https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6497-6529

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6497-6529

Abstract. Self-employment has traditionally been regulated by the Civil Code, as a distinctive form of work apart from employment. This chapter strives to evaluate the labour law framework and labour market experience of self-employment. First, the Hungarian legal provisions on self-employment will be highlighted, including labour law, civil law and social security law. This will be followed by an evaluation of the available data on labour market trends regarding the various groups of self-employed workers, such as genuine and false self-employment, and economically dependent work. After this summary on employment data, the legal protection or scope of employee rights enjoyed by self-employed persons will be scrutinised. Finally, I will examine the Hungarian legal mechanisms to combat false self-employment. As a whole, the paper will provide a picture of the legal environment of self-employment with laws, trends and some evident flaws. I will strive to highlight the main driving forces behind self-employment and related labour law policy.

Keywords: labour law, self-employment, employment relationship, Hungarian law, economic dependence, bogus self-employment

Streszczenie. Samozatrudnienie jako rodzaj świadczenia pracy zarobkowej odrębny od zatrudnienia jest uregulowane przede wszystkim w węgierskim kodeksie cywilnym. W niniejszym opracowaniu autor ocenia ramy prawa pracy, jak i węgierskie doświadczenia dotyczące samozatrudnienia na rynku pracy. W pierwszej kolejności dokonuje analizy węgierskich przepisów regulujących samozatrudnienie, w tym prawo pracy, prawo cywilne i prawo ubezpieczeń społecznych. Następnie autor przeprowadza ocenę dostępnych danych o tendencjach na węgierskim rynku pracy odnośnie różnych grup samozatrudnionych, ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem rzeczywistego i fikcyjnego samozatrudnienia w świetle pracy ekonomicznie zależnej. W dalszej części rozdziału autor charakteryzuje ochronę prawną osób pracujących zarobkowo na własny rachunek, wskazując na zakres uprawnień przynależnych osobom samozatrudnionym. Na koniec dokonuje analizy węgierskich mechanizmów prawnych mających na celu walkę z fikcyjnym samozatrudnieniem. W niniejszym rozdziale autor prezentuje obraz otoczenia prawnego samozatrudnienia na Węgrzech wraz z przepisami, tendencjami i oczywistymi niedociągnięciami. Stara się również podkreślić główne czynniki prowadzące do pracy na własny rachunek i powiązaną z nimi politykę w zakresie prawa pracy.

Słowa kluczowe: prawo pracy, samozatrudnienie, stosunek pracy, prawo węgierskie, zależność ekonomiczna, fikcyjne samozatrudnienie

The employment relationship is still the most important legal relationship with respect to work, however, civil law contracts, as the only alternative, have also been playing an important role in the binary model. In this first chapter, I will outline the legal framework of work relationships and the legal provisions specifically aimed at self-employed workers, including relevant rules of labour law, civil law and social security law.

The Hungarian structure of work relations may be labelled as a binary model, based on employment contracts on the one hand, and civil law contracts on the other. The typical employment relationship has always been and remains the dominant legal form of work, which is regulated by a separate law, the Labour Code of 2012 (henceforward: Labour Code).[1] Atypical forms of employment are far from being as widespread as in the western European Member States, because they still represent only a fraction of employees, particularly fixed-term employees and agency workers. Certainly, the labour law heritage of the socialist period is stronger than the effect of EU labour law harmonisation regarding atypical contracts.

Beyond employment relationships, there are exclusively civil law contracts, which provide a cheaper and far less regulated alternative contractual framework for workers. The ‘cost and benefit’ of this contractual choice will be analysed in Chapter 3 on the legal protection of self-employed persons, so at this stage I focus on the legal environment of civil law contracts. These contracts are regulated by the Civil Code as a legal relationship between two equal parties, without cogent rules and employment protection. Thus, the parties may freely govern their relationship in the contract within the loose regulatory framework provided by civil law. Civil law work contracts lack hierarchy between the parties, the personal and economic subordination of worker and principal.

The Civil Code has traditionally regulated two kinds of work contracts,[2] which are present in the current legal text as well,[3] namely ‘personal service contracts’ and ‘work contracts’. Both contractual types provide a legal framework for work performed by self-employed workers. At the same time, personal service contracts provide the more popular legal form of regular, permanent work relations, since they are based on the ‘obligation to care’: the agent undertakes to carry out the assignment the principal has entrusted to him, and the principal undertakes to pay the remuneration contracted.[4] At the same time, under a work contract, the contractor undertakes to perform activities to achieve the agreed upon result and the customer undertakes to accept delivery of and pay the contracted fees.[5] Therefore, personal work contracts are the usual form for disguising an employment relationship in several sectors, for instance in entertainment, security work, office work, construction, etc.

The third legal category of economically dependent work (in addition to employment and civil law contracts), as it is known in several European legal systems,[6] has not been regulated in Hungary. There was a theoretically inspiring proposal on this third labour law category in the first draft of the Labour Code 2011, however, without any effect on current legislation.[7] Thus, self-employment covers three rather different groups of employment arrangements: genuine self-employment, economically dependent work and bogus (false) self-employment, which all play some role in the Hungarian labour market. Genuine self-employment covers independent contracts, where the relationship between the parties is not characterised by personal or economic dependence. Economically dependent work lacks personal dependence on the employer, but shows a high level of economic dependence on one (decisive) client (quasi-employer). Bogus (false)[8] self-employment is an employment relationship with a high level of personal and economic dependence, however, the parties reduce employment-related costs (through lower public charges and fewer employer obligations) by concluding a civil law contract.

The abovementioned self-employed persons use personal service contracts but opt for either ‘individual entrepreneurship’, or membership in a business association when it comes to legal status. Membership in business associations is regulated by the Civil Code.[9] Membership in a ‘limited partnership’ is by far the most common solution in the Hungarian labour market, as it is the easiest and cheapest way to run a company (business association) for the exclusive purpose of providing personal work service. The unlimited amount of the capital contribution is the main advantage of a limited partnership, so this business association may be rapidly established with a small amount of capital,[10] in contrast to other options.

An individual entrepreneurship (individual company), in turn, is regulated by a special Act.[11] An individual entrepreneurship and individual company may be easily established and also employ other workers. These two groups (individual entrepreneurs and members of business associations) may equally use the same taxation systems to achieve a much lower cost level than within an employment relationship. I will analyse the available data on their respective numbers in Chapter 2 to determine the scale of self-employment. Before turning to these statistics, however, I will outline the various solutions for acquiring social security rights in the case of self-employment.

There is a statutory obligation to pay contributions, affecting employees, civil servants, service providers, and the self-employed working alone, or in organisations. In employment, the contributions are paid by employers (19%) and employees (18.5%) separately, but self-employed workers pay exactly the same high rates themselves (altogether 37.5%).[13] Self-employed workers automatically become ‘insured’ in the state social security system[14] if their income exceeds 30% of the minimum wage.[15]

Self-employed persons must pay the abovementioned social security contributions calculated on the basis of their income, but this is subject to a statutory minimum (’expected’) contribution. They cannot avoid the payment of a minimum contribution even if their income is lower than the basis of the calculation (or they have no income at all). The ‘expected contribution basis’, which is a kind of expected income, is the minimum wage for pension contribution and 150% of the minimum wage for health and unemployment contributions.[16] The social security rights in the general scheme will be examined in Chapter 3 on legal protection of self-employed workers.

As has been elucidated above, social security contributions are high, but potential social services are significantly lower quality than in Western Europe. Clearly, self-employed workers are not very attracted by these services and do their best to avoid paying the high social security contribution. This has been a strong incentive for undeclared work, or payment of tax through a sham company without social security contributions. Thus, legislation has been constantly providing cheaper special schemes for self-employed workers, which has been the main incentive of bogus self-employment.

In these special social security and taxation schemes, the total cost of employment (taxes + social security contributions) is much lower, but social services are also limited. This is a special ‘deal’ between the state and the individual, where workers give up publicly financed social rights (future payments, services) for higher income (through lower contributions). The two existing special schemes will be analysed below, in order to show the fragmentation of the Hungarian social security system: a) Small Taxpayer Entrepreneurs’ Lump Sum Tax (KATA) and b) Simplified Public Burden Contribution (EKHO).

The Small Taxpayer Entrepreneurs’ Lump Sum Tax (KATA)[17] is the most popular ‘alternative’ taxation form for self-employed workers, which has been providing a cheap alternative to the general taxation and social security scheme since 2013. It is available to individual entrepreneurs, individual firms, limited partnerships and unlimited liability companies with only natural person members, and law firms. Thus, self-employed workers may use it to escape high taxes and social security contributions. The worker/company only has to pay HUF 50,000 per month[18] (HUF 600,000/year, circa EUR 1,700) up to a maximum income of HUF 12 million (circa EUR 34,000) per year. This low lump sum burden includes all taxes and contributions, which must be paid by the worker (quasi-employee) and the company (quasi-employer).

Taking as an example the maximum possible income of HUF 12 million (circa EUR 34,000) in this taxation system,[19] this represents a 5% overall public charge. Moreover, the higher the income of the worker, the lower the proportion is paid to the budget through this lump sum tax. This low lump sum tax is shockingly low in comparison with the 37.5% general social security contribution (excluding tax). Consequently, this taxation form became extremely popular among the self-employed in a very short time, which will be described in Chapter 2 on the scale of self-employment.

The government realised the increasing attraction posed by the KATA tax method that drew workers from employment to self-employment. As a response, an extra 40% income tax was levied on all income over HUF 3 million from the same employer[20] from 2021, which represented a legal punishment for those disguising their employment in this way.[21] The related limited social security rights will be examined in Chapter 4 on the legal protection of self-employed workers.

Although this new (second) 40% tax rate puts an extra burden on employers using this form to hide employment through false self-employment, it also punishes employees with higher income. For instance, a self-employed worker with higher income may have 3 clients over this 3 million threshold. This case does not involve allegations of false self-employment, but the extra tax must be paid by all three clients, which considerably raises the cost of self-employment, without any effect on false self-employment. So this new tax increase has two sides and calls our attention to the importance of increasing state revenues. The state first attracted self-employed workers to this tax pool and later increased the tax burden to earn a higher budgetary income.

Beyond KATA, the so-called Simplified Public Burden Contribution (EKHO)[22] is another cheap option for some designated categories of self-employed workers to pay lower taxes and contributions from 2006. It attracts a much lower number of workers than KATA,[23] since it was designed only for media workers and artists (professions listed by the law), working either in an employment relationship or as a self-employed person. The worker must pay 15% (pensioners only 11.1%) of all income up to a maximum of HUF 60 million per year, which includes all income taxes and social security contributions. In addition, the employer/client pays a further 20% of the worker’s gross income. The worker is entitled to health care and a pension, but not to cash benefits (e.g. sick leave benefits, paid maternity leave) and unemployment benefits.[24] Moreover, the pension is calculated on the basis of only 61% of the taxed income.[25]

To sum up the Hungarian legal framework regarding self-employment, I would underline the long standing tradition of the binary employment structure built on two codexes, the Labour Code for employees and the Civil Code for self-employed workers. Under the scope of the Civil Code, civil law contracts, and particularly personal service contracts, provide an unchanged, stable contractual basis for personal work relations beyond employment relationships. Self-employed workers are either individual entrepreneurs, or personally contributing (working) members of a business association, typically members of a limited partnership. They have full social security coverage, however, they can save money by opting out of these full social security rights by choosing a cheaper taxation form (KATA). As a next step, I continue with some statistics and trends in self-employment.

Measuring self-employment is always a rather difficult and problematic task, since the lack of clear concepts, overlapping groups of self-employed and limited data all make this challenging. Hungarian data is also quite scarce and unclear when it comes to internal divisions within self-employed workers. First, I will try to estimate the number of self-employed, and particularly that of individual entrepreneurs as the largest group of self-employed. At the same time, I will also focus on trends in the last 30, as well as the last few years. Second, I will also describe the recent boom in the number of KATA taxpayers. Overall, I will try to describe the benefits and practical importance of self-employment in the Hungarian labour market.

The rate of Hungarian self-employed workers is low on a European scale, and has been constantly decreasing over the last 30 years, except for the last few years. While the self-employment rate, compared to the overall working population, was as high as 20.42% in 1990, however, it slowly decreased year by year to its present level at 10.83%, which is half of the 1990 figure. Remarkably, OECD data shows slight growth in the last few years, which I suggest can be explained by the growing phenomenon of false self-employment generated by the new taxation rules of KATA. For the purpose of the OECD statistics, self-employment is defined as the employment of employers, workers who work for themselves, members of producer cooperatives, and unpaid family workers.[26]

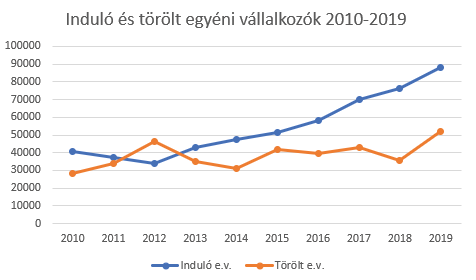

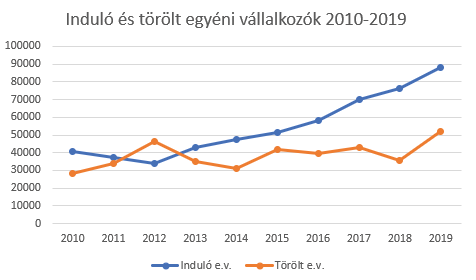

At the same time, the number of individual entrepreneurs has been radically increasing, and this change is most probably closely connected with the introduction of the new lump sum tax (KATA) in 2013. In recent years, the increase in the number of individual entrepreneurs was over 80,000 per year, which is quite high in a labour market of slightly more than 4 million workers. Overall, the number of individual entrepreneurs exceeded 530,000, which is the all-time highest number. It is also remarkable that the number of individual entrepreneurs is higher than that of business associations. Individual entrepreneurs are self-employed (some with employees), and also include some members (owners) of business associations, though this latter number is absolutely obscure.

Source: Opten: Már több az egyéni vállalkozó, mint a cég Magyarországon. 19.02.2020, https://www.opten.hu/kozlemenyek/mar-tobb-az-egyeni-vallalkozo-mint-a-ceg-magyarorszagon

Source: Opten, 2020.

The blurry legal frontiers between the employment relationship, self-employment and economically dependent work make it difficult to draw a clear picture of the proportion of different groups of self-employed workers in the labour market. In practice, genuine self-employment, bogus self-employment and economically dependent work function equally through civil law contracts as individual entrepreneurs, or as members of a business association.[27] The real size of these three subgroups of self-employed is often not elucidated by available data, as statistics primarily focus on the overall rate of self-employment, or the number of individual entrepreneurs. Exceptionally, the Hungarian Central Statistical Office has isolated data for 2017 on the self-employed with only one or more clients, which reveals that a third of the self-employed (140,000 workers) is dependent on one (decisive) client.[28] These workers are presumably either economically dependent workers or bogus self-employed.

The Small Taxpayer Entrepreneurs’ Lump Sum Tax (KATA) has become extremely popular among self-employed people in a very short time. Its adherents jumped from 75,000 workers in the first year (2013) to almost double at 140,000 in 2016, over 300,000 in 2017,[29] and 404,000 in June 2020,[30] which is almost 10% of the total Hungarian workforce. Since employees cannot use this form of taxation, and this is by far the most popular choice among self-employed workers, these numbers clearly illustrate the number of self-employed persons, but also the sudden increase in self-employment, particularly in false self-employment.

KATA is an excellent example of how poor financial policy can fuel the search for loopholes in labour law to achieve a higher income, even if it comes with very limited social security rights (e.g. pension). It is uncertain whether the new legal restrictions featuring a 40% extra tax above the HUF 3 million threshold will considerably affect the number of KATA taxpayers from 2021. Since the other tax alternatives are still more expensive than KATA, I predict that even if the recently skyrocketing increase stops, the number of those who choose this form of taxation will most probably stabilise at the present level.

Summarising the available data, the rate of self-employed is somewhere between 10% and 15% of all workers in the Hungarian labour market. This rate was above 20% in 1990, but dropped by half by 2020. In the last couple of years, we have experienced an increase in self-employment, specifically a jump in the number of individual entrepreneurs. This sudden rise in the popularity of entrepreneurship is, in my view, a logical consequence of the new ‘tax miracle’. Since KATA will be severely restricted as of 2021, continuation of the upsurge is dubious.

The first and second chapters above outlined the legal environment and practical importance of self-employment in Hungary. In this chapter, I will focus on labour law protection and social security rights of self-employed workers.

In Hungarian law there is no legal definition of self-employed workers. Moreover, even a widely accepted, uniform academic notion has not been elaborated, since labour law scholars even today use vague or varying concepts when writing about this labour market phenomenon.[31] Before the implementation of the EU Directives on equal treatment and working conditions, the lack of this definition went unremarked in academic literature. Thus, EU labour law harmonisation, particularly the clarification of the personal scope of Directive 86/613/EEC,[32] was the only reason that the definition of self-employment was scrutinised in Hungarian law. Beyond EU law harmonisation, it did not seem necessary to have such a definition, since it would not have had any theoretical or practical function.

There is no doubt that the notion of self-employment includes civil law contracts of individual entrepreneurs, individual firms and personally contributing members of business associations (dominantly limited partnerships), regardless of whether they have employees or not. In practice, individual entrepreneurship is the most dominant form of self-employed work and among entrepreneurs who employ others.[33] Some argue that only individual entrepreneurs with no employees are truly self-employed. In my opinion, employment of others is not an exclusive and decisive factor.

If we base our theoretical system on the binary model, we can conclude that self-employed workers are those who do not work under the aegis of an employment contract. Therefore, I argue that casual workers are not self-employed, since casual work, called ‘simplified employment’, is categorised by the Labour Code as an atypical employment relationship,[34] and it is in fact characterised by a certain level of personal subordination. Furthermore, the Eurofound database on self-employment includes members of cooperatives in self-employment.[35] However, the various types of cooperatives (social, student and pensioner cooperatives) may function as employers and are often similar to temporary work agencies, although with relaxed employment protection (Kártyás 2019). So I would exclude members of cooperatives from self-employment with regard to the special Hungarian legal environment.

In summary, there is no legal definition of self-employment, and even the academic literature is not uniform and clear-cut in relation to this concept. Self-employed workers are those who do not work under an employment contract. As a consequence of the binary structure of work relations, the civil law contract is the only contractual form of self-employed activity. Casual workers are formally employees, so they are definitely not self-employed workers. Members of various forms of cooperatives are not clearly employees, but the cooperatives often operate similarly to employers, or even temporary work agencies. Consequently, the notion of self-employment includes civil law contracts of individual entrepreneurs, individual firms and personally contributing members of business associations, depending on who you ask, with or without employees.

Hungarian employment law is based on the concept of “all or nothing”, since employees are entitled to all employment protection mechanisms after signing the employment contract, but self-employed workers have zero employment rights under the scope of the Civil Code by signing a civil law contract (personal service contract or work contract). The Civil Code provisions on these two contractual employment types[36] settle legal issues such as instructions and their refusal, representation, supervision, information obligation, fees, termination, etc. However, these rules do not ensure any employment protection for the worker. At the same time, there are no restrictions at all, for instance on possible activities or work duration, so these contracts may be used any time and without further conditions.

Hungarian employment laws are predominantly based on the employment relationship as the legal basis of rights and obligations. Since self-employed workers do not fall under the scope of these employment related laws, they are not entitled to employment protection under most of the employment related acts. Labour inspection is a good example, as the Labour Inspection Act covers only employees and not self-employed workers.[37] The same is true for collective labour rights, since the self-employed cannot conclude collective agreements[38] or strike.[39]

However, there are three notable exceptions when the scope of the employment protection law is not restricted to employees, but covers self-employed workers. First, the Equal Treatment Act may be applied to self-employed workers under the scope of civil law contracts.[40] Second, the scope of the Occupational Safety Act[41] is extended to any “organised work”, irrespective of the legal nature of the work relations. Third, security personnel[42] is an intermediate labour law category (between an employment relationship and self-employment) with some weak employment protection on working time and rest periods,[43] but without real relevance and remarkable numbers. Finally, self-employed workers have social security insurance as well, which is the topic of the following subchapter.

Self-employment is above all price sensitive, so the cost of working outside of traditional employment is the key factor in employers’ choice of the contractual form of work. The cost for both employers and employees from self-employment consists of taxes and social security contributions. The level of the social security contribution defines the quality of social services, since they are financed by payments made by the worker and employer/client.

As I have already described above, self-employed workers have basically two options in this respect. First, they can opt for full social services coverage, however, this is the most expensive legal form of work. Second, they can opt out of the general social security scheme by choosing the new taxation form (KATA), but this comes with limited services. It must be emphasised that limited social security coverage and particularly pension rights are the price of this low public burden. As already mentioned in Chapter 2 with respect to statistics regarding self-employment, Hungarian self-employed workers mostly choose the cheaper solution even if this decision has very negative consequences on present and future social benefits, particularly on their expected pension rights. Below, I will briefly elucidate the difference between these two options with a special emphasis on social security rights.

In the general scheme, self-employed persons pay the same contribution and are entitled to the same social security services as employees. All contribution-payers are insured against all risks, without exception. In the case of self-employed workers, there is an obligation to register with the social security authority in order to be entitled to all social services.

Within the cheaper KATA scheme, the ‘small taxpayer’ self-employed worker is considered to be an insured person by social security, and has pension, health and unemployment insurance.[44] However, the basis for calculating any social security benefit is a comparatively smaller amount (circa EUR 300). Therefore, all social benefits, such as the job seeker’s benefit and old age pension, accruing to these self-employed ‘small taxpayers’ is very low.[45] If we take the example of a self-employed worker with a monthly income of HUF 370,000 (EUR 1,200), their net monthly income is EUR 400 higher than would be the case if they were an employee. However, their pension will be almost EUR 400 euros less per month if we use the present pension regulation as the basis for our calculation.[46] We must see this phenomenon as a real time bomb in the pension system, as a large number of elderly people will have no real pension in the near future (when this group of self-employed people retires).

These very popular reduced schemes are quite problematic, since they impose a much lower public burden on self-employed workers. However, the social rights they are entitled to are also very limited. The most crucial disadvantage of these trends for society as a whole lies in the low pension, which will leave a considerable and increasing proportion of the working population without a real income after reaching retirement age. So, the social security of self-employed workers is fully guaranteed on the surface, but more and more of them ‘sell’ their rights to a future pension income for a higher net income now.

Therefore, a major revision of this statutory two-pillar (general and ‘cheap’ schemes for the self-employed) system is highly desirable. The high level of social burden is a key issue here, thus the high social contribution should be gradually (further) decreased for employees and self-employed workers alike. At the same time, the cheap schemes should be aligned to the general one with respect to taxes and contributions. This policy would strengthen the labour market position and the attraction of employment relationships and employment law. Some steps have been taken in this direction by lowering social security contributions and increasing KATA. However, the social rights of self-employed persons under the cheap schemes should also be improved, particularly as regards old age pension. This could be achieved by a higher contribution basis, or promoting their membership in a voluntary pension fund. Therefore, there are several options to deactivate the ‘self-employed pension bomb’.

As has been stated, there is no clear data on the number of false self-employed workers. According to my estimations, these individuals represent a considerable part of the self-employed: self-employment as a whole is estimated between 11–13% of all workers,[47] and a third of them (around 4% of all workers) is dependent on one (decisive) client.[48] Moreover, the number of individual entrepreneurs has dynamically increased in the past few years as a consequence of the cheap employment option offered by the new form of taxation (KATA). Many of these “new entrepreneurs” have probably opted out of employment relationships with the sole purpose of saving money for both parties (employee and employer) through this legal change in status from employee to self-employed.

False (bogus) self-employment is not a new phenomenon. It has always been present in the Hungarian labour market, and has been addressed as a fundamental problem in legislation several times since the return to the market economy in 1990. The fight against false self-employment (usually called disguised employment) has come to the forefront of employment legislative policy again and again in the last 30 years depending on each government’s policies and political agenda.

In this context, we can highlight the following legislative measures in the fight against this disadvantageous labour market phenomenon. Although they touch upon seemingly different topics, they have at least two aspects in common. The first shared feature of these legislative acts is that they all relate to the cost of self-employment through taxation, contributions, applicable labour laws, fines and punishment. Obviously, legislative policy is constantly facing a vicious circle: self-employment must be cheap to create jobs, but at the same time it must be controlled by higher costs. This leads to an oscillating employment legislative policy of tightening and loosening.

Another common feature of these legislative measures is how they exclusively target the employer. Even though both employers and employees alike save a lot of money by disguising employment in a cheaper legal form, the law punishes only the employer. The dogmatic basis of this solution is that the worker is personally and economically subordinated to the (often quasi) employer, so the contractual choice is basically made by the employing party. The increased tax (see point d) below is an exception in this regard, as this measure has an equally negative effect on the income of the worker as well.

In 1997, a separate law[49] introduced casual work in Hungarian employment law with the aim of tackling high unemployment and decreasing illegal forms of work. Casual work contracts were designed to create a very cheap and flexible contractual form, which is targeted at workers performing undeclared work as well as those engaged in false self-employment. If the law successfully increased the number of (declared) casual workers, it would increase tax revenues and social security contributions while strengthening their employment and social security rights.

However, the flexible regulation of casual work may also have an unwanted side effect. Namely, it may also lure employees from typical and atypical employment relationships, as casual work is much cheaper and comes with very limited employee rights. Replacement of employment relationships with casual work leads to lower budgetary income and the loss of most of the worker’s employment protection. So casual work is also a sort of disguised employment, even if casual work is de jure an employment relationship. Casual work is even cheaper than self-employment and provides a bit more employment protection. However, its length is strictly limited to 5 continuous days, 15 days per month and 90 days per year,[50] so it may be only used for shorter periods of time.[51] Without these limitations, casual work would certainly be the number one choice of employers due to the extremely low social charges: employers pay approx. EUR 3 per day for both taxes and contributions combined, and in exchange employees are entitled to a fragment of social security services.[52]

Disguising employment through false self-employment has always been unlawful, but the very first explicit prohibition was inserted in the Labour Code as late as 2003.[53] At the moment, the Labour Code does not prohibit false self-employment expressly, but explains only that “false agreements shall be null and void, and if such an agreement is intended to disguise another agreement, it shall be judged on the basis of the disguised agreement.”[54]

The legal basis of this implicit prohibition is the long existing judicial concept of the employment relationship, as the legal definition of the employment relationship was not included in the Labour Code before 2012.[55] Despite the previous lack of a legal definition, there has always been a sophisticated judicial test on the differentiation between bogus and genuine self-employment and on the national notion of an employment relationship. This test has been elaborated in recent decades by the labour courts and particularly the Supreme Court. On the basis of this extensive case law, a ministerial guideline introduced the theoretical system of primary and secondary characteristics of the employment relationship.[56] Even if this guideline was repealed in 2011,[57] this concept of primary and secondary features of employment still has some influence on legal practice. Assessment of the legal relationship between the parties (employee versus self-employed) is still often raised in legal disputes, particularly in litigation on unfair dismissal by the employer and the employer’s liability for damages. The application of labour law rules on termination of employment and liability for damages implies a certain financial burden on the employer.

Labour inspectors and tax inspectors are entitled to evaluate the legal relationship between the worker/employee and client/employer. If the inspector finds that the real and effective contractual relationship between the parties is that of an employment relationship, the employer may be fined both by the tax inspector and the labour inspector. The amount of the labour fine was increased in 2005[58] to create a real dissuasive effect. However, the number of labour inspectors is a key issue here, since the lack of adequate personnel leads to a low number of inspections. In the last 20 years, we have seen first an upsurge and later a slump in labour inspection staff, which considerably weakened the effectiveness of inspection.

As has been discussed exhaustively above, Hungarian financial (taxation) policy has been quite active in creating tempting tax systems for self-employed workers with extremely low social charges. The extraordinarily price sensitive phenomenon of false self-employment has been energised by these soft policies. This mistake was supposed be handled by the new measure, which imposes an extra 40% income tax on income over HUF 3 million from the same employer[59] as of 2021. This amendment of KATA will considerably increase the price of this form of work, which may noticeably moderate its financial attractiveness.

We can draw some lessons from the efforts of the last 30 years. Above all, false self-employment is a widely existing and even growing phenomenon in the Hungarian labour market. Its primary aim is to cut the cost of employment in order to maximise the income of the employer and employee, who is often an ally of the employer in this scheme against the state (budget). Legislation has already used several methods to combat civil law contracts, which in fact disguise employment relationships. Legislative measures include the creation of cheap alternatives, increased taxes and fines, legal prohibitions, judicial tests and so on. The common feature of these heterogeneous legislative steps is an effort to increase the cost of self-employment. However, this state policy is far from consistent, as it is counterbalanced from time to time by totally opposite fiscal measures with the objective of creating new jobs through cheap forms of entrepreneurship. KATA is an excellent example of why this is not effective in the long run.

The Hungarian model of legal relationships with respect to work consists of two contractual forms: employment contracts with full employment protection and civil law contracts without any protection in labour law. Self-employment covers rather different employment arrangements: genuine self-employment, false self-employment (disguised employment) and economically dependent work. Collectively, self-employed workers represent around 11–13% of the total workforce, however, the proportion of these internal classifications (e.g. the rate of false self-employed) remains unclear.

The binary model of employment relations is based on the concept of “all or no protection”. Since the self-employed all work under the scope of the Civil Code (typically through personal service contracts), they are not entitled to any employment rights. Notable exceptions are social security, occupational health and safety and equal treatment. Social security is rather tricky though, as self-employed workers can make a deal with the state to exchange their social security rights (like a future pension) for higher current income. This “deal” is achieved via the new taxation form of KATA, which provided an incredible impetus to the increase of (false) self-employment in recent years. The habitual response of the state is increasing the cost of employment, which completes the vicious circle of business as usual in a game of tug of war.

Brodie, Douglas. 2005. “Employees, workers and the self-employed.” Industrial Law Journal 34(3): 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1093/indlaw/dwi017

Casale, Giuseppe. 2011. The Employment Relationship. A Comparative Overview. Geneva: Hart Publishing.

Countouris, Nicolas. 2007. The Changing Law of the Employment Relationship. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

Davidov, Guy. 2005. “Who is a worker?” Industrial Law Journal 35(1): 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/ilj/34.1.57

Deakin, Simon. 2006. “The comparative evolution of the employment relationship.” In Boundaries and Frontiers of Labour Law: Goals and Means in the Regulation of Work. 89–108. Ed. by Guy Davidov, Brian Langille. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Gyulavári, Tamás. 2014. “A bridge too far? The Hungarian regulation of economically dependent work.” Hungarian Labour Law E-Journal 1, http://hllj.hu/letolt/2014_1_a/01.pdf (accessed: 23.09.2020).

Gyulavári, Tamás. 2019. “Structure and Social Protection of the Self-employed Society: An Eastern-European Perspective based on Hungarian Experience.” In Social Security Outside the Realm of the Employment Contract: Informal Work and Employee-like Workers. 162–176. Ed. by Mies Westerveld, Marius Olivier. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788113403.00016

Gyulavári, Tamás. 2020. “Casual work laws in Eastern Europe.” In Festschrift Franz Marhold. 549–560. Ed. by Elisabeth Brameshuber, Michael Friedrich, Beatrix Karl. Wien: MANZ’sche Verlags- und Universitätsbuchhandlung.

Jakab, Nóra. 2015. “Munkavégzõk a munkavégzési viszonyok rendszerében.” Jogtudományi Közlöny 70(9): 421–432.

Kártyás, Gábor. 2019. “Atipikus munkaviszonyok.” In Munkajog. 424–425. Ed. by Tamás Gyulavári. Budapest: Elte Eötvös Kiadó.

Pennings, Frans. Claire Bosse. Eds. 2011. The Protection of Working Relations. A Comparative Study. Alphen aan den Rijn: Kluwer Law International.

Szekeres, Bernadett. 2018. “Fogalmi zűrzavar a munkajogtudományban: az önfoglalkoztatás problematikája.” Publicationes Universitatis Miskolcinensis 36(2): 472–484.

Legal acts

Act 4 of 1959 Civil Code (not in force from 2014).

Act 7 of 1989 on the right to strike.

Act 4 of 1991 on the promotion of employment.

Act 22 of 1992 on the Labour Code.

Act 93 of 1993 on occupational safety.

Act 75 of 1996 on Labour Inspection.

Act 74 of 1997 on employment with Casual Work Booklet and on its public burdens.

Act 80 of 1997 on pensions.

Act 125 of 2003 on equal treatment and promotion of equal opportunities.

Act 120 of 2005 on the simplified public burden contribution.

Act 133 of 2005 on security guards and private detectives.

Act 155 of 2005 on amending the Labour Inspection Act regarding labour fines.

Act 115 of 2009 on individual entrepreneurship and individual company.

Act 130 of 2010 repealed all guidelines from 2011.

Act 1 of 2012 Labour Code https://www.ilo.org/dyn/travail/docs/2557/Labour%20Code.pdf (accessed 23.09.2020).

Act 147 of 2012 on the Small Taxpayer Entrepreneurs’ Lump Sum Tax and Small Company Tax.

Act 5 of 2013. Civil Code (in force from 2014) https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/96512/114273/F720272867/Civil_Code.pdf (accessed 9.09.2020).

Council Directive 86/613/EEC of 11 December 1986 on the application of the principle of equal treatment between men and women engaged in an activity, including agriculture, in a self-employed capacity, and on the protection of self-employed women during pregnancy and motherhood. OJ L 359, 19.12.1986.