The Importance of Ism in al-Farabi

Before considering the core components of the words that form the title of this manuscript[1], it is crucial to discuss the important place within al-Farabi’s thought occupied by the word ism (meaning “name” or “noun”; the plural is asma). At an ontological level, al-Farabi works within the tradition of Alexandrian commentaries on Aristotle’s Peri hermeneias; thus, he begins with existents and conceptions and only then moves on to consider language and, more specifically, the act of “naming” and its outcome, the “noun”. To be more precise, one may cite Kukkonen, who has described the conception of ism maintained by this tradition in the following way: “when a quiddity is named [tasmiyya] by some kind term [for our purposes, al-ism], its referent in the mind is formally identical to the quiddity of an individual existent [al-mussama] which belongs to that natural kind (Kukkonen 2020: 55, 59, 61).”[2]

Al-Farabi also explores the nature of the name/noun from the perspective of the relation between thought and language. In his view, in perfect intellection or speculative thought, where there is an absolute identity obtaining among the three categories of (1) the being that thinks, (2) the intellect itself, and (3) the intelligible object, language is not necessary. But whenever such identity does not obtain among these three categories, we are faced with imperfect or discursive thought, and as a result, language is required in order to know something and to communicate our knowledge to others. At this point, the main issue becomes the appropriate relation between thought (maqul) and language (mantuq).

More precisely, in the first section of Kitab al-huruf (The Book of Letters), al-Farabi considers language at the level of the word, and he examines the different aspects and significations that a word may have. Most important for my argument are al-Farabi’s ideas concerning the stage at which, in using language, we reach both ‘expression’ and ‘conception’. At the level of expression, a word is distinct from sensible objects, and yet at the same time has expressive relations with said sensible objects; whereas it is at the level of conception that one finds the act of denomination itself, the creative activity proper to ‘names’ or ‘nouns’, for it is here that a name or noun becomes the very object of thought, or even, in a certain sense, the content of thought (Arnaldez 1977: 59). Once this is established, al-Farabi’s main concern becomes the relation of these two aspects (concrete and abstract) of the word – to be more precise, whether said relation is derivative (leading from concrete to abstract, or vice versa) or non-derivative.

With these two broad considerations regarding nouns/names in al-Farabi in mind, it is clear that his work on the noun/name should be taken very seriously and should not be considered a mere caprice or fantasy. In the next part of my argument, I will consider the meaning of tafsir in relation to ism.

The Meaning(s) of tafsir

In this section I shall proceed first to explore, and establish, the acceptable meaning(s) of the word tafsir as used in the title of this treatise, and then to consider the relation that this word has with the word asma and the specific meaning that results from the collocation of the two words together (as before, I shall continue to use the Arabic words until I arrive at an acceptable English equivalent). At the same time, while examining these issues I will keep in close consideration the content of the treatise itself that is the subject of this paper. This manner of approach, being indirect and heuristic, is necessary given the absence of a specific definition of this word (asma) within al-Farabi’s writings (Jihami 2002; Alon 2002).

As concerns the word tafsir, it makes most sense to begin with the literal meaning as established in standard lexica. According to Lane’s lexicon, tafsir is a substantive from a root f-s-r and effectively means “discovery, detection, revelation, development, or disclosure of a thing that was concealed or obscured” (Lane 2003: 2397). Thus, in the manuscript under discussion, what we expect to find are those Greek asma (the plural of ism) that are unclear to us as readers, along with al-Farabi’s clarification of these asma; the length of the clarification is not important, since it can be either long or short (for example, in a few words). Some further considerations are necessary. First, the core meaning of tafsir is clearly distinct from some other Arabic terms that are used to mean “definition,” “narration,” “interpretation,” “information,” “explanation,” “pronunciation,” “orthography,” “historical narrative,” “notes,” “construction,” “commentary,” and so on. Second, the core meaning of tafsir does have a relation with other Arabic words such as “translation,” “understanding,” “meaning,” “extraction,” “etymology,” “origination,” and the like, although the relation is somewhat unclear. In other words, the literal/lexical meaning of tafsir is distinct from the former group of words, whereas it shows some affinity with the latter ones.

With these lexical and methodological considerations in mind, it becomes clear that for a scholar like al-Farabi, keenly curious about both philology and philosophy, some or all of the Greek proper nouns in the document we are discussing were obscure (to take tafsir in its literal/lexical meaning). However, the document is more complex than a simple explanation of the obscure. For in fact, in it, we find that al-Farabi’s remarks make some of these words even more obscure or mysterious: for example, his metaphorical semantics of color, when he adduces the color of heaven for Porphyry, blue for Glaucon, and gold for Chrysaorios, raises more questions and doubts.

It is clear, then, that the “lexical” meaning of tafsir is necessary but not sufficient; one must further explore the semantic range of this word, in order to understand what is at stake in this document. It is necessary to broaden the field of inquiry, and I will therefore explore the use of the word in classical and medieval Arabic literature before and during al-Farabi’s era (the tenth century), in order to establish a more nuanced general perception of the word tafsir; and then I will apply these results to our discussion of the document in question, in order to understand fully the appropriate implications that the word has in its title. It remains something of a difficulty that, although al-Farabi worked within a tradition of medieval philosophy and formal logic and within this methodological tradition the “definition” had a very specific place, nonetheless there is no explicit definition of tafsir in our text. How can we resolve this problem? Since al-Farabi was attentive to the friendly interplay of philosophy and philology, and since the word tafsir occurs in classical and medieval Arabic literature, it is justifiable to refer to said literature so that we may discover some pertinent clues and apply them to al-Farabi and to the text we are discussing.

By reviewing the classical volumes of the Geschichte des Arabischens Schriftums (GAS) [2, 8, 9], we can see that the word tafsir as a specific or general term is used in the titles of numerous manuscripts and is applied to many different topics, such as: the Quran; tradition; dreams; words; poems; and “names” or “nouns” (the last two words can be considered the equivalents of the Arabic word asma). While it is true that some of the relevant Arabic manuscripts are no longer extant and only their titles are known, others have been preserved and by reviewing their contents we can reach the conclusion that tafsir has a “minimal shared meaning”, which, in turn, becomes more detailed and, as it were, “technical” when the word is employed in the specific title of each given work. For example, tafsir appears in collocation with both “Quran” and “names/nouns”; but for a speaker of Arabic, the sense of tafsir in each case is slightly different. Confronted with such a state of affairs, we can assert that it is the content of the manuscript itself, in conjunction with the usage and habits of individual writers addressing specific subjects, which allows us to determine the appropriate technical meaning of tafsir in the title of a given extant manuscript (Dodge 1970: 909, 925).

A further consideration: within classical and medieval Arabic literature, there is a greater number of manuscripts that have “names/nouns” (asma) in their titles in relation to various topics (such as God; the Prophet of Islam; Poets; Things; Swords; Camels; Wars; Days; Winds; Clouds; Horse; Lion; Places; and Tribes) than there are manuscripts that have the collocation of tafsir asma in relation to human beings in their titles. How can we explain this?

In order to gain insight into al-Farabi’s concern with particular human names (say, in the form of tafsir asma [Greek] hukama – a title which itself does not exist but which I propose for the sake of argument), it seems best to narrow down our search even further and to examine in classical and medieval Arabic literature those manuscripts that have in their titles “tasfir asma of particular humans”. Within such parameters, two books, both of which discuss poets, stand out, namely: almabhaj fi tafsir asma shoara al-hamasah by Ibn Ginni (GAS 1975: 69); and tafsir asma shoara by abu Umar az-Zahid (GAS 1975: 100). Thus, we have two books whose titles proclaim them to be “tafsir asma” of particular humans – in this case, Arab poets. In the first, Ibn Ginni’s Delight in the Tasfir of the Names of the [Arabic] Epic Poets, the author, who was an outstanding literary scholar with an interest in the etymology of Arabic names of persons, writes clearly about his conception of “tafsir asma,” and says that it involves analysis of the “conditions of these proper names, the way they have been made, how many forms they have found, and into how many forms they have been divided.”[3] Thus, to judge by his wording, and in the context of medieval Arabic literature, Ibn Ginni understands four interrelated things as being involved in the “tafsir” of the personal names of the Arabic epic poets. First, he considers poets’ names as “proper names”, which in Arabic are called “a’lam”. It is clear, therefore, that he wants to discuss a specific class of names/nouns and he recognizes them as such in contrast to other grammatical classes of the noun. Next, he considers the way such names are built and shaped. Then he considers how the words took on different forms according to Arabic syntax and into how many forms they have been divided. In contrast, regarding the work tafsir asma shoara by abu Umar az-Zahid, we only possess the title and, while we can suppose that it was limited to the discussion of the names of Arab poets, of the contents and the approach of the author we do not have any explicit information.

On the whole, then, it appears that the use of “tafsir asma” in relation to proper names that we find in other classical and medieval Arabic manuscripts differs from what al-Farabi, as a philosopher-philologist, undertakes in the manuscript under discussion, insofar as this manuscript discusses particular non-Arabic personal names, the majority of which belong to Greek scholars. We are not dealing with an Arab scholar discussing the nature of names within his own tradition, but rather with a scholar who is discussing names in a language (Greek) of which he is not a native speaker, even though it can be assumed that he should have had some knowledge of this language. As a result, the use, as points of comparison, of the titles of manuscripts that work within the tradition of medieval Arabic literature offers only limited, and not entirely clear, results.

We can make further progress, however, if we consider those writings of al-Farabi that give some hints concerning his understanding of the proper names of classical Greek scholars and show they way that he deals with them. In this regard, I believe that we should take into account his treatise entitled The Philosophy of Plato, Its Parts, the Ranks of Order of its Parts from the Beginning to the Ends. In this text, al-Farabi intends to present a summary narrative of Plato’s philosophy according to the order and titles of the dialogues. It is noteworthy, however, that even before describing the content of a given dialogue, al-Farabi considers the meaning of the dialogues’ titles, which, as is well known, are in many cases the proper names of Greek individuals (for instance, Euthyphro, Phaedo, or Phaedrus, and even other Greek philosophers, such as Parmenides and Protagoras). Therefore, in the next section of the paper I want to explore al-Farabi’s treatment of the Greek personal names that appear as the titles of Plato’s dialogues, in order to find a point of comparison, which may act as a bridge that will lead us to a correct understanding of the sense, he would attribute to a title such as tasfir asma “of some Greek scholars”.

Greek Proper Names in the Titles of Plato’s Dialogues

Given that the foregoing approaches offer only partial solutions to the question of interpreting the title of this work, I want to consider heuristically, as a comparative document, al-Farabi’s treatise The Philosophy of Plato, Its Parts, the Ranks of Order of its Parts from the Beginning to the Ends. In this work, al-Farabi discusses the personal names that constitute the titles of many of Plato’s dialogues. By examining this work, we can come to an understanding of what al-Farabi intended the word “tafsir” to mean, and then we can apply these results to better understand the title of the work, which is the subject of my paper, the tafsir asma hukama.

Through an examination of al-Farabi’s treatise on Plato, we can explore the way that he understood those dialogues that contain Greek proper names in their titles, with specific attention to the different words that al-Farabi uses or those words which are philologically restored and attributed to him by his two major Arabic editors, Badawi and Mahdi (Badawi 1974: 5–27; Mahdi 1962: 53–70). In this way, I hope to be able to sketch a picture of al-Farabi’s philological-philosophical practices – importantly, without judging whether the Arabic equivalents he proposed for Greek personal names are in fact right or wrong according to modern philological and linguistic research. For al-Farabi, the Greek names were associated with the following Arabic words (the underlined words indicate how al-Farabi glosses the relationship, as he sees it, between the Greek and the Arabic words; I will discuss these underlined words further below): Alcibiades, “namely model”; Theaetetus, “meaning voluntary”; Philebus, “meaning beloved”; Protagoras, “meaning the carrier or maker of bricks”; Meno, “meaning fixed”; Gorgias, “meaning service”; Parmenides, “meaning compassion”; Hipparchus, “observation”; Theages, “namely experience”; Laches, “preparation”; Phaedrus, “and the meaning of this word in Arabic is shining or illuminating”; and Critias, “meaning separating out the truths.”[4]

As we can see, al-Farabi’s style is not uniform. Sometimes he does not use any extra words for describing the way in which he is interpreting the proper noun; but when he does, he uses two Arabic terms which can be translated in English as “namely” or “meaning”. What do these terms mean, precisely? Is it that he wants to indicate, in some cases, that a Greek noun has a meaning similar to an Arabic word, and that, in other cases there is homonymy? Perhaps with the word “namely” he wants to say something specific about the Greek proper nouns themselves? To reach a possible answer to these questions, we need to further clarify the meaning of ism “name/noun” in al-Farabi, since the meaning of tafsir is dependent upon the meaning of asma (“names/nouns”, in the plural). Therefore, we will continue with further examination of asma.

asma: Names/Nouns

Now that we have understood the content of the treatise tafsir asma al-hukama, we may safely conclude that asma (the plural form of ism from the root s-m-a), the second and core word of the title of the treatise, indicates in this context a specific and limited category constituted of “proper names” (which happen to be, in this case, Greek proper names). Now, it is appropriate to note that for such a category there are other more precise technical terms in Arabic, such as ism a’lam or simply a’lam; and one might have expected the title to have used one of said terms. However, we can probably assume that the author of the treatise found that it was not useful or necessary to specify the categorization with these terms (ism a’lam or a’lam), perhaps because he was influenced by Aristotle or Thrax, given that for Aristotle the dichotomy of the noun into common nouns and proper nouns is not salient, and for Thrax both common nouns and proper nouns come under the general title of the noun in any case (Eichler 1995: 385).

Moreover, al-Farabi was consistently interested with, and concerned by, ism at a philological and philosophical level, as can be seen in the titles of other treatises of his, such as: “Names” of the Sects in Philosophy; From the “Names” of Scholars who are Philosophy Masters; “Names” of the First Existent; “Names” of the Categories; The “Names” of Sciences; and “Names” that are transformed into Philosophical Meanings. In addition, we can find other, scattered theoretical discussions about “noun/name” in other works, such as Kitab al-Huruf (Book of Letters); Kitab al-Alfaz al-Musta’mal fi l-Mantiq (Book of Utterances Employed in Logic); Kitāb al’Ibārah (commentary on De Interpretatione/Peri hermeneias); and Kitab al-madkhal (Isagoge). From this catalogue we may reasonably expect to read al-Farabi’s considerations and explorations concerning ism in those writings which are largely dedicated to logic.

With all this in mind, in order to understand better and translate satisfactorily the use of ism in the title of the work under discussion, it seems best to consider al-Farabi’s commentary on Aristotle’s De interpretatione/Peri hermeneias, since the content of this work is not merely logical but linguistic as well. Now, within the Arabic literary tradition both before and during the time of al-Farabi, the word ism may be translated either as name or as noun (Zimmerman 1988: XXV); but there is a nuance that must be taken into consideration if we do not want to regard al-Farabi’s commentary as a mere grammatical or lexical inquiry. Epistemologically, when there is some kind of relevancy between a kind of knowledge and its objects, it is possible to know and to communicate our knowledge about these objects by means of a specific rationale or philosophy. And, in order to communicate our knowledge, we need to signify the nature of these things by a name, and in this way a name comes into existence. Grammatically, however, when a grammarian examines the final result of this process, he or she describes it as a “noun”. In other words, the Arabic grammarians in the classical and medieval periods were mostly interested in proper nouns/personal names (a’lam or ism a’lam) insofar as they were agnomina, nicknames, pseudonyms, or noms de plume, or insofar as they referred to lineage or family relationships (Versteegh 2008: 717); on the other hand, they were not primarily concerned with the rationale and the process of naming as such, or with its product, namely proper nouns/personal names. And yet, the dividing line between these categories is not entirely definitive or fixed; and therefore, when al-Farabi as philologist/philosopher writes asma in the title of a manuscript, he means “nouns” that are the product of the “naming” process. As a result, the word asma contains both meanings at the same time (“noun” and “name”).

At this point, we can now demonstrate the reasons for al-Farabi’s interest and concern with personal names-nouns. He considers ism to be a category that can be explored from both philological and philosophical perspectives; and these two perspectives are in interplay. By philology in its Greek – not Arabic branch that includes grammar and lexicography (Makdisi 1990: 120) – I want to say that ism/ noun is distinct from kaleme/word that as a broad category has a connection with speaking because it goes together with the act of speaking or logos.

At the same time, however, al-Farabi does not mean to distinguish ism (“noun”) from the verb, because the latter is a “grammatical” category that is defined in relation to time and is dependent upon a subject or agent. When I speak of a philosophical perspective, I mean that when there is a non-identification between knowledge and its object, in order to bring these objects into presence, human beings appeal to language, and as a result, they “name” them. Lastly, if we take the perspective of logic, that which is named will be considered “subject” and some appropriate “predicate” will be attributed to it, and after that a proposition can be made from these two elements.

Thus, when there is a gap between the mind and things, with no overlapping, it is necessary to have a “noun” as a mediator, in order to make such a connection, by “naming” the things (Eichler 1995: 368). Therefore, for most classical and medieval thinkers, names are essential, for they are necessary to recognize things. Working within this tradition, al-Farabi, as a scholar of names, seeks the content of the names/nouns of a few selected Greek wise men (two other are, admittedly, not human), who are outstanding in different branches of wisdom. And we can see that he is interested both in the “referents” and in the “meanings” of these fourteen Greek names/nouns: in other words, al-Farabi connects two aspects of names/nouns, their appellative or referential dimension (that is, the historical person to whom they refer) and their semantic dimension (the meanings of the lexical roots in the names), and in a certain way he integrates them. To be more precise, al-Farabi is not merely considering their referential aspect, for if he were, he would not need to research and present the meanings of the names (as in “Philebus, meaning “beloved”); and on the other hand, he is not merely researching the semantic dimension, for if he were, he would not be interested in seeking out their proper spelling and form, insofar as they are exotic non-Arabic nouns.

With all of this in mind, we can begin to sketch a picture of what al-Farabi means by asma, names/nouns. I have already mentioned that al-Farabi was not inclined to draw a distinction between common and proper nouns. And yet, there are some places where he speaks of such a division, and when we consider the way he defines this division, we see that it is somewhat different from the traditional grammatical division. As a result, we need to understand his specific conception of this distinction, because it can be useful for interpreting the treatise tasfir asma al-hukama. A name/noun, per se, as a single word, signifies a meaning that can be understood in itself, and by itself may be divided into common and proper kinds, whereby a common noun refers to a genus that some referents belong to, whereas a proper noun is a title that signifies the specific identity of a referent (Jihami 2002: 42–43).

In light of these considerations, we may speak of the “proper” noun in al-Farabi and then consider the resources he had at hand for glossing the selected Greek proper nouns/names in the treatise under discussion. To judge from the content of the treatise itself, it is clear that the author provides information regarding the proper names of the philosophers taken from different sources, such as: the accounts of other scholars; the idea of a scholar’s teacher; the fact that a scholar belonged to a specific circle; particular things for which a scholar was famous; informal reports; the semantics of color as present in the lexical roots of names; and the like. All of these interests and sources of information make this treatise different from the work of etymologists proper, or from lexicographers, logicians, and nomenclature experts; and at the same time, they bring the treatise closer to the concerns of rhetoricians, humanists, encyclopedists, folk-etymologists, and the like.

The Meaning of the Hukama or the Wise

The title of this treatise indicates that it will consider the names/nouns of some selected wise Greek scholars. It is noteworthy, however, that al-Farabi, in his treatise Attainment of Happiness, presents a similar analysis of four words, but this time common rather than proper nouns, namely “Prince,” “Philosopher,” “Legislator,” and “Imam” (Mahdi 2001: 189–191). We can assume, therefore, that the selection of the Greek names in our treatise is determined by their referring to individuals remarkable for the shared quality of wisdom (with the caveat, of course, that two of the individuals – Hermes/ هرمس and Asclepios/ اسقلبیوس – were not human beings but rather a god and a demi-god, respectively.

It is important, therefore, to consider also al-Farabi’s definition of this shared quality, wisdom. Elsewhere, al-Farabi has provided a definition of the wise person that can be applied to what is meant in the treatise we are discussing here: “he who is extremely competent in an art is said to be wise in that art. Similarly, a man with penetrating practical judgment and acumen may be called wise in the thing regarding which he has practical judgment. However, wisdom without qualification is this science (i.e. philosophy) and the mastering of it.” (Alon 2002, vol. 1: 90–91; vol. 2: 760). If we accept this definition, we can see in this indexical minimal onomasticon a list of proper names of Greek men (with the two exceptions listed above) who were outstanding in theoretical, practical, and technical knowledge: Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Porphyry, Chrysaorios, and Glaucon in philosophy or theoretical knowledge; Galen, Hippocrates, Rufus, and Asclepiades in medicine or technical knowledge; Plato and Themistius in rhetoric or practical knowledge; and Aristotle and Alexander in ethics or practical knowledge.

tafsir asma as a Mixed Contextual Treatment

With regard to this classification, when we read the manuscript under discussion, we see that different practices come under the general concept of tafsir. Hitherto I have retained this word in Arabic instead of translating it into English, but now I want to offer proposals for how to interpret it in specific contexts:

A. Epithet Resulting from Reputation. Within this context, we have for example the name of Plato/ افلاطون as “the sincere eloquent one”. (Pace Rosenthal (1942: 73), I believe that “sincere eloquence” and not “broadness of shoulders” has more relevance with a kind of practical wisdom – of course, if we take broadness in its usual sense and not in a metaphorical one.) Then there is Aristotle /ارسطاطالیس as “the one of perfect virtue”; Galen/ جالینوسas “the one working wonders”; Hippocrates/ ابقراطas “the one holding fast health”; Socrates/ سقراطas “the one adorned with wisdom”; Rufus/ روفس “the mine of wisdom”; Alexander/ الاسکندرas “the very brave one”; and Themistius/ ثامسطیوس as “the one of elegant expression”. These short identifications can usually be considered the conceptions that the community held regarding certain ancient Greek wise men and which, in the course of time, became their particular epithets. These explanations, then, fall under one meaning of tafsir as understood by the author of this treatise.

B. Metaphorical Semantics of Colors. It is worth noting, in passing, that both Greek chroma and Latin color have, at root, a semantic connection with ‘surface’ or ‘covering’, whereas al-Farabi is interested in exploring what lies under the surface of names. It is also important to note, however, that when al-Farabi explores the significance and semantics of color, he is employing conceptions of color that are different from our contemporary ones. In this regard, for al-Farabi color is a “relational notion” that has connections with multiple different ideas, both abstract and concrete, which are in relation with each other and which, on the whole, constitute the meaning of a color term; for us, on the other hand, colors generally denote a limited and specific field. Therefore, in this document colors are not used in our simpler, modern sense; rather, they function as metaphors and, in a certain way, they shift between chromatic and achromatic aspects. This renders our understanding of the use of colors in this document, as in other contemporary documents, challenging and potentially ambiguous (Clarke 2017: 10, 21).

Within this group of explanations, we find the names: Porphyry/ فورفوریوسas the “color of the heaven”[5]; Glaucon/ اغلوقنas “the blue one” (this is, in fact, the correct etymology according to modern linguistics); and Chrysaor/ Chrysaorios/ خروساوریا as “the color of gold.” This last etymology is only semi-complete, because the first part of the name (χρυσο-) means “gold,” but in the document under discussion there is no trace of its second part (αορ-, meaning “sword”).[6] Perhaps the author considered the “sword” element not suitable in the name of a wise man! In addition, it is only with regard to this name that the author uses the phrase “excellent reasoning” to describe the name’s structure/significance (sama).[7] From this we can see further evidence that the author did not have an exclusively physical conception of color, and therefore we as readers should not expect a purely physical, modern conception of color with regard to the other names, either.

C. Real or Correct Etymologies. Among these proper names of particular Greek wise men, two of them are etymologized (ishtiqaq is the Arabic term) in a manner that is substantially “correct”: one is Glaukon/ اغلوقن, which we have seen above, and for which al-Farabi suggests the “blue one” (though in ancient Greek it may also refer to light green, grey, or yellow); the other is Asclepiades اسقلبیادس /. Regarding the latter, the author of our document writes: “the one derived (al-mushtiq) from the divine power”. This etymology is correct, if only partially, since the anthroponym Asclepiades does in fact derive from the theonym Asclepios (meaning “the one who negates dryness”). In other words, the god of medicine possesses a certain power and the god’s name refers to the negation of dryness (a term for kinds of illness among the Greeks), and Asclepiades designates a human being, specifically a physician, who can heal this dryness because he has derived his name, and with it his healing power, from the god. Therefore, the name has a true etymological derivation from a divinity (recall that etymon in Greek means “the true sense of a word”). It is curious, and important to note, that in both the ancient Greek context and in al-Farabi, etymology is not necessarily the study of the historical origin or development of a word (or a lexical root), as is the case in modern philology and linguistics. That said, the etymology presented in the document under discussion – the physician has the nature of the god of medicine who functions as the principle (arche) of his craft, and therefore the physician has a name deriving from that god – is substantially correct: his name is, in fact, “derived from a divine power.”[8]

Conclusion

To sum up my account, we may assert, first, that the collocation tafsir asma in the manuscript under discussion indicates an explanation of the reputation that certain Greek wise men acquired in their lifetime (for example, Galen as “the one working wonders”) which then came to serve as the epithet for that individual. In addition to this basic meaning, in our text tafsir asma can also be employed to describe the metaphorical interpretation of connotations associated with colors, all of which, in this context, have some relationship with wisdom and its different shades of meaning among non-Arab cultures. Lastly, and to the least degree, tafsir asma may refer to the real and true etymology (al-Ishtiqaq), as the correct meaning of the personal proper names, according to the standards and practices of classical and medieval Arabic scholarship.

Overall, we may say that, in this text, al-Farabi (or whoever its author may be), as a philosopher and philologist wished to present his reader with holistic but concise information regarding the identity of certain Greek wise men and the meanings of their names. This information also contains elements that are pragmatic, rhetorical, and even emotional, and can be used to distinguish these various “exotic” (non-Arabic) proper nouns, even though all of them share, in some way or another, in the laudable quality of “wisdom” – according to the broad meaning of that term as we have seen above in al-Farabi’s definition.

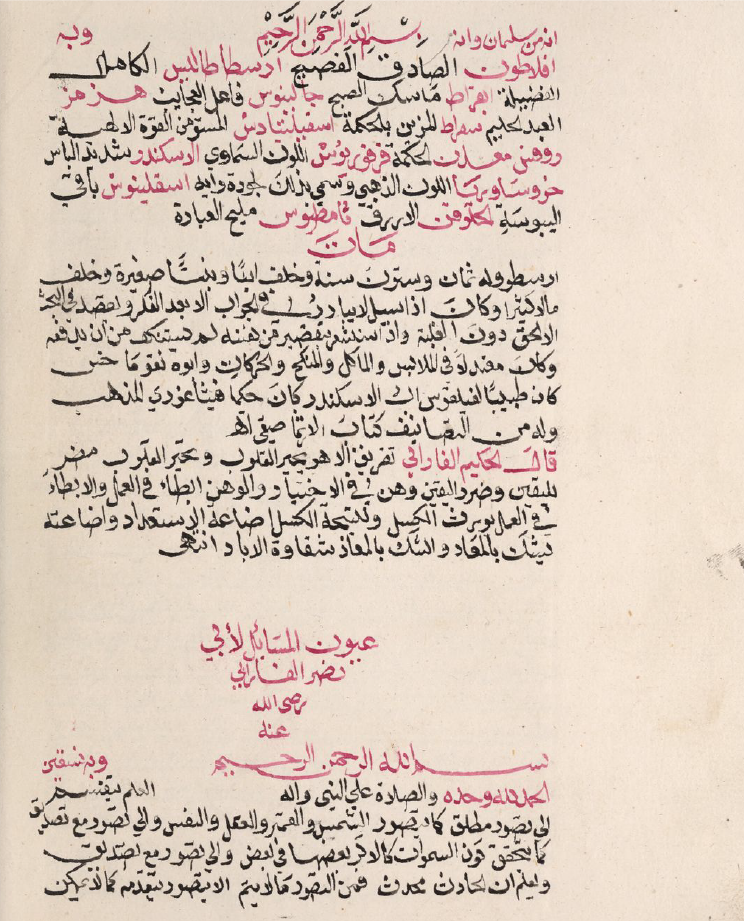

Figure 1. [Risālah al-Ighrīḍīyah ... etc.]. Ms. codex. Majmūʻah volume. Islamic Manuscripts, Garrett

no. 464H. Princeton University

e-mail: younesie_7@yahoo.com