Available online at: https://doi.org/10.18778/1898-6773.87.2.07

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2922-4695

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2922-4695

Department of Anthropology, University of Kolkata, India

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6648-4875

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6648-4875

Biological Anthropology Unit, Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, India

ABSTRACT: Menopausal transition and post-menopausal periods can have short-term and long- term effects on mid-life health of women. The short-term effects include the possibility of experiencing of menopausal symptoms, while the long-term effects include cardiovascular diseases (CVD) risk. The occurrence of menopausal symptoms varies widely within and between populations. Studies indicate that the frequency and severity of menopausal symptoms are linked to CVD risk factors, but the existing literature is divergent and somewhat limited. Thus, women belonging to different populations are likely to be at a different risk of CVD, but the exact physiological mechanism behind this relationship remains unclear. The present narrative review aimed to synthesize the available evidence of menopausal symptoms in association with various conventional CVD risk factors such as blood pressure, total cholesterol and blood glucose levels and obesity, as well as to determine the potential link between these two processes. We undertook a rigorous data base search to identify, examine, and critically assess the existing literature on the associations between menopausal symptoms and CVD risk factors. We applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to filter the retrieved articles and classified the literature into eight major categories. The risk of CVD is higher among women who experience vasomotor, psychological, and urogenital symptoms compared to those who do not experience these symptoms. Our review indicates that menopausal symptoms can be used as markers in assessing CVD risk factors during midlife. Thus there is a need for larger-scale research to support these findings and identify the potential mediators that are controlling this association.

KEY WORDS: cardiovascular disease, menopausal symptoms, vasomotor symptoms, psychological symptoms, postmenopausal women, insulin resistance, lipid profile, blood pressure level.

An estimated 1.5 million women pass through the menopausal transition every year (Santoro et al. 2015). The phases of menopausal transition and postmenopause have profound effects on women’s mid-life health. The period between perimenopausal and postmenopausal stages involves a biopsychosocial process, where the majority of women experience some short-term and long-term physiological changes. The short-term changes may include experiencing of vasomotor, urogenital, and psychological symptoms, decreased libido, insomnia, fatigue, as well as joint pain (Dennersteinet et al. 2000; Sherman et al. 2005; Cohen et al. 2006). It has been argued that these short-term changes are related to the decline in the levels of estrogen and progesterone, one of the most important hormones in female’s physiology.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) continues to be the leading cause of mortality for women (Townsend et al. 2016). Menopausal transition is identified as a significant risk factor of CVD, which increases independently of the effects related to aging (Matthews et al. 2017; El Khoudary et al. 2020). The decline in the estrogen levels during and following the menopausal transition has been reported to be associated with menopausal symptoms and CVD risk factors (Carr et al. 2003). Studies show that the alternations in the estrogen levels not only affects glucose and insulin metabolism, but also changes body fat distribution, introduces dyslipidemia, coagulation, fibrinolysis, and vascular endothelial dysfunction (Carr 2003; Cakmak et al. 2015; Son et al. 2015).

Some researchers have posited that the frequency and severity of menopausal symptoms are linked to CVD risk factors (Gast et al. 2008, 2011; Gallicchio et al. 2010; Szmuilowicz et al. 2011; Kagitani et al. 2014; Thurston 2018) while several studies demonstrated the relationship between the frequency and severity of these symptoms with subclinical CVD, including increased intima media thickness (Thurston et al. 2012), aortic calcification (Thurston et al. 2008), and endothelial dysfunction (Bechlioulis et al. 2010). A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Muka et al. (2016), which included 213,976 middle aged women revealed a significant association of vasomotor, psychological, and urogenital symptoms with an elevated risk of CVD. Although several studies have documented the association between menopausal symptoms and CVD, the resulting findings have not been consistent (Svartberg et al. 2009; Tuomikoski and Peltonen 2017). Menopausal symptoms vary greatly across populations so women belonging to different population groups are likely to be at a differential risk of CVD, thus the exact physiological mechanism linking menopausal symptoms and CVD risk factors remain unclear (Gast et al. 2008).

In the present review, we aimed to synthesize all available evidence regarding the association between menopausal symptoms (e.g., vasomotor, urogenital, and psychosocial) and various conventional CVD risk factors, such as blood pressure, total cholesterol and total glucose levels, and obesity, and to determine the potential link between these two events.

In this review, we undertook a rigorous data base search in order to identify, examine, and critically assess the studies conducted on associations between menopausal symptoms and CVD risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, serum total cholesterol, and central obesity. The search was conducted using the Google search engine, PubMed, and Medline websites during the period of May 2023 to January 2024 using specific keywords: “Menopause”, “Cardiovascular disease”, “Vasomotor symptoms”, “Menopausal Symptoms”, “Psychological symptoms”, “Hypertension”, “Estrogen”, “Lipid” etc. While performing the search we included some specific combinations of terms, such as vasomotor symptoms and CVD, psychological symptoms and CVD, hot flush and hypertension, the physiology of vasomotor symptoms, the frequency and severity of VMS among midlife women, the severity of menopausal symptoms and cardiovascular risk factors. Initially, we categorized the published literature based on studies that independently linked VMS, psychological, and urogenital symptoms to CVD risk factors. Subsequently, we thoroughly investigated the association between these symptoms and manifestations of CVD risk factors. Finally, we attempted to identify and discuss the research gaps within the Indian context.

We used the following inclusion and exclusion criteria to filter the retrieved articles. Articles published in peer-review journals or by any reputed organization related to the topic of women’s midlife health and/or on perimenopausal and postmenopausal women, based on both field based, and hospital based studies and observational and interventional studies that reported an association between menopausal symptoms and CVD were considered in this study. A few systematic reviews, meta-analysis, pooled analysis, cohort studies were also included in this review. Only articles that have been published or translated into English were considered in this review, spanning between January 2000 and December 2023.

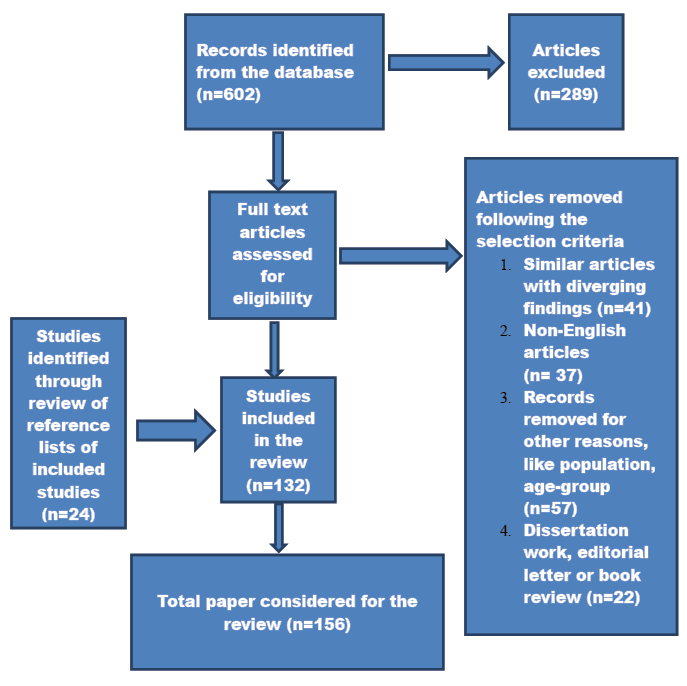

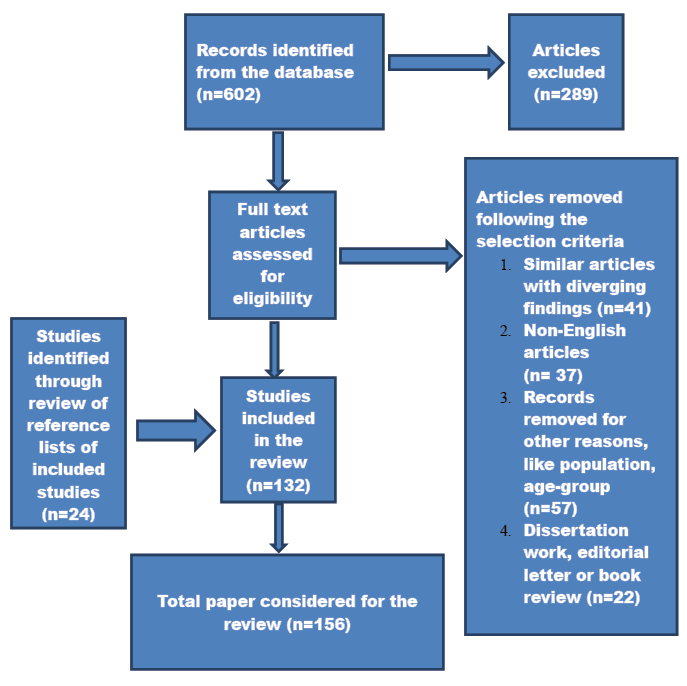

602 articles were retrieved following the article-retrieval protocol described above. A predesigned data extraction form (Franco et al. 2015) was used to extract pertinent information from each eligible study. This incorporated information on the sample size, baseline population, study design, age at baseline, duration of follow-up (for cohort studies), degree of adjustments for confounders (like age, sex, smoking status, ethnicity and BMI), and the outcome and limitations of the study. 313 articles were retrieved following this process. The authors sorted the selected articles to eliminate similar studies with diverging results and conclusions, non-English literatures, and editorial letters or book reviews. We finally considered156 full length articles exploring the physiology of menopausal symptoms and its association with CVD risk factors. When multiple publications by the same author were considered, we incorporated the most recent publications of that author.

We classified the literature after completion of the article retrieval process. The full text articles were divided into eight major categories: (1) 29 articles on the severity and frequency of menopausal symptoms, (2) 15 on the physiology of vasomotor symptoms, (3) 12 on the physiology of urogenital symptoms, (4) 18 on the psychological symptoms of menopause, (5) 33 on the association between VMS and CVD, (6) 23 on association between psychological symptoms and CVD, (7) 9 on association between urogenital symptoms and CVD, and (8) 17 articles on the association between menopause and CVD risk factors. We examined the reference lists of the selected articles to identify the potential articles for cross-referencing and later cited in this review. We did not find any Indian study examining the association between menopausal symptoms and CVD risk factors. However, we included in our study some Indian studies that only explored the severity and frequency of menopausal symptoms. A flowchart depicting the article retrieval process is presented below (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Flowchart of narrative review of literature

Vasomotor symptoms (VMS) are one of the most prevalent symptoms experienced by 80 % women worldwide during the menopausal transition. The symptoms include hot flushes and night sweats; the severity and duration of these symptoms also vary across populations (Franco et al. 2015). Previous studies have indicated that the median duration of VMS is 7.4 years, while other studies have reported much longer duration (Avis et al. 2015). Hot flush refers to a sudden sensation of heat and sweating, most notably on the upper part of the body, while night sweats are the manifestation of heat during nighttime. Although estrogen has been used to treat vasomotor symptoms, the exact mechanism through which estrogen induces this phenomenon inside the body has not been investigated. VMS originates from the changes in the neurotransmitters located at the brain. It brings instability in the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center and causes decrease in estrogen levels. Hot flushes, a type of VMS result from a reduced thermoneutral zone (Freedman and Krell 1999). This reduction seems to be linked directly to the elevated norepinephrine (NE) levels in the central nervous system, partly through alpha 2 adrenergic receptors reducing the width of the thermoneutral zone (Avis et al. 2015; Thurston 2018). Estrogen modulates the alpha 2 adrenergic receptors (Thurston 2018). The fluctuation in estrogen levels affects the alpha 2 receptors and lead to increased NE levels, which ultimately cause inappropriate heat loss mechanisms and increase the likelihood of VMS (Freedman 2005).

A growing body of evidence suggests that women who reported VMS are likely to have higher cholesterol, triglyceride, low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) and systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels, a higher body mass index (BMI), and insulin resistance (Gast et al. 2008; Thurston et al. 2012; Cagnacci et al. 2015; Franco et al. 2015), although the reported results are not consistent (Gallicchio et al. 2010; Dam et al. 2020). Studies also have demonstrated the association of VMS with hypertension (Gast et al. 2008; Jackson et al. 2016), insulin resistance (Gray et al. 2018), adverse lipid profiles (Gast et al. 2008), poor endothelial dysfunction (Thurston et al. 2008; Bechlioulis et al. 2010), high proinflammatory profile (Huang et al. 2017), and incidences of subclinical CVD (Ȍzkaya et al. 2011; Thurston et al. 2016). For example, two epidemiological studies conducted among middle aged women in Japan (Kagitani et al. 2014) and the Netherlands (Gast et al. 2008) found that, compared to women without VMS, women with VMS are more likely to have a higher CVD risk factor, including high blood pressure and total cholesterol levels. Similarly, four cohort studies, some of which included American women, revealed increased risk factors of CVD (high blood pressure and total cholesterol levels) for those who reported a higher incidence of VMS compared to women who did not (Gastet et al. 2008; Kagitaniet et al. 2014; Franco et al. 2015). Some studies suggested that percent body fat and VMS are positively correlated (Thurston et al. 2013; Da Fonseca et al. 2013; Herber-Gast et al. 2013; Gallichio et al. 2014). For example, a study conducted by Cagnacci et al. (2015) showed that women who experienced hot flushes had a higher body fat percentage and increase in the severity of VMS was associated with higher levels of body fat. Similarly, a recent study conducted among 2533 women aged between 42 and 52 years showed that lean body mass is inversely associated with the incidence of VMS (Woods et al. 2020). The underlying mechanism of this association is not yet clear due to the incomplete understanding of the physiology of VMS. Some scholars argue that the sympathetic overactivity that exists in both VMS and metabolic syndrome is a common pathway linking these two processes (Schlaich et al. 2015; Gava et al. 2019). Earlier studies have hypothesized that body fat is protective against VMS due to the process of peripheral aromatization of androgens to estrogen in adipose tissues (Kershaw et al. 2004). The ‘thermoregulatory model’ suggests that adiposity inhibits heat dissipation and raises the core body temperature, thereby increasing the incidence of VMS (Duffy et al. 2013). On the contrary, a recent 20-year of follow-up study by Dam et al. (2020) reported no significant association between vasomotor symptoms and CVD, coronary heart disease, or cerebrovascular disease. However, the same study reported that women who had night sweats are at 18% increased risk of CVD compared to those who did not, although this increase was statistically nonsignificant. A study among perimenopausal women conducted by Thurston et al. (2012) showed that higher VMS is associated with a derangement of the lipid profile. Gast et al. (2008, 2010) have replicated findings of positive associations between VMS, body fat, total cholesterol, systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels from population-based studies conducted in the Netherlands and Sweden. Gallicchio et al. (2010) observed a non-significant association between hot flush and blood pressure level after adjustment for confounders such as smoking, alcohol consumption, ethnicity and the use of hypertensive medicines. Similarly, after controlling the confounders like educational attainment, smoking status, and BMI, Gast et al. (2008) reported no significant association between blood pressure level and hot flushes.

A couple of studies reported that severity of VMS, rather than frequency, is associated with an increased risk of CVD (Muka et al. 2016 and Zhu et al. 2020). The severity of menopausal symptoms among postmenopausal women, as evaluated by the Green Climacteric Scale, is related to endocrine and metabolic modifications, possibly leading to an increased risk of CVD (Cagnacci et al. 2011, 2012). In these studies, hot flush and night sweats were combined thus, it was not possible to evaluate the impact of each symptom independently. A cross-sectional study found night sweats rather than hot flush is associated with an elevated risk of coronary heart disease; the association persisted even after controlling for the traditional CVD risk factors like BMI, blood pressure, and total cholesterol levels (Gast et al. 2011). Some studies have reported that hot flushes and night sweats have different etiologies for CVD, but the exact mechanism is not well understood (Hitchcock et al. 2012; Herber-Gast et al. 2013). Some evidence indicates that the combined effect of hot flush and night sweats on the risk of CVD was higher than the independent effect of each symptom (Zhu et al. 2020).

Studies suggest that age of occurrence of VMS may influence the association between VMS and CVD risk factors (Szmuilowicz et al. 2011; Thurston et al. 2016). It has been hypothesized that the predictive value of vasomotor symptoms for CVD risk factors may vary with the onset of VMS at different stages of menopause (Szmuilowicz et al. 2011; Thurston et al. 2016). For example, a study of Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation reported that women who experienced menopausal symptoms at an early phase of their lives (before 42) had endothelial dysfunction and elevated CVD related mortality compared to those who experienced menopausal symptoms later in life. The association persisted even after the adjustment for BMI, smoking status, and age at menopause (Thurston et al. 2016). On the contrary, the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study (WHI-OS) conducted in the New York City demonstrates that although early onset of VMS is not associated with CVD risk factors, the late-onset of VMS increases the risk of CVD and all-cause mortality (Szmuilowicz et al. 2011). A recent systematic review conducted by Armeni et al. (2023) showed VMS increases the risk of CVD for those women aged less than 60 years suggesting that age might be a mediating factor in the association between these two processes. A pooled analysis of six prospective studies reported both early and late-onset of VMS are associated with an increased risk of CVD (Zhu et al. 2020). The two contrasting findings probably result from the use of two different definitions used in defining the onset of VMS. In the WHI-OS study, early-onset of VMS was defined as VMS at the onset of menopause, while late-onset was defined as VMS at the time of enrollment in the study, which was around 63.3 years at the time of interview. On the other hand, in the pooled analysis, VMS, which first occurred before menopause was classified as early-onset, while the VMS that first occurred after menopause was classified as late-onset. Therefore, the difference in definition could account for the differential outcomes. It has been hypothesized that the mechanisms at play in the occurrence of early and late VMS are different. For instance, Szmuilowicz et al. (2011) argued that the chance of early-onset of VMS before the menopausal transition is a physiological response to typical hormonal fluctuations, while late-onset VMS could be a manifestation of vascular instability. Therefore, both early and late-onset of VMS exhibit different associations with CVD. However, further research is needed for a better understanding of this association.

A possible mechanism linking women with VMS and an increased risk of CVD is a potential up-regulation in the sympathetic nervous activity (Gastet et al. 2008). Some scholars are of the opinion that the narrowing of thermoneutral zone results in hot flushes, which appears to be closely related to elevated central nervous system levels of nor-epinephrine (Freedman 1999). Epinephrine and nor-epinephrine secreted from the sympathetic nervous system are the possible mediators for various vascular and metabolic abnormalities, including hypertension and increased total cholesterol levels (Engler and Engler 1995). The significant increase in body fat percentage in older women with VMS, as observed in previous studies may also be due to the secretion of nor-epinephrine from the sympathetic nerves (Gast et al. 2008). The association of VMS with increased catecholaminergic activity and modifications in calcitonin-related peptides, may increase the risk of CVD (Gupta et al. 2008). A study by Cagnacci et al. (2011) showed hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and increased cortisol concentration among those who experience VMS; this may represent another mechanism linking VMS with CVD risk factors such as insulin resistance and abnormal lipid metabolism. Since VMS is associated with thermoregulatory dysfunction, it alters the activity of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The altered activity of both ANS and HPA may serve as a common link between VMS and cardiovascular risk factors (Zhu et al. 2020). However, whether vasomotor symptoms precede the CVD risk factors or are symptomatic manifestations underlies adverse changes in a woman’s vasculature warrants further investigation. For example, studies show that increased BMI and blood pressure levels are associated with an increased secretion of NE from sympathetic nerves, which in turn leads to the incidence of VMS (Cagnacci et al. 2015; Thurston 2018). However, other studies show conflicting results (Mendelsohn et al. 1999; Randolph et al. 2005). Thus, there is a need for further research to establish the exact link between these two events.

Women during midlife may also experience psychological symptoms, such as depression, mood disturbance, loss of energy, loss of interest, forgetfulness, anxiety, panic attacks, irritability and lack of concentration that may impede coping and decrease the quality of life (Ohayon et al. 2006; Thurston et al. 2017; Gavaet al. 2019). Freeman (2015) reported that midlife women in their late-perimenopausal phase are three times more likely to develop depressive symptoms compared to premenopausal women. A decline in the estrogen levels during menopausal transition may trigger psychological symptoms by inhibiting the production of major neuroprotective factors and altering neurotransmission. This decline may interfere with the synthesis of catecholamines and increase the level of serotonin potentially leading to the development of psychological symptoms (Santoro et al. 2015; Gava et al. 2019).

Psychological disorders, including depression, anxiety, and panic attacks, are already known to be CVD risk factors in both men and women of any age (Walters et al. 2008; Player et al. 2011; Brunner et al. 2014). Studies revealed that bothersome psychological symptoms are associated with increased CVD risk factors among midlife women (Ward et al. 1994; Smoller et al. 2003; Collins et al. 2007; Low et al. 2010; Im et al. 2016). Lack of sleep, depression and panic disorder that are indicative of poor physical and mental health, have been associated with an increased risk of CVD (Cappuccio et al. 2011; Laughsand et al. 2014). For example, a multi-ethnic study reported that postmenopausal women with severe psychological symptoms experience an increased risk of CVD related mortality (Im et al. 2016). Research indicates that both psychological symptoms and CVD risk factors could be influenced by the hormonal changes that occur during the menopausal transition. These hormonal alterations may bring changes in the hypothalamic-adrenal axis, serotonergic transmission, and the renin-angiotension-aldosterone system, which in turn increases the risk of CVD (Im et al. 2016; Muka et al. 2016). Scholars are of the opinion that depression and anxiety result in autoimmune activation, leading to increased blood pressure levels, decreased endothelial dysfunction, and increased platelet activity; all of which contribute to the development of CVD (Carney et al. 2005; Mittleman and Mostofsky 2011). The sympathetic nervous activation following the psychological symptoms could also mediate the increased risk of CVD (Esler et al. 2004). Another plausible mechanism explains that the co-occurrence of psychological symptoms and CVD risk factors is because of altered systematic inflammatory response; and this is influenced by the hormonal changes during menopause (Im et al. 2016).

It is postulated that menopausal symptoms affect cardiovascular health through established risk factors such as elevated BMI and central obesity (De Wit et al. 2009; Lallukka et al. 2012). Previous studies show a significant association between obesity and mood dysregulation (Glaus et al. 2019). Adipokines produced by adipose tissues activate systemic inflammation. This affects the brain and leads to various psychological symptoms (Ali et al. 2020). On the other hand, there are assumptions that psychological symptoms related to menopause increase the number of cytokines and free radicals, resulting in more fat deposition (Elavsky and Gold 2009); thus, the association can perhaps be explained to be bi-directional. Obesity may also induce low self-esteem among midlife women, resulting in mood dysregulation to some extent (Yaylali et al. 2010). The Epic-Norfolk study reported central obesity to be significantly associated with psychological symptoms, rather than general obesity (Myint et al. 2006). However, conflicting findings have also been reported (Ward Ritacco et al. 2015; Glaus et al. 2019).

Sleep disturbance is also associated with increased CVD risk factors like hypertension (Capuccio et al. 2011), obesity (Li 2021), type 2 diabetes mellitus (Cappucio et al. 2010), and atherogenic lipid profile (Kaneita et al. 2008; Tsiptsios et al. 2022). The exact mechanism underlying these associations is not fully understood. The possible mechanisms linking short durations of sleep to adverse health outcomes include reciprocal changes in circulating levels of leptin and ghrelin (Taheri et al. 2004); these changes would increase appetite, caloric intake, reduce energy expenditure and facilitate the development of obesity, and impair glycaemic control, which ultimately increases the risk of CVD (Khakpash et al. 2023).

The association between psychological symptoms and CVD risk factors could be mediated by other factors, such as ethnicity. For example, a multi-ethnic study found association between psychological symptoms and CVD risk factors varies across different ethnic groups, with Asian women showing the strongest association compared to the other ethnic groups (Im et al. 2016). The studies interpreted the strongest association among Asian women in the context of Asian culture, which prohibits the expression of psychological symptoms due to the stigmatization of mental illness (Kramer et al. 2002; Im et al. 2016). On the contrary, there are studies that reveal no ethnic variances in the association between psychological symptoms and CVD in midlife women (Ferketich et al. 2000; Franco et al. 2015). Researchers are of the opinion that the association may not be greatly influenced by social-cultural factors, although women’s socio-economic position, reproductive history, cultural beliefs, attitudes, knowledge, and perception could affect psychological symptoms (Ali et al. 2020; Weidner et al. 2020) and CVD risk factors independently (Tedesco et al. 2015; Beussink-Nelson et al. 2022).

Depressive symptom is a greater risk factor for CVD compared to other psychological symptoms (Smoller et al. 2003; Wright et al. 2014). Pathophysiological alterations that occur due to depression may affect the cardiovascular system by increasing variability in heart rate and platelet aggregation (Nemeroff 2008). Wright et al. (2014) posited that hormonal fluctuations experienced during menopause affect the systematic inflammatory process, which, in turn, increases the frequency of psychological symptoms and CVD risk factors. Heart rate and blood pressure increase during psychological stress (tension or anxiety) due to the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and adrenal medullary release of epinephrine, which, in turn, alter insulin resistance and lipid metabolism (Steptoe et al. 2006); some inconsistent findings have also been reported (Ward et al. 1994). Literature reveals an association of emotional distress with CVD risk factors, such as central obesity (Elavsky and Gold 2009). Emotional distress increases the production of cytokines and free radicals, resulting in the increase in central deposition of body fat (Elavsky and Gold 2009). Some studies have demonstrated that obesity and metabolic syndrome, characterized by impaired glucose and lipid metabolism, are independently associated with depression (Schmitz et al. 2018; Moazzami et al. 2019). The underlying mechanism linking obesity and depression is a complex pathway. Cerebral insulin resistance develops in obese women due to the depletion of adiponectin, which is a hormone derived from the adipose tissue and regulates the metabolism of glucose and lipids (Nguyen 2020). Obesity might also trigger major oxidative and inflammatory pathways, leading to neuroinflammation, which is a crucial factor in the development of mood and cognitive disorders, such as anxiety and depression (Kiecolt-Glaser et al. 2015). These are the possible pathways linking psychological symptoms of menopause and CVD risk factors among women (Schmitz et al. 2018; Moazzami et al. 2019). Future studies should address whether psychological symptoms precede the CVD risk factors or whether the CVD risk factors induce depression and anxiety among midlife women.

Urogenital symptoms also show a significant association with CVD. For example, a recent study conducted by Cagnacciet al. (2022) among 504 postmenopausal women revealed genito-urinary symptoms are more likely to be associated with CVD risk factors rather than hot flushes. Some earlier studies have also investigated the association between sexual symptoms and metabolic problems (Lee et al. 2015; Russo et al. 2015; Lee 2019; Semczuk-Kaczmarek et al. 2021). For example, a systematic review conducted by Hunskaar (2008) showed that central obesity, higher BMI, higher low density lipoprotein cholesterol, and fasting blood glucose levels are significantly associated with genito-urinary problems like urinal incontinence. Kilinc et al. (2017), on the other hand, reported that the incidence of severe coronary artery disease to be higher in patients with urinal incontinence, Park et al. (2018) showed that abdominal obesity is more likely to be associated with urinal incontinence compared to general obesity. However, studies investigating the link between sexual symptoms and obesity are limited and show inconsistent results. It is postulated that central obesity is associated with increased pressure on the urinary bladder, and adipose tissue acts, such as a neuroendocrine organ that produces inflammatory factors and induces the sympathetic nervous system (Subaket et al. 2009; Tang et al. 2022); this, in turn, leads to the development of some urinary symptoms like urinal incontinence. It is postulated that metabolic co-morbidity, such as obesity and dyslipidemia, could increase the severity of urogenital symptoms, possibly by causing inflammation, oxidative stress, hormonal disruptions, and impaired blood vessel formation (Zhu et al. 2024). In addition, there is evidence showing that women with an altered lipid profile exhibit activation of inflammatory pathways, a decrease in neuroprotective factors, damage to DNA, and apoptosis ultimately leading to the development of urogenital symptoms (Zhu et al. 2024). The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey reported moderate to severe urogenital symptoms to be associated with an increased risk of diabetes mellitus (Lin et al. 2013; Hwang et al. 2015). The exact mechanism linking urogenital symptoms and CVD risk factors is less understood. Previous studies show that some common factors such as estrogen deficiency, endothelial dysfunction, increased Rho-kinase activation, impaired nitric-oxide synthase pathway in the endothelium, autonomic hyperactivity with sympathetic dysregulation are likely to be linked with urogenital symptoms and CVD (Fusco et al. 2013; Semczuk-Kaczmarek et al. 2021). Age-related changes in the bladder structure and function seem to play a central role in the occurrence of urogenital symptoms. For example, endothelial dysfunction in the pelvic vascular system is considered to play a role in urinal incontinence. The common pathway linking hypertension and urogenital symptoms could be explained by increased sympathetic activity and altered alpha 2-adrenoreceptor activity. Furthermore, diabetes mellitus can increase the severity of urogenital symptoms through neurogenic bladder dysfunction (Russo et al. 2015). However, these associations cannot be explained as a cause-effect relation. For example, it appears from a recent study that patients with coronary artery disease have a higher severity of urogenital symptoms; this may indicate a significant role of CVD in the pathophysiology of urogenital symptoms (Semczuk-Kaczmarek et al. 2021). The same study further reported association of increasing severity of urogenital symptoms with age, metabolic biomarkers and arterial hypertension. It is argued that a healthy lifestyle, antihypertensive therapy with angiotensin II receptor blockers, and lipid lowering medicines like statins could reduce both CVD and the severity of urogenital symptoms (Semczuk-Kaczmarek et al. 2020).

| Association | Researchers | Outcomes |

| VMS and CVD risk factors VMS and hypertension VMS and total cholesterol level VMS and body fat percentage VMS and insulin resistance |

Bechlioulis et al. 2010; Kagitani et al. 2014; Jackson et al. 2016 Gast et al. 2008; Thurston et al. 2012 Herber-Gast et al. 2013; Gallichio et al. 2014 Szmuilowicz et al. 2011; Cagnacci et al. 2011 |

Incidence of VMS increases the likelihood of hypertension compared to those without VMS. VMS is associated with a derangement of the lipid profile. Incidence of VMS increases the likelihood of derangement of the lipid profile. Greater the degree of severity of VMS, higher is the likelihood of body fat percentage. Early onset of VMS is not associated with CVD risk factors such as insulin resistance, but late-onset of VMS increases the risk of CVD and all-cause mortality. |

| Psychological symptoms and CVD Psychological symptoms, blood glucose and lipid profile Psychological symptoms and hypertension Psychological symptoms and obesity | Cappucio et al. 2010; Wright et al. 2014; Tsiptsios et al. 2022 Im et al. 2016; Muka et al. 2016 Taheri et al. 2004; Glaus et al. 2019; Khakpash et al. 2023 |

Psychological symptoms increase the activity of sympathetic nervous system and adrenal medullary release of epinephrine, leading to insulin resistance and abnormal lipid metabolism. Depression and anxiety result in autoimmune activation, leading to increased blood pressure levels, decreased endothelial dysfunction, and increased platelet activity. Psychological distress would increase appetite, caloric intake, reduce energy expenditure and facilitate the development of obesity. |

| Urogenital symptoms and CVD Urogenital symptoms and insulin resistance Urogenital symptoms and hypertension |

Lin et al. 2013; Hwang et al. 2015 Fusco et al. 2013; Semczuk-Kaczmarek et al. 2021 Park et al. 2018; Tang et al. 2022 |

Moderate to severe levels of urogenital symptoms is associated with increased risk of insulin resistance. Incidence of hypertension increases the likelihood of the severity of urogenital symptoms. Abdominal obesity is more likely to be associated with urinal incontinence compared to general obesity. |

Our review suggests that the decline in the estrogen levels remains the common origin for menopausal symptoms and CVD risk factors during mid-life affecting the quality of life of women. This narrative review revealed the following unmet gaps in research. (1) How different is the association between menopausal symptoms and CVD risk factors across different ethnic groups? (2) Are menopausal symptoms associated with the CVD risk factors and, if so, determine the degree of the CVD risk factors? (3) Does the age of onset of menopausal symptoms has an association with the CVD risk factors? (4) To what extent VMS, psychological, and urogenital symptoms independently or in combination play roles in predicting CVD risk factors? (5) Does women with hormone replacement therapy have reduced risk of menopausal symptoms and CVD risk factors? (6) The existing literature has rarely reported studies from low-middle-income countries where the menopausal age is advancing (Mozumdar et al. 2015). Are, thus, women from these parts of the world more likely to be at a risk of CVD?

Our review suggests that women who experience vasomotor, psychological, and urogenital symptoms are likely to have a higher risk of CVD compared to those who have not experienced such symptoms. Our review also indicates the potential usefulness of menopausal symptoms as marker for CVD risk factors during midlife.

Conflict of interests

The authors declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contribution

The first author (DK) has contributed 50% by designing and partially drafting the manuscript. The second author (SR) has contributed 50% by reviewing the manuscript.

Ali AM, Ahmed AH, Smail L. 2020. Psychological climacteric symptoms and attitudes toward menopause among Emirati women. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(14): 5028. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145028

Armeni A, Anagnostis P, Armeni E, Mili N, Goulis D, Lambrinoudaki I. 2023. Vasomotor symptoms and risk of cardiovascular disease in peri and postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 171: 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2023.02.004

Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, Bromberger JT, Everson-Rose SA, Gold EB, et al. 2015. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med 175(4): 531–539. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8063

Bechlioulis A, Kalantaridou SN, Naka KK, Chatzikyriakidou A, Calis KA, Makrigiannakis A, et al. 2010. Endothelial function, but not carotid intima-media thickness, is affected early in menopause and is associated with severity of hot flushes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95(3): 2009–2062. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2009-2262

Beussink-Nelson L, Baldridge AS, Hibler E, Bello NA, Epps K, Cameron KA, et al. 2022. Knowledge and perception of cardiovascular disease risk in women of reproductive age. Am J Prev Cardiol 11: 100364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpc.2022.100364

Brunner EJ, Shipley MJ, Britton AR, Stansfeld SA, Heuschmann PU, Rudd AG, et al. 2014. Depressive disorder, coronary heart disease, and Stroke: dose-response and reverse causation effects in the Whitehall II cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 21(3): 340–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487314520785

Cagnacci A, Cannoletta M, Caretto S, Zanin R, Xholli A, Volpe A. 2011. Increased cortisol level: a possible link between climacteric symptoms and cardiovascular factors. Menopause 18 (3): 273–278. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3181f31947

Cagnacci A, Cannoletta M, Palma F, Zanin R, Xholli A, Volpe A. 2012. Menopausal symptoms and risk factors for cardiovascular disease in postmenopause. Climacteric 15(2): 157–162. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2011.617852

Cagnacci A, Palma F, Romani C, Xholli A, Bellafronte M, Di Carlo C. 2015. Are climacteric complaints associated with risk factors of cardiovascular disease in peri-menopausal women? Gynecol Endocrinol 31(5): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.3109/09513590.2014.998188

Cagnacci A, Gambera A, Bonaccorsi G, Xholli A. 2022. Relation between blood pressure and genitor-urinary symptoms in the years across the menopausal age. Climacteric 25(4): 395–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2021.2006176

Cakmak HA, Cakmak BD, Yumru AE, Aslan S, Enhos A, Kalkan AK, et al. 2015. The relation between blood pressure, blood glucose and bone mineral density in postmenopausal Turkish women. Ther Clin Risk Manag 11:1641–1648. https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S95017

Carney RM, Freedland KE, Veith RC. 2005. Depression, the autonomic nervous system, and coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med 67 (Suppl 1): S29–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000162254.61556.d5

Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. 2010. Quantity and quality of sleep and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 33(2):414–420. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-1124

Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. 2011. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J 32(12):148–192. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehr007

Carr MC. 2003. The emergence of metabolic syndrome with menopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88(6): 2404–2411. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2003-030242

Cohen L, Soares C, Vitonis AF, Otto MW, Harlow BL. 2006. Risk for new onset of depression during the menopausal transition: the Harvard study of moods and cycles. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63(4): 385–390. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.385

Collins P, Rosano G, Casey C, Daly C, Gambacciani M, Hadji P, et al. 2007. Management of cardiovascular risk in the peri-menopausal woman: a consensus statement of European cardiologists and gynaecologists. Eur Heart J 28(16):2028–2040. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehm296

Da Fonseca AM, Bagnoli VR, Souza MA, Azevedo RS, Couto EDB Jr, Soares JM Jr, et al. 2013. Impact of Age and Body Mass on the Intensity of Menopausal Symptoms in 5968 Brazilian Women. Gynecol Endocrinol 29(2):116–118. https://doi.org/10.3109/09513590.2012.730570

Dam V, Dobson AJ, Onland-Moret NC, van der Schouw YT, Mishra GD. 2020. Vasomotor menopausal symptoms and cardiovascular disease risk in midlife: A longitudinal study. Maturitas 133: 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.12.011

De Wit LM, Van Straten A, Van Herten N, Penninx BW, Cuijpers P. 2009. Depression and body mass index, a u shaped association. BMC Public Health 9:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-14

Dennerstein L, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Guthrie JR, Burger HG. 2000. A prospective population-based study of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 96(3): 351–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00930-3

Duffy OK, Iversen L, Hannaford PC. 2013. Factors Associated With Reporting Classic Menopausal Symptoms Differ. Climacteric 16(2):240–251. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2012.697227

El Khoudary SR, Aggarwal B, Beckie TM, Hodis HN, Johnson AE, Langer RD, et al. 2020. Menopause transition and cardiovascular disease risk: Implications for timing of early prevention: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 142 (25):e506–e532. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000912

Elavsky S, Gold CH. 2009. Depressed mood but not fatigue mediate the relationship between physical activity and perceived stress in middle-aged women. Maturitas 64(4): 235–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.09.007

Engler MB, Engler MM. 1995. Assessment of the cardiovascular effects of stress. J Cardiovasc Nurs 10(1): 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005082-199510000-00005

Esler M, Alvarenga M, Lambert G, Kaye D, Hastings J, Jennings G, et al. 2004. Cardiac sympathetic nerve biology and brain monoamine turnover in panic disorder. Ann N Y Acad Sc 1018:505–514. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1296.062

Ferketich AK, Schwartzbaum JA, Frid DJ, Moeschberger ML. 2000. Depression as an Antecedent to Heart Disease Among Women and Men in the NHANES I Study. Arch Intern Med 160(9):1261–1268. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.160.9.1261

Franco OH, Muka T, Colpani V, Kunutsor S, Chowdhury S, Chowdhury R, et al. 2015. Vasomotor symptoms in women and cardiovascular risk markers: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 81(2015): 353–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.04.016

Freedman RR, Krell W. 1999. Reduced thermoregulatory null zone in postmenopausal women with hot flashes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 181(1): 66–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70437-0

Freedman RR. 2005. Pathophysiology and treatment of menopausal hot flashes. Semin Reprod Med 23(2): 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-869479

Freeman EW. 2015. Depression in the menopause transition: risks in the changing hormone milieu as observed in the general population. Womens Midlife Health 1:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-015-0002-y

Fusco F, D’Anzeo G, Sessa A, Pace G, Rossi A, Capece M, et al. 2013. BPH/LUTS and ED: common pharmacological pathways for a common treatment. J Sex Med 10(10):2382–2393. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12261

Gallicchio L, Miller SR, Kiefer J, Greene T, Zacur HA, Flaws JA. 2010. Risk factors for hot flashes among women undergoing the menopausal transition: baseline results from the midlife women’s health study. Menopause 22(10): 1098–1107. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000434

Gallichio L, Miller SR, Kiefer J, Greene T, Zacur HA, Flaws JA. 2014. Change in body mass index, weight, and hot flashes: a longitudinal analysis from the midlife women’s health study. J Womens Health. 23(3): 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2013.4526

Gast GC, Grobbee DE, Pop VJM, Keyzer JJ, Wijnands-van Gent CJM, Samsioe GN, et al. 2008. Menopausal complaints are associated with cardiovascular risk factors. Hypertension 51(6): 1492–1498. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.106526

Gast GCM, Pop VJM, Samsioe GN, Grobbee DE, Nilsson PM, Keyzer JJ, et al. 2011. Vasomotor menopausal symptoms are associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease. Menopause 18(2): 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3181f464fb

Gava G, Orsili I, Alvisi S, Mancini I, Seracchioli R, Meriggiola MC. 2019. Cognition, Mood and Sleep in Menopausal Transition: The Role of Menopause Hormone Therapy. Medicina (Kaunas) 55(10):668. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55100668

Glaus J, Cui L, Hommer R, Merikangas KR. 2019. Association between mood disorders and BMI/overweight using a family study approach. J Affect Disord 248:131–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.011

Gray KE, Katon JG, LaBlanc ES, Woods NF, Bastian LA, Reiber GE, et al. 2018. Vasomotor symptom characteristics: are they risk factors for incident diabetes? Menopause 25(5): 520–530. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001033

Gupta P, Harte A, Sturdee DW, Sharma A, Barnett AH, Kumar S, et al. 2008. Effects of menopausal status on circulating calcitonin age-related peptide and adipokines: implications for insulin resistance and cardiovascular risks. Climacteric 11(5): 364–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697130802378493

Herber-Gast GCM, Mishra GD, van der Schouw YT, Brown WJ, Dobson AJ. 2013. Risk factors for night sweats and hot flushes in midlife: results from a prospective cohort study. Menopause 20(9): 953–959. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0b013e3182844a7c

Hitchcock CL, Elliott TG, Norman EG, Stajic V, Teede H, Prior JC. 2012. Hot flushes and night sweats differ in associations with cardiovascular markers in healthy early postmenopausal women. Menopause 19(11):1208–1214. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e31825541cc

Huang WY, Chang CC, Chen DR, Kor CT, Chen TY, Wu HM. 2017. Circulating leptin and adiponectin are associated with insulin resistance in healthy postmenopausal women with hot flashes. Plos One 12 (4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176430

Hunskaar S. 2008. A systematic review of overweight and obesity as risk factors and targets for clinical intervention for urinary incontinence in women. Neurourol Urodyn 27 (8): 749–757. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20635

Hwang EC, Kim SO, Nam DH, Yu HS, Hwang I, Jung SI, et al. 2015. Men with Hypertension are More Likely to Have Severe Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Large Prostate Volume. Low Urin Tract Symptoms 7(1):32–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/luts.12046

Im EO, Kim J, Chee E, Chee W. 2016. The Relationships between Psychological Symptoms and Cardiovascular Symptoms Experienced during Menopausal Transition: Racial/Ethnic Differences. Menopause 23(4): 396–402. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000545

Jackson EA, El Khoudary SR, Crawford SL, Matthews K, Joffe H, Chae C, et al. 2016. Hot flash frequency and blood pressure: Data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. J WomensHealth(Larchmt) 25(12): 1204–1209. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2015.5670

Kagitani H, Asou Y, Ishihara N, Hoshide S, Kario K. 2014. Hot flashes and blood pressure in middle-aged Japanese women. Am J Hypertens 27(4): 503–507. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpt125

Kaneita Y, Uchiyama M, Yoshiike N, Ohida T. 2008. Associations of usual sleep duration with serum lipid and lipoprotein levels. Sleep 31(5):645–652. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/31.5.645

Kershaw EE, Flier JS. 2004. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89(6): 2548–2556. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-0395

Khakpash M, Khosravi A, Emamian MH, Hashemi H, Fotouhi A, Khajeh M. Association between sleep quality and duration with serum lipid profiles in older adults: A population-based study. Endocrine and Metabolic Science 13:100148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.endmts.2023.100148

Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Habash DL, Fagundes CP, Andridge R, Peng J, Malarkey WB, et al. 2015. Daily stressors, past depression, and metabolic responses to high-fat meals: a novel path to obesity. Biol Psychiatry 77(7): 653–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.05.018

Kilinc MF, Yasar E, Aydin HI, Yildiz Y, Doluoglu OG. 2018. Association between coronary artery disease severity and overactive bladder in geriatric patients. World J Urol 36 (1):35–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-017-2098-1

Lallukka T, Haario P, Lahelma E, Rahkonen O. 2012. Associations of relative weight with subsequent changes over time in insomnia symptoms: a follow up study among middle aged women and men. Sleep Med 13 (10): 1271–1279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2012.06.020

Laugsand LE, Strand LB, Platou C, Vatten LJ, Janszky I. 2014. Insomnia and the risk of incident heart failure: a population study. Eur Heart J 35(21):1382–1393. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht019

Lee SH, Lee SK, Choo MS, Ko KT, Shin TY, Lee WK, et al. 2015. Relationship between Metabolic Syndrome and Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: Hallym Aging Study. Biomed Res Int 2015:130917. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/130917

Lee HY, Moon JE, Sun HY, Doo SW, Yang WJ, Song YS, et al. 2019. Association between lower urinary tract symptoms and cardiovascular risk scores in ostensibly healthy women. BJU Int 123(4):669–675. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.14577

Li, Q. 2021. The association between sleep duration and excess body weight of the American adult population: a cross-sectional study of the national health and nutrition examination survey 2015–2016. BMC Public Health 21(1):335. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10369-9

Lin HJ, Weng SF, Yang CM, Wu MP. 2013. Risk of hospitalization for acute cardiovascular events among subjects with lower urinary tract symptoms: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS One 8(6):e66661. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066661

Low CA, Thurston RC, Matthews KA. 2010. Psychosocial factors in the development of heart disease in women: current research and future directions. Psychosom Med 72(9): 842–854. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181f6934f

Matthews KA, Chen X, Barinas-Mitchell E, Brooks MM, Derby CA, Harlow S, et al. 2021. Age at menopause in relationship to lipid change sand subclinical carotid disease across 20 years: Study of women’s health across the nation. J Am Heart Assoc 10(18): e021362. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.121.021362

Mendelson ME, Kara RE. 1999. Mechanisms of Disease. NEJM 340:1801–1810.

Mittleman MA, Mostofsky E. 2011. Physical, psychological and chemical triggers of acute cardiovascular events: preventive strategies. Circulation 124(3):346–354. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.968776

Moazzami K, Lima BB, Sullivan S, Shah A, Bremner JD, Vaccarino V. 2019. Independent and joint association of obesity and metabolic syndrome with depression and inflammation. Health Psychol 38(7): 586–595. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000764

Muka T, Oliver-Williams C, Colpani V, Kunutsor S, Chowdhury S, Chowdhury R, et al. 2016. Association of vasomotor and other menopausal symptoms with risk of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One 11(6):e0157417. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157417

Myint PK, Welch AA, Luben RN, Wainwright NWJ, Surtees PG, Bingham SA, et al. 2006. Obesity Indices and Self-Reported Functional Health in Men and Women in the EPIC-Norfolk. Obesity (Silver Spring) 14(5):884–893. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2006.102

Nemeroff CB. 2008. The curiously strong relationship between cardiovascular disease and depression in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 16(11):857–860. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e318189806a

Nguyen TMD. 2020. Adiponectin: Role in Physiology and Pathophysiology. Intern J Prev Med 11:136. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_193_20

Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MV. 2004. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep 27(7):1255–1273. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/27.7.1255

Player MS, Peterson LE. 2011. Anxiety disorders, hypertension and cardiovascular risk: a review. Int J Psychiatry Med 41(4): 365–377. https://doi.org/10.2190/PM.41.4.f

Randolph JF, Sowers MF, Bondarenko I, Gold EB, Greendale GA, Bromberger JT, et al. 2005. The relationship of longitudinal change in reproductive hormones and vasomotor symptoms during the menopausal transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90(11):6106–6112. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2005-1374

Russo GI, Castelli T, Privitera S, Fragalà E, Favilla V, Reale G, et al. 2015. Increase of Framingham cardiovascular disease risk score is associated with severity of lower urinary tract symptoms. BJU Int 116(5):791–796. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.13053

Santoro N, Epperson CN, Mathews SB. 2015. Menopausal symptoms and their management. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 44(3): 497–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2015.05.001

Schlaich M, Straznicky N, Lambert E, Lambert G. 2015. Metabolic Syndrome: A Sympathetic Disease? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 3(2):148–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70033-6

Schmitz N, Deschênes SS, Burns RJ, Danna SM, Franco OH, Ikram MA, et al. 2018. Cardiometabolic dysregulation and cognitive decline: potential role of depressive symptoms. Br J Psychiatry 212(2): 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2017.26

Semczuk-Kaczmarek K, Rys-Czaporowska A, Platek AE, Szymanski FM.2021. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with cardiovascular disease. Cent European J Urol 74(2):190–195. https://doi.org/10.5173/ceju.2021.0370.R1

Sherman S, Miller H, Nerukar L. 2005. NIH state-of-the-science conference on management related symptoms. American Journal of Medicine 22(1): 1–38.

Smoller JW, Pollack MH, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Barton B, Hendrix SL, Jackson RD, et al. 2003. Prevalence and correlates of panic attacks in postmenopausal women: results from an ancillary study to the Women’s Health Initiative. Arch Intern Med 163(17):2041–2050. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.17.2041

Son MK, Lim NK, Lim J, Cho J, Chang Y, Park H. 2015. Difference in blood pressure between early and late menopausal transition was significant in healthy Korean women. BMC Womens Health 15:64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-015-0219-9

Steptoe A, Donald AE, O’Donnell K, Marmot M, Deanfield JE. 2006. Delayed blood pressure recovery after psychological stress is associated with carotid intima-media thickness: Whitehall psychology study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26 (11): 2547–2551. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.ATV.0000242792.93486.0d

Subak LL, RichterHE, Hunskaar S. 2009. Obesity and urinary incontinence: epidemiology and clinical research update. J Urol 182(6Suppl): S2–S7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.071

Svartberg J, von Muhlen D, Kritz-Silverstein D, Barrett-Connor E. 2009. Vasomotor symptoms and mortality: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Menopause 16(5):888–891. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a4866b

Szmuilowicz ED, Mansion JE, Rossouw JE, Howard BV, Margolis KL, Greep NC, et al. 2011.Vasomotor symptoms and cardiovascular events among postmenopausal women. Menopause 18(6): 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3182014849

Taheri S, Lin L, Austin D, Young T, Mignot E. 2004. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med 1(3):e62. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0010062

Tang R, Fan Y, Luo M, Zhang D, Xie Z, Huang F, et al. 2022. General and central obesity are associated with increased severity of VMS and sexual symptoms of menopause among Chinese women: A longitudinal study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 13:814872. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.814872

Tedesco LMR, Di Giuseppe G, Napolitano F, Angelillo IF. 2015. Cardiovascular dis–eases and women: knowledge, attitudes, and behavior in the general population in Italy. Biomed Res Int 2015: 324692. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/324692

Thurston RC, Bromberger JT, Joffe H, Avis NE, Hess R, Crandall CJ, et al. 2008. Beyond frequency: who is most bothered by vasomotor symptoms? Menopause 15(5): 841–847. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e318168f09b

Thurston RC, El Khoudary SR, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Crandall CJ, Gold E, SternfeldB et al. 2012. Vasomotor symptoms and lipid profile in women transitioning through menopause. ObstetGynecol 119(4): 753–761. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824a09ec

Thurston RC, Chang Y, Mancuso P, Matthews KA. 2013. Adipokines, adiposity, and vasomotor symptoms during the menopause transition: findings from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. FertilSteril 100(3): 793–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.05.005

Thurston RC, Matthews KA, Chang Y, Santoro N, Barinas-Mitchell E, von Kȁnel R et al. 2016. Changes in heart rate variability during vasomotor symptoms among midlife women. Menopause 23(5): 499–505. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000586

Thurston RC, Johnson BD, Shufelt CL, Braunstein GD, Berga SL, Stanczyc FZ, et al. 2017. Menopausal symptoms and cardiovascular disease mortality in Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). Menopause 24 (2):126–132. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000731

Thurston RC. 2018. Vasomotor symptom: natural history, physiology, and links with cardiovascular health. Climacteric 21(2): 96–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2018.1430131

Townsend N, Wilson L, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Rayner M. 2016. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: epidemiological update 2016. Eur Heart J 37(42): 3232–3245. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw334

Tsiptsios D, Leontidou E, Fountoulakis PN, Ouranidis A, Matziridis A, Manolis A, et al. 2022. Association between sleep insufficiency and dyslipidemia: a cross-sectional study among Greek adults in the primary care setting. Sleep Sci 15(Spec 1):49–58. https://doi.org/10.5935/1984-0063.20200124

Tuomikoski P, Pelton HS. 2017. Vasomotor symptoms and metabolic syndrome. Maturitas 97: 61–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.12.010

Walters K, Rait G, Petersen I, Williams R, Nazareth I. 2008. Panic disorder and risk of new onset coronary heart disease, acute myocardial infarction, and cardiac mortality: cohort study using the general practice database. Eur Heart J 29(24): 2981–2988. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehn477

Ward KD, Sparrow D, Landsberg L, Young JB, Vokonas PS, Weiss ST. 1994. The relationship of epinephrine excretion to serum lipid levels: the Normative Aging Study. Metabolism 43(4): 509–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/0026-0495(94)90085-x

Ward-Ritacco CL, Adrian AL, O’Connor PJ, Binkowski JA, Rogers LQ, Johnson MA, et al. 2015. Feelings of Energy are Associated with Physical Activity and Sleep Quality, But Not Adiposity, in Middle-Aged Postmenopausal Women. Menopause 22(3):304–311. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000315

Weidner K, Bittner A, Beutel M, Goeckenjan M, Brähler E, Garthus-Niegel S. 2020. The role of stress and self-efficacy in somatic and psychological symptoms during the climacteric period – Is there a specific association? Maturitas 136:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.03.004

Woods R, Hess R, Biddington C, Federico M. 2020. Association of lean body mass to menopausal symptoms: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Womens Midlife Health 6:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-020-00058-9

Wright L, Simpson W, Van Lieshout RJ, Steiner M. 2014. Depression and cardiovascular disease in women: is there a common immunological basis? A theoretical synthesis. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis 8(2):56–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753944714521671

Yaylali GF, Tekekoglu S, Akin F. 2010. Sexual Dysfunction in Obese and Overweight Women. Int J Impot Res 22(4):220–226. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijir.2010.7

Zhu D, Chung HF, Dobson AJ,Pandeya N, Anderson DJ, Kuh D et al. 2020.Vasomotor menopausal symptoms and risk of cardiovascular disease: A pooled analysis of six prospective studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 223 (6): 898 e1–898 e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.039

Zhu F, Chen M, Xiao Y, Huang X, Chen L, Hong L. 2024. Synergistic interaction between hyperlipidemia and obesity as a risk factor for stress urinary incontinence in Americans. Sci Rep 14: 7312. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56744-5