INVOLVEMENT OF DIGITAL PLATFORMS IN THE PROCESS OF PAYMENT OF ACCOMMODATION TAX IN SLOVAKIA – THEORY VS. REALITY[1]

Anna Vartašová *

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1366-0134

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1366-0134

Karolína Červená *

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4900-6510

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4900-6510

Abstract. Digitization in the field of taxation represents one of the possible ways of improving the quality and increasing the transparency of this process. We can conclude that, in Slovakia, the potential of digitization for streamlining tax processes as well as increasing taxpayers’ satisfaction is indicated. One of the elements of the tax system where such an aspect is identified is the accommodation tax, where the recent amendment of the Local Taxes Act of 2021 made digital platforms’ operators directly involved in the process of collecting and paying this tax. In this paper, the authors present partial results of their primary research aimed at a critical evaluation of the current state of the transfer of the obligation to collect accommodation tax from the accommodation provider to digital platform operators in the Slovak Republic. The authors came to the conclusion that despite the effort of the legislator to solve a specific aspect of the activity of digital platforms (in relation to the payment of accommodation tax), the amendment of the legislation did not bring about the desired change in application practice and the new legal regulation is not actually applied in practice. In our opinion, the reason for this state of affairs is, on the one hand, the ambiguous wording of the legislative text, from which the actual transfer of the tax collection obligation to the platform operators is questionable, and, on the other hand, only a minimal reduction of the administrative burden of accommodation providers when applying this new regime.

Keywords: digital platforms, local taxes, tourist taxes, accommodation tax, Slovak Republic

ZAANGAŻOWANIE PLATFORM CYFROWYCH W PROCES PŁATNOŚCI PODATKU NOCLEGOWEGO NA SŁOWACJI – TEORIA VS. RZECZYWISTOŚĆ

Streszczenie. Cyfryzacja w dziedzinie opodatkowania stanowi jeden z możliwych sposobów poprawy jakości i zwiększenia przejrzystości tego procesu. Możemy stwierdzić, że na Słowacji istnieje potencjał cyfryzacji w zakresie usprawnienia procesów podatkowych, a także zwiększenia satysfakcji podatników. Jednym z elementów systemu podatkowego, w którym zidentyfikowano taki aspekt, jest podatek od zakwaterowania, w którym niedawna nowelizacja ustawy o podatkach lokalnych z 2021 roku sprawiła, że operatorzy platform cyfrowych są bezpośrednio zaangażowani w proces pobierania i płacenia tego podatku. W niniejszym artykule autorzy przedstawiają częściowe wyniki swoich badań wstępnych mających na celu krytyczną ocenę obecnego stanu przeniesienia obowiązku zapłaty podatku od zakwaterowania z dostawcy zakwaterowania na operatorów platform cyfrowych w Republice Słowackiej. Autorzy doszli do wniosku, że pomimo wysiłków ustawodawcy zmierzających do uregulowania konkretnego aspektu działalności platform cyfrowych (w odniesieniu do płatności podatku od zakwaterowania), nowelizacja przepisów nie przyniosła pożądanej zmiany w praktyce stosowania, a nowa regulacja prawna nie jest faktycznie stosowana w praktyce. Naszym zdaniem przyczyną takiego stanu rzeczy jest z jednej strony niejednoznaczne brzmienie tekstu legislacyjnego, z którego wynika wątpliwość co do faktycznego przeniesienia obowiązku poboru podatku na operatorów platform, a z drugiej strony jedynie minimalne zmniejszenie obciążeń administracyjnych podmiotów świadczących usługi noclegowe przy stosowaniu nowego reżimu.

Słowa kluczowe: platformy cyfrowe, podatki lokalne, podatki turystyczne, podatek od noclegów, Republika Słowacka

1. INTRODUCTION

Technological progress in tax administration has been observed in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe already earlier (Nykiel, Kukulski 2017, 28), but the digitalisation in the field of taxation in Slovakia can be considered a not-yet-completed transformation process (Vartašová, Treščáková 2025), involving the use of digital technologies to improve the quality of administrative tax procedures and services. It provides benefits that can facilitate and streamline processes for individuals (citizens, entrepreneurs) (Mates, Smejkal 2012), but also for public administration (including municipalities) (Andraško 2022; Šebesta et al. 2020), while the implementation of digitalisation in taxation can be identified in the form of electronic delivery and filing of tax returns; tax collection (e.g. also with the help of digital platforms); transparency, or accessibility of information (e.g. in the form of digital statements; notifications helping taxpayers to ensure that they are informed promptly of their obligations and possible arrears) with impact in terms of eliminating potential errors (e.g. automatic tax calculation tools that take into account current tax rules); integration of tax software with accounting and financial systems (e.g. e-cashier); and fraud protection (the potential to use advanced analytical tools and big data technologies to identify patterns and irregularities that could indicate tax fraud or evasion). This is only one side of the coin and the consequences of the digitalisation in general are more complex (Štrkolec 2023; Popovič 2019).

With the increased use of information technology, another element of digitalisation (in the form of digital platforms) has also been included in the provision of short-term accommodation (search, intermediation, booking with/without payment, as well as taxation process), where we encounter the constantly developing activities of the so-called OTAs (Online Travel Agencies), i.e. digital platforms intermediating, among others, accommodation (see in more detail Csach, Jurčová 2023, 8 et seq. or Mazúr 2019).

In many states (legal regimes), the problem is the determination of the legal nature of such entities, where the activity of a particular platform determines the possibility of specific legal regulation (Frydrychová 2017, 250; Domurath 2018). Simić (2022, 22) stresses that “the digital platform itself, unlike its operator, does not have legal personality. For this reason, a digital platform can be likened to a permanent establishment in the tax area rather than to a taxable entity”, which corresponds with the current legislative definition of a permanent establishment in Slovak legislation (Act No. 595/2003 Coll., Income Tax Act). The agenda for the sharing economy identifies platforms as intermediaries that connect providers with users and facilitate transactions between them. European Commission (2016) characterises online platforms as software facilities offering two- or even multi-sided marketplaces where providers and users of content, goods and services can meet.

The platforms have in many cases outgrown their role as intermediaries, though (Malachovský 2022, 10–12; Vartašová, Červená, Olexová 2022), and even the negative impacts of their activities at the local level of cities can be highlighted. For example, the European Cities Alliance on Short-Term Rentals published an open letter on the need for legislative action to tackle illegal short-term rentals on 13 July 2022 (Eurocities 2022). In addition, the increased use of digital platforms to provide services and sell goods poses a higher risk of tax evasion (Priateľová 2021, 293), not even mention the conduct of digital giants leading to significant tax evasion problems (Štrkolec, Hrabčák 2022, 163).

The impact of digital platforms can be identified at the level of local budgets, as well, especially in the context of so-called tourist taxes. These are usually imposed as local taxes and most frequently applied as the “occupancy taxes”, equivalent to a bed tax or tourist tax (Radvan 2020), with different designations: local taxes or fees for accommodation (SK – accommodation tax “daň za ubytovanie”), for stay (CZ – fee for stay “poplatek z pobytu”), spa taxes/fees (PL – spa fee “opłata uzdrowiskowa”) or simply tourist taxes (HU – “idegenforgalmi adót”) or local fees (PL – “opłata miejscowa”) (also Pahl et al. 2024).

The importance of local taxes varies at the national level (Radvan 2020). In the Slovak Republic, the accommodation tax is currently fiscally insignificant, which is documented by its share in the revenues from all local taxes and fees, which has ranged from 1.4% to 2.8% in the last ten years, representing an average of 0.29% of the current municipal revenues. However, given that not all municipalities impose this local tax, its importance in individual cases is greater than on a national scale. For example in Bratislava, the capital of the Slovak Republic, it amounted to between 1.3% and 1.6% of total municipal revenues before the period of the COVID-19 pandemic (1.03% on average over the last 10 years).[2] Thus, from an individual local perspective, it makes sense to address the issue of local accommodation tax, especially in the context of evasion of local taxes that exist due to the greater anonymity of accommodation providers for whom these services are mediated by digital platforms. Based on the results of our pilot research (survey) conducted in the city of Košice (the second largest city in the Slovak Republic) in 2023, we estimate that less than half of the accommodation facilities that provide accommodation in Košice fulfil their local tax obligation. It was precisely at the elimination of evasion of this tax that the 2021 amendment to the accommodation tax legislation in the Slovak Republic was aimed; the amendment established the status of the digital platform as a representative of the accommodation providers, i.e. as an intermediary in the payment of the accommodation tax to the municipality.

Based on the above, the authors aim to identify the contribution of the new legislation reflecting the activity of digital platforms in the field of accommodation intermediation in the context of the local accommodation tax by answering the research question of whether the adoption of the new accommodation tax legislation focused on digital platforms had a positive effect in the context of transferring the obligation to pay accommodation tax from accommodation providers to digital platform operators in the municipalities and cities of the Slovak Republic. This is because the authors identified a research gap in their previous research (Vartašová, Červená, 2023) on this specific topic – tax aspects of digital platforms’ activities in SR in relation to the accommodation tax, as only Simić (2022), Mazúr (2019) and partly Sidor et al. (2019) have so far specifically addressed this topic. Other aspects of the issue, possibly in other countries, have been addressed by several authors, though (with a different geographic or tax focus, e.g. Bonk 2019; Cibuľa et al. 2019; Klučnikov, Krajčík, Vincúrová 2018; Kóňa 2020; Janovec 2023; Radvan, Kolářová 2020; Szakács 2021; Hučková, Bonk, Rózenfeldová 2018; or non-tax aspects, e.g. Rudohradská, Treščáková 2021; Kubovics 2023). The authors used the methods of direct surveying (questionnaire) and analysis of legislative text.

2. REFLECTION OF DIGITAL PLATFORMS IN SLOVAK TAX LEGISLATION

Accommodation tax is a facultative local tax regulated by the Act No. 582/2004 Coll. on Local Taxes and Local Fee for Municipal Waste and Small Construction Waste, as amended (“Local Taxes Act”), subject to which is a paid temporary accommodation of up to 60 overnights (i.e. only short stays) in an accommodation facility, which is defined by the law.[3] The character of the stay is not reflected, thus, not only tourists are affected by the tax (Pahl et al. 2024). The rate determination is fully in the competence of a particular municipality with no upper or lower statutory limits. It may be set differently for different parts of the municipality or its cadastral areas, which enables the municipality to take into account recreational or tourist zones and other locations of the municipal area (Vartašová 2021). The accommodated person bears the tax but it is collected and remitted to the municipality by the accommodation provider[4] (designated as “tax remitter”), where an important change occurred by Act No. 470/2021 Coll., with effect from 11 December 2021, to reflect the problem of digital platforms operation. It was the implementation of a new institute – a representative of the tax remitter, who is defined as

a natural or legal person who arranges for the provision of paid temporary accommodation between the tax remitter and the taxpayer through the operation of a digital platform offering facilities in the territory of the municipality providing paid temporary accommodation.

The municipality may enter into an agreement with the tax remitter’s representative on the details of the scope and manner of keeping records (of natural persons to whom remunerated temporary accommodation had been provided) under Art. 41a para. (2) of the Local Taxes Act for the purposes of paying the tax, the manner of collecting the tax, the details of the tax payment certificate, the time limits and the manner of payment of the tax to the municipality.

The tax remitter is obliged to notify that “instead of him, the tax is collected in part or in full by the tax remitter’s representative who undertakes the performance of the tax obligation on behalf of the tax remitter”; thus, his “tax base according to Art. 39 is reduced by the tax base which his representative has undertaken on behalf of the tax remitter.”

The tax remitter’s representative shall notify the municipality of the tax base pursuant to Art. 39 within the time limit and in the manner prescribed by the generally binding regulation. The tax remitter’s representative shall collect the tax from the taxpayer on behalf of the tax remitter and shall pay it into the account of the tax administrator. The payment to the account of the tax administrator shall be deemed to be the tax payment.

The existence and activity of digital platforms were ignored by tax legislation in Slovakia until 2017 when the first change concerning income tax was adopted. It was the amendment by Act No. 344/2017 Coll., which, with effect from 1 January 2018, added the definition of a digital platform (“hardware platform or software platform necessary for the creation of applications and the administration of applications”) into Art. 2 of the Income Tax Act, in the context of the extended definition of a permanent establishment, where “the performance of an activity with a permanent establishment in the territory of SR shall be deemed to include the repeated intermediation of transport and accommodation services, including via a digital platform” (Vartašová, Červená, Olexová 2022, 436). The legislative measure, however, was subject to some relevant criticism (Galandová, Kačaljak 2019 or Cibuľa et al. 2019). A PE had to be registered by the end of the calendar month following its creation and if it did not meet this obligation, the tax administrator registered it automatically. At the end of 2022, there were 10 platforms registered (Simić Ballová 2023, 120). Moreover, the income payer (i.e. the accommodation provider) was obliged, under Art. 43 para. 2 of the Income Tax Act, to withhold tax at the rate of 19% or 35%[5] on the payment for the services of using the intermediary platform (Vartašová, Červená, Olexová 2022, 436). Such regulation was criticised because the accommodation providers have no real possibility to withhold the tax and would have to pay the tax from their funds and then, eventually, claim it from the platform operator (Sme.sk 2018). A symbolic legislative amendment reflecting the existence of electronic platforms was also done since January 2018 as regards the VAT regulation.[6]

Other legislative changes in relation to digital platforms have been done to the Local Taxes Act, specifically the Accommodation Tax, by the aforementioned amendment in 2021.

3. RESEARCH

In the context of the above changes in the legal regulation, the authors conducted their own primary research aimed at determining the state of application of the new legal regulation of the accommodation tax in practice. For this purpose, the authors directly queried all municipalities in the Slovak Republic with the city status (141 cities). The survey was conducted between 14 March 2024 and 30 April 2024 (when the last response was received) in two rounds (the cities that initially did not respond were contacted again on 10 April 2024), by direct approach via the officially published contact e-mail addresses of the municipalities (cities) concerned. Four questions were raised: 1. Do you apply the accommodation tax? 2. Does any online platform remit accommodation tax to your municipality on behalf of any accommodation tax remitter (accommodation facility)? 3. Has any accommodation tax remitter notified your municipality that a representative of him (i.e. the online platform) will collect the tax instead of the accommodation tax remitter in line with Art. 41a para. 3 of the Local Tax Act? 4. Do you have an agreement with any representative of the tax remitter (platform) on the details of the scope and manner of keeping records for the purposes of payment of the accommodation tax under Art. 41c of the Local Tax Act, or any other similar agreement? The results were processed using graphical and exploratory analysis.

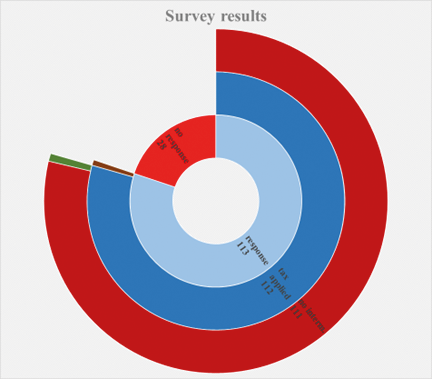

As can be seen from Figure 1, we received 113 responses out of a total of 141 cities, representing an 80.14% questionnaire return rate. Of these, 112 municipalities indicated that they have an accommodation tax in place (and only one municipality responded negatively), representing 99.12% of the cities from which a response was received. Of the 112 cities that indicated that they have the tax in place, only one city answered positively to questions 2–4, i.e. that it has an agreement with an online platform for the purpose of paying the tax and that this platform pays the accommodation tax instead of the accommodation establishments for which it arranges accommodation. Specifically, the City of Bratislava has such an agreement with one platform – AirBnB. One other city stated that they had contacted Booking.com but had not yet received any response. Thus, 99.1% of the responding cities have no agreement with any platform for the purpose of paying tax for accommodation facilities and no platform is actually remitting the tax instead of accommodation facilities in these cities.

This result is surprising, as the amendment to the Local Taxes Act in question became effective on 11 December 2021, i.e. 2024 is the third year since the institute of the tax remitter’s representative has been introduced. Nevertheless, almost no city has used it, or perhaps we can conclude that no city has since the only one city with a positive answer (Bratislava) had already concluded such an agreement with the AirBnB platform before the adoption of the amendment in question – in June 2021 (Vartašová, Červená, Olexová 2022), and thus the adoption of the amendment to the Local Tax Act did not have any impact on this case.

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Ensuring the payment (or rather the collection and remittance) of the tax instead of the accommodation facility through a digital platform would be mutually beneficial – it would simplify activities for landlords, for whom it would mean a reduction in the administrative burden, as well as for the local tax administrator, who would be assured of proper and timely payment of local tax; e.g. at the time of the conclusion of the agreement on collection of accommodation tax between the city of Bratislava and AirBnB, the city estimated a benefit of EUR 0.6 million per year (bratislava.sme.sk 2021). However, the current reality does not correspond to the intended legislative effect.

The presented results lead us to the need for further investigation to identify the factors/causes for this condition. It is primarily necessary to analyse the legal regulation itself.

One of the possible reasons for not applying the new legislation may be the wording of the normative text. The legislator defined who is the tax remitter’s representative (Art. 38 para. 3), the duty of the tax remitter to notify the municipality that the tax is being collected in part or in full by his representative, who takes over the fulfilment of the tax obligation (Art. 41a para. 3), notification and other duties of the tax remitter’s representative towards the municipality as a tax administrator and the possibility of the municipality to conclude an agreement with the tax remitter’s representative for this purpose (Art. 41c). Yet, what the legislator neglected, is to enshrine the clear obligation of the platform to undertake the collection and remittance of local tax and left this ambiguous, i.e. as if based on an agreement between the platform and the accommodation facility, for which the fulfilment of the tax obligation should be taken over.

In our opinion, the wording “who undertakes the fulfilment of the tax obligation on behalf of the tax remitter” is very unfortunate, since the grammatical meaning of the connection “to undertake an obligation” presupposes one’s own action, i.e. the will of the operator to undertake this obligation and other clear legal wording, e.g. that the fulfilment of the tax obligation is transferred to the platform operator by virtue of law or on the basis of conditions set by municipality in the generally binding regulation, would be more appropriate. Another possible interpretation of the current legislation could be that the platform operator takes over the fulfilment of the tax obligation by the notification of the tax remitter to the municipality. The same opinion on the voluntary decision of the platform operator and only the facultative nature of the new institute hold Kubincová and Jamrichová (2022, 285). Simić (2022, 25) holds an opinion about the mandatory collection of tax by the platform operator, which she derives from the provision of Art. 41c, where it is stated that “the representative of the tax remitter collects tax from the taxpayer on behalf of the tax remitter, which he transfers to the account of the tax administrator.” Nevertheless, this sentence, in our opinion, can also be interpreted in the context of the fact that it might be applied only to cases where the representative of the tax remitter actually had taken over the fulfilment of the tax obligation. Another part of legislation supporting the ambiguity of the transfer is the second sentence of Art. 41a para. 4 (“If part or all of the tax liability is fulfilled on behalf of the tax remitter by his representative, the tax base according to Art. 39 is reduced by the tax base that was taken over by the tax remitter’s representative”), which does not make it clear whether the transfer of the duty to the platform is present in all cases when accommodation is intermediated through a platform or only in case when the platform undertook the duty. Račková (2021) even states that without the agreement between the platform operator and the municipality on the terms of fulfilling this duty, there is no option to use this special regime and the same interpretation is provided by the Financial Directorate of SR (2023). However, we do not agree since such an interpretation cannot be followed from the legislative text; moreover, the deadline and manner of this notification duties shall result from the generally binding regulation (Art. 41c). Thus, it is even more important to have these issues regulated by the local law than by this special agreement. Methodological instruction of the Financial Directorate of SR (2023) operates with the ex lege emergence of the platform operator’s obligation, should it intermediate the accommodation, and, in such a case, the accommodation provider is always obliged to report this to the municipality. On the other hand, it states that this regime will be applicable if the agreement between the municipality and the platform operator[7] is concluded, which, altogether, makes no sense to us. A very similar interpretation is anchored in the Explanatory Report to Act No. 470/2021 Coll., Art. 38, stating that “the role of the tax remitter’s representative is conditioned by the decision of municipality” referring to Art. 41c, where, however, not only the possibility to make an agreement between the platform operator and municipality, but also stating the details of payment in the generally binding regulation are set. We believe that from the wording “municipality may conclude an agreement…” it cannot be deduced that this agreement is decisive for the activation of the special regime, but it has to be the generally binding regulation that is decisive. We assume that the current wording of the law does not clearly compel digital platforms to fulfil these obligations, and at the same time, it does not in any way compel the accommodation providers (besides the standard rules) to fulfil their tax obligation. Given that the duties of collecting and remittance of the local tax were (tried to be) shifted from accommodation facilities to digital platforms, in our opinion, mainly to eliminate tax evasion in this area, this measure is obviously ineffective, as there is no change in practice, which is finally confirmed by our research in this paper. Finding no case where the current new regime would be applied may impose the general unawareness what to do and how to interpret the regulation on all the sides (accommodation providers, municipalities, platforms).

Nevertheless, the very fact of non-fulfilment of tax obligations by accommodation providers regarding the accommodation tax is, in its essence, difficult for us to understand, as the tax remitters do not bear this tax, they only collect it from the accommodated guests and remit it to the municipality – for them it is a transaction cost. Thus, it can be considered that the primary factor influencing the cases of non-fulfilment of tax obligations may be the reluctance of accommodation facilities operators to increase their administrative burden by fulfilling registration and record-keeping obligations towards the municipality; Mazúr (2019, 233) is thinking similarly. The tax remitter is obliged to fulfil several administrative obligations for the purposes of this tax. First of all, he must notify the creation and termination of tax liability, the details of which are established by the municipality in a generally binding regulation. Furthermore, he is obliged to keep detailed records of natural persons to whom temporary accommodation was provided for a fee, in the form of a record book (either in paper form or in electronic form). It contains the name and surname of the accommodated natural person, address of permanent residence, date of birth, number and type of identity card (citizen card, passport or other document proving the identity of the taxpayer), length of stay (number of overnight stays) and other records necessary for the correct determination of tax. Should the platform operator undertake the duty of collecting and remitting the tax, it is only part of the burden, however, the current legislative text cannot directly result in the accommodation provider being relieved from other administrative burdens connected with reporting to the municipality (as confirmed by the Financial Directorate of SR 2023). Thus, the new legislation might not be the best motivation for those accommodation providers who have not declared their activities to municipalities before this change as their administrative burden would not be substantially lowered should they “cooperate” with the municipality now. Moreover, the accommodation provider is obliged to notify the municipality of the payment of tax by the platform operator instead of him, nevertheless, we assume that most of the providers are not even aware of such a duty or may not interpret it as a duty (but rather a possibility to use the platform as their representative).

This analysis leads us to the conclusion on the need for a more precise wording of the legislation and general reduction of administrative burden in cases with a high probability of non-compliance from the tax remitters’ (or more generally any taxpayers’) side, should the state want to truly incorporate the digital platforms into the tax collection process.

The potential to contribute to the solution of the problem of non-fulfilment of tax obligations surely has also the Council Directive (EU) 2021/514 of 22 March 2021 amending Directive 2011/16/EU on administrative cooperation in the field of taxation (DAC7), obliging the operators of digital platforms to disclose information about their registered sellers’ transactions to the European tax authorities. In SR, the directive was transposed by Act No. 250/2022 Coll., amending especially the Act No. 442/2012 Coll., effective from 1 January 2023. It introduces the obligation of notifying platform operators to collect and provide the competent authority of the SR with information on notifiable sellers who actively sell goods and provide services (including real estate rentals and accommodation provision).

For the first time in 2024 (until the end of January – for the year 2023), the platform operators were obliged to fulfil the notification obligation regarding the required data, and for these purposes, the necessary forms were assigned to the platform operators established in the Slovak Republic in their personal internet zone on the financial administration portal, while platform operators who are not established in the Slovak Republic had to register in the Slovak Republic or in one of the EU member states (if the conditions defined by law were met). The data that are reported by the platform operators include, for each reportable seller who performed a selected activity involving the rental of real estate, both general information (name, surname, address, date of birth and all assigned identification numbers) and also a financial account identifier (if available to platform operator), the name of the holder of the financial account to which the remuneration is paid or credited (if different from the name of the seller subject to notification), as well as all other available financial identification information relating to this holder of the financial account, further, each Member State in which the notifiable seller is resident; the fees, commissions or taxes withheld or claimed by the reporting platform operator during each quarter of the reporting period; the address of each item on the property list and the relevant cadastral number or its equivalent under the national law of the Member State in which it is located, if assigned; the total remuneration paid or credited during each quarter of the reporting period; and finally, the number of selected activities provided for each property listing and the number of rental days for each property listing during the reporting period and the type of each property listing, if this information is available. This information is provided electronically to the Financial Administration of the Slovak Republic (the competent authority of the Slovak Republic is the Ministry of Finance of the Slovak Republic), so it is crucial how the processes of sharing this information between the financial administration and municipalities, as local tax administrators, will be set up so that the municipalities can also benefit from the new procedural arrangement. Monitoring the application practice and evaluating the benefits of the new regulation by the DAC 7 Directive will be the subject of future follow-up research.

One of the authors’ conclusions is that the current absence of direct involvement of digital platforms providing short-term accommodation in the tax collection process contributes to the failure to use the full potential of this tax or to reduce the potential gap on this tax. For this reason, legislation has already been adopted in many countries, according to which digital platforms participate in the collection of local tax (Airbnb 2024a), even though, positive examples are some platforms such as AirBnB, which participates in this process voluntarily in many cities around the world (Mazúr 2019; Vartašová, Červená, Olexová 2022). Thereby it participates in fulfilling the tax obligations of accommodation providers (Airbnb 2024a) and thus contribute to relieving the burden laid upon the operators of accommodation facilities, especially natural persons renting out their free accommodation capacity, who, as non-entrepreneurs, are often not sufficiently informed about their (tax) obligations or their fulfilment causes them an excessive administrative burden. Perhaps the possible future legislative limitation of the administrative burden laid upon accommodation providers and the raise of awareness about the possibility of involving the online platform in the fulfilment of tax obligations in the Slovak Republic would contribute to the improvement of tax discipline in the area of accommodation tax.

Authors

* Anna Vartašová

* Karolína Červená

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AirBnB. 2024a. “Ve kterých oblastech se o výběr a odvod daně z obsazenosti stará Airbnb?” https://www.airbnb.cz/help/article/2509 (accessed: 29.05.2024).

AirBnB. 2024b. “Airbnb delivers more than $10B in tourism taxes on behalf of Hosts.” March–April 21. https://news.airbnb.com/airbnb-delivers-more-than-10b-in-tourism-taxes-on-behalf-of-hosts/ (accessed: 29.05.2024).

Andraško, Jozef. Martin Daňko. Matej Horvát. Matúš Mesarčík. Soňa Sompúchová. Ján Škrobák. 2022. Regulačné výzvvy e-governmentu v Slovenskej republike v kontexte práva Európskej únie. Praha: Wolters Kluwer ČR.

Bonk, František. 2019. “Zdaňovanie ubytovacích služieb v zdieľanej ekonomike (príklad daňovej regulácie internetovej platformy Airbnb).” In Dny práva 2018 – Days of law 2018. Edited by Eva Tomášková, Damian Czudek, Jiří Valdhans. 60–71. Brno: Masarykova 1univerzita. http://dnyprava.law.muni.cz/dokumenty/48928

Bratislava.sme.sk. 2021. “Airbnb podpisuje s Bratislavou dohodu o výbere dane za ubytovanie.” June 24. https://bratislava.sme.sk/c/22689185/airbnb-podpisuje-s-bratislavou-dohodu-o-vybere-dane-za-ubytovanie.html (accessed: 30.05.2024).

Cibuľa, Tomáš. Tibor Hlinka. Andrej Choma. Matej Kačaljak. 2019. “Digitálna platforma ako stála prevádzkareň.” Právny obzor: teoretický časopis pre otázky štátu a práva 102(2): 155–167. https://www.pravnyobzor.sk/index.php?id=po22019

Csach, Kristián. Monika Jurčová. 2023. “Digitálne platformy a právo, doterajší vývoj a výzvy do budúcnosti.” In Digitálne platform. Edited by Monika Jurčová. 8–15. Bratislava: Slovenská akadémia vied. Veda, vydavateľstvo Slovenskej akadémie vied.

Domurath, Irina. 2018. “Platforms as contract partners: Uber and beyond.” Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law 25(5): 565–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/1023263X18806485

Eurocities. 2022. “Short term rentals: cities ask Europe’s help.” July 13. https://eurocities.eu/latest/short-term-rentals-cities-ask-europes-help/ (accessed: 29.05.2024).

European Commission. 2016. Commission staff working document SWD(2016) 172 final. Online Platforms. Accompanying the document Communication on Online Platforms and the Digital Single Market, COM(2016) 288 final.

Financial Directorate of the Slovak Republic. 2023. “Methodological instruction on accommodation tax according to Arts. 41a to 41d and 104l para. 1 of Act No. 582/2004 Coll. on local taxes and a local fee for municipal waste and small building fees waste as amended.” No. 1/MD/2023/MP. March 7. https://www.financnasprava.sk//_img/pfsedit/Dokumenty_PFS/Zverejnovanie_dok/Dane/Metodicke_pokyny/Miestne_dane/2023/2023.03.07_001_MD_2023_MP.pdf (accessed: 20.05.2024).

Frydrychová, Michaela. 2017. “Uber, Airbnb, Zonky a další, co jsou vlastně zač? Aneb právní povaha subjektů vystupujících v rámci sdílené ekonomiky.” In Sdílená ekonomika – sdílený právní problém? Edited by Jan Pichrt, Radim Boháč, Jakub Morávek. 248–258. Praha: Wolters Kluwer ČR.

Hučková, Regina. František Bonk. Laura Rózenfeldová. 2018. “Collaborative Economy – Open Problems and Discussion (With Regard to Commercial and Tax Issues).” Studia Iuridica Cassoviensia 6(2): 125–140.

Janovec, Michal. 2023. “Airbnb as an accommodation platform and tax aspects.” Studia Iuridica Lublinensia 32(5): 163–180. http://dx.doi.org/10.17951/sil.2023.32.5.163-180

Ključnikov, Aleksandr. Vladimír Krajčík. Zuzana Vincúrová. 2018. “International Sharing Economy: the Case of AirBnB in the Czech Republic.” Economics and Sociology 11(2): 126–137. https://www.economics-sociology.eu/?581,en_international-sharing-economy-the-case-of-airbnb-in-czech-republic

Kóňa, Jakub. 2020. “Sociálno-ekonomické predispozície vybraných európskych krajín pre podnikanie v oblasti ubytovacích služieb prostredníctvom Airbnb.” In Merkúr 2020: proceedings of the international scientific conference for PhD. students and young scientists. Edited by Peter Červenka, Ivan Hlavatý. 119–131. Bratislava: EUBA vydavateľstvo EKONÓM.

Kubincová, Soňa. Tatiana Jamrichová. 2022. Zákon o miestnych daniach a miestnom poplatku za komunálne odpady a drobné stavebné odpady. Komentár. Prague: C.H.Beck.

Kubovics, Michal. 2023. Digitálne marketingové platformy a systémy I. Brno: Tribun EU.

Malachovský, Andrej. 2022. “Možnosti regulácie ekonomiky spoločného využívania.” In Ekonomika spoločného využívania – príležitosť pre udržateľný a konkurencieschopný rozvoj cestovného ruchu v cieľových miestach na Slovensku. Edited by Kristína Pompurová. 8–22. Banská Bystrica: Belianum.

Mates, Pavel. Vladimír Smejkal. 2012. E-government v České republice: Právní a technologické aspekty. Prague: Leges.

Mazúr, Ján. 2019. “Daň za ubytovanie a digitálne platformy.” In Míľniky práva v stredoeurópskom priestore 2019. Edited by Andrea Koroncziová, Tomáš Hlinka. 228–237. Bratislava: Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave, Právnická fakulta.

Nykiel, Włodzimierz. Ziemowit Kukulski. 2017. “Raport generalny – Transformacja systemów podatkowych w państwach Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej – 25 lat doświadczeń oraz wyzwania na przyszłość – cz. II.” Kwartalnik Prawa Podatkowego 3: 9–37. https://doi.org/10.18778/1509-877X.03.01

Pahl, Bogumił. Mariusz Popławski. Michal Radvan. Anna Vartašová. 2024. “Legal construction and legislative issues concerning the tourist tax. Comparative law case study.” Białostockie Studia Prawnicze 29(1): 113–128. https://doi.org/10.15290/bsp.2024.29.01.07

Parakala, Kumar. 2008. “We can‘t afford to fluff digital economy chance.” The Australian. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/technology/kumar-parakala/news-story/01f18696bb827224d759de60a7875d27 (accessed: 10.11.2018).

Popovič, Adrián. 2019. “Digitalizácia v oblasti daňového práva a vybrané aspekty jej realizácie v Slovenskej republike.” In Vplyv moderných technológií na právo. Edited by Michaela Sangretová. 209–220. Košice: Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice.

Priateľová, Natália. 2021. “The Directive DAC7 as a tool for fair taxation in the digital field.” In IV Slovak-Czech Days of Tax Law: Taxation of Virtual Currency and Digital Services – COVID-19 and other Current Challenges for Tax Law. Edited by Miroslav Štrkolec, Anna Vartašová, Minika Stojáková, Soňa Simić. 290–304. Košice: ŠafárikPress. https://doi.org/10.33542/SCD21-0043-1-22

Račková, Elena. Lia Košalová. Radka Hečková. Lýdia Pagáčová. Maria Vargova. 2021. “§41c.” In Komentár zákona č. 582/2004 Z. z. Zákon o miestnych daniach a poplatku za komunálne odpady. December 11, 2021. https://www.epi.sk/epi-komentar/Komentar-zakona-c-582-2004-Z-z.htm?fid=19766535&znenie=2021-12-11#content (accessed: 28.05.2024).

Radvan, Michal. 2020. “New Tourist Tax as a Tool for Municipalities in the Czech Republic.” Lex Localis – Journal of Local Self-Government 18(4): 1095–1108. https://doi.org/10.4335/18.3.1095-1108(2020)

Radvan, Michal. Zdenka Kolářová. 2020. “Airbnb Taxation.” In The financial law towards challenges of the XXI century. Edited by Petr Mrkývka, Jolanta Gliniecka, Eva Tomášková, Edward Juchniewicz, Tomas Sowiński, Michal Radvan. 481–494. Brno: Masaryk university.

Rudohradská, Simona. Diana Treščáková. 2021. “Proposals for the digital markets act and digital services act – broader considerations in context of online platforms.” In EU 2021 – the future of the eu in and after the pandemic. Edited by Dunja Duić, Tunjica Petrašević. 485–500. Osijek: Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku.

Sidor, Csaba. Branislav Kršák. Ľubomír Štrba. Michal Cehlár. Samer Khouri. Michal Stričík. Jaroslav Dugas. Ján Gajdoš. Barbara Bolechová. 2019. “Can Location-Based Social Media and Online Reservation Services Tell More about Local Accommodation Industries than Open Governmental Data?” Sustainability 11(21): 5926. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215926

Simić, Soňa. 2022. “Prevádzkovateľ digitálnej platformy ako zástupca platiteľa dane za ubytovanie v kontexte rozhodovacej činnosti súdneho dvora.” Bratislavské právnické fórum (2022)22–31.

Simić Ballová, Soňa. 2023. Zdaňovanie digitálnych služieb – inciatívy, problémy a možnosti smerovania ich daňovo-právnej regulácie. Prague: Leges.

Sme.sk. 2018. “Slovensko sa medzi prvými snaží zdaniť firmy ako AirBnB či Booking.” June 30. https://ekonomika.sme.sk/c/20881357/slovensko-sa-medzi-prvymi-snazi-zdanit-firmy-ako-airbnb-ci-booking.html (accessed: 30.10.2021).

Szakács, Andrea. 2021a. “Výmena informácií v súvislosti so zdaňovaním digitálnych platforiem.” In Bratislavské právnické fórum 2021: Aktuálne výzvy pre finančné právo. Edited by Andrea Szakács, Tibor Hlinka, Magdaléna Mydliarová, Silvia Senková, Michaela Durec Kahounová. 53–59. Bratislava: Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave. https://www.flaw.uniba.sk/fileadmin/praf/Veda/Konferencie_a_podujatia/BPF/2021/Zbornik_BPF_2021_Sekcia_8_Financne_pravo.pdf

Šebesta, Matej. Timotej Braxator. Roman Láni. Simona Kopčaková. 2020. eGovernment a jeho vplyv na podnikateľský sector. Bratislava: Implementation agency of the Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs and Family of the Slovak Republic. https://www.ia.gov.sk/data/files/np_PKSD/Analyzy/AZZZ/eGovernment_a_jeho_vplyv_na_podnikatelsky_sektor.pdf

Štrkolec, Miroslav. 2023. “Tax Law in Slovakia under the Influence of Pandemic, Digital Transformation and Inflation.” Public Governance, Administration and Finances Law Review 8(1): 91–103. https://doi.org/10.53116/pgaflr.6496

Štrkolec, Miroslav. Ladislav Hrabčák. 2022. “Tax Fairness in the Context of the Digital (Industrial) Revolution 4.0.” Studia Iuridica Lublinensia 31(4): 155–174. http://dx.doi.org/10.17951/sil.2022.31.4.155-174

Vartašová, Anna. Karolína Červená. 2023. “Digitálne platformy v segmente krátkodobého ubytovania na Slovensku – prehľad literatúry.” In 5. slovensko-české dni daňového práva: daňové právo a nové javy v ekonomike=5. Slovak-Czech days of tax law. Edited by Miroslav Štrkolec, Filip Baláži, Natália Priateľová, Anna Vartašová. 275–286. Košice: Vydavateľstvo ŠafárikPress UPJŠ. https://doi.org/10.33542/VSCD-0269-5-20

Vartašová, Anna. Diana Treščáková. 2025. “Legal basis of e-government Slovakia.” In E-Government in the Visegrad countries. Lex Localis [in print].

Vartašová, Anna. Karolína Červená. Cecília Olexová. 2022. “Taxation of Accommodation Services Provided in the Framework of the Collaborative Economy in the Slovak Republic.” Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Tourism Research 15(1): 433–440. https://doi.org/10.34190/ictr.15.1.108

FOOTNOTES

- 1 The research presented in this paper was supported by the Research and Development Agency under contract No. APVV-19-0124 “Tax law and new phenomena in the economy (digital services, shared economy, virtual currencies).”

- 2 Own calculation based on data from the Ministry of Finance of the Slovak Republic and the City of Bratislava.

- 3 These include literally everything, from typical facilities like hotels and guesthouses, through bungalows and campsites to family houses and apartments in apartment/family houses, or any other establishments providing paid temporary accommodation to a natural person.

- 4 Or, eventually, the owner of the property if the provider cannot be identified.

- 5 In the case of a so-called non-contracting state for tax purposes.

- 6 Art 8(7) of the Act No. 222/2004 Coll. on value added tax as amended.

- 7 “If an agreement is reached between the municipality and the tax remitter’s representative, and at the same time the duties of the tax remitter’s representative are established in the agreement, a special regime for tax collection for accommodation will be applied.” (Financial Directorate of SR 2023).