https://orcid.org/0009-0003-7669-4491

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-7669-4491

Abstract. The objective of the chapter is to analyse legal regulations concerning self-employed activity in force in Germany and Austria. First and foremost, the author presents the scale of self-employment in the relevant countries and the sources of its legal regulation. He goes on to characterize the definition of a self-employed person and the categories of workers that fall within its scope. Furthermore, the author analyses the scope of protection guaranteed by German and Austrian legislation to the gainfully self-employed under individual and collective labour law. The last part of the chapter is devoted to the phenomenon of “bogus self-employment” and the legal mechanisms designed to combat it.

Keywords: self-employment, employment relationship, German law, Austrian law, economic dependence, bogus self-employment

Streszczenie. Celem rozdziału jest analiza regulacji prawnych dotyczących samozatrudnienia w Niemczech i Austrii. Na wstępie autor prezentuje skalę wykorzystania tej formy aktywności zarobkowej we wskazanych krajach oraz źródła jej regulacji prawnej. W dalszej części charakteryzuje definicję osoby samozatrudnionej oraz kategorie wykonawców, które mieszczą się w zakresie tego pojęcia. Autor analizuje również zakres ochrony gwarantowanej przez ustawodawcę niemieckiego i austriackiego osobom pracującym zarobkowo na własny rachunek na gruncie indywidualnego i zbiorowego prawa pracy. W końcowej części rozdziału przedstawione zostało zjawisko „fikcyjnego samozatrudnienia” oraz mechanizmy prawne służące do jego zwalczania.

Słowa kluczowe: samozatrudnienie, stosunek pracy, prawo niemieckie, prawo austriackie, zależność ekonomiczna, samozatrudnienie fikcyjne

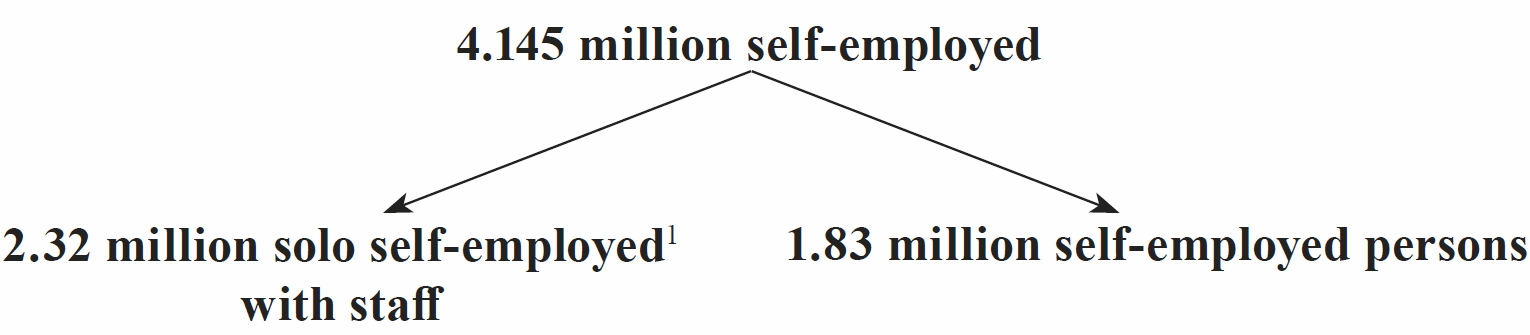

The share of self-employed in the working population in Germany has remained unchanged for many years at around 10% (Brenke, Breznoska 2016, 9, 14). In 2016, there were 4.145 million self-employed in Germany. They can be broken down into the solo self-employed and self-employed with staff.

(2.32 million solo self-employed[1])

This is considerably less than the EU average and, more importantly, much less than in Poland. Where there have been fluctuations, they have ranged between 10% and 12%. The proportion of women rose from 33% to 37% between 2000 and 2011. The strong increase in the number of solo self-employed has resulted in particular from state subsidies (so-called Ich-AGs) and liberalisation of the law on crafts.

The reasons for choosing to become self-employed originate with the employee, as well as from the legal environment and economic situation.[2] Some people do not enjoy working in a company environment. They want to make their own decisions and do not want to take orders from someone else, or be trapped in a foreign organisation (Institut 2018, 15). Others have entrepreneurial ambitions and expect to make more money than they do as employees. How many people decide to become self-employed also depends on the legal environment. When Germany provided subsidies for so-called Ich-AGs a few years ago, the number of self-employed increased (Brenke, Breznoska 2016, 13). The risk of self-employment was reduced thanks to the receipt of a monthly subsidy.

The legal framework is also important in that tightening of labour law leads companies to switch to other forms of employment relationships, increasingly to self-employment. General economic development means that a growing number of people expect to achieve success by becoming entrepreneurs. Thus, the number of self-employed people also reflects the economic development of a country. In 2016, approximately 13% of men and 7% of women were self-employed (Bonin, Krause-Pilatus, Rinne 2018, 15). In Germany, the number of self-employed is highest at the highest qualification level. Self-employment is also high risk because of the nature of entrepreneurial activity. After one year, between 50 and 60% of self-employed give up their self-employment status. In comparison with employees, there is a wide range of income levels.

Among self-employed persons, solo self-employed persons form a separate category (see 4.3.). They can be divided into those who work mainly for one client or for several clients, and by whether they work full or part time (Uffmann 2019, 360, 362). Solo self-employed are not evenly distributed across all occupations (Brenke, Breznoska 2016, 10, 35; 320 f.). Rather, they are found in particular in the following occupational groups:

Solo self-employed are largely employed on a part-time basis. The share of solo self-employed in the number of employed persons increases with vocational training – 92% are men and 8% women (Brenke, Breznoska 2016, 77 f.). The median monthly income of solo self-employed is the same as that of employees. In contrast, the median income for self-employed with employees is 1.75 times that of employees. Within the group of solo self-employed, there is a significant difference between those with a high school diploma and others. Otherwise, the results by gender, economic activity and regional distribution are essentially the same.

IT specialists, estimated at 100,000, are a special group among the solo self-employed (Brenke, Breznoska 2016, 23; Bonin, Krause-Pilatus, Rinne 2018, 9, 28; Uffmann 2019, 360–361). Members of this group have been among the top earners for years (Institut 2018, 25). More than 80% are entitled to a statutory pension (Institut 2018, 26). An English study refers to them as “independent professionals” (iPros).[3] They represented 0.8% of employees in Germany in the 2004–2013 study period.[4]

All statistical statements are subject to the uncertainty associated with the lack of agreement on the definition of an employee (see 6.4.). In any case, it is necessary to operationalise the boundaries in legal precedents and literature, because, in general, vague terms are used that are open to different interpretations (Dietrich 1996, 40 ff., 59 ff.)[5] making valid empirical research difficult. A second issue comes from the fact that no distinction is made between an individual’s primary and secondary job,[6] although the amount of protection is different.[7]

The legal basis for the right of self-employed persons derives from EU law, the constitution and ordinary law.

Union law comprises in particular economic law and a large part of labour law, with the exception of the areas mentioned in Article 153(5) TFEU. Union legislation is partly enacted by means of regulations, but predominantly by means of directives. Insofar as Union law does not refer to the law of the Member States with regard to the concept of employee, the CJEU forms its own definition by way of “autonomous definition” (Henssler, Pant 2019, 321, 325; Wank 2017a, 235 ff.), which is then binding for all Member States. In essence, the unhelpful Lawrie-Blum formula applies, according to which an employment relationship exists if “a person performs services of some economic value for and under the direction of another person in return for which he receives remuneration”.[8] Incidentally, the CJEU’s definition in this case deviates considerably from the concept of employee that is widespread in Germany and also includes civil servants, soldiers and judges (Temming 2016, 158 ff.; Wank 2018a, 327, 337 f.). The CJEU increasingly uses the very broad concept of employee in the law on the free movement of persons as a basis for all labour law directives, although these pursue quite different purposes.[9] If a directive serves to concretise a fundamental right, the CJEU does not feel bound, even by the explicit reference to the concept of workers of the Member States, but rather develops its own “semi-autonomous” (Brose 2020, 13.22) concept of worker in free creation of law (Junker 2016, 184, 192 f.; Temming 2016, 158 ff.; Wank 2016, 143; Wank 2018c, 327 ff.; Wank 2018b, 21 ff.). A description of national law on the concept of employee is incomplete without taking Union law into account. The idiosyncratic interpretation of the CJEU leads to a split legal situation: insofar as German law is based on EU law, the CJEU’s concept of employee applies. If this is not the case, the German concept remains unchanged (Boemke 2018, 1; Preis, Sagan 2013, 26 ff.).

Though EU law refers to the law of the Member States with regard to the concept of employee, this law applies in principle. Only if a Member State abusively excludes certain groups of persons from the definition of employee can the CJEU include them in the definition of employee by way of abuse control (Wank 2018b, 21, 22, 26). Moreover, the CJEU is often not satisfied with abuse control, but invokes effet utile to invent its own concept of employee, for which it lacks the basis of legitimacy (Wank 2018b, 21, 26 f.).

To transpose Union law into German law, the German legislature can either create its own laws for the groups of persons not covered by the German concept of employee, which correspond to those for employees, as is predominantly done in civil service law; or it can use the concept of “Beschäftigter” in labour law, which then expressly includes civil servants and others (see 3.5.); or in a special law, by virtue of an interpretation in conformity with Union law, civil servants and others are also included in the concept of employee.

In the constitution, the right to independent professional practice is guaranteed in Article 12 GG. The Federal Constitutional Court takes Article 12 of the “Basic Law” (GG) as a uniform fundamental right that refers both to the choice and exercise of a profession (BverfG, BVerfGE 87, 316). According to this, Article 12 of the Basic Law applies to everyone and to all professions. Thus, the entire range of self-employed activity is covered. Constitutional law does not require a separate definition of an employee (Wank 2017a, 240 f.).

Legal bases are also found in ordinary law (in contrast to constitutional law) in various labour laws, which distinguish self-employed persons from employees, as well as in commercial and general civil law.

In the field of commercial law, special mention should be made of cartel law, which also helps small-scale self-employment businesses to the extent that it prohibits the exercise of abusive market power (Deinert 2015, para. 45 ff.). In addition, commercial law contains a wealth of regulations for individual professionals such as lawyers, architects, brokers, doctors, etc.

Apart from that, the regulations of general civil law apply to the self-employed exercise of certain professions. The basis for this is the constitutionally guaranteed freedom of contract, Article 2. 1 of the Basic Law (BVerfG, BVerfGE 65: 210; BVerfGE 95: 303). The BGB contains special regulations for a whole range of professions, each of which is based on a specific type of contract. These include a purchase contract (sec. 433 BGB), contract of service (sec. 611 BGB), contract for work (sec. 631 BGB), etc. In addition to the special regulations, the general and special law of obligations applies to all these contracts. It is always applied if no special regulation for this type of contract is provided by law.

The legal basis in practice usually consists of general terms and conditions. They are not state law and therefore not mandatory, but of great practical importance. When consulting the content of general terms and conditions in sec. 305–310 BGB, a distinction is made between terms and conditions that are applied to a consumer and those terms and conditions that apply to the self-employed. In the second case, legal control does not apply because, according to the model of the law of obligations, the self-employed are responsible for themselves. There is a lower threshold for judicial review than in the case of general terms and conditions if a contractual regulation is immoral and violates sec. 138 para. 1 BGB.

With regard to the protection of self-employed persons, a distinction must be made between protection with regard to the contractual relationship, quasi-employment law protection and social security law protection. A more detailed discussion of this issue can be found below under 5.

In addition to the definition of employee/self-employed persons, the definition of pseudo-employees is added as a subgroup of self-employed persons. They are mentioned in a number of labour laws; it is questionable whether and to what extent other laws are applicable by analogy (Schubert 2004). The Federal Act on work at home[10] should also be mentioned here, which contains separate regulations for a certain group of self-employed persons (Preis 2020, 330 HAG).

In addition to general civil law and labour law, social security law must also be taken into account. Protection against adverse life events can be achieved either through labour law (e.g. continued payment of wages by the employer in case of illness) or through social insurance law (e.g. sickness benefits from the health insurance fund) (Wank 1988, 336 ff.). In principle, self-employed persons are not included in the statutory social security system in Germany (Becker 2018, 307 ff.; Maier, Wolfgarten, Wolfle 2018, 259 ff.); however, there are efforts to include them in the pension insurance system (see 5.3.).

Whether an employed person is covered by the law on self-employed persons or by the law on employed persons depends on the definition of an employee. Thus the self-employed person as a concept stands in opposition to that of the employee. Neither German nor Austrian law, nor for that matter the legal systems of other countries, offers a legal definition of self-employment. Whether or not self-employed persons can be correctly recorded therefore depends on whether the employee is correctly defined in contrast to the self-employed.

An exception is made in sec. 84 para. 1 sentence 3 HGB: “Self-employed persons are those who are essentially free to organise their activities and determine their working hours”.[11] From a legislative point of view, it is incomprehensible that this rule was retained even after the creation of sec. 611 a BGB. According to this, it appears that there is a general definition in sec. 611 a BGB, which is derived from the inversion of the characteristics in sec. 611 a BGB, and a special provision for commercial agents. This was not intended, however. The provision was taken over as sentence 3 in sec. 611 a BGB, but with a different wording: “Not bound by instructions”. This is misleading because according to sentences 1 and 2, personal dependence and foreign control are to be taken into account, which is not mentioned in sec. 84 HGB. The provision should be deleted and replaced by sec. 611 a BGB, including for commercial agents (Wank 2017a, 140, 147 f.).

Thus, whether self-employed persons can be correctly defined depends on whether the employee is defined correctly in contrast to the self-employed. In Germany, until 2017, this definition was based on the case-law of the BAG and literature on labour law. However, this case-law had some deficiencies.[12] It was not clear to what extent the aspects used in the case-law should be characteristics or circumstantial evidence, nor was the relationship of the individual characteristics or circumstantial evidence and their weighting in relation to each other clear. With the exception of a few judgements, which showed the connection between the concept of employee and the legal consequences attached to it in the field of labour law instead of in the field of self-employment law, there is still no teleological concept in the case-law. This is questionable considering the principle of equality in Article 3.1 of the Basic Law, because on the basis of this, application of the definition is partly arbitrary, for example, with regard to the teaching profession.

The same is largely true of labour law doctrine. Until recently, the predominant opinion referred to what the Reichsarbeitsgericht and Alfred Hueck allegedly said decades ago (and what is reproduced in misquotations, see Wank 1988, 29). without addressing the meaning or purpose of the definition.[13] Since sec. 611 a BGB came into force, this rule has been used as a basis without any in-depth examination of the deficiencies in the regulation. In any case, the view that the existence of a legal definition precludes interpretation, in particular a teleological interpretation, and existing characteristics should be applied formally and without any connection to the purpose of the law, is incorrect (Preis 2018, 817). Instead, the vague terms in sec. 611 a BGB require us to perceive Art. 3.1 of the German Constitution as a teleological interpretation.

Pseudo-employees are a subgroup of self-employed persons (see 4.2.).

In 2017, sec. 611 a BGB came into force, which contains a legal definition of an employee. The provision reads as follows:

Section 611 a Employment Contract. (1) The employment contract obliges the employee, in the service of another person, to perform work which is subject to instructions and determined by a third party and which is personally dependent. The right to issue instructions may relate to the content, performance, time and place of work. Anyone who is not essentially free to organise his activity and determine his working hours is bound by instructions. The degree of personal dependence also rests on the nature of the activity in question. An overall assessment of all circumstances must be made in order to determine whether an employment contract exists. If the actual performance of the contractual relationship shows that it is an employment relationship, the designation in the contract is irrelevant.

(2) The employer is obliged to pay the agreed remuneration.

The provision contains a lot of legislative errors and ambiguities; a transfer to the legal systems in other countries cannot be recommended.

The BGB now states:

Division 8 Particular types of obligations

Title 8 Service Contract and Similar Contracts

Subtitle 1. Service Contract

The order is as follows:

Section 611: Typical contractual duties in a service contract

Section 611 a: Employment contract

This system is not suitable for the task at hand (Wank 2017a, 140 f.). According to a systematic interpretation of the law, contract of service is the generic term, i.e. a service contract in the broader sense. The service contract in the narrower sense and employment contract are sub-concepts. In reality, however, the employment contract is not (only) a sub-category of the contract of service, but an independent type of contract, which can be contrasted with all independently exercised contracts in section 8 of the BGB Special Part. Thus, for example, a treatment contract concluded by a self-employed person (sec. 630a–630h BGB) is also a contract of service which must be distinguished from the employment contract. The opposing term is not the person that performs a contract of service, but the self-employed person in general. It is also difficult to differentiate between the contract for work and services (Greiner 2015, 218; empirical on the contract for work and service: Brenke and Breznoska 2016; Arntz et al. 2017) and temporary work (Wank 2021, sec. 1 AÜG, para. 19).

If the employment contract is regarded as a subset of the contract of service, then those characteristics which apply equally to the contract of service and the employment contract must be “placed before the parentheses”. The definition of the employment contract may then only contain those characteristics which distinguish the employment contract from the contract of service. A repetition of the characteristics in the contract of service and the employment contract is only justified and useful if the employment contract is defined as an independent contract category and not as a sub-category of the contract of service. In this respect, the regulation in sec. 611 and 611 a BGB with its superfluous repetitions has failed (Wank 2017a, 140, 143).

Both types of contract are contractual and not public law arrangements. The reference to the private-law nature of both contracts, which is customary in case-law and literature, is unnecessary. Both contracts concern the performance of services. Sec. 611 BGB says: “a person who promises services” and “services of any type may be the subject matter of service contracts”, and sec. 611 a BGB says: “the employee is obliged to perform work in the service of another…”. Both sections state that the person to whom services are rendered is obliged to pay the agreed remuneration. The repetition of “private contract”, “services” and “remuneration” in sec. 611 a BGB is therefore superfluous and misguiding.

If one wanted to infer from sec. 611 a of the Civil Code how the service provided by a person performing a contract of service differs from that of an employee, the new provision does not offer any specific characteristic for this, but rather three parallel characteristics, namely “personally dependent”,[14] “subject to instructions” (Boemke 1998, 285, 301 ff., Maties 2020, § 611 a BGB, para. 95 ff.; Preis 2021, § 611 a BGB, para. 35 ff.) and “determined by others” (Preis 2021, § 611 a BGB, para. 41 ff.). How they relate to each other is unclear and in any case cannot be inferred from the text of the provision.[15] The fact that a dictionary of synonyms is offered in a law instead of a characteristic is based on the fact that the legislature did not create its own legal definition, but copied formulations from the BAG’s guiding principles. Of course, a court is free in its choice of words and can offer several expressions in the hope of somehow conveying the proper meaning. In contrast, a legislator should express themselves clearly.

(a) The literature deals benevolently with this misguided legislation in such a way that it reads a meaning into the unstructured wording. According to legal doctrine, personal dependence is a generic term. The sub-concepts are therefore the obliged [to carry out] instructions and external control or integration.

In case-law and the literature, “personal dependence” is often understood to mean that “economic dependence” is not important. This is as correct as it is banal, if one understands economic dependence in the same way as representatives of the ontological concept, as if it depended on one’s own assets and also included suppliers. None of the numerous authors who have attempted a teleological definition of the concept holds this view.[16] Instead, it is appropriate (Wank 2017a, 140, 145, 152) to focus on the possibility of taking entrepreneurial decisions (BSG 18.11.2015, BSGE 120, 99; Wank 2017b, 293 ff.) on one’s own account (Wank 2017b, 289 f.). The generic term “personally dependent” is superfluous and therefore misleading, since everything that matters is expressed in terms of binding instructions and external control or integration.[17]

(b) With regard to binding instructions, sec. 611 a para. 1 sentence 2 BGB states that they may relate to the content, performance, time and place of the activity, while sentence 3 immediately afterwards reduces the binding instructions to “free organisation of one’s activity” and “determination of one’s working time”.

The truly important statement – that it is not a matter of issuing any instructions, but business instructions (Wank 2016, 143, 161) – is omitted, as is the statement that the possibility of issuing instructions as provided for in the contract is already sufficient (Wank 2017b, 389 ff.).

If an instruction may equally be given to a self-employed person and to an employee, the difference depends on the intensity of the instruction – if there is no room for independent entrepreneurial decisions, the formal situation of a self-employed person is not sufficient to make them self-employed.

Particularly in the case of liberal professions, the concept of a “employee not bound by instructions” is recognised in case-law and the literature. According to the BSG, this is characterised by “functional, service-oriented participation in the work process” (E.g. BSG 4.06.2009; NZA 2019, 1583, 4.6.; NZS 2019, 785). This is an employee who lacks the decisive characteristic and is nevertheless an employee (Preis 2021, § 611 a BGB, para. 65 f.). This shows that binding instructions must be understood differently than according to the prevailing opinion and that to be an employee cannot only depend on binding instructions.

If the instruction is based on constraints related to work performance or legal requirements, this applies equally to employees and self-employed persons and does not contribute to the definition.[18] Moreover, digitisation means that many instructions in the usual form are no longer needed (Brose 2017, 7, 11; Deinert 2017, 65, 67; Günther, Böglmüller 2015, 1025, 1028; Wank 2018c, 61 ff.).

❲c❳ Foreign control can be understood as integration (Preis 2021, § 611 a BGB, para. 4: sub-term of subordination under orders; Wank 2017b, 282; Wank 2017a, 140, 143 f., 150); into a foreign organisation (Fischels 2019a, 273 f.; Preis 2021, § 611 a BGB, para. 41; Schneider 2018, § 18, para. 32 ff.; Wank 2017a, 140, 143, 151). It is not clear what else might be meant by this (Deinert 2017, 65, 67; Preis 2018, 817, 824; Wank 2017a, 140, 142; opposite Hromadka 2018, 1583, 1585; Thüsing 2018, § 611 a BGB, para. 8: tautology). While the characteristic of integration was recognised for decades in case-law and throughout the literature, the BAG has abandoned it in more recent judgements without justification or has read it into the binding directives (critical: Uffmann 1989, 360, 366). It has been correctly retained in sec. 1 para. 1 sentence 2 AÜG. If it had been correctly formulated, sec. 611 a BGB should have read: “work subject to instructions within the framework of integration into the organisation of the contracting party”.

Section 611 a of the German Civil Code lists four areas in para. 1, sentence 2 to which instructions may refer.

(a) A very important characteristic, which has always been classified as very important in case-law and the literature, is whether the employee can organise their working time independently or whether it is imposed (Preis 2021, § 611 a BGB, para. 35 f.; Wank 2017b, 269 ff.). However, time management can be understood to mean many things (Wank 2017b, 270; empirical Dietrich, Patzina 2017, 45 ff.):

For all the characteristics mentioned, including time, the first question to be asked is always whether there are constraints based on the type of work or whether there are other ways of organising work (Wank 2017a, 140, 147). For example, a teacher employed as a self-employed person cannot decide independently when they want to teach lessons at school; the school must draw up a weekly schedule for teaching a class. In differentiating between the employed and self-employed, it is important to know whether the teacher can influence the timetable, for example, if they only want to teach on Mondays and Tuesdays. However, employed teachers (e.g. part-time) can also be allowed to influence the schedule.[19]

(b) The place of work is also an important distinguishing characteristic (Wank 2017b, 266 ff.; empirical Dietrich, Patzina 2017, 48 ff., 67). Here, too, location determinations must be excluded from consideration due to constraints. For example, a self-employed craftsman can only carry out certain construction work while on site. A music teacher, on the other hand, can choose whether the music lessons take place at their home or that of the client. This freedom of choice speaks for self-employment.

❲c❳ Section 611a of the German Civil Code (BGB) also gives instructions regarding the content and performance of the activity. This duplication is misleading. It overlooks the fact that a distinction must be made in the employment relationship between the employment contract itself, on the one hand, and the performance of the contract on the other. The nature of the work is determined by the contract. Any instruction by the employer is only permissible to the extent that it is within the scope of the employment contract (Wank, 2020, 4 ff.). There is room for instructions only insofar as they concern the performance of the contract. Performance refers to the place and time of work, but only to the nature insofar as the manner of work performance is regulated by instructions (Wank 2017a, 140, 146; empirical Dietrich, Patzina 2017, 61 ff.).

According to sec. 611 a para. 1, sentences 4 and 5 of the German Civil Code (BGB), what matters in all this is the specific nature of the activity (Wank 2017a, 140, 148; as concerns branches of activity Fischels 2019a, 229; Preis 2021, § 611 a BGB, para. 55 ff.; Wank 2017b, 373 ff.) and the overall consideration of all circumstances. Both can be mentioned in judicial texts, but have no place in a legal definition. The special characteristic of continental European legal definitions compared with those in the “Allgemeines Landrecht” for the Prussian states or in the Anglo-American legal system is that they feature the most abstract definitions possible, which cover a wide range of individual cases. It is therefore natural that the significance of the decisive characteristics and indications in the concept of employee vary according to the type of activity. In this respect, it goes without saying that an overall view is very important (Preis 2021, § 611 a BGB, para. 46; Wank 2017a, 140, 149).

However, the wording “overall view of all circumstances”[20] suggests erroneously that the law is based on the typological method (see 3.2.7.). Nonetheless, it can also be understood as a (superfluous) indication that individual elements of the term may be more or less strong and that an overall assessment must always be made (Preis 2020, § 611 a BGB, para. 46; Fischels 2019a, 113; Wank 2020b, § 11, para. 98).

If the actual implementation of the contract contradicts the designation in the contract, i.e. if, from an objective point of view, an employment contract is present contrary to a designation as a contract of service, then according to sec. 611 a, para. 1, sentence 6 BGB, what is actually carried out applies (Schwarze 2020, 38; Wank 2017a, 140, 149 f.; Wank 2017b, 257 ff.).

Although sec. 611 a BGB mentions individual prerequisites for the elements of a case in accordance with a class concept,[21] the view that the employee is a typus concept still holds in part.[22] That would mean: Any subsequent, even dispensable (Fischels 2019a, 80 ff.) characteristics can be used in any number with any content and weight.[23] On the contrary, the only correct approach is based on legal prerequisites and can be concretised by sub-concepts and indications (Wank 2017b, 253 ff.; see the scheme in Wank 2020c, 110, 118 and below g) bb).

Indications can also take into account the amount of remuneration, for example, as is done in some BSG judgements.[24] In this respect, but only in this respect, can one speak of a typus. However, to retain accuracy, there must also be a connection between all sub-characteristics and circumstantial evidence, and the aims of the law.

All new problems with the concept of employee were excluded from the creation of sec. 611 a BGB. Nothing is found on external managing directors, although this is urgently needed according to CJEU case-law. It also omits the issue of crowdworkers and other new forms of employment (critic: Preis 2018, 817, 818; Sagan 2020, 3, 8; Wank 2017a, 140, 153; Wank 2017b, 349 ff.).

In many cases, employees provide services for another person without this being based on an employment contract or any other contract under private law. This applies, for example, to: officials (Maties 2020, § 611 a BGB, para. 34 ff.; Preis 2020, § 611 a BGB, para. 132 ff.; Schneider 2018, § 18, para. 58 f.), soldiers, judges (Maties 2020, § 611 a BGB, para. 39; Preis 2021, § 611 a BGB, para. 132),[25] family helpers (Maties 2020, § 611 a BGB, para. 44 ff.; Preis 2021, § 611 a BGB, para. 137 ff.; Schneider 2018, § 18, para. 65), and prisoners (Preis 2020, § 611 a BGB, para. 136; Schneider 2018, § 18, para. 60). While for some of these groups of persons it is clear both under Union and German law that they do not have the status of employees (e.g. prisoners, family members), for others there is a divergence between the case-law of the CJEU and German law (e.g. civil servants, judges, soldiers, external managers of limited liability companies), which leads to split application of the law (Temming 2016, 158; Wank 2018a, 327, 336).

Some labour laws are not only applicable to employees, but also to other groups of people, such as pseudo-employees and civil servants. In this case, the law uses the generic term “Beschäftigter” (Forst 2014, 157; Maties 2014, 323, 325 f.; Richardi 2010, 1101; Wank 2017b, 226 ff.). This does not change the concept of employee.

Employees must be distinguished from self-employed persons not only in employment law but also in a number of other legal areas. These include employment law, social security law and tax law. In practice, this means that the employer has to pay social security contributions to the social insurance agency on the basis of the employment contract (both the employer’s contribution and, in their capacity as a payee, the employee’s own social security contributions). The same applies to the wage tax payable by the employee: the employee is the obligor and the employer is obliged to pay the tax office. Although a consistent definition should apply in this respect, social security law and tax law each use a separate concept of the employee.

The individual branches of social security are linked to the term “Beschäftigter”. This is misleading because the social insurance law concept of the “Beschäftigter” is partly different from the labour law concept. In labour law, the term “Beschäftigter” is used in some laws and includes both employees according to the general concept of employee and some additional groups of persons who are also subject to labour law (see above) (Richardi 2010, 1101, 1102; Wank 2017b, 226).

The concept of Beschäftigter is defined in sec. 7, para. 1 SGB IV: “Beschäftigung (“employment”) is non-independent work, especially in an employment relationship. Indicators of “Beschäftigung” are an activity carried out according to instructions and integration into the work organisation of the party issuing the instructions”.

The idea that the concept of Beschäftigter in social security law should be determined independently can be found widely in case-law and the literature.[26] There are differences between social security law and labour law, e.g. with regard to the fact that in social security law not only the welfare of the parties is at stake, but all of those who are affected by social security law.[27] It is preferable, however, in principle, to adopt the concept of employee in labour law (Kunz 2020, § 4, para. 2, 29). Even if there are justified deviations, it is not necessary to postulate a new concept of employee, but certain special rules of social security law can be established for individual cases (Wank 2020c, 110, 111).

In sec. 1, para. 1, sentence 1 of the Lohnsteuer-Durchführungsverordnung (Wage Tax Implementing Regulation), tax law defines employees as “persons who are or were employed in the public or private sector and who receive remuneration from this employment relationship or a previous employment relationship”. According to para. 2, sentence 2, this depends on whether “the active person is under the direction of the employer in the performance of his or her business will or is obliged to follow the employer’s instructions in the employer’s business organisation”, i.e. whether he or she is bound by instructions and/or integrated.

Sometimes the concept of employee is used for the same person by two legal fields, e.g. labour law and company law (Maties 2020, § 611 a BGB, para. 48 ff.), where only one legal concept can apply to an applicable area of law. Thus, according to the CJEU, external directors of private limited companies are employees, whereas the BGH and the BAG regard them as self-employed.[28] This instance of competition between legal areas[29] must be decided according to the fact that the more relevant legal area takes precedence, but the particularities of the other legal area must be taken into account (Wank 2018b, 21, 27; Wank, Maties 2017, 353 ff.).

Two different approaches to the definition of employee and thus self-employed can be found in the literature.

The definition of the prevailing opinion is based on a misquotation of a statement by Alfred Hueck. According to this statement, an employee is someone who, on the basis of a contract under private law, is obliged to carry out externally determined work in personal dependence in the service of another person (representative: Zöllner et al. 2015, § 5 para. 1).

In this view, the opposing concept to an employee in the present context is someone who works on the basis of a contract of service.

According to another opinion, the definition is not appropriate for two reasons. First, it is an ontological definition (Fischels 2019a, 27 f.; Wank 1985, 143 ff.). One defines according to outward appearance without inquiring into the meaning and purpose of the law and thus the characteristics. In contrast, a teleological definition is the only one permissible methodologically, i.e. a definition that establishes a connection between the term and the legal consequences connected with it (Fischels 2019a, 28 ff.; Wank 2020b, § 8 para. 16 ff.). This can only be achieved if specific economic dependence under labour law is either included in the definition as an additional characteristic or if the existing characteristics are understood teleologically in the sense that this specific expression of an economic dependence is taken into account.[30]

The opposite of the concept of employee is that of the self-employed person, who provides services for another person. The definition must be based on the meaning of this dual model of gainful employment and the different legal consequences attached to it (Wank 1998, 82 ff., 117 ff.). Anyone who freely chooses an entrepreneurial risk,[31] alongside opportunities and risks related to the respective contractual relationship, i.e. who has the opportunity to make entrepreneurial decisions on their own account, does not need the specific protection of labour law, but is subject to the law of the self-employed.

This is not, as some authors allege, a deviating concept that is impermissible in view of sec. 611 a BGB (Preis 2021, § 611 a BGB, para. 54, mixing aims of the law, terms, sub-terms and indications); rather, the purely formal formulation of sec. 611 a BGB – like any other legal concept – must be interpreted with regard to the underlying protective purposes of labour law, i.e. the teleological orientation of all terms, sub-terms and indications must be oriented towards the protective purposes of labour law (Preis 2021, § 611 a BGB, para. 54 – in opposition to para. 3).

A teleological definition also indicates that the employee should not only be distinguished from the employee, but also from other self-employed persons, such as contractors (Deinert 2017, 65 ff.; Henssler 2017, 65, 89 ff.; Wank 2021, § 1 AÜG, para. 18), as well as agency workers (Deinert 2017, 65, 69 ff.; Wank 2021, § 1 AÜG, para. 19).

When analysing whether self-employment or employee status exists, the following test scheme can be used (Wank 2020c, 110, 116 f.):

The question of how employees and self-employed persons are to be differentiated has not yet been satisfactorily clarified anywhere (Wank 2019, 131, 138). Even the legal definition in sec. 611 a BGB has not changed this. A teleological interpretation depends on what is regarded as the protective purpose of the labour law – all terms, sub-terms and indications of the definition must be geared toward the protective purposes. For example, an empirical study in 1996 compared three models: the BAG model (guiding concept: personal dependence), the alternative model (guiding concept: entrepreneurial risk) and the model of social insurance authorities (guiding concept: compulsory insurance and contributions) (Dietrich 1996, 2). In a follow-up study, the BAG model, the alternative model and the BAG-Plus model were also examined separately (Dietrich Patzina 2017, 86; see below 6, part one).

Neither the CJEU´s definition of an employee nor the definition in sec. 611 a BGB comply with elementary methodologic requirements. They refer to appearances instead of the aim of employment law. Moreover, they lack the differentia specifica between employee and self-employed (see 6.1.). A teleological definition should be worded as follows:

An employee is a person who, based on private law, is employed to provide services to another party according to its instructions and integrated in its organisation. Bound by instructions means, according to constraints resulting from the employment contract, the inability of the employed person to make independent entrepreneurial decisions concerning the nature, time and place of work. Circumstantial evidence for the lack of independent entrepreneurial decisions is the fact that the employed person is in a contractual relationship with only one entity and cannot hire their own staff or make their own decisions about how work is organised (Wank 2008, 191).

If one distinguishes employees from self-employed persons, one must also consider pseudo-employees (Wank 2017b, 321 ff.; regarding EU law, Pottschmidt 2006). If you look at the legal systems of a number of countries, you will see that most of them do not recognise the special category of pseudo-employee. In order to provide legal coverage for this group of persons, some either expand the term “employee” (“employees in the sense of the law are also…”) or choose a description that fits pseudo-employees without using this term.

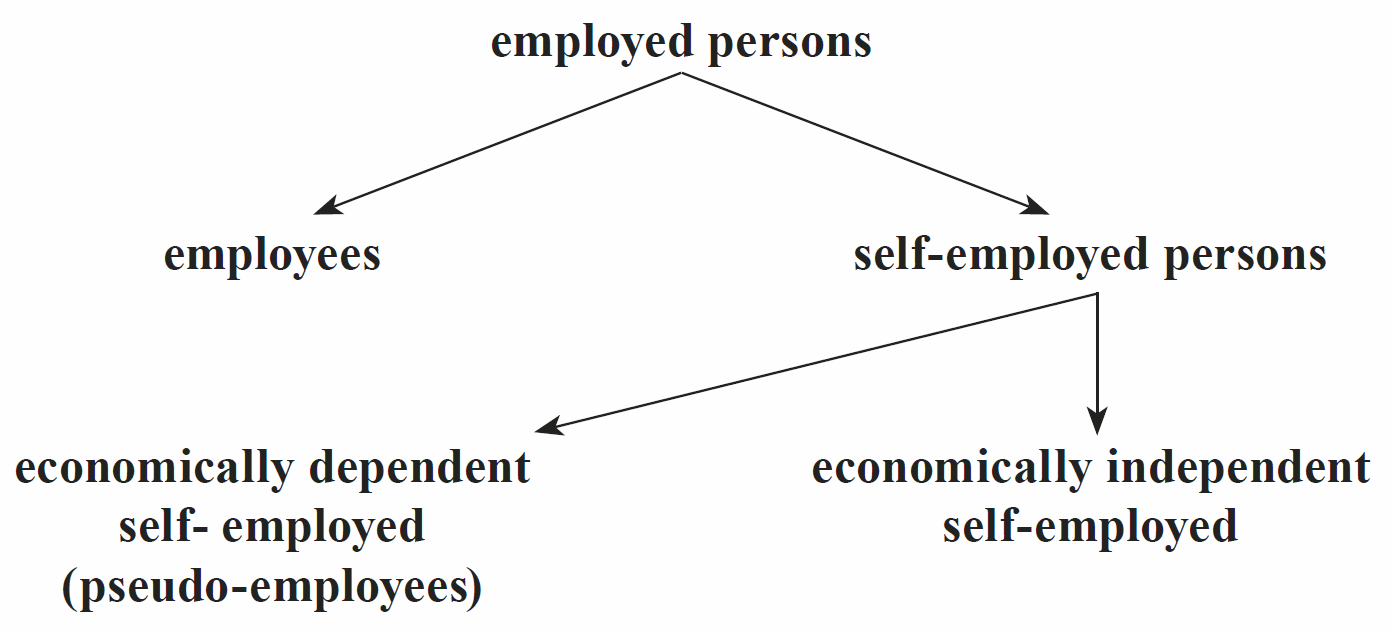

Pseudo-employees can be classified in two ways. One way is to distinguish three types of employees, namely employees, pseudo-employees and self-employed.[32] The BAG and some German authors take this as a basis, but usually contradict each other because their concrete statements are based on the second, accurate classification, which is mentioned below. In fact, there are only two groups of employees, namely employees and self-employed persons (Wank, 2019, § 12 a TVG, para. 7 f.). The self-employed are then subdivided into two sub-groups: “economically independent self-employed” and “economically dependent self-employed or pseudo-employees”.

There is no general legal definition of a “pseudo-employee” (Neuvians 2002, 49 ff.). The legal definition in sec. 12 a TVG is decisive for collective bargaining law, but cannot be generalised (Wank 2019, § 12 a TVG, para. 69 ff.). Apart from that, there are some laws that not only refer to the employee, but to pseudo-employee status.[34] If we accept that employment law protects employees, then the scope of protection provided by these provisions is small (Däubler 2014, 81, 84).

The characteristic feature of a pseudo-employee is economic dependence in all the laws that are related to this term. This results in particular from the fact that such a person works either only or essentially only for one client.[35] Contrary to the opinion of the BAG,[36] this does not depend on the employed individual’s assets, but only on the income from the activity in question (Schneider 2018, § 21, para. 10; Wank 1988, 134 ff., 241).

From the point of view of legal policy, the question arises as to whether the need for special protection is an additional prerequisite: income below a certain income level or attaining most of one’s total income from the special service (Bayreuther 2018, 49, 54 ff.). Furthermore, we must also ask whether that protection should apply only to solo self-employed persons or to all pseudo-employees (Bayreuther 2018, 49, 58 ff.).

The second characteristic mentioned in sec. 12 a TVG, which is also often used elsewhere, the “need for social protection”, is meaningless and should be replaced by other characteristics and indications which are typical for employee status (Schneider 2018, § 21, para. 12). On the other hand, the absence of entrepreneurial opportunities is as decisive as in the case of employees.[37]

Within the group of self-employed persons, a distinction is often made between solo self-employed persons and other self-employed persons (e.g. Bayreuther 2018, 50 ff., 58 f.; Deinert 2015; Fischels 2019b, 208; Uffmann 2019, 360; Wutte 2019, 180). Solo self-employed is not a legal category (Uffmann 2019, 360). It may be appropriate for sociological research to highlight this group, though legally speaking, this is doubtful. The mere fact that someone does not employ any staff does not mean that this person is in need of protection as a self-employed person. Perhaps they operate on the market without a permanent establishment or employees. Similarly to employees, however, only those who are economically dependent in a way comparable to an employee are in need of protection. This manifests above all in dependence on only one contractual or only a few contractual partners (Deinert 2015, para. 11). It would therefore make sense for the law to concentrate on those who are similar to employees.

Only 10.5% of solo self-employed have only one client, while 69.7% have between two and nine clients. Economic dependence, in the sense that the employee receives more than 75% of their income from this activity, is only the case of 8.54% of the solo- self-employed (Uffmann 2019, 360). However, the legal situation lags behind the current developments. There are different approaches to determining how to adapt the legal situation to new forms of employment,[38] e.g. by expanding home worker law (Deinert 2018, 359 ff.; Preis 2017, 173 ff.; Preis 2018, 817, 825), broadening the concept of employee (Bayreuther 2015, 18 ff.) or the concept of pseudo-employee (Bayreuther 2015, 25 ff.).

There are alternative forms of employment to self-employment, including:

An ice cream parlour, swimming area or ski school are only open during a certain season. The operator may conclude a framework agreement with employees as a permanent contract of employment and limit the assignments to the season in question.[41] If an employer does not wish to conclude an employment contract of indefinite duration with immediate effect, they may also simply lay down the conditions for future contracts in a framework agreement. During the season, a fixed-term contract is then concluded under these conditions.

Short-term employment is also possible in the form of fixed-term contracts. Here, however, the case-law of the CJEU[42] and the BAG[43] on abuse of rights must be observed, especially if the job is permanent. Finally, it is also possible to establish on-call work in the employment contract (sec. 12 TzBfG). An unlimited employment contract involves the assignment of work according to the employer’s needs.

All of the above-mentioned forms of employment create a different legal relationship than the one that exists with a pseudo-employee. Individuals engaged on the basis of these forms are employees, whereas the pseudo-employee is self-employed.

While the law applying to home workers enjoyed only a shadowy existence for a long time, the discussion has been reinvigorated, especially following a recent BAG ruling.[44] According to this ruling, the law also covers qualified salaried employment based on the legal definition of a home worker in the Federal Act on work at home (HAG). Some labour law provisions are applicable to this category of work contractors, such as sec. 5, subsection 1, sentence 2, ArbGG, sec. 12 BUrlG and sec. 10 EFZG. A decisive role is played by remuneration security, according to sec. 17–22 of the Federal Act on work at home. It is true that collective agreements can be concluded, but in practice this does not happen. Instead, there is a remuneration regulation by the homework committee (sec. 19 HAG). However, this regulation cannot be generalised in view of the very different types of homework (Bayreuther 2015, 23 ff; opposite: Krause 2016, B 106; Däubler, Heuschmid 2016, § 1 TVG, para. 832).

For both the self-employed (Uffmann 2019, 360, 362) and employees, there are cases where someone works only with one other person, and others where the employee is in direct contact with the client (Dietrich, Patzina 2017, 122 ff.; Wank 2017b, 335 ff.). Depending on this, these situations create particular problems with demarcation (Bayreuther 2015, 59 f.; Kunz 2020, § 4 Solo-Selbständige, para. 87 ff.).

Basically, a good legal definition must be able to cover the most diverse professions in the same way. In this respect, sec. 611 a, subsection 1, sentence 4 BGB refers to the “peculiarity of the respective activity”, even if this is legally unsuccessful. In contrast, the BAG has in some judgements given the impression that there are different concepts of an employee depending on the sector, which differ from the general concept of employee. This approach is unacceptable (Preis 2021, § 611 a BGB, para. 63; Wank 2017b, 393). In the case of educational professions, for example, the BAG bases its judgements on criteria that cannot be justified teleologically (Preis 2021, § 611 a BGB, para. 88; Wank 2006, 5 ff; Wank 2017b, 373).

In some cases, employee status is doubtful because the employee is simultaneously covered by another area of law. This is the case, for example, with persons whose legal relationship is simultaneously governed by labour and company law.

A workable legal definition should not only cover existing cases but also new groups of employees, in particular crowdwork.[45] The platform can act either as a mere mediator or as a contractual partner of the crowdworker (Fuhlrott, Oltmanns 2020, 958, 959; Uffmann 2019, 360, 362; Wank 2017b, 354 ff.). The employee status of the crowdworker is usually negated.[46] Discussion is also underway on the subject of whether crowdworkers who only work for one platform and derive their livelihood from it are pseudo-employees (Burazeri 2019, 289, 291; Däubler, Klebe 2015, 103; Schubert 2018, 200, 204; Husemann, Wietfeld 2015, 27, 44) or also home workers (Fitting 2020, § 5 BetrVG, para. 311). Special regulations in civil law are also considered (Klebe 2016, 277, 279; Wank 2017b, 357). Finally, protection can also be achieved under collective law (Bayreuther 2015, 66 ff.). Meanwhile, the BAG ruled that crowdworkers may be employees.[47] The Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (BMAS) presented the paper “Faire Arbeit in der Plattformökonomie” with proposals for more protection for those working via online platforms on 27 November 2020.

As explained above, a distinction must be made between protection with regard to the drafting of contracts, i.e. with regard to commercial and civil law, on the one hand, and protection similar to that under labour and social security law on the other. In this second respect, it is a matter of protecting the employee against occupational and adverse life events.[48]

In terms of individual labour law, occupational health and safety, as a special area of labour law, is of primary importance. This concerns health and safety at work. It is not surprising that some of the relevant provisions of labour law are also applicable to self-employed persons, in particular to pseudo-employees. Thus, with regard to sec. 618 BGB, it makes no difference whether an employee has an accident at home because of a defective staircase or a solo self-employed painter employed to provide services.

Labour protection law also includes working time law and holiday law. In this respect, employees are protected, but self-employed persons are not, even if they only work for one client. In such a situation, the relevant rights can only be granted to them under a civil law contract. In anti-discrimination law, too, pseudo-employee rights must be included (Wank 2009, 1049 ff.).

Another area concerns the so-called “sozialer Arbeitsschutz” (personal group-related social work protection), i.e. the protection of special groups of persons, such as maternity protection and, due to the uncertain legal situation, the protection of a single parent. In this respect, too, there is a lack of protection for the self-employed.

Of particular importance is the protection of self-employed persons with regard to remuneration (Bayreuther 2015, 28 ff.; Bayreuther 2020, 99, 100 ff.). Under German law, it is impossible to set a minimum wage in the same way as for employees (Bayreuther 2015, 35 ff.). In particular, the expenses would then also have to be taken into account (Bayreuther 2015, 37). At best, a claim to appropriate remuneration could be considered, cf. sec. 89 b, 90 a HGB, sec. 32 UrhG (Bayreuther 2015, 38 ff.), or fees tailored to the profession in question, such as for architects (Bayreuther 2015, 42 ff.). A clause that leaves it up to the client to decide whether to accept the service would also have to be eliminated from business transactions (Wank 2017b, 358; opposite Bayreuther 2015, 47).

The law of termination contains only notice periods for the self-employed (sec. 621 BGB, sec. 649 BGB), but no requirements as to content. Legal protection would only be conceivable for the solo self-employed (Bayreuther 2015, 46 ff.).

Contrary to widespread arguments in Germany advocating for a narrow definition of an employee, the classification of an employee as a pseudo-employee does not mean a significantly higher level of protection (Bayreuther 2015, 25 ff.; Wank 1988, 235 ff., 243 ff.).

Even though the Federal Act on work at home has now been extended to cover office work, a permanent business relationship is required for a home work relationship (Bayreuther 2015, 20). Incidentally, the homework committee model cannot be generalised (Bayreuther 2015, 21 ff.).

Protection of the self-employed can be achieved not only through individual labour law but also through collective labour law. Such protection is not foreseen by the works constitution law. Although the Works Constitution Act does not only cover employees of the enterprise, but also temporary workers who have an employment relationship with the employment agency (Linsenmaier, Kiel 2014, 135; Wank 2021, § 14, para. 2 ff.), it does not cover self-employed persons with the exception of home workers who work only for one enterprise (sec. 5, para. 1, sentence 2 BetrVG).

The situation is different in collective labour law, in the area of collective bargaining law. In essence, collective bargaining law is the law which grants power to employees who are not powerful enough as individuals, but together have the possibility of industrial action. According to the constitution, as well as case-law and literature, there is generally no comparable right for self-employed persons. However, the situation is different in the case of pseudo-employee rights because sec. 12 a TVG gives them the opportunity to form associations and conclude collective agreements.[49] This also leads to freedom of industrial action, which does not violate cartel law (Bayreuther 2015, 88 ff.; Bayreuther 2019, 4 ff.). In addition, other forms of collective agreements are also being considered for the self-employed (Bayreuther 2015, 72 ff., 77 ff.).

In addition to protection under private law, Germany also offers protection under social security law. This covers certain adverse life events, namely: disease, the need for care, maternity, age and unemployment. Since labour law makes a sharp distinction between employees and self-employed persons and since social security law is fundamentally linked to employee status (see sec. 7, para. 1 SGB IV), coverage of these risks by social security law for self-employed persons would be ruled out. However, there are exceptions in German social security law (Deinert 2015, para. 131 ff.).

Only the groups listed in sec. 2, sentence 1 of the German Social Code Book VI (SGB VI), such as self-employed teachers, artists, etc., are subject to compulsory pension insurance. The duty of provision of this benefit exists with regard to illness and healthcare, but only for farmers, artists and journalists (sec. 5, para 1, no. 3 and 4 of SGB V; sec. 20, para 1, sentence 2, no. 3 and 4 of SGB XI). Other self-employed can take out voluntary insurance (sec. 9 SGB V; sec. 26, para 1, sentence 1 SGB XI). Only farmers, etc. are insured against accidents at work and occupational diseases (sec. 2, para 1, no. 5 a, 6, 7, 9 SGB VII). Coverage under unemployment insurance is possible by application (sec. 28 a., para 1, sentence 1, no. 2 SGB III).

As far as the need for protection of pseudo-employee or solo self-employed persons is concerned, in reality completely different groups can be identified. Uffmann distinguishes between “precarious”, “pragmatics” and “professionals” (Uffmann 2019, 360, 361). Professionals can earn twice as much as the standard wage, have sufficient financial reserves and adequate retirement security.

Since self-employed persons generally bear the full burden of social security contributions, they are often overburdened, especially in the start-up phase (Leonhardt 2020b, 207 f.). The COVID-19 epidemic shows that a social security system for the self-employed is necessary.

With regard to the protection of economically dependent self-employed persons, the focus should be on pseudo-employees rather than on solo self-employed persons. Several areas of protection must be distinguished:

a) In individual labour law, the first area includes safe working conditions and anti-discrimination provisions, which are also to be extended to employees.

b) The second area can also include special issues related to pseudo-employees, such as: working hours, holiday, protection of special groups, protection of remuneration, protection against dismissal. Protection under labour law must be accompanied by protection under social security law. Access to the labour courts should also be open, see sec. 5 ArbGG. In collective labour law, pseudo-employees must have the opportunity to establish a counterweight to a powerful market counterparty.

c) In the third area, special regulations can be created for certain forms of activity.

Labour law is predominantly part of civil law. The self-employed individual is therefore dependent on law enforcement under civil law and civil procedural law. However, control is also partly incumbent on administrative authorities, e.g. through supervisory authorities for health and safety law and agency work (“Gewerbeaufsichtsämter”). Some regulations are reinforced by criminal law.

The German government has presented a White Paper with regard to planned reforms.[50] According to this paper, self-employed persons should be covered by statutory pension insurance.[51] The income situation should be improved by encouraging the conclusion of collective agreements (Kunz 2020, § 4 Solo-Selbständige, para. 7). There are corresponding passages in the coalition agreement of 2018.[52] Some of the plans were implemented by the “Act on the Reduction of Contributions to the Statutory Pension Insurance Scheme”.[53] On 27 November 2020, the BMAS presented the paper “Faire Arbeitsbedingungen in der Plattformökonomie”, proposing that platform workers should be included in the social security system and regulation providing a less complicated way of controlling their contracts. In the literature, comprehensive proposals for the protection of economically dependent self-employed persons have been presented (Bayreuther 2015; Deinert 2015).

In the social security system, de lege ferenda, the involvement of clients similar to that of the social security contribution for artists (sec. 23 ff. KSVG) is taken into consideration. In contrast, state subsidies, as in Austria, would be a better solution (Leonhardt 2020b, 207, 209 f.).

Given the discrepancy between the term and the actual situation, a distinction must be made between two cases, sham business and sham self-employment. The case of fictitious transactions concerns situations where the parties agree that an employment relationship exists, although in reality a self-employed activity is being carried out, usually due to advantages with respect to social security, taxes or bankruptcy.[54] In the case of bogus self-employment (or sham self-employment), on the other hand, the client is unilaterally interested in employing the other person as a self-employed person, while in reality there is an employment relationship. We will only address the latter case. The extent to which bogus self-employment exists depends on legal and economic conditions.

In order to be able to determine the difference between employees who are clearly qualified as employees and other employees who are wrongly referred to as self-employed (“bogus self-employed”) (Boemke 1998, 258 ff.; Hromadka 1997, 569 ff.; Wank 1992, 90 ff.), a factually correct and practicable definition of an employee is needed. This is lacking in Germany, Austria and most other countries (Wank 2019, 131). The existing definitions are often meaningless; cf. the definition of the European Court of Justice, which states that an employee is someone who works. The existing definitions are in need of legislative improvement, as the example of sec. 611 a BGB has shown (see above 3.2.).

Most of the definitions in legislation, case-law and doctrine have not succeeded in this respect because they do not take into account the difference between characteristics, sub-characteristics and circumstantial evidence (indicators) (Wank 2017b, 253 ff.), as well as by virtue of the fact that they do not provide operational characteristics in the form of indicators.[55] They do not mention or explain the tertium comparationis, i.e. the actual difference between employees and self-employed. The real characteristic is the impossibility of making independent entrepreneurial decisions. As long as this aspect is missing in the definition, the definition is arbitrary, since it does not grasp the real problem (see the proposal for a definition above 3.8.).

Awarding benefits to self-employed persons rather than employees is usually more advantageous for entrepreneurs for several reasons, so entrepreneurs take advantage of this solution, even if they were considering hiring employees.[56]

It is not easy to determine how many bogus self-employed people there are in Germany. There are legal reasons for this, as well as reasons based on empirical social research.

The objective set for the legislature with regard to the Act amending the AÜG, namely to reduce the legal uncertainty that exists in the face of case-law that makes everything dependent on the circumstances of the individual case,[57] cannot be achieved by copying the guiding principles of this case-law literally. As has been shown (see 3. above), undefined legal terms are used without subordinate characteristics, and the relationship between the different characteristics is unclear.

Greater legal certainty can be achieved through sub-characteristics (e.g. integration = recourse to personnel of the contractual partner, recourse to material of the contractual partner, organisational integration, control), as well as through operational criteria which are used as indicators (e.g. own business premises, own customer base, etc.). Corresponding attempts to amend sec. 7 SGB IV on the basis of a commission proposal,[58] as well as the speaker’s draft of sec. 611 a BGB,[59] have failed because the character of circumstantial evidence has been misjudged in case-law, literature and practice.[60] Nor is it sensible in the case of circumstantial evidence to work with a presumption (e.g. three out of five indicators), if no distinction is made between evidence based on factual constraints and selected indicators.

In addition to the legal problems, there are problems of empirical social research. For example, the data collected are based on self-reporting, which is not always accurate and sometimes either consciously or unconsciously inaccurate.

Finally, the translation of legal criteria into empirical criteria is a problem. If the BAG refuses to provide a clear definition, a questionnaire, with a benevolent interpretation, must translate statements of jurisprudence into operational characteristics.

When working with undefined legal terms, the formulations on which a questionnaire is based vary according to the legal model. For example, in 2017, an empirical study distinguishing between a BAG model, a BAG-Plus model and an alternative model produced the following figures:[61]

With a figure of 1,107,471 main employees in the grey area between self-employed and employees (Dietrich, Patzina 2017, 84, 151):

The number of employees is correspondingly lower under the BAG model than under the alternative model.

As with all statistics on facts, everything depends on whether the facts are collected correctly, i.e. whether the rules of empirical social research are observed. This is the case in Germany. Two empirical studies commissioned by the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs have examined the question in detail and provided the appropriate answers (Dietrich 1996).[62]

A completely different question is whether cases of bogus self-employment are clarified in practice. This depends on whether employees with an unclear legal status file a complaint and whether an official inspection is carried out. It is rarely advisable to take legal action in Germany, as both the case-law and the new sec. 611 a BGB, which was created on the basis of the case-law, offer barely any legal certainty. However, at least in social security law, there is the possibility of a status determination procedure (under sec. 7a SGB IV).

It is the responsibility of tax authorities and social insurance institutions to verify whether the regulations are being observed with regard to employees. Supervision is typically carried out within the scope of a tax audit. However, given the staffing levels in German administration, the probability of a company being audited is low.

Reversing the inaccurate classification of an individual as a self-employed person leads to numerous problems.[63]

The data for Austria concerning self-employment can be found in “Selbständige Erwerbstätigkeit, Modul der Arbeitskräfteerhebung 2017”, ed. by Statistik Austria in 2018. The survey included all persons older than 15 years with a job. The survey included sociodemographic and labour market statistics (Wiedenhofer-Galik 2018, 31 f.).

In 2017, on average, 4.261 million persons were employed: 87.6% of them, i.e. 3.733 million, were employees, 10.9% (i.e. 465,000) were self-employed and 1.5% (62.300) were family workers. Among 10.1% self-employed, 6.3% had no employees, and 4.7% had employees. Most self-employed were men. In contrast to men, self-employed women tended to work alone (5.5%) and not with employees (2.6%). Self-employed persons started their current job later than employees, and worked longer hours. They were, on average, older than employees.

Predominantly, this professional activity takes place in the service sector (67.9%). One fifth work in agriculture and forestry. 13% of the self-employed work in the industry sector, especially those with employees. The main motive for becoming self-employed is to continue the family business (25.3%), especially in the agriculture sector (82.1%) (Wiedenhofer-Galik 2018, 21, 39 ff.). Other motives were to have more autonomy (22.9%) or to take advantage of a good opportunity (18.4%). Barriers to self-employment were mostly financial (53.2%) (Wiedenhofer-Galik 2018, 44 ff.)

In Austria, too, a distinction can be made between self-employed persons in general and solo self-employed persons (cf. Germany 4.3). If iPros (cf. Germany 1.4) bb) are also considered as a special group, one can fall back on corresponding data (Leighton, Brown 2013, 7, 73, 76, 78, 86, 88, 90).

Employees also enjoy protection under social security law in Austria. In sec. 2 of the General Social Security Act, an employee is defined as a person who, for remuneration, is employed in a legal relationship with personal and economic dependence. However, unlike in Germany, the distinction between employed and self-employed persons is not so important in Austria, because all self-employed persons are also subject to social security protection.

For Union law, refer to the comments on Germany (cf. Part Germany 2.1.).

Insofar as legislative competence in labour law is not expressly assigned to the Federation, it lies with the “Länder” (Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 3).

In ordinary law, the employment contract (for self-employed persons and employees) is regulated in civil law under section 1151, para. 1 of the Civil Code.

Employees also enjoy protection under social security law in Austria. In section 2 of the General Social Security Act, an employee is defined as a person who, for remuneration, is employed in a legal relationship of personal and economic dependence. However, unlike in Germany, the distinction between employed and self-employed persons is not so important in Austria, because all self-employed persons are also subject to social security obligations. However, the self-employed are compulsorily insured with the Sozialversicherungsanstalt der Gewerblichen Wirtschaft (SVA), while employees are insured with the Gebietskrankenkasse (GKK; now the Austrian Health Insurance Fund). The respective GKK decides in which category an employed person is to be classified.

The Austrian Constitution contains no specific provisions on the demarcation between employed and self-employed persons (Pelzmann 2011, 1 ff., para. 9).

Austrian individual labour law is very similar to German law. This applies in particular to the concept of employee. Therefore, German case-law and literature can always be consulted for further information. Critical voices on the characteristic “personally dependent” are unknown in Austria.

In ordinary law there is no legal definition of employee and, consequently, of a self-employed person. In Austria there is – as before sec. 611 a BGB came into force in Germany – only one legal definition of the person performing a contract of service, found in § 1151, para. 1 ABGB (Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 11). According to this definition, a person performing a contract of service is someone who offers services to another person for a certain period of time. Case-law and literature agree that this definition includes both self-employed and employees. This is based on the same systematic error as German law: the correct opposing concept to an employee is not (only) the self-employed offering a service through a contract of service, but every independent self-employed person who provides services for another person (cf. Part I Germany 3.2.1.).

Personal dependence (as a generic term) is characteristic of the employee.[64] It is also referred to as a subordination relationship (Löschnigg 2017, 4/009; see also Preis 2020, § 611 a BGB, para. 18 referring to the CJEU; Wank 2017c, 3 ff.). Austrian courts refer to the concept of employee as a typus concept (cf. Part I Germany 3.2.7.). It is primarily concerned with binding instructions, related to working time (Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 84 ff.; Risak, Rebhahn 2017, 1, 4), place (Löschnigg, 2017, 4/004; Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 78 ff.) and work-related behaviour (Löschnigg, 2017, 4/004; Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 35; Tomandl 1971, 68). Austrian law also recognises an “employee not bound by instructions”, who is nevertheless an employee because they are subject to the “silent authority of the employer” (Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 36) (cf. Part I Germany 3.2.3.).

According to sec. 1153 ABGB, the employee must perform their work in person, but a deviating agreement is permissible.[65] In addition to the obligation to follow instructions, the definition of the employee depends on integration, namely organisational integration. This also includes supervision by the employer (Risak, Rebhahn 2017, 1, 10). In addition to the above-mentioned characteristics, the courts also consider circumstantial evidence. This includes, for example, that the contractual partner must provide the work material. Periodic cash payments instead of payment for a work result are also typical for employees (Risak, Rebhahn 2017, 1, 11 ff.).

The fact that an entrepreneurial risk is borne is taken into account in particular when distinguishing between employees and contractors. The criterion of economic dependence is only used as an alternative (Löschnigg 2017, 4/006; Marhold, Friedrich 2017, 36). It is expressly mentioned in sec. 4, para. 1 BEinstG. In contrast to German case-law and literature, which largely ignore this criterion,[66] Austria emphasises that the employee does not act on their own behalf.[67]

The literature erroneously considers all criteria as mere circumstantial evidence (Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 35), whereby no distinction is made between characteristics which must be present and circumstantial evidence which may be present in individual cases. With regard to the characteristics, an overall weighing up is important (cf. Part I Germany 3.2.5.) (Löschnigg 2017, 4/012; Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 35; Tomandl 1971, 74 f.). The actual implementation is decisive (Löschnigg 2017, 4/010; Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 38).

The contract of employment must not only be differentiated from the contract of service (Löschnigg 2017, 4/015; Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 40 ff.), but also from the contract for work and services (Löschnigg 2017, 4/015; Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 39 f.). A distinction is also necessary in relation to cooperation under a partnership agreement (Löschnigg 2017, 4/038; Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 42 ff., 44 f.). External managers of a limited company (GmbH) are employees (Pelzmann 2011, 1 ff., para. 27).

In addition, there are different concepts of employee for special areas of law, e.g. sec. 1, para. 2, no. 8 AZG and sec. 36, para. 2, no. 3 ArbVG (Löschnigg 2017, 4/054 ff.) have their own concept of employee (Löschnigg 2017, 4/081 ff.; Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 46; Risak, Rebhahn 2017, 1, 5). In sec. 4, para. 2 of the General Act on Social Insurance, the employee is defined as a person employed for remuneration who is personally and economically dependent. In practice, the term does not differ from the definition of “employee” used in labour law (Risak, Rebhahn 2017, 1, 4). The tax law definition of employee also corresponds to that of labour law (Risak, Rebhahn 2017, 1, 4).

A large number of laws also expressly apply to pseudo-employees (cf. Part I Germany 4. a). The definition corresponds to the one used in German law: pseudo-employees are not personally or economically dependent (Löschnigg 2017, 4/147 ff.; Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 37, 53 f.; Wachter 1980, 29 ff., 103 ff.). They are considered to be in need of social protection (Wachter 1980, 75 ff.). According to sec. 51, para. 3, no. 2 ASGG, for example, pseudo-employees are treated equal to employees in the context of procedural law (Löschnigg 2017, 4/148; Pelzmann 2011, 1 ff., para. 24). Some other labour laws, concerning agency work, employee liability and anti-discrimination, are also applicable to pseudo-employees (Löschnigg 2017, 4/148; Risak, Rebhahn 2017, 1, 20). Economic dependence is understood first and foremost as activity on behalf of only one or a limited number of clients. The absence of a permanent establishment and the long duration of employment are also mentioned in case-law (Löschnigg 2017, 4/152; Wachter 1980, 40 f.). Social security law and tax assessment are of no significance (Wachter 1980, 47 ff., 173 ff.). Wachter argues strongly in favour of a typus (Wachter 1980, 109 ff.).

Home workers are not employees (Löschnigg 2017, 4/154 ff.; Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 37 f.), but governed by the law on home work (Risak, Rebhan 2017, 1, 21). Furthermore, civil servants (Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 34; Risak, Rebhahn 2017, 1, 3), persons in family employment (Löschnigg 2017, 4/042; Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 45; Risak, Rebhahn 2017, 1, 3) and prisoners (Löschnigg 2017, 4/057; Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 34) are not employees.

There is competition between various fields of law, especially with regard to company law (Löschnigg 2017, 4/037; as regards members of the board 4/165 ff.; Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 42 f.).

The literature on the concept of employee and thus implicitly on the self-employed is essentially in line with case-law. In the literature, too, personal dependence is regarded as decisive (E.g. Löschnigg 2017, 4/004). The literature also sees the employee as a typus (Risak, Rebhahn 2017, 1, 9).

Integration is regarded as a sub-term of binding instruction (Risak, Rebhahn 2017, 9 f.) or personal dependence (Löschnigg 2017, 4/004), part of which is control (Löschnigg 2017, 4/005; Risak, Rebhahn 2017, 1, 10 f.). The literature also regards the “silent authority of the employer” as sufficient (Löschnigg 2017, 4/004; Risak, Rebhahn 2017, 1, 10 f.). According to sec. 1153 of the Civil Code, the party must render the service in person, but this is not mandatory (Risak, Rebhahn 2017, 1, 11).

In addition to the characteristic “personally dependent”, the literature also mentions circumstantial evidence (Risak, Rebhahn 2017, 1, 12 f.). In some cases, a lack of registration with the social security system and payment of income tax are incorrectly used as criteria, although these criteria only say something about the parties’ assessment (restrictive: Löschnigg 2017, 4/011).

In summary, Austrian literature does not differentiate sufficiently between characteristics, sub-characteristics and circumstantial evidence, i.e. between binding instructions and integration as characteristics, instructions concerning content, place and time of the activity and integration into the client’s organisation with regard to planning, personnel and tools as sub-characteristics, or indications such as: Does the employee have only one client? Are they allowed to employ staff (e.g. Löschnigg 2017, 4/013)?

A separate approach is taken by Tomandl, which makes a distinction according to legal sphere (Tomandl 1971).

Austrian law recognises the special category of the pseudo-employee (Wachter 1980; see 4 Part One a). In contrast, the category of solo self-employed does not exist legally here either (cf. Part I Germany 4.2.). New forms of contract, such as crowdwork, are not specifically regulated. Framework agreements which contain pre-agreed working conditions are possible.[68] As in Germany, the legal consequences of a pseudo-employee classification are limited.

A whole series of laws apply only to employees; in individual labour law these include, among others (Marhold, Friedrich 2012, 40 ff.), regulations on: