Available online at: https://doi.org/10.18778/1898-6773.85.4.01

School of Medical Sciences, Anatomy, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Department of Archaeology, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia

History, Brigham Young University-Idaho, USA

Biological Anthropology and Comparative Anatomy Research Unit, School of Biomedicine, University of Adelaide, Australia

Institute of Evolutionary Medicine, University of Zurich, Winterthurerstr. 190, 8057 Zurich, Switzerland

ABSTRACT: Application of forensic identification methods to establish authenticity of a historical photograph is made. Joseph Smith Junior was the Prophet and founder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, often referred to as Mormons. In 1844 Joseph and his brother Hyrum were shot and killed by a mob of angry men who opposed his church and its followers. Shortly after death, Joseph’s face was moulded, and a death mask was made. Photography was invented during the life of Joseph Smith Jnr and there are reports that he had a daguerreotype (photograph) taken, but no image has been verified to be of him.

A photographic image of an Illinois man from the 1840s is linked by circumstantial evidence, such as similar clothing, to Joseph Smith Jnr and the photographer’s studio being close to where Joseph Smith III was at the time the photograph has been produced. A morphological comparison is made between the death mask and the photograph in order to establish the likelihood that the man in the photograph is the prophet. Sixteen points of anatomical similarity were found between the death mask and the photograph, the most compelling of which is asymmetry of the face and a possible scar in the area of the left eyebrow. Superimposition confirmed morphological similarity. Finding of close morphological similarity is not an ultimate proof of identification, but increases the probability that the photograph depicts Joseph Smith Junior. This is the first case of an anatomical comparison between a death mask and a photograph.

KEY WORDS: Joseph Smith, image analysis, morphology, death mask, anatomy

The testimony of Joseph Smith Junior recounts that on the evening of September 21st 1823, he was visited by a messenger of God who instructed him to find and translate golden plates to what is known as ‘The book of Mormon’ (The testimony of the prophet Joseph Smith, The Book of Mormon). In March 1830, ‘The Book of Mormon, Another Testament of Jesus Christ’ was published, and Joseph Smith Jr became known as a prophet. In April of the same year, the prophet Joseph Smith organised The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) and became its first president (Quinn 1976).

In 1839 the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints settled in Nauvoo, Illinois. Joseph Smith Jnr was elected the mayor of Nauvoo in 1842; in February 1844, he was nominated to run for President of the United States. Joseph Smith’s presidential bid chose not to be affiliated with either major party and was seen as a political and religious threat. In June 1844, the Nauvoo Expositor accused Joseph Smith Jnr of immorality. This led to a political row involving the State Governor and surrounding towns that resulted in Joseph being fined $500, jailed and charged with causing riot and with treason (Taylor 2017).

On June 27th 1844, Joseph Smith Jnr was shot and killed after a mob ambushed the jail where he and his brother Hyrum were being held. After Joseph was shot, he fell through a second story window (Gayler 1957). This event has since been known as the ‘Martyrdom of Joseph Smith’ (McCarl 1962; Weber 2009).

On June 29th 1844 moulds were made of the brothers faces (Weber 2009) and masks were made from the moulds. It is reported that sometime after 1849 the masks came into possession of Philo Dibble (Weber 2009). This is the oldest known set of the death masks and they are currently located in the Museum of Church History and Art in Salt Lake City, commonly referred to as the ‘Dibble Death Masks’ (Weber 2009). These death masks are the most reliable representation of the face of Joseph Smith Jnr and his brother Hyrum to date.

There exists a lot of wonder surrounding the appearance of Joseph Smith Jnr as no photograph has been proven to be of the prophet and there is debate amongst scholars as to which historical records depicting his image are reliable. McCarl (1962) compiled a historical record of journal entries which reference the appearance of Joseph Smith Jnr by people who have claimed to have met him. These descriptions, while numerous, are somewhat contradictory and embellished to not describe his anatomical appearance but somehow derive his character from his features. Some describe him as having brown hair, while others claim it was a very light colour. His eyes received the greatest attention, some reported a blue colour, others hazel but the most intriguing descriptions were not anatomical but embellishments of personality, one person wrote of his eyes ‘…seemed to dive down to the innermost thoughts with their sharp penetrating gaze, a striking countenance, and with manners at once majestic yet gentile, dignified yet exceedingly pleasant’ (McCarl 1962). Some descriptions are consistent between those who met him and describe in detail anatomical features such as: thin lips, prominent nose, oblong/oval face, large forehead without a furrow, retreating forehead, eyes set back in the head (McCarl 1962). It would seem that people’s perception of him as a prophet and religious man, somewhat biased their opinions and descriptions of him to embellish his status as a prophet. Thus, these descriptions are not considered entirely reliable.

During his life, Joseph Smith Jnr reported posing for a reproduction of his likeness on two occasions. On June 25th 1842, Joseph wrote that he ‘sat for a drawing of my profile to be placed on a lithograph of the map of the city of Nauvoo’ (Smith 1842a). This image was the work of Sutcliffe Maudsley, known as the ‘Maudsley print’. Joseph Smith Jnr also reports having his likeness painted by ‘Brother Rogers’ in September of 1842, referring to David Rogers (Smith 1842b). There are two paintings which have been assigned as being painted by David Rogers, a profile picture and an anterior facing picture. Unfortunately, paintings are an artist’s interpretation of the person and are often touched up to eliminate any potential flaws. Therefore, the only proven, reliable representation of Joseph Smith is the death mask.

In 1910, Joseph Smith III wrote to the Salt Lake Tribune stating that the family was in possession of a daguerreotype of his father Joseph Smith Jnr (McCarl 1962). The daguerreotype he speaks of, was reportedly taken by Lucian Foster who had just returned from a mission in New York, for the Church of Jesus Christ (J. Smith, 2015). On April 29th 1844, Joseph Smith Jnr wrote in his journal ‘At home received a visit from Lucian R Foster of New York who gave me a gold pencil case…’ (Smith 1844). Joseph Smith Jnr. died two months later. The daguerreotype was the most prominent form of photography between 1839 and 1860 (Švadlena 2014). Many people have come forth with daguerreotypes claiming to be the prophet, however, none have been conclusively proven to be Joseph Smith Jnr (McCarl 1962). The latest of these claims has been made in 2022 when Ronald Roming and Lachlan Mackay presented a picture found in the locket inherited from Joseph Smith III’s son’s wife. The origins of this image are still discussed, while the similarity of the person depicted on this image to Joseph Smith Jnr is not apparent (Roming and Mckay 2022).

DH who had an old photographic image of a man taken in Illinois in her possession and wanted a facial comparison between this image and images of the Dibble death mask of Joseph Smith Jnr contacted TL who undertook the analysis reported here.

According to Houlton and Steyn (2018) there are four methods of facial comparison: holistic, photographic video superimposition, photoanthropometry and morphological. The holistic method involves a fast visual comparison between a living person and a photograph, usually performed by police and customs officers to confirm or deny an individual’s identity. Facial superimposition involves the overlay of two photos and assessment how well they fit over each other, often with animated image transitions which show various aspects of one photograph compared with the other (Houlton and Steyn 2018). Unfortunately, biases can be produced depending on the method used and quality of images. Photoanthropometry is the measurement of the face using dimensions and angles based on standardised anthropometric landmarks. Photoanthropometry and landmark precision has proved useful in identification, however, it requires calibration of images with surveying of the site for scale, and often expensive technology (Scoleri et al. 2014). In the absence of technology and site surveys (often not possible if it is not known where the image was taken or if there are no objects in the image) ratios will allow proportional measurements to be taken. Lucas et al. (2016) concluded that ratios are not precise enough to differentiate between adult individuals and thus cannot be used in facial or body comparisons of forensic significance. It has also been suggested that proportional measurements are subject to image distortion (Moreton and Morley 2011). Given the potential for bias in facial superimposition, and the unreliability of photoanthropometry and the inappropriate use of the holistic approach for image to image comparisons where time to complete the task is irrelevant, morphological analysis is the preferred method for facial identification. Facial identification methods are usually applied in cases of forensic significance (Lucas and Henneberg 2015b; Houlton and Steyn 2018), although, they can be applied to any case where identification is questioned.

The aim of the current paper is to establish the degree of anatomical similarity between the death mask of Joseph Smith Jnr and the image of a man from Illinois. This facial comparison is the first case of a systematic forensic comparison between an image and a death mask.

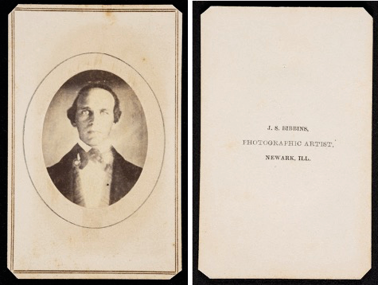

Figure 1 is a Carte de visite (CDV) image of an unknown man pictured in the anterior view. The Carte-de-visite was the most popular form of copying photographs from the 1860s to the 1880s (Burstow 2016). On the back of the photograph is text which reads ‘J.S Bibbins, Photographic Artist, Newark ILL’. This Carte-de-visite was examined by Gaiwan Weaver Art Conservation who produced a report stating that the image was an albumen print on CDV mount typical of the 1860s. The report says the image is a copy of an earlier photographic portrait, likely to be a daguerreotype or ambrotype.

Fig. 1. Carte-de-visite photograph of an unknown man pictured from the anterior view (left), the back of the CDV, showing details of the photographer (right)

In 1866 Joseph Smith III moved to Plano, Illinois, 10 miles away from Newark until his departure in 1881 (Smith 1979). J.S Bibbins (Joseph Slocum Bibbins) is recorded in the 1860s census as having the profession of ‘Artist’ (Bibbins 1860). It is entirely plausible that Joseph Smith III or a member of his family, had the CDV made from an earlier image of Joseph Smith. The advantage of having a CDV copied from a daguerreotype can be demonstrated by viewing an authenticated 1845 daguerreotype of Emma Smith (Joseph Smith’s wife) and her son David Hyrum Smith (Joseph Smith’s son) and a CDV (Figure 2). The daguerreotype has degraded to the point where the image is almost unrecognisable, this occurs due to the chemical nature of the daguerreotype with time and environmental conditions unfavourable to preservation (Švadlena 2014).

Fig. 2. A paper CDV copy of Emma and David Smith [left, courtesy of the Community of Christ] taken from the original 1845 daguerrotype [right, Collection of John Hajicek, Mormonism.com]

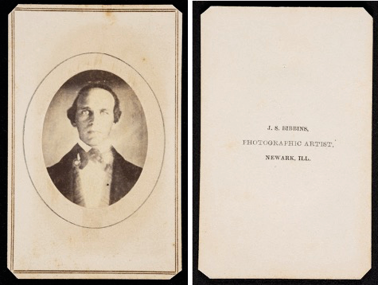

To further authenticate the date of the CDV and connections with Joseph Smith Jnr, the clothing was analysed. Only a few examples of clothing worn by Joseph Smith Jnr have survived the past 176 years since his death. The Pioneer Memorial Museum in Utah is in possession of a collar and a vest belonging to Joseph Smith Jnr (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Popped down collar (top) and vest with horizontal stripes (bottom) both belonging to Joseph Smith Jnr. Courtesy of the International Society of Daughters of Utah Pioneers

The collar is a ‘popped down’ collar, where the top of the collar is elongated and is folded down over a neck/bow tie, much like the one seen in the CDV of the unknown man. The vest has blue, black and white horizontal stripes on the front. The CDV shows a man wearing both a popped down collar and a vest with horizontal stripes visible under the lapels of his jacket. Colour cannot be determined as the photo is monochrome but it is obvious that there are different shades of stripes on the jacket pictured in the CDV. This is not evidence enough to show that the unknown man in the CDV and Joseph Smith Jnr are one and the same but it does provide further authentication of the man in the photograph as being from the 1840s due to the similar clothing styles. It also does not provide evidence against the possibility that Joseph Smith Jnr is the man in the CDV.

As previously mentioned, the Dibble death mask (Figure 4) is considered the most reliable representation of the face of Joseph Smith Jnr. Weber (2009) confirms this by demonstrating the facial proportions of the death mask, matching the death mask with outline drawings of Joseph’s facial profile drawn by Sutcliffe Maudsley in 1842 when they drew Joseph from life. Multiple images of the death mask were taken in person by DH showing all angles for facial comparison.

Fig. 4. ‘Dibble’ death mask of Joseph Smith, on display at the Museum of Church History and Art in Salt Lake City. © D.Hatfield

Images of the ‘Dibble’ death mask of Joseph Smith Jnr (Figure 4) and the CDV of a man (Figure 1) are compared using morphology and superimposition to establish any similarities or differences. Morphological analysis is conducted using a set of standardised categorical scales to describe various anatomical features of the face and head. Scales were derived from Gabriel and Huckenbeck (2013) and Iscan and Steyn (2013). For each feature, a set of categories exists which can describe the shape, size, presence/absence, colour or position of anatomical traits. For example a person’s face shape can be classified according to the following ten categories: ellipitical, round, oval, pentagonal, rhomboid, square, trapezoid, wedge shaped, double concave, asymmetrical. These scales use stardardised verbal descriptions and images of the categories to avoid miscategorisation/misinterpretation of anatomical traits. As well as categorising anatomical traits using standardised categories which capture morphology (size, shape etc.), unique identifiers and levels of symmetry/asymmetry are considered. The facial analysis was performed independently by two trained experts (MH and TL) in order to reduce potential bias. Analysis of the death mask was conducted by MH, while the analysis of the photograph was conducted by TL. After all descriptions/categorisations of traits were performed, the findings of MH and TL were compared. The features that could not be reliably compared between the CDV and the death mask were excluded, for example the death mask was photographed from various angles which allowed more features to be seen, however the CDV only presents the anterior view where some features could not be assessed. It is standard when conducting a facial comparison that if any anatomical differences are found between the two subjects then it must be concluded that they are not the same person. These differences do not include those that can be explained by lighting, camera angle and environmental differences which could alter anatomy between images eg. the effects of aging over time.

Morphology is the primary method used in this case as it was the most appropriate method for the types of images the authors had access to. However, as a secondary form of analysis a facial superimposition was conducted to show the alignment of anatomical points of the face between the man in the CDV and the death mask. As superimposition can result in bias (Houlton and Steyn 2018) it should only be considered a secondary source to further illustrate similarities or differences. The following standardised anatomical points (Martin and Saller 1957) were identified on both images and then the images were overlayed to show the alignments of these points: nasion (the deepest point of the root of the nose in the midline), subnasale (the point where the nasal septum meets the philtrum), stomion (the midpoint of the occlusal line between the lips), gnathion (the most inferior point on the body of the mandible in the midsagittal plane).

The similarities between the death mask and the CDV were compiled after the independent analysis of each, conducted by MH and TL. Both experts agreed on 16 similarities and found 3 differences. Morphological points of comparison are presented in table 1 and figure 5.

Due to the long time it took for older cameras to capture the image of a person, people were often photographed with little facial expression, this allowed for better comparison as the neutral facial expressions of the man in the CDV and that of the death mask matched. Both the unknown man in the CDV and Joseph Smith Jnr. have a very high and broad forehead, this is further emphasised by the concave shape of the frontal hairline on the superior aspect of the head. Laterally, the hair moves more anteriorly to the temporal region. The superior border of the hairline can be seen in both the CDV and the death mask, however, lateral extent of the hair cannot be seen in the death mask. This is not to say that it was not present, but the mask was not moulded to the point where the hair is present on the image.

Table 1. Categories of facial traits showing similarities and differences between the man in the CDV and the death mask of Joseph Smith

| Similarities | |

| 1 | Cheek bones: Prominent |

| 2 | Forehead height: High |

| 3 | Forehead width: Broad |

| 4 | Frontal hairline shape: Concave |

| 5 | Eyebrow shape: Straight, tapering on the left eye |

| 6 | Palpebral slit: Horizontal with the left eye drooping laterally |

| 7 | Nasion depression: Trace |

| 8 | Nose width: Medium |

| 9 | Nasal root: High |

| 10 | Septum tilt: Horizontal |

| 11 | Nostril position: Inferior |

| 12 | Lip thickness: Average |

| 13 | Relative lip size: Lower lip more prominent with thin upper lip |

| 14 | Upper lip shape: Flat |

| 15 | Lower lip shape :Flat |

| 16 | Chin shape: Round |

| Differences | |

| 17 | Face shape: rhomboid to wedge shape: there is little difference between these two face shapes, both are longer than they are wide. The rhomboid shape, has a slight protrusion laterally at the level of the cheek bones while the wedge shape does not. |

| 18 | Eyebrow thickness: the eyebrows on the death mask are thinner (possibly due to the casting process of the mask) |

| 19 | Philtrum prominence: the philtrum of the death mask is less prominent (possible due to casting process) |

| 20 | Mouth corners: the man in the CDV has straight mouth corners while the death mask has the left corner that is orientated downwards and a right that is orientated upwards (possibly due to gravity and the position of the body when the mould was taken) |

Fig. 5. Visual references for the similarities between the unknown man in the CDV and the death mask of Joseph Smith. Numbers like in Table 1

Although the similarities presented in Table 1 are in standardised categorical scales for facial features, there are some categories which cannot fully describe anatomical traits, especially unique identifying features and asymmetry of the face, therefore, these are discussed in addition to standard morphology. The eyebrow shape is straight, however, the left eyebrow of the man in the CDV is shorter than the right brow and it tapers laterally. As well as this, the left eye lid slopes laterally partially closing the eye, while the upper lid of the right eye is consistently widely open. Thus, the entire left eye and its brow are asymmetrical when compared to the right. The left eye is located slightly inferior compared to the right eye. The asymmetry of the eyes, the tapering of the left brow and the slope in the upper left eyelid are most likely a result of trauma to the left temple. The death mask shows both the tapering of the left eyebrow and the asymmetry in the position of the eyes, however, the sloping of the left upper eyelid cannot be compared as the eyes are closed. Although there is a high brightness of the photographic image on the left side of the man in the CDV, the authors are confident that the missing lateral aspect of the eyebrow is not a consequence of photo-exposure. The asymmetry of the position of the eyes on the CDV cannot be questioned.

Both faces have similarities in their descriptions, namely, they are both longer than they are wide, with the width of the face reducing inferiorly. The difference between the rhomboid and wedge shapes is that the widest part of the face in the rhomboid is the zygomatic width (cheek bones) whereas the wedge shape has a wider gonial region (angle of the mandible). Both authors agreed that the cheek bones were prominent. The mask does not reach back far enough to include gonions, hence a possible difference in observation. Thus the differences in face shape are considered insignificant. The eyebrows on the death mask are thinner than those of the man in the CDV, this could be due to the moulding process whereby only the thickest parts of the eyebrows were captured in the mould. The hair on the outline of the eyebrows may not have been captured in the mould as these hairs are often thinner than in the middle. The philtrum on the death mask is less prominent ie. less concave, this could be due to the post-mortem change in the skin of the face (sagging and flattening). The man in the CDV has straight corners of the mouth while the death mask has a left corner pointing downwards and the right corner pointing upwards. Joseph Smith Jnr would have been in the prone position when the death mask mould was taken and the effects of gravity may have acted differently upon the mouth corners depending on the evenness of the surface that the table was on or exact position of his head.

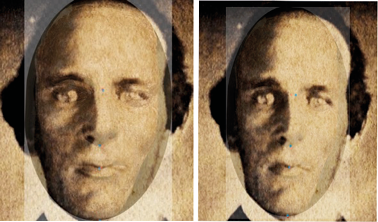

Fig. 6. Superimposition of CDV and the images of the death mask belonging to Joseph Smith Jnr

Figure 6 shows the superimposition of the CDV and the image of the death mask with the anatomical points identified. The anatomical points align with each other and there are no significant differences between points. As there are no differences in the alignment of points and the findings of the morphological analysis, the man in the CDV cannot be ruled out as potentially being Joseph Smith Junior.

Joseph Smith Jnr kept a personal journal throughout his life and wrote many letters to his family and friends. In his writings, he details multiple instances where he was subject to trauma, any one of these incidents could have resulted in the trauma to the left side of the face that was described from the photograph and potentially captured in the death mask. The most traumatic incident described by Joseph Smith Jnr occurred between the 25th and 26th March 1832. Joseph was badly beaten and tarred, fearing for his life he later wrote ‘I learned that they had concluded not to kill me, but pound and scratch me, well tear off my shirt and drawer and leave me naked’ (Smith 1805–1834). He goes on to describe how the men who attacked him had tarred up his face and body. Another significant experience is dated circa 18th December 1835 when Joseph Smith Jnr wrote a letter to his brother William Smith, describing a physical altercation between the two men, Joseph wrote ‘…abuse, anger, malice, hatred, and rage, are heaped upon me, by a brother; and with marks of violence upon my body, with a lame side, I left your habitation bruised and wounded…’ (Smith 1835). These are just two examples of physical abuse that Joseph had endured in his lifetime and as mentioned previously, could have lead to the trauma on the left side of the face which is responsible for the asymmetry of the eye region and missing lateral aspect of the left eyebrow. Ptosis is a condition that occurs when the muscles which raise the eyelid, or their nerve supply, are damaged, namely the levator palpebrae superioris or the superior tarsal muscle (Srinath et al. 2012). Both of these muscles function to elevate the upper eyelid, thus, any damage would cause the eyelid to fall. Ptosis can have different levels of severity, in the extreme the eyelid can cover the pupil, in the less severe cases, only minor drooping of the eyelid is seen (Finsterer 2003). The man in the CDV has minor ptosis as the entire pupil is visible. The missing lateral aspect of the left eyebrow may also be a result of trauma, namely, scarring which leads to the loss of hair over the scar site. However, this cannot be confirmed as the CDV has a high brightness (overexposure) on the left side, which does not allow fine details such as scars to be seen. There is a sign of trauma (a scar) on the death mask at the site of the tapering eyebrow, the substance used to create the mask is roughened at the lateral part of the left eyebrow. This can either be from scarring in real life, or a consequence of the moulding process or damage to the mask itself.

As previously discussed, many of the historical descriptions of Joseph Smith’s appearance are considered unreliable as many are contradictory and do not focus on anatomy. However, there were some anatomical details that were consistent in the historical record, these include: thin lips, prominent nose, oblong/oval face, large forehead without a furrow, retreating hairline, eyes set back in the head (McCarl 1962). This list of features was investigated after the authors conducted their analysis, both MH and TL agree that the man in the CDV and the death mask of Joseph Smith have a large and retreating forehead without a furrow. The ‘retreating’ forehead refers to the hairline being set back more superoposteriorly, which is further emphasised by the concave shape (not described in the historical records). Unfortunately, the nasal profile could not be compared as the CDV is taken in anterior view. According to our analysis, the lip thickness of both men is medium. The eye position in the head was not analysed as part of the standard classification system used but both MH and TL agree that the eyes are ‘set back’ in the head in both men.

Although the authors disagreed on the face shape between the man in CDV and the death mask, both the rhomboid and wedge shape allocated by the authors share similarities with the oval/oblong face shape in that they are both longer than they are wide, giving the appearance of elongation. It needs to be considered that the death mask did not encompass the entire extent of the face, just its anterior part, while the CDV, by the obvious nature of the antero-posterior projection of the entire head and face of an individual, depicted the full extent of the most lateral parts of the face.

There were some limitations in the current analysis. Unfortunately, the CDV is singular and only shows the man from the anterior view. This limited some morphological analyses, namely those that can be observed best from the lateral view, ie. nose projection. The death mask was photographed from multiple angles, including anterior, lateral and superior views which allowed analysis of more features, however, without comparison with the CDV, these were of little use.

Porter and Doran (2000) discuss the usefulness of facial comparisons in the positive identification of individuals, they suggest a holistic approach which includes analysis of the following, unique identifiers (scars, moles etc), morphology (form, size and shape of facial characteristics), facial symmetry (or asymmetry) and anthropometric analysis. Porter (2009) claims that without any evidence of unique identifying features, a positive identification would be most inappropriate. All methods in the holistic approach proposed by Porter and Doran (2000) have been considered in this case except for anthropometry for reasons already discussed, namely, its unreliability in the absence of a scale on the photograph (Houlton and Steyn 2018). In this case, there were morphological similarities, a degree of unique facial asymmetry and a unique identifier in the lateral aspect of the eyebrow (a scar). However, the scarring could not be confirmed due to image quality and inconclusive appearance of trauma on the death mask. There were no moles, other scars or other unique identifiers on either the man in the CDV or the death mask, the absence of which neither confirms nor denies identification. The differences that were present were minor and could be explained by casting/photographic methods. The superimposition showed no significant differences between the man in the CDV and the death mask.

It is not known how many times the actual Joseph Smith Jnr. was photographed. The CDV we have analysed is undoubtedly a technical copy of a daguerreotype of a person whose imperfections, especially related to the left eye and the left brow, were uncorrected by touch up. These are present in the death mask. There are some full face painted portraits claiming to be Joseph Smith Jnr which are free hand artistic reproductions of some unknown image of the person (McCarl 1962) and as such are likely to be biased towards perfect symmetry and the lack of any disfigurement, especially when and if the artists tried to depict an idealised religious leader.

In conclusion, the authors suggest that there is a high degree of anatomical similarity between the man in the CDV and the death mask of Joseph Smith Jnr, however, without an unquestionable unique identifier or authentication of the original daguerreotype, the results of this analysis remain inconclusive, without, however, ruling out the possibility of this being a photograph of Joseph Smith Jnr the American prophet.

Data Availability Statement

No specific data, beyond images included in the paper were used, thus nothing that can be made available exists.

Conflict of interest

The two authors who conducted the facial analysis (TL and MH) would like to declare that they are not affiliated with the LDS faith and thus had no vested interest beyond scientific inquiry in the results and conclusions of this paper.

Authors’ contributions

DH formulated the hypothesis and provided historical information, TL designed and conducted morphological comparison and drafted the text, MH helped with morphological comparison and conducted superimposition. All authors edited the text.

Data availability

Data for this study consist of the photograph analysed and photographic images of the face mask. Copies of both are presented as figures in this paper. Historical information can be obtained from DH debiann25@gmail.com.

* Corresponding author: Maciej Henneberg, Anatomy and Pathology, School of Biomedicine, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide SA 5005; e-mail: maciej.henneberg@adelaide.edu.au

Bibbins JS. 1860. United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Big Grove, Kendall, Illinois; Page: 73; Family History Library Film: 803194. Retrieved from https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryuicontent/view/37536705:7667?tid=&pid=&queryId=fc42271eb2a9bb13e3813239ce17546b&_phsrc=jSI7&_phstart=successSource [Accessed 1 July 2021].

Burstow S. 2016. The Carte de Visite and Domestic Digital Photography. Photographies 9(3):287–305, https://doi.org/10.1080/17540763.2016.1202309

Finsterer J. 2003. Ptosis: Causes, Presentation, and Management. Aesth Plast Surg 27:193–204, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-003-0127-5

Gabriel P, Huckenbeck W. 2013. Identification of the living. In: Encyclopedia of forensic sciences (2nd edition). Eds. Siegel, JA, Saukko, PJ, Houck, MM. Academic press. 97–105.

Gayler GR. 1957. Governor Ford and the death of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. JISHS 50(4):391–411.

HoultonTMR, Steyn M. 2018. Finding Makhubu: a morphological forensic facial comparison. Forensic Sci Int 285:13–20.

Iscan MY, Steyn M. 2013. The Human Skeleton in Forensic Medicine. Charles C Thomas. Springfiled, IL.

Lucas T, Henneberg M. 2015. Are human faces unique? A metric approach to finding single individuals without duplicates in large samples. Forensic Sci Int 257:514-e1–514e6.

Lucas T, Kumaratilake J, Henneberg M. 2016. Metric identification of the same people from images – how reliable is it? J Anthropol 2016:1–10.

Martin R, Saller K. 1957. Lehrbuch der Antropologie, Gustav Fischer, Stuttgart, Germany.

McCarl WB. 1962. The Visual image of Joseph Smith. (Dissertation, Brigham Young University).

Moreton R, Morley J. 2011. Investigation into the use oof photoanthropometry in facial image comparison. Forensic Sci Int 212:231–237.

Porter G. 2009. CCTV images as evidence. Aust J Forensic Sci 41(1):11–25.

Porter G, Doran G. 2000. An anatomical and photographic technique for forensic facial identification. Forensic Sci Int 114(2):97–105.

Quinn DM. 1976. The Mormon succession crisis of 1844. BYU studies quarterly 16(2):187–233.

Romig R, Macay L. 2022. Hidden things shall come to light: the visual image of Joseph Smith Jr. John Whitmer Historical Association 42(1), https://www.jwha.info [Accessed 1 July 2021].

Scoleri T, Lucas T, Henneberg M. 2014. Effect of garments on photoanthropometry of body parts: Application of stature estimation. Forensic Sci Int 237:1–12.

Smith J. 1835. Letter to William Smith. The Joseph Smith Papers, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT, United States, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/letter-to-william-smith-circa-18-december-1835/5 [Accessed 18 January 2021].

Smith J. 1842a. 2nd November 1838-31st July 1842. The Joseph Smith Papers, Journal, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT, United States. https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-1838-1856-volume-c-1-2-november-1838-31-july-1842/522 [Accessed 1 July 2021].

Smith J. 1842b. Journal, December 1841-December 1842. The Joseph Smith Papers , Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT, United States. https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/journal-december-1841-december-1842/82#XB7538EB9-FC09-4743-8FA3-B2226C784F11 [Accessed 1 July 2021].

Smith J. 1844. Journal, December 1842–1844; March-June 1844. The Joseph Smith Papers, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT, United States. https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/journal-december-1842-june-1844-book-4-1-march-22-june-1844/106 [Accessed 3 July 2021].

Smith J. 1979. The memoirs of Joseph Smith III (1832–1914). Herald Publishing House, Independence, Missouri.

Smith J. 2015, The Joseph Smith Papers, Journals, V.3, May 1843-June 1844. Church Historian’s Press, p. 238. https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/journal-december-1842-june-1844-book-4-1-march-22-june-1844/103 [Accessed 3 July 2021].

Srinath N, Balaji R, Basha MS. 2012. Ptosis correction: a challenge following complex orbital injuries. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 11(2):195–199, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12663-011-0300-3

Svadlena J. 2014. Daguerrotype – the first ever practically used photographic technique Daguerrotype – the first ever practically used photographic technique. Koroze a Ochrana Materiálu 58(2):59–64.

Taylor J. 2017. Witness to the Martyrdom: John Taylor’s Personal account of the last days of the Prophet Joseph Smith. 2nd Edn. Deseret Book. Salt Lake City, Utah.

The Diary of Joseph Smith (1805–1834) [diary] 1832 March, p. 205–207 in The Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-1838-1856-volume-a-1-23-december-1805-30-august-1834/213 [Accessed 18 January 2021].

The Saints Herald (1879), Volume 26, pg. 254 Plano, Illinois. August 15th, 1879. https://archive.org/details/TheSaintsHerald_Volume_26_1879/page/n253/mode/2up [Accessed 18 January 2021].

Weber CG. 2009. Skull and crossed bones: A forensic study of the remains of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. Mormon Historical Studies, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Received: 4.11.2022; Revised: 1.12.2022; Accepted: 2.12.2022