth century BC (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Heracles fighting Geryon (dying Eurytion on the ground). Side A from an Attic black-figure amphora. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Heracles_Geryon_Louvre_F55.jpg (access 30.06.2022).

In the following centuries, the fundamental image of Geryon as a triple figure is not transformed much. Subsequent descriptions will differ only in certain aspects. Lucretius (DRN 5.28) mentions him as the triple-twin creature with three torsos (tripectora tergemini vis Geryonai), which can also be translated as a triple figure with the strength of three torsos, or three men. Virgil in the Aeneid (6.289) writes about the ghost of three-bodied Geryon (forma tricorporis umbrae). Hyginus in one of his fables (Fab. 30.151), also reproduces a fixed pattern, when he writes about: ‘The triple-bodied Geryon, son of Chrysaor, he [Heracles] killed with a single weapon’[11]. The reference to this myth could not be missed also by Horace, who wrote in one of his Odes:

non, si trecenis quotquot eunt dies,

amice, places inlacrimabilem

Plutona tauris, qui ter amplum

Geryonen Tityonque tristi (Carm. 2.14.5–8)

Not though three hundred bullocks flame

Each year, to soothe the tearless king

Who holds huge Geryonʼs triple frame

And Tityos in his watery ring... (Transl. by Conington)

We find a similar image in Ovid, who in his Metamorphoses (9.184–185) mentions the triple Geryon, the Hiberian shepherd of oxen (nec me pastoris Hiberi/forma triplex, nec forma triplex tua, Cerbere, movit.). Pausanias, on the other hand, in describing the fate of Geryon’s encounter with Heracles exceptionally rationally states that:

[…] καὶ Ἡρακλέους ὁ πρὸς Γηρυόνην ἀγών: τρεῖς δὲ ἄνδρες Γηρυόνης εἰσὶν ἀλλήλοις προσεχόμενοι. (Peri. 5.19.1)

[Amongst the scenes depicted on the chest of Kypselos (Cypselus) at Olympia] The combat between Heracles and Geryones, who is represented as three men joined to one another. (Transl. by Jones)

In contrast, Diodorus of Sicily departed from the original version of the story, establishing a new narrative of the myth. Like other authors who used the myth of Geryon and Heracles to demonstrate their erudition, knowledge of mythology or for primarily literary purposes, the author of the compilation work the Bibliotheca Historica attempts to rationalise certain stories. Despite the harsh criticism of Diodorusʼ work, it is a valuable source of knowledge and reflection. He may also have drawn on sources that are unknown to us in his description of Geryon and related events. About Geryon himself he writes:

ἐπ᾽ αὐτὴν κύριοι κατέστησαν. ὁ δ᾽ Ἡρακλῆς πολλὴν τῆς Λιβύης ἐπελθὼν παρῆλθεν ἐπὶ τὸν πρὸς Γαδείροις ὠκεανόν, καὶ στήλας ἔθετο καθ᾽ ἑκατέραν τῶν ἠπείρων. συμπαραπλέοντος δὲ τοῦ στόλου διαβὰς εἰς τὴν Ἰβηρίαν, καὶ καταλαβὼν τοὺς Χρυσάορος υἱοὺς τρισὶ δυνάμεσι μεγάλαις κατεστρατοπεδευκότας ἐκ διαστήματος, πάντας τοὺς ἡγεμόνας ἐκ προκλήσεως ἀνελὼν καὶ τὴν Ἰβηρίαν χειρωσάμενος ἀπήλασε τὰς διωνομασμένας τῶν βοῶν ἀγέλας. (Diod. 4.18.2)

And after Herakles had visited a large part of Libya he arrived at the ocean near Gadeira, where he set up pillars on each of the two continents. His fleet accompanied him along the coast and on it he crossed over into Iberia. And finding there the sons of Chrysaor encamped at some distance from one another with three great armies, he challenged each of the leaders to single combat and slew them all, and then after subduing Iberia he drove off the celebrated herds of cattle. (Transl. by Oldfather)

He gives an interpretation of the earlier accounts of the triple figure which, from a rational point of view and a desire to show that there is a grain of historical truth hidden in the myths, albeit a history very distant in time, Diodorus repeats after Hesiod that the father was Chrysaor, but the triple perception of Geryon was not related to his appearance but rather the power associated with him. He therefore considered that the threefold body could be interpreted as three persons, and their association could mean that they worked closely together. Hence, they led three armies, but together they formed one body with three heads but numerous legs.

To summarise what has been discussed so far, the figure of Geryon is generally portrayed as a monster with three heads and/or bodies. We learn that he was most often the son of Chrysaor and Callirhoe, that he inhabited the island of Erythea, in the farthest west, by the Ocean, at the edge of the world known to the Greeks, that he raised red oxen, assisted by the shepherd Eurytion and the two-headed dog Orthos, brother of Cerberus, and that he was killed by Heracles. Perhaps the triple character could be interpreted as a hybrid of Geryon, Eurytion and Orthos, who together inhabited the island and defended the herd. Diodorus, however, opted for a different interpretation, in a more historical than mythological spirit, maintaining that there were three brothers and each had a large army, who appeared to have constituted one strong and fearsome body.

Heracles and the theft of the cattle

This part of the article looks at how ancient authors portray the events that unfolded between Heracles and Geryon. As it is well known, Heracles suffered punishment for murdering his children in a furious madness sent on him by the goddess Hera. He was expected to perform ten tasks that exceeded the strength of any man. In the end, he completed twelve of them, as two were not recognised by Eurystheus. One of these jobs, the tenth, was the abduction of Geryon’s cattle.[12] The mythological events are described by Hesiod in the Theogony (289–291).

Euripides, when referring to these events, mentions how Heracles, after slaying the hydra, killed the shepherd of Erythea, a monster with three bodies (Herc. 423). This event is also described by Herodotus, who wrote as follows:

Heracles, driving the cattle of Geryones, came to this land, which was then desolate, but is now inhabited by the Scythians. (c.f. Hdt. 4.8.1)

Information on stealing oxen also appears in Plato, in the dialogue Gorgias. The philosopher states that:

δοκεῖ δέ μοι καὶ Πίνδαρος ἅπερ ἐγὼ λέγω ἐνδείκνυσθαι ἐν τῷ ᾁσματι ἐν ᾧ λέγει ὅτι— “νόμος ὁ πάντων βασιλεὺς θνατῶν τε καὶ ἀθανάτων:”

οὗτος δὲ δή, φησίν,–

“ἄγει δικαιῶν τὸ βιαιότατον

ὑπερτάτᾳ χειρί: τεκμαίρομαι

ἔργοισιν Ἡρακλέος, ἐπεὶ – ἀπριάτας –”

λέγει οὕτω πως – τὸ γὰρ ᾆσμα οὐκ ἐπίσταμαι – λέγει δ᾽ ὅτι οὔτε πριάμενος οὔτε δόντος τοῦ Γηρυόνου ἠλάσατο τὰς βοῦς, (Plato. Gorg. 484b).

Pindar in the ode says – ‘Law the sovereign of all, mortals and immortals,’ which, so he continues, – ‘Carries all with highest hand, justifying the utmost force: in proof I take the deeds of Herakles, for unpurchased.’ . . . It tells how he drove off the cows as neither a purchase nor a gift from Geryones; taking it as a natural right that cows or any other possessions of the inferior and weaker should all belong to the superior and stronger. (Plato. Gorg. 484b; transl. by Burnet)

A slightly different version is presented by Apollodorus, who states:

πορευόμενος οὖν ἐπὶ τὰς Γηρυόνου βόας διὰ τῆς Εὐρώπης, ἄγρια πολλὰ ζῷα ἀνελὼν Λιβύης ἐπέβαινε, καὶ παρελθὼν Ταρτησσὸν ἔστησε σημεῖα τῆς πορείας ἐπὶ τῶν ὅρων Εὐρώπης καὶ Λιβύης ἀντιστοίχους δύο στήλας. θερόμενος δὲ ὑπὸ Ἡλίου κατὰ τὴν πορείαν, τὸ τόξον ἐπὶ τὸν θεὸν ἐνέτεινεν: ὁ δὲ τὴν ἀνδρείαν αὐτοῦ θαυμάσας χρύσεον ἔδωκε δέπας, ἐν ᾧ τὸν Ὠκεανὸν διεπέρασε. καὶ παραγενόμενος εἰς Ἐρύθειαν ἐν ὄρει Ἄβαντι αὐλίζεται. αἰσθόμενος δὲ ὁ κύων ἐπ᾽ αὐτὸν ὥρμα: ὁ δὲ καὶ τοῦτον τῷ ῥοπάλῳ παίει, καὶ τὸν βουκόλον Εὐρυτίωνα τῷ κυνὶ βοηθοῦντα ἀπέκτεινε. Μενοίτης δὲ ἐκεῖ τὰς Ἅιδου βόας βόσκων Γηρυόνῃ τὸ γεγονὸς ἀπήγγειλεν. ὁ δὲ καταλαβὼν Ἡρακλέα παρὰ ποταμὸν Ἀνθεμοῦντα τὰς βόας ἀπάγοντα, συστησάμενος μάχην τοξευθεὶς ἀπέθανεν. Ἡρακλῆς δὲ ἐνθέμενος τὰς βόας εἰς τὸ δέπας καὶ διαπλεύσας εἰς Ταρτησσὸν Ἡλίῳ πάλιν ἀπέδωκε τὸ δέπας. (Apollod. 2.108–109)

As Herakles proceeded through Europe to these cattle, he killed many wild animals, paid a visit to Libya, and went on to Tartessos (Tartessus) where he set up two steles opposite each other at the borders of Europe and Libya, as commemorative markers of his trip. Then, when Helios (the Sun) made him hot as he proceeded, he aimed his bow at the god and stretched it; Helios was so surprised at his daring that he gave him a golden goblet, in which he crossed Okeanos.

When he reached Erytheia he camped on Mount Atlas. The dog smelled him there and went after him, but he struck it with his club, and when the cowherd Eurytion came to help the dog, he slew him as well. Menoetes, who was there tending the cattle of Haides, reported these events to Geryon, who overtook Herakles by the Athemos (Athemus) river as he was leading away the cattle. They fought, and Herakles slew Geryon with an arrow. He then loaded the cattle into the goblet, sailed back to Tartessos, and returned the goblet to Helios. (Transl. by Frazer)

Hyginus writes of Heracles exterminating Geryon with a single bullet (30.151), and Pliny the Elder states that ʻSome think that there [Erythia] lived Geryon, to whom Hercules drove the flock.ʼ (Hist. nat. 4.120). Pausanias, in his Description of Greece, writes that a fight broke out between Geryon and Heracles (5.19.1) and Heracles drove the oxen away (3.8.13). The cattle were supposed to have come from Thessaly. Pliny then attempts to rationalise the myth, as he writes about the origin of these cattle and relates it to what life was like for the people of the time.

εἴη δ᾽ ἂν Θεσσαλικὸν τὸ γένος τῶν βοῶν τούτων, Ἰφίκλου ποτὲ τοῦ Πρωτεσιλάου πατρός: ταύτας γὰρ δὴ τὰς βοῦς Νηλεὺς ἕδνα ἐπὶ τῇ θυγατρὶ ᾔτει τοὺς μνωμένους, καὶ τούτων ἕνεκα ὁ Μελάμπους χαριζόμενος τῷ ἀδελφῷ Βίαντι ἀφίκετο ἐς τὴν Θεσσαλίαν, καὶ ἐδέθη μὲν ὑπὸ τῶν βουκόλων τοῦ Ἰφίκλου, λαμβάνει δὲ μισθὸν ἐφ᾽ οἷς αὐτῷ δεηθέντι ἐμαντεύσατο. ἐσπουδάκεσαν δὲ ἄρα οἱ τότε πλοῦτόν τινα συλλέγεσθαι τοιοῦτον, ἵππων καὶ βοῶν ἀγέλας, εἰ δὴ Νηλεύς τε γενέσθαι οἱ βοῦς ἐπεθύμησε τὰς Ἰφίκλου καὶ Ἡρακλεῖ κατὰ δόξαν τῶν ἐν Ἰβηρίᾳ βοῶν προσέταξεν Εὐρυσθεὺς ἐλάσαι τῶν Γηρυόνου βοῶν τὴν ἀγέλην. (Peri. 4.36.3)

These cattle must have been of Thessalian stock, having once belonged to Iphiclus the father of Protesilaus. Neleus demanded these cattle as bride gifts for his daughter from her suitors, and it was on their account that Melampus went to Thessaly to gratify his brother Bias. He was put in bonds by the herdsmen of Iphiclus, but received them as his reward for the prophecies which he gave to Iphiclus at his request. So it seems the men of those days made it their business to amass wealth of this kind, herds of horses and cattle, if it is the case that Nestor desired to get possession of the cattle of Iphiclus and that Eurystheus, in view of the reputation of the Iberian cattle, ordered Heracles to drive off the herd of Geryones. (Transl. by Jones)

The leading out of the oxen is also mentioned by Solinus (De mir. XXIII) in an attempt to determine the exact place of the events described. In his commentary on Virgil, Servius Honoratus (Serv. Verg. A. 8.300) cites a story already told many times.[13]

From the passages presented above, it is clear that ancient authors, beginning with Hesiod, provide a fairly similar account of the theft of Geryon’s oxen. In all the transmissions, Heracles reaches Erythea, where he fights a victorious battle with Geryon and carries out the robbery. The accounts differ in certain elements, such as the detail of the description or the addition of certain attributes, an example of which is the attire attributed to Hercules. Minor inaccuracies concern the location, which should not come as a surprise, since the events described took place, as may have been believed, at a time when history had not yet been written down and therefore the mythological places in antiquity more often existed in people’s minds than in the real world. Like other myths probably reflected the perceptions of the first people to reach these frontiers, but they have been distorted not only by the history of the land, but also by human transmission. Some depictions include additional characters, such as the shepherd Eurytion or the two-headed dog Orthos, and a description of the hero’s onward journey, which is no longer the subject of this article.

As can be seen from the information collated above, the myth has persisted since the time of Hesiod, with subsequent Greek and Roman authors reproducing certain patterns. The modifications were not significant enough to completely change the way it was read. And this is where the story of Diodorus of Sicily (1st century BC) comes in and completely changes our interpretation of the story. As a compiler and researcher of sources, the historian must have rationalised himself with the various versions of the myth of the tenth labour of Heracles and decided to interpret it in his own way, which is novel among other accounts. In the first place, the change in the perception of the figure of Geryon and the reasons for the arrival of Heracles in Iberia are noticeable. The author of the Bibliotheca Historica writes:

ἀργυρῷ δὲ καὶ χρυσῷ νομίσματι τὸ παράπαν οὐ χρῶνται, καὶ καθόλου ταῦτα εἰσάγειν εἰς τὴν νῆσον κωλύουσιν: αἰτίαν δὲ ταύτην ἐπιφέρουσιν, ὅτι τὸ παλαιὸν Ἡρακλῆς ἐστράτευσεν ἐπὶ Γηρυόνην, ὄντα Χρυσάορος μὲν υἱόν, πλεῖστον δὲ κεκτημένον ἄργυρόν τε καὶ χρυσόν. ἵν᾽ οὖν ἀνεπιβούλευτον ἔχωσι τὴν κτῆσιν, ἀνεπίμικτον ἑαυτοῖς ἐποίησαν τὸν ἐξ ἀργύρου τε καὶ χρυσοῦ πλοῦτον. Διόπερ ἀκολούθως ταύτῃ τῇ κρίσει [p. 27] κατὰ τὰς γεγενημένας πάλαι ποτὲ στρατείας παρὰ Καρχηδονίοις τοὺς μισθοὺς οὐκ ἀπεκόμιζον εἰς τὰς πατρίδας, ἀλλ᾽ ὠνούμενοι γυναῖκας καὶ οἶνον ἅπαντα τὸν μισθὸν εἰς ταῦτα κατεχορήγουν. (Diod. 5.17.4)

Silver and gold money is not used by them [the Baliares who dwelt on islands off the coast of Iberia] at all, and as a general practice its importation into the island is prevented, the reason they offer being that of old Herakles made an expedition against Geryones, who was the son of Khyrsaor (Chrysaor) and possessed both silver and gold in abundance. Consequently, in order that their possessions should consist in that against which no one would have designs, they have made wealth in gold and silver alien from themselves. Thus, to make their possessions unappealing, they made wealth in the form of silver and gold indifferent to themselves. Therefore, in keeping with this resolve, during the war expeditions they used to rational, they did not take their pay from the Carthaginians to their homeland, but bought women and wine, spending all their wages on them. (Transl. by Oldfather)

It seems that the mythological motif of the theft of cattle is associated with the wealth of the area, and these oxen were meant to be part of this wealth. Diodorus’s rationalization involves translating the symbol of wealth and prestige at the time when Haracles visited Iberia into a type of wealth closer to him in the form of precious metals, gold and silver. It also alludes to the legendary Tartessos, which was abundant in all kinds of goods. However, war and theft, of which Heracles became somewhat of a symbol, caused the impoverishment of these lands and a change in the mentality of the people living there. In fact, the legendary Tartessos was already a part of prehistory in Diodorusʼs time, and so he tries to see Iberia in a different way, as a land where men have a weakness for women and one abundant in wine. Diodorus’s description also changes the perception of the conflict itself between Heracles and Geryon. According to the historian:

[,,,] Ἡρακλῆς θεωρῶν τὸν πόνον τοῦτον μεγάλης προσδεόμενον παρασκευῆς καὶ κακοπαθείας, συνεστήσατο στόλον ἀξιόλογον καὶ πλῆθος στρατιωτῶν ἀξιόχρεων ἐπὶ ταύτην τὴν στρατείαν. Διεβεβόητο [p. 422] γὰρ κατὰ πᾶσαν τὴν οἰκουμένην ὅτι Χρυσάωρ ὁ λαβὼν ἀπὸ τοῦ πλούτου τὴν προσηγορίαν βασιλεύει μὲν ἁπάσης Ἰβηρίας, τρεῖς δ᾽ ἔχει συναγωνιστὰς υἱούς, διαφέροντας ταῖς τε ῥώμαις τῶν σώματων καὶ ταῖς ἐν τοῖς πολεμικοῖς ἀγῶσιν ἀνδραγαθίαις, πρὸς δὲ τούτοις ὅτι τῶν υἱῶν ἕκαστος μεγάλας ἔχει δυνάμεις συνεστώσας ἐξ ἐθνῶν μαχίμων: ὧν δὴ χάριν ὁ μὲν Εὐρυσθεὺς νομίζων δυσέφικτον εἶναι τὴν ἐπὶ τούτους στρατείαν, προσετετάχει τὸν προειρημένον ἆθλον. (Diod. 4.17.1–2)

And Herakles, realizing that the task called for preparation on a large scale and involved great hardships, gathered a notable armament and a multitude of soldiers as would be adequate for this expedition. For it had been noised abroad throughout all the inhabited world that Khrysaor, who received this appellation because of his wealth, was king over the whole of Iberia, and that he had three sons [i.e. the three-bodied Geryon] to fight at his side, who excelled in both strength of body and the deeds of courage which they displayed in contests of war; it was known, furthermore, that each of these sons had at his disposal great forces which were recruited from warlike tribes. It was because of these reports that Eurystheus, thinking any expedition against these men would be too difficult to succeed, had assigned the Herakles the Labour just described. (Transl. by Oldfather)

Here one can clearly see a certain inconsistency in Diodorus’s argument. On the one hand, the reason for Heracles going to Iberia was the fact that it had a large amount of silver and gold, and in this passage he reverts to the mythological narrative of being commissioned by Eurystheus to go on an expedition for a herd of cattle. Here, too, the theme concerning Geryon himself is rationalised, as it was mentioned earlier. It is clear from the story of Diodorus that Heracles had to face not so much a three-headed or triple-bodied monster, but the three sons of Chrysaor, each of whom had an army of notable men at his disposal. It was to be a kind of impossible mission. We know that, despite the difficulties, Heracles managed to complete it happily for him.

In another passage, Diodorus, in the myth of Geryon’s oxen, traces the reasons for the cult of Heracles in Iberia. He describes the course of events, which no longer describe heroic deeds, but warfare in Iberia with the aim of conquering the area. He writes about it as follows:

ὁ δ᾽ Ἡρακλῆς πολλὴν τῆς Λιβύης ἐπελθὼν παρῆλθεν ἐπὶ τὸν πρὸς Γαδείροις ὠκεανόν, καὶ στήλας ἔθετο καθ᾽ ἑκατέραν τῶν ἠπείρων. Συμπαραπλέοντος δὲ τοῦ στόλου διαβὰς εἰς τὴν Ἰβηρίαν, καὶ καταλαβὼν τοὺς Χρυσάορος υἱοὺς τρισὶ δυνάμεσι μεγάλαις κατεστρατοπεδευκότας ἐκ διαστήματος, πάντας τοὺς ἡγεμόνας ἐκ προκλήσεως ἀνελὼν καὶ τὴν Ἰβηρίαν χειρωσάμενος ἀπήλασε τὰς διωνομασμένας τῶν βοῶν ἀγέλας. Διεξιὼν δὲ τὴν τῶν Ἰβήρων χώραν, καὶ τιμηθεὶς ὑπό τινος τῶν ἐγχωρίων βασιλέως, ἀνδρὸς εὐσεβείᾳ καὶ δικαιοσύνῃ διαφέροντος, κατέλιπε μέρος τῶν βοῶν ἐν δωρεαῖς τῷ βασιλεῖ. ὁ δὲ λαβὼν ἁπάσας καθιέρωσεν Ἡρακλεῖ, καὶ κατ᾽ ἐνιαυτὸν ἐκ τούτων ἔθυεν αὐτῷ τὸν καλλιστεύοντα τῶν ταύρων: τὰς δὲ βοῦς τηρουμένας συνέβη ἱερὰς διαμεῖναι κατὰ τὴν Ἰβηρίαν μέχρι τῶν καθ᾽ ἡμᾶς καιρῶν. (Diod. 4.18.2–3)

And after Herakles had visited a large part of Libya he arrived at the ocean near Gadeira, where he set up pillars on each of the two continents. His fleet accompanied him along the coast and on it he crossed over into Iberia. And finding there the sons of Khrysaor (Chrysaor) encamped at some distance from one another with three great armies, he challenged each of the leaders to single combat and slew them all, and then after subduing Iberia he drove off the celebrated herds of cattle. He then travelled through the country of the Iberians, and as he had received honour at the hands of a certain king of the natives, a man who was distinguished for piety and righteousness, he left him some of the cattle as a gift. The king accepted them, but sacrificed them all to Heracles, and made it his practice every year to sacrifice to Heracles the handsomest bull of the herd; and it came to pass that they are still kept in Iberia, and are still sacred to Heracles down to our time. (Transl. by Oldfather)

What, then, is the rationalization of the myth of Hercules and Geryon shown by Diodorus? Firstly, Heracles is not a semigod who faces a monster alone, he is the commander of an armed expedition. There are two reasons for his expedition to Iberia; the mythological one as he was sent by Eurystheus, and the rational one, the wealth of the region. Diodorus thus alludes to the stories of Herodotus, among others, about the riches of Iberia. Chrysaor in the tale of Diodorus becomes king of all Iberia, and his three sons help him in his struggle to maintain his power and wealth. Geryon, on the other hand, is no longer a ‘triple’ monster, but one of the three brothers and leaders of Iberia; he is humanised through battle and death from the hand of Heracles. Heracles defeats Chrysaor and his sons and returns with his herds of oxen to Greece. In the story of Diodorus, the sanctification of the oxen in Iberia and the establishment of sacrifices in honour of Heracles follows. Diodorus of Sicily’s version would find continuators, for example, in the work of the 2nd century AD Marcus Junianus Justinus Frontinus (44.4), who states that Geryon was not triplicis naturae, but that there were three brothers and these tres fratres tantae concordiae extitisse, ut uno animo omnes regi viderentur, and describes the advent and spread of the cult of Heracles in Spain. Diodorus establishes a new narrative of the myth.

Late Antique writers continued to repeat the story of Geryon and Hercules, such as Ausonius (24.10) or Ammianus Marcellinus (15.9.6), who mentions that the inhabitants of Hispania claim that Hercules went there to put to death the tyrants Geryon and Tauriscus. The interpretation of Ammianus Marcellinus is significant because it presents Geryon, along with Tauriscus, as one of the saevium tyrannorum. In doing so, he leaves another already different interpretation from the one presented by Diodorus, where Geryon goes from being the son of a brave and strong leader of Iberia to being a tyrant. In the fifth century, Orosius, in his Historiarum adversus paganos libri (1.2.7), does not actually comment on the passage of Hercules through Hispania and refers to it only once, to refer, figuratively, to the Strait of Gibraltar. Something similar happens in Isidore of Seville (14.3.18), where Hercules is only a semantic addition to topographical names. In the sixth century AD, writers of the Eastern Roman Empire such as Stephanus of Byzantium, Pris of Byzantium and Priscianus of Caesarea, give almost no information about Geryon and Heracles, and their references seem more like recollections of events recounted by ancient authors.

To conclude the deliberations, it is visible hat Hesiod’s and Apollodorus’s Heracles is a hero who fights alone and is focused on bringing the oxen. Diodorus Siculus changes this optic clearly to emphasise the person of Heracles-king, the leader who brings civilisation, order and law and begins to cultivate the lands lying fallow. So, the myth about Geryon and Heracles either remained constant or evolved in two ways. There was a process of reidentification of the extremities of the oikoumene to Iberia and a process of some rationalisation of the myth.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6584-3987

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6584-3987