https://orcid.org/0009-0002-5389-8638

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-5389-8638

Abstract. Article 82 of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions requires competent legal advisors to be available, when necessary, to advise military commanders at the appropriate level on the application of International Humanitarian Law (IHL). One of the most important fields of IHL application which requires legal advice is attacks on the enemy, which need to follow the principles of military necessity, humanity, distinction, and proportionality, and are also affected by the requirement to undertake all feasible precautions in order to avoid or at least minimise incidental harm to civilians (collateral damage). One of the ways to ensure that attacks on enemy remain compliant with the requirements of IHL is by adopting appropriate targeting procedures and tools facilitating avoidance or minimising collateral damage, such as the Collateral Damage Estimation Methodology (CDEM). Media coverage of the Russian-Ukrainian war has contributed significantly to the misperception of IHL provisions applicable to targeting. During the war in Ukraine, political declarations were made several times that a war crime had occurred in the form of a deliberate attack on the civilian object. However, the legality of a particular strike can rarely be judged based upon the results of the strike or via post-strike Battle Damage Assessment (BDA). The so-called Rendulic rule emphasises that military necessity, proportionality, and precautions are judged a priori, based upon by the information available at the time of the decision (circumstances ruling at the time) and not on the basis of information emerging after the decision had been made. Legal Advirsors’ role in the targeting process requires them to possess at least the basic knowledge of the Targeting Process and the CDEM, general military expertise in the fields of Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs), as well as effects of the employment of particular weapon systems in given circumstances. This should be supported by thorough knowledge of IHL, in particular the practical aspects of its application in military operations. It should be about the intersection of legal and technical expertise.

Keywords: International Humanitarian Law, attacks, targeting, incidental harm (collateral damage), Rendulic rule

Streszczenie. Artykuł 82 Protokołu dodatkowego I do Konwencji genewskich wymaga, aby w razie potrzeby byli dostępni kompetentni doradcy prawni, którzy mogliby doradzać dowódcom wojskowym odpowiedniego szczebla w sprawie stosowania międzynarodowego prawa humanitarnego konfliktów zbrojnych (MPHKZ). Jednym z najważniejszych obszarów stosowania MPHKZ, który wymaga doradztwa prawnego, są ataki na przeciwnika, które muszą być prowadzone zgodnie z zasadami konieczności wojskowej, humanitaryzmu, rozróżnienia i proporcjonalności, a także podlegają wymogowi podjęcia wszelkich możliwych środków ostrożności w celu uniknięcia lub przynajmniej zminimalizowania niezamierzonych szkód dla ludności cywilnej (strat pobocznych). Jednym ze sposobów zapewnienia zgodności ataków z wymogami MPHKZ jest przyjęcie odpowiednich procedur targetingu i narzędzi ułatwiających uniknięcie lub minimalizowanie szkód ubocznych, takich jak Metodologia oceny strat pobocznych (Collateral Damage Estimation Methodology – CDEM). Relacje medialne na temat wojny rosyjsko-ukraińskiej znacząco przyczyniły się do błędnego postrzegania norm MPHKZ mających zastosowanie do targetingu. W czasie wojny na Ukrainie kilkakrotnie padały deklaracje polityczne, że doszło do zbrodni wojennej w formie umyślnego ataku na obiekt cywilny, jednak legalność konkretnego uderzenia rzadko można ocenić na podstawie jego rezultatów lub tzw, oceny skutków uderzenia (Battle Damage Assessment – BDA) post factum. Tak zwana zasada Rendulica podkreśla, że konieczność wojskowa, proporcjonalność i środki ostrożności są oceniane a priori na podstawie informacji dostępnych w momencie podejmowania decyzji (okoliczności danej chwili), a nie na podstawie informacji pojawiających się po podjęciu decyzji. Rola doradców prawnych w procesie targetingu wymaga od nich posiadania co najmniej podstawowej wiedzy na temat procesu targetingu i CDEM, ogólnej wiedzy wojskowej w zakresie taktyki, technik i procedur (TTP), a także skutków użycia poszczególnych systemów uzbrojenia w danych okolicznościach. Powinno to być poparte dogłębną znajomością MPHKZ, w szczególności praktycznych aspektów jego stosowania w operacjach wojskowych. Powinno nastąpić skrzyżowanie wiedzy prawnej i technicznej.

Słowa kluczowe: Międzynarodowe prawo humanitarne konfliktów Zbrojnych, ataki, targeting, niezamierzone szkody (straty poboczne), zasada Rendulica

Article 82 of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions requires competent legal advisors to be available, when necessary, to advise military commanders at the appropriate level on the application of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and on the appropriate instruction to be given to the armed forces on this subject. One of the most important fields of IHL application which requires legal advice is attacks on the enemy, defined by Art. 49 of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions (hereafter – AP I) as any acts of violence against the enemy, whether in offence or defence.

This paper shall analyse the intersection of legal and technical expertise in the targeting process, based upon the NATO doctrine, i.e. the Allied Joint Publication 3.9 (AJP-3.9) – Allied Joint Doctrine for Targeting (NATO 2021), and the practice during the Russian-Ukrainian war (NATO AJP 3.9. 2021). First, it will introduce the basic notions and concepts related to the NATO Joint Targeting Process, followed by the analysis of basic IHL principles on the targeting process, through the introduction of to the so-called Collateral Damage Estimation Methodology (CDEM), to conclude with the role of legal advisors (LEGADs) in the targeting process and summarise certain practical observations from the Russian-Ukrainian war, which began with evident Russian Aggression on 24th February, 2022.

The reason for using the NATO Targeting Doctrine as reference is simple: it is unclassified and publically-available, as opposed to the Russian or the Ukrainian targeting doctrine (however, it can be assumed that Ukraine adopted either NATO or US targeting doctrine). An analysis of the NATO targeting doctrine may aid in answering a number of important questions, including how specific targets are being selected and prioritised for engagement as well as how IHL is (or should be) affecting the targeting process.

In simple terms, targeting is the process of selecting and prioritising targets as well as appropriate means of affecting them in order to achieve a desired effect. Targeting is not only about kinetic actions (bombardment, shelling, etc.) and “putting warheads on foreheads.” It also includes non-kinetic actions, generating non-physical effects, in the cognitive and virtual domains, for example through information or psychological operations.

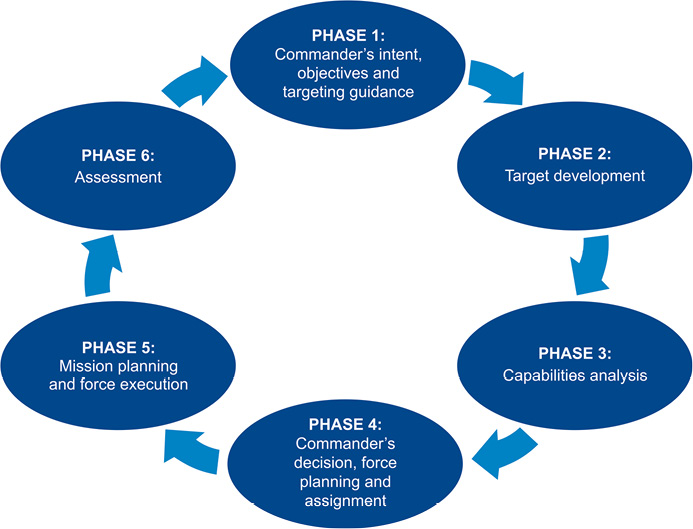

From the NATO doctrinal standpoint, a target can be anything within the “Five-O” construct: a Facility, an Individual, a Virtual entity, Equipment, and an Organisation. While the US Doctrine (JP-3.60) (United States Air Force 2021) considers as targets only such entities which belong to the enemy or support the enemy’s military effort thus constituting a threat to own forces, the NATO Doctrine does consider “friendly” entities as targets, but only for information operations, strategic communications (STRATCOM), or influencing. Therefore, the term “target” in the NATO doctrine is not a legal term of art referring to a lawful military objective, but a broader notion with operational and doctrinal meaning.

NATO defines a target as any area, structure, facility, person, or a group of people against which lethal or non-lethal means may be used to produce specific psychological, cognitive, or physical effects (including thinking, thought processes, attitudes, and behaviours) (NATO AJP 3.9. 2021, LEX-17). In NATO’s doctrinal approach, the term “target” will also include the attitudes and thought processes of civilians, including the populations of allied countries, although only information operations or strategic communication activities may be used in relation to them. It was not only the US that had raised objections to this definition, as it also deviates from the legal definition of a military objective (lawful target), provided for in Art. 52(2) of AP I: “(…) objects which by their nature, location, purpose or use make an effective contribution to military action and whose total or partial destruction, capture or neutralisation, in the circumstances ruling at the time, offers a definite military advantage.”

Notably, the US position also recognises as lawful targets those objects/entities that support the so-called war-sustaining effort,[1] i.e. “economic targets”, and in the Russian-Ukrainian war numerous examples of similar extended interpretation of military objectives have been observed by targeting decisions made by both parties (e.g. oil refineries, oil rigs, grain storage facilities, digital public services providers, banking systems).

However, other US publications quote the AP I definition of military objectives as the one the United States subscribes to as contained in Additional Protocols to the Certain Conventional Weapons Convention ratified by the USA (Smith 2020, 68).

Targeting is a comprehensive process that determines what direct and indirect, reasonably predictable effects on the target can be expected. It includes reviewing all types of objectives both separately and as part of a system and determining the actions that need to be taken to achieve operational objectives. A ‘full spectrum’ approach is used to achieve a consistent range of options and outcomes which aims to optimise military operations by avoiding duplication of effort, countervailing effects and ensuring that the right objectives are ‘engaged’ in the right order and at the right time with appropriate means.

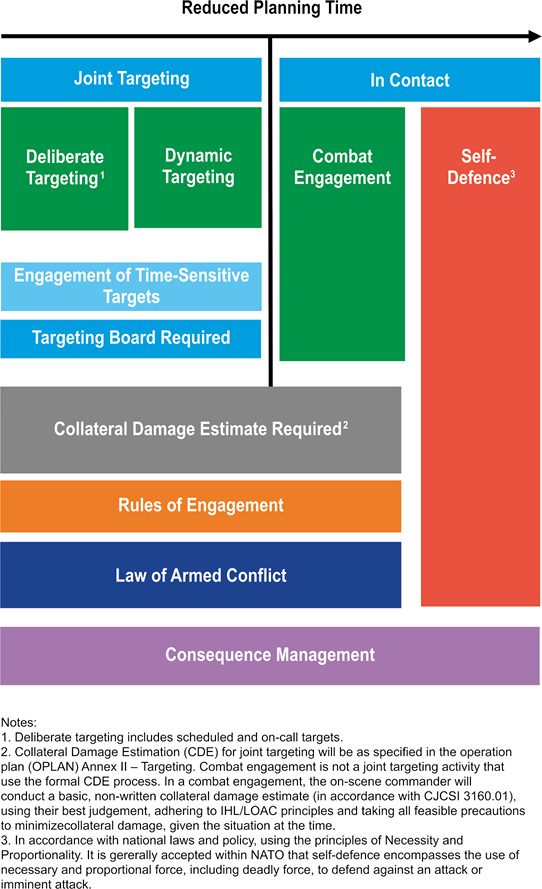

Effects on targets can be delivered in various ways: planned (deliberate), dynamically, during fire contact (combat engagement aka Troops in Contact – TIC), or in self-defence. While AP-3.9 repeatedly emphasises that targeting activities must remain within the limits of the law, including IHL, it does – in the author’s opinion – erroneously “exclude” self-defence actions from the scope regulated by IHL, which has become the subject of reservations on the part of some member states.

Planned (deliberate) targeting is carried out in relation to verified targets that are known to exist and that are to be “engaged” according to a schedule or on order. The planning of the process means that targets are appropriately verified, validated, and placed on the Joint Target List (JTL) or the Restricted Target List (RTL). Planned targeting typically supports an operational command’s future operations and future plans (NATO AJP 3.9 2021, 1–12).

Planned targeting also identifies Time-Sensitive Targets (TSTs) that are to be acted upon at a specific time or that are “on call” targets, with planned actions but not a specific action time because, for example, the time of action or their location are not yet known. In such a case, actions against these targets are planned in accordance with planned targeting procedures, but usually executed under dynamic targeting procedures.

Dynamic targeting applies to targets that, due to the dynamic operational situation, pose (or will soon pose) a threat to own (allied) forces or to the mission, and whose elimination supports the achievement of the commander’s objectives at a given time. Those could be already verified targets from the JTL/RTL that were not indicated for action in the planned targeting process, targets that are being developed (information necessary to service these targets is still being collected on them), or unforeseen targets and, therefore, not included in the JTL/RTL.

Dynamic targets are typically known to be in the area of operations, have been partially developed, but have not been detected, located, or selected for action in time sufficient for them to become planned targets. Dynamic targeting also applies to unexpected targets that meet the criteria specified in the operational level assumptions. In such cases, additional resources are required to complete target development, validation, and prioritisation.

It may be possible to prosecute dynamic targets by redirecting existing resources in line with the operational commander’s intentions and targeting guidelines, as they typically require faster action than planned targets (NATO AJP 3.9 2021, 1–13)

Time-sensitive targets (TSTs) can be serviced in both planned and dynamic modes, depending on the time available. TSTs are prioritised, categorised, and coordinated at the operational and tactical levels. The authority to take action against a TST (the so-called Target Engagement Authority – TEA) is specified in Annex II to the operations plan (OPLAN).

Action against a TST may require accepting a higher level of risk to successfully engage the TST while simultaneously committing the resources of various (sometimes all) components (land, air, maritime, cyber) to detect, locate the target, and evaluate the results of target engagement. In particular, this applies to the Joint ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance Reconnaissance) resources at the operational level, which provide access to data in almost real time to effectively carry out the TST procedure. And, indeed, intelligence is a driving factor for the whole targeting process.

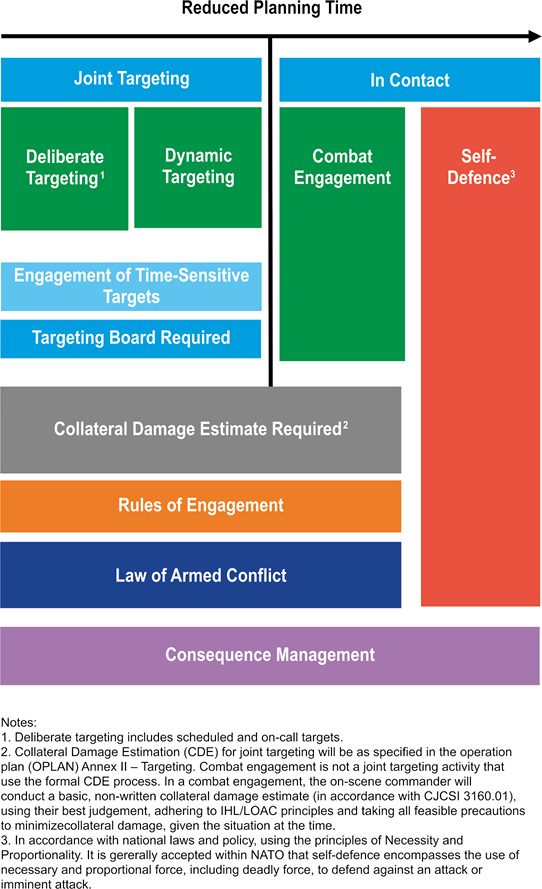

The joint targeting cycle is inextricably linked to the JISR process, and intelligence information (INTEL) is necessary not only to detect the target, but also to determine its nature, role, importance for the enemy, and, therefore, the priority assigned by the operational level commander. The cycle is run in six phases.

The Joint Targeting Cycle, AJP-3.9, p. 1–14

From the perspective of a LEGAD, Phase 2 (Target Development) is the most critical one. It is during this phase that targets are identified and selected for specific engagement and verification whether such engagement would be lawful. The second phase involves the validation of the target, which consists in ensuring compliance with the law (including IHL) and Rules of Engagement (ROE),[2] higher-level political and military guidelines, and the commander’s intent. Target validation requires verifying the accuracy, credibility, and reliability of the intelligence (INTEL) data based on which the target was developed, and then cross-referencing it with legal analysis against criteria for the definition of a permissible military target and compliance with mandate/other policy guidelines (NATO AJP 3.9. 2021, 15–16).

Target development is based on a system analysis, supported by the so-called JIPOE (Joint Intelligence Preparation of the Operation Environment), which enables the assessment of the contribution of individual targets to the operational capabilities of the enemy.

Target development relationships, AJP-3.9, p. 1–17

The purpose of target validation is to ensure the lawfulness of both the target and selected means or methods of engaging it. As previously mentioned, NATO’s doctrinal definition of a target is broader than a lawful military objective. Joint targeting must be consistent with the applicable legal framework – in particular the four core IHL principles of humanity, military necessity, distinction, and proportionality – and take into account the requirement to take feasible precautions in attack, as embodied in IHL. AJP-3.9 recognises that in armed conflicts the use of the term “target” does not imply that they may be lawfully engaged under IHL (see, e.g., “friendly” actors which may only be subject to information/influence or STRATCOM activities). A legal assessment must be carried out before any engagement. Similarly, in situations other than armed conflict, a legal assessment before any targeted action is taken must be conducted on the basis of the applicable legal framework, including the principle of proportionality under international law (NATO AJP 3.9. 2021, 1–4).

If legality is one of the cornerstones of the targeting process, the four core principles of IHL will have a significant impact on the process. There is no intent to repeat the meaning of the principles in this paper but, rather, to “translate” them into the language of the targeting process.

HUMANITY. This principle means the prohibition to cause superfluous injuries of unnecessary suffering to enemy combatants. It stems from the customary IHL norm that the right to choose means and methods of warfare is not unlimited. This is sometimes referred to as the principle of limitation, which is reflected in a series of treaty-based rules restricting specific means and methods of warfare. In the law of armed conflict, means and methods of warfare include weapons in the widest sense as well as the way in which they are used. Therefore, the law of armed conflict limits both the types of weapons that may be used and the manner in which they may be used. It is prohibited to use a weapon that by its very nature causes superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering to combatants, or to use any weapon in a manner that causes superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering. In the targeting process, it mainly affects the selection of appropriate means of engaging targets (in targeting jargon referred to as “weaponeering”), as to avoid weapons either prohibited by IHL (e.g. expanding bullets, undetectable fragments, poisonous weapons or poisoned projectiles, chemical weapons, biological weapons, etc.) or prohibited use of otherwise lawful weapons (NATO AJP 3.9. 2021, 1–8, para 0120.a). By reference to the war in Ukraine, this does not include incendiary weapons, which are not prohibited per se, although their use against personnel raises doubts with regard to the unnecessary suffering or superfluous injuries. Additional Protocol 3 to the CCW prohibits the use of air-delivered incendiary weapons in the vicinity of the concentrations of civilians, but does not outlaw incendiary weapons as such. It also does not regulate the use of smoke rounds (e.g. white phosphorus), illumination rounds, or the so-called “combined-effects munitions”, e.g. thermobaric or High Explosive/Fragmentation/incendiary such as the infamous Russian OFZAB-500 (Осколочно-фугасно-зажигательная авиационная бомба – Fragmentation-Blast-Incendiary Aviation Bomb) aviation bomb (Rosoboronexport. N.d.), often erroneously reported as being prohibited by IHL (NATO AJP 3.9. 2021, 1–18).

The most often used incendiary weapon in the Russian-Ukrainian war was 9M22S (Missilery n.d.; Collective n.d.) incendiary cluster munitions for BM-21 Grad Systems, used by both parties (Ukraine and Russia), containing thermite type incendiary substance. Since these are rocket artillery rounds, they do not fall under the prohibition to use air-delivered incendiary bombs in the vicinity of concentration of civilians.

MILITARY NECESSITY. This principle allows the use of force not otherwise prohibited by IHL that is necessary for the partial or complete submission of the enemy. Military necessity is not an overriding principle allowing breaches of IHL (NATO AJP 3.9. 2021, 1–8). In the targeting process, military necessity is closely related to humanity and weaponeering. It may be translated into using the minimum force or a weapon with minimum damage potential necessary to achieve the desired effect on the target.

PROPORTIONALITY. An attack is prohibited when it may be expected to cause incidental harm to civilians and civilian objects consisting of incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, damage to civilian objects, or a combination thereof which would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated. Military advantage and incidental harm to civilians and civilian objects are two very dissimilar concepts, and it is, therefore, difficult to strike a balance between them as the law requires. There is no mathematical formula that will decide whether the destruction of a particular military objective warrants the reasonably foreseen death or, other, harm to a certain number of civilians or civilian objects of a particular type. Nevertheless, the law requires both officers and soldiers to make such a good faith assessment, based on all information reasonably available to them (Rendulic rule), and to decide whether a proposed attack crosses the threshold of expected “excessive” incidental harm (NATO AJP 3.9. 2021, 1–9). It must be stressed that proportionality assessment is conducted ex ante or ante factum and – as it will be discussed in the final part of this paper – assessment based upon the results of a strike (post factum) is usually not conclusive in determining whether the principle of proportionality was observed.

DISTINCTION. The principle of distinction imposes an obligation on all targeting decision-makers to distinguish between legitimate targets and civilian objects and the civilian population. The rule that requires only the targeting of military objectives is an expression of this principle.

Only targets that are military objectives may be attacked. Certain installations/facilities/objects that have both military and civilian uses (referred to as “dual-use” facilities) are more difficult to identify as lawful legitimate military objectives. Examples of possible dual-use facilities include bridges, electrical systems, fuel, communication nodes, vaccine, and chemical plants, etc. Before attack, these dual-use facilities must be carefully analysed based upon the current situation and information to determine if they are legitimate military objectives (NATO AJP 3.9. 2021, 1–8).

Indiscriminate attacks are prohibited. Accordingly, any attack must be directed at a specific lawful military target, must employ means and methods of combat which are capable of being directed at a specific lawful military target, must employ means and methods of combat the effects of which can be limited as required by the law of armed conflict; and if the proposed attack is aimed at clearly separated and distinct military objectives in an area containing a concentration of civilians or civilian objects, it must be conducted as separate attacks on each military objective.

Distinction is the principles requiring adequate, accurate, credible, and reliable INTEL, facilitating the target validation, but also proportionality assessment and precautions in attack (NATO AJP 3.9. 2021, 1–18).

PRECAUTIONS IN ATTACK. While not necessarily universally considered as a core principle of IHL by all NATO member states, precautions in attack are universally recognised as a requirement of customary IHL, even by states not parties to Additional Protocol 1. AJP 3.9 does reflect the requirement to undertake all feasible precautions *as part of legal review prior to engagement (NATO AJP 3.9. 2021, 1–4), under the proviso that “(t)he word ‘feasible’ in this context means what is practicable, or practically possible, considering all the circumstances at the time using all the information reasonably available. Some nations refer to ‘feasible precautions’, vice ‘all feasible precautions’” (NATO AJP 3.9. 2021, 1–18). Two more phases in the NATO-approved targeting cycle, which require LEGAD’s inputs, advice, and oversight will thus be Phase 4 – where the servicing agency (the component delivering the effect on target) is selected, alongside with the ‘weaponeering solution’ i.e. the selection of means and methods necessary to achieve the deliver the desired effect on the target – and Phase 5, where the actual engagement takes place and based upon the circumstances ruling at the time may require either a change of the selected delivery method or even an abortion of the engagement, should it be expected that expected incidental losses are excessive compared to anticipated military advantage.

While in 20 years of NATO’s focus on counterinsurgency (COIN) operations, with technological supremacy over the adversaries and total air dominance, the policy (not a legal standard, though) requirement of zero CIVCAS (civilian casualties) was – at least theoretically – achievable and enforceable, in high-intensity urban warfare it would be unreasonable to expect, as recently demonstrated by the Russian-Ukrainian war and Israeli operations in the Gaza Strip triggered by Hamas’s terrorist attack on 7th October, 2023. Nevertheless, precautions in attack still are a valid requirement, and the NATO’s targeting doctrine does take that into account. One of the possible methods of undertaking feasible precautions is the application of the so-called Collateral Damage Estimation Methodology (CDEM).

The Collateral Damage Estimation (CDE) is a product of the process of the “Joint Methodology for Estimating Collateral Damage and Casualties for Conventional Weapons: Precision, Unguided, and Cluster”.[3] This part will be based upon the author’s experience and observations from the practical application of the CDE Methodology in NATO’s targeting process, in line with the aforementioned “Joint Methodology…”

What is the Collateral Damage Estimation Methodology (CDEM)? It is a balance of science and art that produces the best judgment of potential damage to collateral concerns. The CDEM encompasses the joint standards, methods, techniques, and processes for a commander to conduct the CDE and mitigate unintended or incidental damage or injury to civilian or non-combatant persons or property or the environment. The CDEM assists commanders in weighing risk against military necessity and in assessing proportionality within the framework of the military decision-making process, and is a means for assisting a commander in adhering to LOAC, in particular precautions in attack and – if the threshold of Casualty Estimate (CE) within CDE Level 5 (to be explained below) is reached – proportionality assessment.

The CDEM technical data and processes of the methodology are derived from physics-based computer models, weapons test data, and operational combat observations. All contain some degree of inherent error and uncertainty. The CDEM is not itself a decision – it only informs a commander’s decision and its application relies on sound judgement. The CDEM is not the only input to a commander’s decision-making in the targeting process. There will be other factors to be taken into account: LOAC, the Rules of Engagement (ROE), target characteristics (inter alia nature, function, purpose or use), operational objectives, political guidance, STRATCOM considerations, etc.

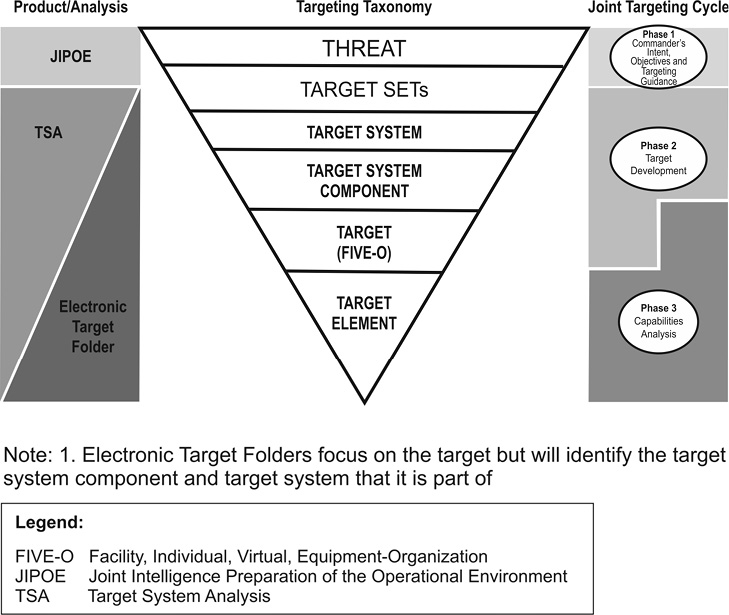

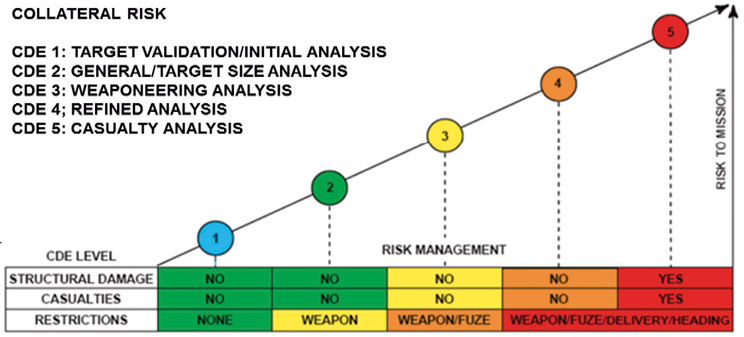

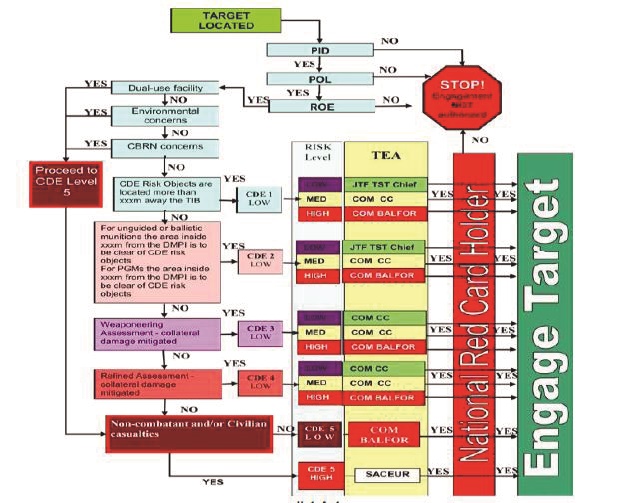

It is based on five mutually-dependent CDE levels (CDE Level 1 through Level 5), each level being based on a progressively refined analysis of available intelligence, weapon types and effects, physical environment, target characteristics, and delivery method. For each of the levels, a simple YES/NO test is to be conducted for three aspects, which the diagram below explains.

Five steps of progressive CDE assessment, CJCSI 3160.01, p. D-A-3

If the answer to any of the three questions is ‘YES’, it requires a mandatory move to the next CDE level and the conduct of the same three-question test until receiving three ‘Nos’ or reaching CDE Level 5, where despite all the precautions or mitigation measures, damage to CIV objects or non-combatant casualties is inevitable and there is a need to estimate the casualties.

The CDEM is thus a valuable tool in employing precautions in attack (e.g. by selecting the ordnance to be used, fusing, delivery method, direction and tactics), thus making it possible to either mitigate the expected collateral damage (incidental losses) or assess the extent of expected collateral damage when mitigation is not possible.

It is not the LEGAD’s role to assess the CDE level – it is responsibility of the targeting cell. The LEGADs do need to know what the implications are, including the respective Target Engagement Authority (TEA).

An example of a Target Engagement Authority (TEA) Matrix

Also, sometimes LEGADs need to ask the right questions, in particular in areas which the CDE Methodology does not account for. One of the examples refers to secondary effects. They need to be taken into consideration when there is the risk of the occurrence of such effects, in particular when they have the potential to outweigh the primary effects of the ordnance. A proportionality analysis needs to take into account all the factors which are foreseeable when conducting the analysis with due diligence. IHL requires both officers and soldiers to make such a good faith assessment based on all information reasonably available to them, and to decide whether a proposed attack crosses the threshold of expected “excessive” incidental harm.

This requirement is reflected in the so-called Rendulic rule, which was formulated by the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg in the so-called “Hostage Case”.[4] Under the Rendulic rule, acts of soldiers and commanders on the battlefield should be assessed by the information available to them at the time of the decision (Smith 2020, 58; Sliedregt 2003, 125–126, 304, 314) (circumstances ruling at the time) and not on the basis of information emerging after the decision had been made. The rule establishes the standard of a reasonable commander, which requires that decisions made by the commander are judged based upon information obtained or possible to obtain when exercising due diligence (Piątkowski 2013, 69, 74, 76–77).

The CDEM does not always predict the actual outcome of weapon employment. Intelligence fidelity and timeliness, operational considerations, weapon reliability, or delivery method alterations are some reasons for differences. However, the CDEM enables a reasonable determination of collateral damage inherent in weapons employment, thus addressing IHL requirements for reasonable precautions to minimise effects of combat on the civilians/civilian population or non-combatants.

CDM does not account for weapon malfunction, operational delivery errors, or altered delivery tactics based on aircrew judgment. It cannot “predict” or model unknown transient civilian or non-combatant personnel and/or property (e.g. vehicles or pedestrians) in the target area. Most importantly, CDE does not account for secondary effects (e.g. ammo cook-off); therefore, it does not replace all means of proportionality assessment.

While the CDEM offers a tool for modelling and assessing the expected incidental losses as well as possible mitigation measures, thus constituting one of the feasible precautions, it should be noted that the formal CDE process, with the complete employment of the CDEM, is time-consuming and in given circumstances may not be feasible (time constraints, dynamic engagements, an inability of the software and certified operators). It could then be substituted with the so-called “field CDE”, understood as the best assessment of expected incidental losses based upon the experience and expertise of the personnel conducting it.

Also, the CDEM does not replace proportionality assessment, as it only provides the first half of the proportionality analysis, i.e. the expected incidental losses, but not the anticipated military advantage, which needs to be assessed separately and may produce results significantly affecting the balance between incidental losses (humanity) and military advantage (military necessity). Maintaining this balance is the primary purpose of IHL.

Therefore, relying solely on the CDEM for the proportionality assessment or utilising the CDEM as the only precautionary measure would probably not satisfy the reasonable commander standard, which – as per the Rendulic rule – should apply not only to assessing military necessity, but also proportionality and precautions (Hayashi 2023). As stated above, the application of the CDEM does not relieve the personnel involved in target nomination and prosecution (including commanders) from the requirement to actively seek highest possible intelligence fidelity. However, intelligence itself is not enough to remove the probability of errors resulting from negligence, duress, or poor judgement of subordinates, but commanders’ errors may be culpable if they are not “(…) subjectively honest and objectively reasonable” (Hayashi 2023). In “the circumstances ruling at the time”, the requirement for feasible precautions may actually mean the necessity of going above and beyond what the CDEM can provide (produce) and employing other mitigation measures, such as additional INTEL, environmental, Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear (CBRN) or engineering assessments, the employment of Precision-Guidance Munitions (PGMs), etc.

Legal advisors bear a significant responsibility in the targeting process. LEGADs are one of the three core participants in the Joint Targeting Cycle explicitly mentioned in the NATO’s Targeting Doctrine, ensuring a legal assessment of the targets and desired effects, supporting the development of collateral damage prevention procedures based on commanders’ guidance and higher-level directives and ensuring that targeting efforts are aligned with the legal framework and that IHL principles are integrated along the whole process from target discovery through validation and engagement (NATO AJP 3.9. 2021, 1–23). While targeting procedures may be more restrictive than permitted by IHL, they may never be more permissive. Commanders should receive training in IHL and have the LEGAD’s support available when needed. This legal support should include as a minimum target validation in Phase 2 of the Joint Targeting Cycle (determining that the criteria of lawful military objective are met), i.e. satisfying the requirements of distinction, force planning and assignment in Phase 4 (in particular the selection of means and methods – weaponeering) addressing military necessity and humanity and target engagement in Phase 5 (including the CDEM and recommendation to abort engagement in case of expected excessive incidental losses), thus following the requirements of proportionality and precautions in attack.

This requires the LEGADs to possess at least the basic knowledge of the Targeting Process and the CDEM as well as general military expertise in the fields of Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) as well as effects of the employment particular weapon systems in given circumstances. This should be supported by thorough knowledge of IHL, in particular the practical aspects of its application in military operations.

The media coverage of the Russian-Ukrainian war has contributed significantly to the misperception of IHL provisions applicable to targeting: from erroneous statements regarding the use of incendiary weapons, to “sentences” or “verdicts” issued by the media classifying certain incidents as war crimes despite the lack of basic knowledge of the principles of IHL.

During the war in Ukraine, political declarations were made several times that a war crime had occurred in the form of a deliberate attack on civilian objects. For example, at the beginning of the war, the “Retroville” shopping mall near Kiev was struck, which, as open sources later revealed, was used to shelter Ukrainian BM-21 launchers. The second example is the strike on the “Amstor” shopping mall in Kremenchuk, considered by Ukrainian authorities as a deliberate attack (if so, it would constitute a war crime). However, the hit on the shopping centre was most likely the result of the lack of precision of the Kh-22 missiles used to attack the Road Machinery Plant. KREDMASH, which constituted a lawful military objective as a dual-use facility. In this case, we can talk about the Russians’ failure to take precautions in attack in the sense of the selection of means of warfare (weaponeering), and, therefore, a violation of Article 57 AP I, which, however, does not constitute a war crime (Bellingcat 2022).

After more than 20 years of NATO’s involvement in peace enforcement or stability operations of counterinsurgency (COIN) type, with total air dominance and significant technological supremacy over the adversaries, public opinion has got used to “zero CIVCAS” being an actual legal requirement. The Russian-Ukrainian war is an evident example that this standard is impossible to sustain in high-intensity urban warfare. Nevertheless, media often portray every case of a civilian casualty as a violation of IGL or even a war crime, mainly based upon ex ante/ante factum analyses.

The legality of a particular strike can rarely be judged based upon the results of the strike or via post-strike Battle Damage Assessment (BDA). The presence of civilians or the occurrence of civilian casualties does not determine the civilian character of the object, just as it cannot shield a military objectives from attack. A dual-use facility is a lawful military objective, although its dual use will complicate the proportionality assessment.

Trying to verify the correctness of proportionality assessment by means of post-strike BDA is a fundamental mistake. Proportionality assessment is conducted ahead of the strike, not afterwards. Actual casualty numbers do not necessary matter in assessing proportionality. IHL does not prohibit/outlaw inflicting incidental losses (including CIV casualties). IGL prohibits attacks, which are expected to cause excessive incidental losses compared to definite military advantage anticipated as a result of the strike. This professional judgement should be based upon INTEL and tools available for the assessment of the result of the strike during its planning.

Not all ordnance impacts on civilian objects are results of deliberate targeting (war crimes). There are so many variables in the equation that without in-depth knowledge of the decision-making process behind each strike, including INTEL used in support of such decision, making conclusive assessments is virtually impossible. Not to mention technical factors, such as weapons malfunctions, failure of guidance systems, enemy’s counteractions (air defence, electronic countermeasures, jamming, etc), or deviations from established delivery method and tactics.

While certain factors, e.g. the use of precision-guided munitions, may be an indicator of the intent to strike a particular object, jamming or other forms of electronic countermeasures may have a significant impact on the accuracy of a weapon system. Without access to background INTEL, it is impossible to assess what level of knowledge a particular commander authorising the strike had at the moment when the strike was authorised (circumstances ruling at the time).

While certain objects, e.g. critical infrastructure facilities – especially electrical grid and electricity production facilities – are particularly controversial targets, in most of the cases they constitute dual-use objects and thus lawful military objectives in accordance with state practice, dating back to the operation Desert Storm. As stated by the US Department of Defence, “[e]lectricity is vital to the functioning of a modern military and industrial power such as Iraq, and disrupting the electrical supply can make destruction of other facilities unnecessary. Disrupting the electricity supply to key Iraqi facilities degraded a wide variety of crucial capabilities, from the radar sites that warned of Coalition air strikes, to the refrigeration used to preserve biological weapons (BW), to nuclear weapons production facilities” (Department 1992, 127).

The impact of the strikes on Ukrainian electricity infrastructure and on civilian populace has been tremendous. However, without the access to Russian INTEL and other data stored in Russian targeting support systems, assessing whether the anticipated military advantage from disabling the energy infrastructure justified the impact on the civilian populace is extremely difficult. Nonetheless, taking into account that the strikes on this infrastructure took place mostly in cold autumn and winter periods, it can be reasonably assumed that their main purpose was to affect, if not terrorise, the civilian populace. If this purpose is proven by independent and impartial inquiries, these attacks would constitute a violation of Art. 33 of the Geneva Convention IV as well as Art. 52(2) of AP I. Proving this intended purpose would – to a large extent – require access to Russian background data, which is a highly unlikely condition to be fulfilled while the current regime is in power, unwilling to cooperate with the International Community and – specifically – with the International Criminal Court.

Bellingcat Investigation Team. 2022. “Russia’s Kremenchuk Claims Versus the Evidence.” Bellingcat, June 29, 2022. https://www.bellingcat.com/news/2022/06/29/russias-kremenchuk-claims-versus-the-evidence/ (accessed: 2.11.2023).

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction (CJCSI) 31260.01. 2009. No-Strike and the Collateral Damage Estimation Methodology.

Collective Awareness to UXO. N.d. “9N510 (ML-5) Submunition”, https://cat-uxo.com/explosive-hazards/submunitions/9n510-ml-5-submunition (accessed: 31.10.2023).

Department of Defense. 1992. “Conduct of the Persian Gulf War, Final Report to Congress” Washington, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA249270.pdf (accessed: 2.11.2023).

Department of the Navy. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations and Headquarters. US Marine Corps. Department of Homeland Security. US Coast Guard. 2007. The Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations, NWP 1–14M/MCWP 5–12.1/COMDTPUB P5800.7.

Hayashi, Nobuo. 2023. “Honest Errors, The Rendulic Rule and Modern Combat Decision-Making.” Lieber Institute West Point Articles of War, October 24, 2023. https://lieber.westpoint.edu/honest-errors-rendulic-rule-modern-combat-decision-making/

Missilery. N.d. “Unguided rocket projectile MZ-21 (9M22S)”, Missilery.info, https://en.missilery.info/missile/grad/m3–21 (accessed: 31.10.2023).

PAP. 2022. “Media: Rosja użyła w Czernichowie zakazanych lotniczych bomb zapalających.” Polska Agencja Prasowa, March 10, 2022, https://www.pap.pl/aktualnosci/news%2C1110670%2Cmedia-rosja-uzyla-w-czernihowie-zakazanych-lotniczych-bomb-zapalajacych

Piątkowski, Mateusz. 2013. “The Rendulic Rule and the Law of Aerial Warfare.” Polish Review of International and European Law 3: 69–85. https://doi.org/10.21697/priel.2013.2.3.03

Rosoboronexport. N.d. “OFZAB-500”, http://roe.ru/eng/catalog/aerospace-systems/air-bombs/ofzab-500/ (accessed: 31.10.2023).

Sliedregt, Elies van. 2003. The Criminal Responsibility of Individuals for Violations of International Humanitarian Law. Hague: TMC Asser Press.

Smith, Micah. Ed. 2002. Operational Law Handbook. Charlottesville: The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School.

International Military Tribunal Case 7: The “Hostage Case,” US v. List et al., https://nuremberg.law.harvard.edu/nmt_7_intro#judgement

NATO. 2019. MC 0362/2, NATO Rules of Engagement, 18 July 2019.

NATO. 2021. AJP-3.9 Allied Joint Doctrine for Joint Targeting. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/618e7da28fa8f5037ffaa03f/AJP-3.9_EDB_V1_E.pdf (accessed: 30.10.2023).

Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of August 12, 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts, Adopted June 8, 1977, Entered into Force December 7, 1978.

United States Air Force. 2021. Air Force Doctrine Publication 3–60, Targeting, https://www.doctrine.af.mil/Portals/61/documents/AFDP_3–60/3–60-AFDP-TARGETING.pdf.

United States, Military Commissions Act. 2006. Public Law 109–366, Chapter 47A of Title 10 of the United States Code, October 17, 2006, p. 120 Stat. 2625, § 950v(a)(1), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-109publ366/html/PLAW-109publ366.htm (accessed: 21.10.2023)